Dark Tourism and Destination Branding: The Case Study of Auschwitz Concentration Camp

July 9, 2022

Public Perspectives of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): Factors Influencing Identification and the Difference in Perspectives When IPV is Committed In-Person In Comparison to Via Technology

July 10, 2022Embarking on a sensory odyssey, a spa transcends the realms of relaxation, becoming a tapestry of memorable experiences woven with the threads of tranquillity, rejuvenation, and a symphony of indulgent sensations.

Outline

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Data Collection Methods

- Findings

- Analysis and Discussion

- Conclusion

- References

- Appendices

In today's fast world, people want special moments, especially those looking for peace and refreshment. Spas are a great way to create lasting experiences. This blog dives into the idea of memorable moments and how they connect with spas. We'll look at the details that make a spa visit great and find out why these moments stick with us even after we leave.

Discover the Essence of Creating Memorable Spa Experiences in this Blog

In the search for amazing experiences, spas become a special place for creating unforgettable moments. This blog explores the core of this idea, breaking down the small details that make a spa visit memorable. From enjoying the senses to personalized care and delightful surprises, we'll uncover the complex elements that make spa experiences stick in our memory, inviting us to relive these special moments.

Introduction

In 2016, the global health and wellness market boasted a total worth of $686 billion, as reported by Weinswig in 2017. Projections from Euromonitor International in 2019 suggest that by 2021, this industry is set to expand to a substantial $815 billion, marked by a steady 3.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR). Additionally, the spa sector is on track to achieve remarkable growth, with estimates from the Global Wellness Institute in 2018 predicting a value of $128 billion by 2022. Key drivers behind this growth include rising disposable incomes, the burgeoning trend of wellness tourism, and increased consumer willingness to invest in their well-being.

From 2015 to 2017, the hotel and resort spa category emerged as the most rapidly expanding segment, according to data from the Global Wellness Institute in 2018. This growth trend is attributed to an increasing consumer interest in wellness-focused travel experiences. Simultaneously, destination spas and health resorts secured the third growth position, boasting 2,633 establishments in 2017 and generating a combined spa revenue of $8.3 million.

Tabacchi (2010) acknowledges that prior research in the spa industry primarily revolves around the growth of various spa typologies, such as day, hotel, resort, and destination. Despite some foundational work in the field, the research landscape remains fragmented, indicating a need for further development. Existing studies predominantly centre on the hospitality and tourism sectors, with contributions from researchers like Bogdan (2013), Brunner-Sperdin et al. (2012), Koskinen and Wilska (2019), Rojas and Camarero (2007), and Sirakaya et al. (2004). However, the spa industry has yet to comprehensively explore how memorable experiences are crafted and whether customer loyalty impacts the satisfaction derived from past experiences. While a substantial body of research delves into spa-goers' motivations, as demonstrated by works from Lo et al. (2015), Loureiro et al. (2013), and Mak et al. (2009), there are notable gaps in our understanding of customer loyalty, guest satisfaction, and the formation of memorable spa experiences.

The primary objective of this study is to expand the existing knowledge base within the spa industry. It aims to provide valuable insights that can enhance guest loyalty and the creative design of innovative spa experiences.

Aim

This study explores the concept of memorable spa experiences as it applies to the spa.

Objectives

Explore the motivations of spa consumers

Critically analyse how the senses impact the spa experience

Critically evaluate how memorable spa experiences create client retention

Justify what part of the spa experience creates consumer loyalty

Significance of Study

Prior research indicates that when engaging with service industries, consumers purchase experiences and memories, contrasting with purely utilitarian and standardized services and quality (Buxton, 2018; Sipe and Testa, 2018). Moreover, Lo et al. (2015) suggest the importance of investigating variations in service quality dimensions and emotions in the context of hotel and resort spa customers with diverse purposes and motivations for their spa visits.

Hu et al. (2019) propose that recurring patronage is typically associated with returning visits and customer loyalty. It reflects customer satisfaction, with prior experiences exceeding guest expectations and resulting in positive overall experiences (Um, Chon, and Ro, 2006). East et al. (2006) concur with this perspective, asserting that personal recommendations stem from high satisfaction levels.

Literature Review

A literature review is a scholarly journey through the landscape of existing research, illuminating the path for discoveries and insights. It's the insightful analysis of the past that paves the way for the future of knowledge.

Typology of SPA

Spas, as sanctuaries for the rejuvenation of mind, body, and spirit, are dedicated to the personal well-being of their patrons (International Spa Association [ISPA], 2011). However, not all spas offer identical experiences. The International Spa Association (ISPA, 2017) has identified seven distinct typologies of spas, including club, day, hotel/resort, destination, medical, mineral springs, and cruise ship spas. Yet, Ahani et al. (2019) propose a novel approach that segments the spa market using social media and TripAdvisor reviews, harnessing statistical ratings and independent textual reviews to shape expectations and gather valuable data, aiding spa-goers in choosing the spa type that aligns with their preferences.

Destination spas, characterized by extended stays spanning 3-4 days, often featuring weeklong packages, offer an immersive experience. In contrast, day spas provide treatments and spa facilities for a single day without overnight accommodations. These establishments strongly emphasise rejuvenation, relaxation, and revitalization, offering a diverse range of treatments, facilities, nutritional options, exercise, and meditation. Research by Adongo et al. (2017) suggests that guests at destination spas actively engage in various wellness and physical activities, given their longer stays. The primary objective for overnight visitors to destination spas is to foster healthy living habits during their stay, a commitment that ideally extends beyond their visit, promoting lasting well-being (Dimitrovski and Todorović, 2015). This underscores the rationale for undertaking research specifically focused on destination spas, considering the extended duration of guests' interactions with the environment and their increased exposure to health and well-being services during their stay, with the ultimate goal of promoting wellness and longevity.

The choice of a spa experience may hinge on the spa's ability to meet the expectations and desires of consumers (Good Spa Guide, 2014). Consequently, consumers select a particular spa based on its services and offerings, ultimately opting to invest their discretionary income accordingly.

SPA Experience

Spa consumers have transformed, as noted by Hu et al. (2019). They now possess the ability to select a specific spa based on its value and quality. These consumers have evolved into a discerning and well-informed group, adept at conducting research, making online reservations, and enjoying increased accessibility to diverse spas and activities that contribute to their overall health and well-being.

As affirmed by Hu et al. (2019), the "service" element significantly influences overall satisfaction (OS) and serves as a moderator of OS, impacting repeat patronage and directly influencing customer return visits. In today's society, spa consumers are evolving into discerning and knowledgeable customers, educating themselves through various channels such as the Internet, word-of-mouth, and social media platforms (Mandelbaum and Lerner, 2008). This heightened awareness has elevated expectations for spa environments and experiences, with a demand for high standards and a diverse range of products and services to cater to various consumers. The likelihood of repeat patronage and loyalty is contingent on the overall satisfaction (OS) derived from the spa experience (Liu et al., 2017). Disappointment in the experience may result in concessions, complaints, and, ultimately, the loss of repeat business. However, as Sethna and Blythe (2019) found, guest satisfaction does not always guarantee loyalty.

The spa experience is depicted as a vital psychological activity (Lo, Wu, and Tsai, 2015; Goldstein, 2015; Csikszentmihalyi, 1992). Each spa guest brings their preferences, influenced by emotional or physical motivations, which drive their desire for spa consumption. On the other hand, Spa therapy is geared towards health promotion, prevention, therapy, and rehabilitation (Gutenbrunner et al., 2010).

According to a survey conducted by the Statista Research Department 2018, spa consumers have a variety of reasons for seeking spa treatments, ranging from medical needs and pain relief to relaxation, stress reduction, and the desire for indulgence and pampering. Recent research presented by Champalimaud and O'Connell (2019) at the Spa Life conference highlights that "79% of spa customers consider it important to leave their spa experience feeling mentally relaxed and rejuvenated." This indicates that the average consumer primarily seeks a stress-free experience, with 60% of spa-goers in the UK emphasizing the importance of being able to 'relax and unwind' when visiting a spa.

To ensure the highest customer satisfaction, spas should strive to craft an experience that instils a profound sense of tranquillity. Wuttke and Cohen (2008) extol that immersing consumers in a sensory journey encompassing touch, smell, taste, sound, and sight can be particularly appealing. Engaging these senses throughout the spa experience is paramount, as Bjurstom and Cohen (2008) emphasise. This comprehensive approach should extend from the overall atmosphere and ambience of spa facilities and rooms down to the conduct and attire of their staff.

Consumption Emotion

According to Richins (1997), emotions are consumers' distinct responses during their interactions with products or experiences. These emotions, whether experienced before or after consumption, are called "consumption emotions." Lee and Choi (2011), as cited by Lee et al. (2015), emphasized the significance of consumers' emotional experiences during spa visits, as these emotions can significantly influence overall satisfaction with the experience. Previous research has consistently shown that emotions are crucial in shaping consumer responses (Lo and Wu, 2014).

Furthermore, atmospheric cues within a spa environment have the potential to impact the emotional states of consumers, which, in turn, can either enhance or diminish their levels of satisfaction (Loureiro, Almeida, and Rita, 2013). The level of satisfaction, in turn, can directly impact the number of positive and negative recommendations generated by guests. To achieve favourable outcomes, it is essential for the spa experience to not only meet but also exceed guests' expectations and create an aesthetically appealing environment that leaves a lasting and positive impression rather than merely satisfying their basic needs (Pine and Gilmore, 1998).

Assessing emotions can be demanding and complex, often fraught with the potential for misunderstanding, particularly when attempting to interpret consumers' body language or facial expressions. Izard (1977) highlighted the intricacies of individuals conveying their emotions through facial muscle movements. Consequently, the task involves the ability to accurately identify, differentiate, and discern shifts in emotional states.

Discerning customers' emotional states in spas can be challenging since they may be preoccupied with personal matters, sharing laughter over a friend's joke, or fully immersing themselves in the spa experience without outwardly displaying any emotional expressions.

Consumer Loyalty

According to East et al. (2016), retention refers to the ongoing and repeated purchase of various products, experiences, and services from a specific brand or company over an extended period. It's worth noting that personal recommendations through word-of-mouth and favourable online reviews can attract new customers, as emphasized by East et al. (2006:16).

Sethna and Blythe (2019) argue that establishing loyalty programs to enhance retention is a more effective strategy than focusing solely on attracting new customers. This is primarily because the cost of retaining existing customers is generally lower than the expense of acquiring new ones, as highlighted by East et al. (2016).

In these circumstances, it becomes evident that mere satisfaction is insufficient to foster customer loyalty, as argued by Sethna and Blythe (2019). However, East et al. (2006) concurs with this perspective but adds that personal recommendations stem from the foundation of satisfaction. According to industry studies, emotional value emerges as the primary factor contributing to enhanced customer loyalty, supported by Forrester (2016) and Sipe and Testa (2018).

Reitsamer (2015) emphasizes that without mental re-enactment, the influence on customer loyalty is primarily driven by visual impressions. This underscores the significance of service quality and total quality management (TQM) in shaping consumer judgments and initial impressions of the spa. Furthermore, the article goes on to highlight the importance of sensorimotor experiences in knowledge acquisition and the formation of customer loyalty (Reitsamer, 2015).

Relationship marketing, which emerged in the 1980s, is described as the practice of "attracting, maintaining, and enhancing" customer relationships, as outlined by Berry (1983). This philosophy remains relevant today, with businesses employing marketing strategies such as market research to understand better their target audience (Kumar et al., 2009). Ultimately, this approach fosters loyalty, increasing retention rates and profitability. Storbacka et al. (1994) characterize relationship marketing as a cooperative bond between buyers and sellers instead of a competitive transaction with rivals. Trust is pivotal in these business relationships, fostering a mutual and supportive connection.

Meszaros (2018) recognizes that upselling in the spa context should revolve around fulfilling and gratifying individual desires by providing personalized products and services. Within the spa experience, numerous chances exist for tailoring the experience to guests' specific preferences. This can be exemplified through the provision of customized treatments tailored to meet each guest's individual needs. For instance, offering skincare products that cater to different skin types can provide greater benefits. Likewise, presenting guests with various dietary options, such as vegetarian and vegan choices for afternoon tea or meals, can further enhance their satisfaction.

Memorabilia

Pine and Gilmore (1998) assert that "experiences represent a unique economic offering," and to craft a memorable experience, businesses must employ cues that actively promote and connect to "create the desired impression." Multisensory, unforgettable experiences have the potential to instigate personal transformation, as noted by Kylänen (2006). When engaging in a commercial experience, the perceived value is intertwined with the actual act, and this can influence the retention of memories, depending on the quality and how deeply the experience is appreciated, as highlighted by Poulsson and Kale (2004).

To delve further into this concept, it is crucial for experiences to captivate customers by introducing a bundle of sensory mementoes that represent and extend the customer's post-experience journey, leaving a lasting imprint, as discussed by Joy and Sherry (2003), cited by Reitsamer (2015). For instance, Comfort Zone (2015) offers clients a scented fabric wristband as a complimentary gift following massage treatments. These wristbands are infused with a few drops of a chosen oil blend, such as Oriental, Mediterranean, Indian, or Arabian, which is selected before the treatment. Providing such personalized elements to clients makes their experience unique, allowing them to carry the memory of their treatment home.

Sipe and Testa (2018) examined two fundamental concepts within hospitality and tourism: service theory and the experience economy. Interestingly, these concepts can also be applied effectively to the spa industry, which is known for providing distinctive experiences rather than standard services. Their research revealed that the most prominent elements associated with memorable experiences in this context were aesthetics and escapism, which received significantly high and positive ratings.

Moreover, Bodeker and Cohen (2008) describe spas as sanctuaries for rejuvenation and relaxation, where personal transformation is possible, and individuals can experience a profound connection with their true selves and purpose. It's a space where love is both given and received. This description reinforces the notion that spa experiences have the potential to instil a sense of a healthier future in visitors and can serve as an educational platform for spa consumers, promoting well-being and self-care.

Motivations for SPA

Spa tourism offers a space for travellers seeking destinations with spa-related offerings and experiences. It is a sector within the health tourism industry that is experiencing growth and flourishing, as noted by McNeil and Ragins (2005). The motivations for spa consumption can vary depending on the location, with differing opinions.

Mak et al. (2009) conducted a study in Hong Kong that explored the motivations and characteristics of spa-goers. Their findings revealed that "relaxation and relief" ranked as the most significant motivating factor, followed by "escape." It's important to note that spa-goers worldwide represent a diverse group of consumers in terms of cultural and social backgrounds, leading to varying perceptions and ideologies driving their motivations.

For instance, American spa-goers tend to view spa experiences as rewarding, according to the ISPA (International Spa Association, 2006). In contrast, the Asian spa-goers in the study by Mak et al. seek spa experiences for physical and mental healing. In the UK, consumer motivations for spa experiences may encompass a mix of factors, reflecting the diversity of perspectives in this region.

In 2008, the International Spa Association conducted its Global Consumer Study (ISPA 2008) and found that the primary motivators for North American spa guests were gift certificates, recommendations from friends and/or family, endorsements from healthcare practitioners, complementary products or bonus services, packages, promotional sales, appointment flexibility to meet their scheduling needs. Compared to Mak et al.'s (2009) study, which focused on factors enticing tourists to travel, these descriptors can all be categorized as pull factors.

Social spa experiences have historical roots, with early instances of offering social and recreational activities in Roman baths (Wood, 2012). Social spa experiences have increased since 2012 and peaked in 2019. According to Kliucinskaite (2019), Generation Z is expected to be the predominant group seeking to connect with friends, family, and partners to share their spa experiences. Sharing a spa day allows everyone to escape their daily routines, relax, and engage in conversation while immersing themselves in the spa environment, as noted by the Good Spa Guide (2014).

The primary reason tourists seek out spas and wellness retreats is to embrace the concept of "wellness," with relaxation being a top priority and a significant motivator, as Chen et al. (2008) emphasised. This motivation takes precedence over recreational activities and enhances the quality of life. It reflects the notion that spa consumers are searching for an escape from their daily lives or work. Voigt and Pforr (2013), cited by Eojina et al. (2016), recognize that the daily stresses of living in a fast-paced economy create a need to escape to a tranquil environment, whether a local spa or a wellness destination located farther away. Both relaxation and escapism are compelling factors motivating tourists, as highlighted by Hsu and Huang (2008).

Sensory Marketing

The developed sensory marketing field explores the role senses have in consumer behaviour. Krishna and Schwarz (2014) refer to this as an engaging marketing concept whereby the consumers' senses affect their perception, judgement, and behaviour. When experiencing a service or using a product, it should gratify at least one sense – taste, sight, smell, sound, and touch, if not more. Krishna (2010) states that in the past, most firms discouraged the sensory aspects of products – hardly ever being mentioned. In the long term, this led to brands being detracted from other aspects of the product. Contemporarily, firms now observe and encourage sensory features to market to their target audiences.

The exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968) is the observation that the more often the consumer has been exposed to the things, the more they like them. The more clients are exposed to the same sensations, products and treatments in the spa environment, the more repeat visits, purchases, and bookings will likely be made for that business. Yozukmaz and Topaloğlu (2016) noticed that multi-sensory marketing is particularly present in spas, as the senses of sight, sound and smell are combined as part of the spa experience. In addition, touch connects the client with the therapist when receiving treatments. The power of touch is remarkably effective in reducing pain, lowering blood pressure, controlling nervous irritability, or reassuring a nervous, tense client (Beck, 2012).

Organisations must be made aware of buyer behaviour, particularly the inner layer, as that involves implementing sensory marketing (Randiwela and Alahakoon, 2016). When experiencing new environments, the body's different senses will interact with various stimuli - sight, smell, touch, hearing and taste- to create an ambience. A previous study conducted in a shopping mall to test the effect of ambient scent concluded that the odour directly affects the impression of buyers and has a considerable influence on consumers’ behaviours (Chebat and Michon, 2003, cited by Rathee and Rajain, 2017). Furthermore, smells significantly impact customers’ perceptions of product quality and the environment. The Global Wellness Summit (GWS) Trend Report (2019) highlights that luxury hotels allow guests to personalise and choose room aromas – improving the traveller's experience through scent.

Knowles (2001), cited by Randiwela and Alahakoon (2016), states that to communicate, brands and businesses aim to appeal to their audiences by successfully branding cognitively, also referred to as ‘emotional logic.’ In agreement with this statement, people can make decisions based purely on their feelings and emotions (hedonic) instead of rational thinking. Hedonic consumption has multi-sensory, fantasy, and emotional aspects tied to consumers’ interactions with products and services (Solomon, 2018).

Summary of Literature

The entirety of the literature review discussed numerous topics surrounding the types of spas, spa experience, consumption emotion, customer loyalty, memorabilia, motivations for spas and sensory marketing. In summary, the evolving spa consumer (Hu et al. 2019) seeks potential spas best suited to themselves based on reviews and word-of-mouth judgement. Therefore, it leads to a decision being made based on personal reasons or status, price margin (income), value and quality to set expectations before the arrival of the spa. It is known that satisfaction alone is not always enough to generate loyalty (Sethna and Blythe, 2019); however, satisfaction can influence re-patronage and repeat visits - creating retention for businesses (Liu et al., 2017). The OS is ascertained by emotions as a response to interactions (Richins, 1997), creating a ‘desirable impression’ on the consumer. TQM impacts customer loyalty through sensorimotor experiences, which acquire knowledge of the client base (market research) and form loyalty (Reitsamer, 2015). A key factor is personalisation – a ‘trend that is here to stay, states the Global Wellness Summit (2019) in the ‘Nutrition Gets Very Personalized’ trend. Research done by New Epsilon (2018), a global marketing innovator, indicates that in brands that offer personalised experiences, 80% of consumers are more likely to make a purchase and personalisation is found to be appealing to 90% of consumers. Clients in spas are looking for adapted treatments, personalised skin care products and more variety in treatment choices. It offers a unique experience and is specifically for them rather than standardised. Barnes (2015) adds that for a spa to offer the best experience, it comes with meeting a guest's specific needs and how the therapist as an individual can fulfil bespoke necessities.

After reviewing the literature, sensations (senses) and emotions are two themes that stand out the most. Both fit well with hedonic consumption in offering multi-sensory marketing in the spa industry (Yozukmaz and Topaloğlu, 2016). To create a memorable experience, inputting atmospheric cues and sensory memorabilia can encourage a lasting memory. Most of the references are from the hospitality industry and psychology research, indicating a gap in the market. How does the spa experience influence spa consumers, and what leads them to become loyal purchasers? This research will aim to extend the body of knowledge in the spa industry behind what motivates the spa consumer to visit a spa, how memorable experiences are created and what about the spa entices them to return.

Methodology

Methodology is the compass guiding the research journey, providing the roadmap for answering complex questions and unlocking the mysteries of knowledge. It's the art and science of choosing the right tools and techniques to unearth hidden truths and bring clarity to the research landscape. The methodology is the architect of structured inquiry, shaping the foundations upon which meaningful insights are built.

Introduction

This methodology section will discuss how the interpretive stance is advocated for this research into what motivates spa consumers to visit hotel/destination spas alongside the created memorable experiences. Therefore, determining an inductive theory. The ontological and epistemological approaches have been considered to rationalise the methodology. A key discussion involved is based on reflexivity (reflexive approach), whereby the relationship between the researcher and subject/topic is examined (Veal, 2017) to justify why, as a researcher, the topic is relatable and the rationale for further studying the specific industry. The research design was a questionnaire-based survey in an online, respondent-completion format. Snowball sampling was used as it proved most convenient as it targets a specific audience: spa consumers. Ethical considerations towards the study have been included within this chapter, detailing the reason for carrying out the research as compared to another. Further logistics are provided based on the reliability and validity of the data.

Ontological Considerations

To consider the study's methodological approach, ontological and epistemological phenomena are first examined to underpin the nature of the research. This determines the methodology and approach to the study and establishes the data collection tools. Creswell (2014), cited by Davies and Fisher (2018), mentions that when undertaking a study, there are several components in the research process, which are understanding the nature of reality or truth (ontology), the nature of knowledge (epistemology) and the strategy used (methodology).

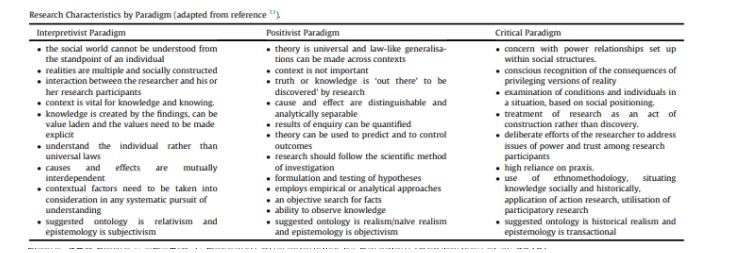

All of these considerations are justified in a research paradigm. Kivumja and Kuyini (2017) suggest three dominant paradigms, which are positivist, interpretive and critical. However, numerous ways exist to utilise and conduct research (Davies and Fisher, 2018). Cuthbertson et al. (2019) briefly outline that positivism involves a belief that there is a single objective reality to any research phenomenon or situation independent of the researcher's perspective. In contrast, interpretivism is the belief that reality is indirectly constructed based on individual interpretation and is subjective. The meanings of events cannot be generalised; therefore, people's assumptions and interpretations are distinctive. An interpretive approach allows the researcher to understand the participants' minds better and to see the world from different viewpoints (Veal, 2017). An interpretive approach has been applied to ensure that the study explored people’s opinions on memorable spa experiences and whether such experiences impact the senses. Further critical analysis will focus on the potential effect of spa experiences in becoming long-term, loyal consumers of a particular spa.

Veal (2017) states that ontology is a philosophy where different people perceive' reality' differently in an interpretive approach. Cuthbertson et al. (2019) further this by defining ontology as the ‘nature of reality in that the assumptions we make to believe that something makes sense, is real or is under exploration. Epistemology concerns the relationship between the researcher and the researched topic (Veal, 2017). Cuthbertson et al. (2019) add that it is how we know something and how it can be acquired and best communicated. From an interpretive perspective, the research will be subjectivist as individuals will impose meaning on the world and interpret it in a way that makes sense to them (Cuthbertson et al. 2019). A questionnaire was used to gather peoples’ opinions on the thesis topic of exploring memorable experiences in the spa.

The findings gathered will be opinionative, and values need to be developed through understanding the participant's interdependent factors. This demonstrates that characteristics from the interpretivism paradigm (See Figure 1) will be followed in this research. Generally, research focusing mostly on qualitative data analysis adopts an inductive approach (Thomas, 2003; Veal, 2017).

Thomas (2003) describes the inductive approach as a ‘convenient and efficient way of analysing qualitative data for many research purposes.’ In addition, it is also closely associated with the interpretivism philosophy (Knox, 2004). Buxton (2018) highlights that using qualitative methods in the service escape could provide more realistic and rich research not shown in qualitative studies. More exploration into what makes memorable guest experiences in the spa industry needs to be conducted qualitatively.

Reflexivity is effectively an explicit consideration of the relationship between the researcher and the subject that is researched (Veal, 2017, p.45). As a researcher, having experienced spas personally (physical relationships) and working in the industry as a spa therapist in various spa settings (day, hotel and destination spas), there have been many social interactions with spa consumers. Over the past two and a half years, spa clients frequently favoured indoor pools rather than outdoor ones in the UK and were shocked if a spa did not offer a large pool or wet area. This could be due to weather conditions or technical problems, which lead to pools or hot tubs being out of order. Many spa-goers prioritise treatments when booking a spa break and may prefer to spend considerable time engaging with the facilities when provided. However, spas with more accessibility and a wide range of facilities proved to be more time spent, leading to optimal happiness when checking out of their stay. The researcher's interests began by connecting with spa clients and seeing the change in stress levels from entering compared to leaving. This influenced the study area and was later developed, leading to a personal ideological framework being formulated towards the interest in memorable spa experiences. Further studies in this area are sparse, especially when considering the consumers, as they are the ones who purchase spa experiences and products. Mehmetoglu and Engen (2011) state that in terms of creating the ‘right’ experience, the industry demands specific knowledge of the content the customers need.

Data Collection Methods

An e-survey (Appendix 1) was designed to create an interpretive approach using Forms on Office 365 to target spa consumers with a recent or previous spa experience. Consent will be asked before filling out the e-survey, whereby they can choose to participate in the study based solely on opportunity and interest.

Originally, it was planned to conduct research at a chosen case study destination spa, involving printed questionnaires for spa guests and a semi-structured interview with the spa manager whereby further questions from the business perspective on the study would be asked. However, the coronavirus outbreak subsequently affected the overall study. Therefore, the mixed methods approach and the semi-structured interview had to be dropped, and an alternative data collection method was selected for the questionnaire. An interpretive approach will be applied as the data collection method is naturalistic (O’Donoghue, 2007), and each consumer has directly experienced a spa setting.

The proposed method used to answer the aim and objectives to gain more detailed and substantive knowledge was a mixed-methods approach. Tashakkori and Teddlie (1998) state that mixed-method studies combine quantitative and qualitative data in a single study by using two approaches to research. Therefore, integrating two different data types rather than just one approach provides a thorough understanding of the research study (Creswell and Creswell, 2018, cited by Truong et al., 2020). In recent years, mixed-method studies have become a common approach (Bryman, 2006) as they provide deeper insights and give a better understanding (Truong et al. 2020).

However, significant amendments were made due to the coronavirus epidemic, which resulted in only a questionnaire-based survey (e-survey). Questionnaire-based surveys are the most commonly used research method in leisure and tourism research (Veal, 2017), as they easily provide quantifiable data and provide individuals’ behaviours, attitudes and opinions towards a particular subject. However, questionnaires can sometimes lack accuracy and honesty if the participant answers questions that are or are not socially approved and may not give an honest or realistic answer.

The e-survey featured demographical information (age, gender), which can be classified as categorical data leading to either ordinal or nominal data. To diversify the types of questions asked, simple closed questions were initially used to indicate the legitimate agenda (O’Cathain and Thomas, 2004) to elaborate with more open questions later. Nevertheless, a large proportion of the research collected will be qualitative rather than quantitative, as open-ended questions will be used in the questionnaire to gather peoples’ opinions on the topic. A Likert scale, adapted from tourism research (Zatori et al. 2018), was inputted in the survey to recognise how the spa experience influences memorability.

To further the knowledge, a semi-structured interview with the spa manager from a chosen destination spa would have been able to explore their understanding of what contributes to memorable experiences and guest loyalty. In-depth or semi-structured interviews are conversational interviews (to an extent) and involve open-ended responses. This allows for flexibility due to the non-prescribed nature, whereby a checklist of pre-determined topics or themes is raised through prescribed questions (Veal, 2017). Although the interviewee may speak about additional information that describes a situation in greater detail or another topic voluntarily, the interviewer is encouraged not to debate with the interviewee.

An alternative way to carry out this research would be through observations. Observations were considered before starting the research as they have the advantage of being unobtrusive if done correctly; however, there are ethical issues with gathering information on consumer’s behaviours without them being given background knowledge of the study. Veal (2017) states that if subjects are made aware that observation is taking place, the research could be invalid as their behaviours and actions might be modified. Furthermore, emotions can be difficult to decipher (Veal, 2006). Observational research, when using unobtrusive techniques, does prove worthwhile as the research gives a realistic perspective (Veal, 2017) on what spa consumers do, how they act and what they look for when immersed in a spa environment. For example, O'Dell (2010) opted for observational research in Swedish medicinal spas to observe what people did in spas and how experiences are formed.

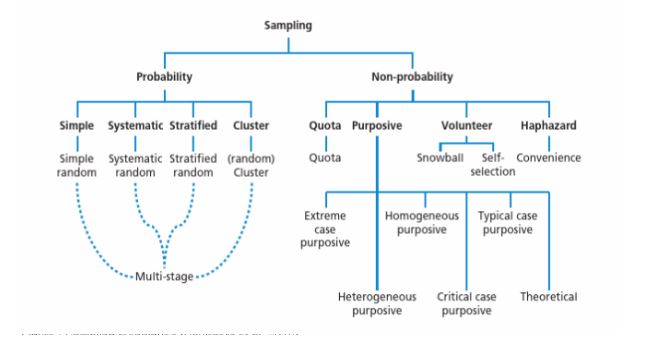

Sampling

Bhardwaj (2019) outlines that sampling is an important part of the research process as it selects an accurate sample (individual or group) from the population to fit the study's aim. Non-probability volunteer sampling (Figure 2) was deemed most appropriate for the study as the questionnaire is designed for anyone with spa experience. The e-survey can be distributed and circulated online through acquaintances, friends, work colleagues or family members.

A snowball sampling technique was used for convenience (Naderifar et al. 2017); it also allows existing participants to recruit new participants to participate in the research. The target population are spa consumers; they can volunteer to participate in the questionnaire by having relevant experience at a hotel/destination spa.

The sample size may not represent an entire population; therefore, findings may not be as accurate as they could be, resulting in a homogenous sample (Saunders et al. 2015). Due to the nature of the study, primarily spa-goers are the target population to gather questionnaire-based research. As a limitation, this could open up to regular spa-goers or first-timers, which could show differentiation in the data. Furthermore, there are limitations in targeting spa-goers due to locality and restricting time boundaries. It could be argued that at the particular time of the study, the target population is representative of the population of UK spa-goers.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics implies that there are guidelines regarding the standard of behaviour when conducting research involving those who become the participant(s) or those affected by the study topic (Saunders et al. 2012). Guidelines for any research need to be followed as it involves a selection of people taking part in a study to gather data around a particular area of interest. If this is not considered during the research process, then major consequences can occur. Ethical issues can arise at any point in a study, so the researcher needs to be aware of, able to address and prevent these problems to maintain the integrity and safety of themselves and the participants (Bryman and Bell, 2007). To do this, a decision should be made about what is morally right and wrong, as you do not want to cause any misconduct.

As a student at the University of Derby, the Code of Conduct (2017) on ethics was read and followed by the researcher to understand the process of collecting data within research. No such questions should be invasive or intruding on their private life, along with misleading information about the study. Therefore, a compiled brief explanation of the dissertation research and its purpose is provided. Following the Data Protection Act (2018), the e-survey states that participants' identities will be kept confidential and their participation is voluntary.

The e-survey responses (data) will be stored anonymously until they are no longer in use; they will then be deleted. No participants are to be identified, and their names and locations will be kept anonymous to ensure their protection.

Regarding the case study that was to be selected for this dissertation, to protect the business, it would have been given a name to protect its anonymity and to prevent misleading intentions for existing or future customers. Debriefs were not conducted as they do not apply to online surveys.

Logistics

Primary data collection through an online survey created on Forms through Office 365 was released on Friday, the 20th of March 2020, via social media platforms like LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram. Data collection lasted two weeks, and the questionnaire cut-off point was on Friday, the 3rd of April 2020, at 11:00 p.m.

Originally, the idea was to hand out questionnaires to spa-goers at a destination spa, where they could volunteer to participate. However, the coronavirus led to the organisation's closure, which would be used as a case study. The approval from the recruitment and marketing team was detrimentally affected and delayed the research process.

Data Presentation and Description

Data presentation and description are the creative brushstrokes that transform raw data into a meaningful narrative. It's the art of crafting visual and textual representations that convey the facts and reveal the underlying patterns and insights hidden within the numbers. This process breathes life into data, making it accessible and engaging for researchers and audiences, facilitating a deeper understanding of the information. In the research world, data presentation and description are the bridge that connects data to knowledge.

Findings

To further understand the collected data, the Forms survey responses (Microsoft Forms, 2020) were opened in Excel to be exported to SPSS software. All quantitative data could then be coded using a coding frame. Firstly, a codebook was implemented, and input was done from Excel to SPSS. However, qualitative data cannot be transferred onto SPSS as the software does not understand words, so a thematic analysis was conducted (Appendix 2). Keywords and phrases were identified as codes to develop common themes among the responses.

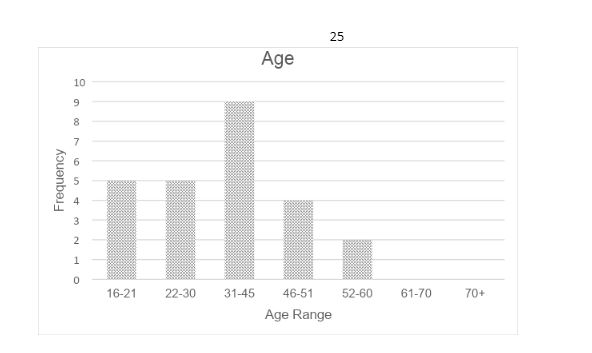

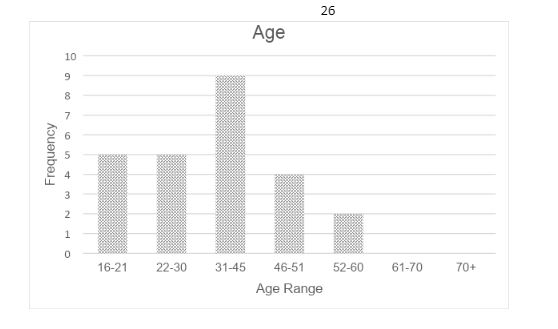

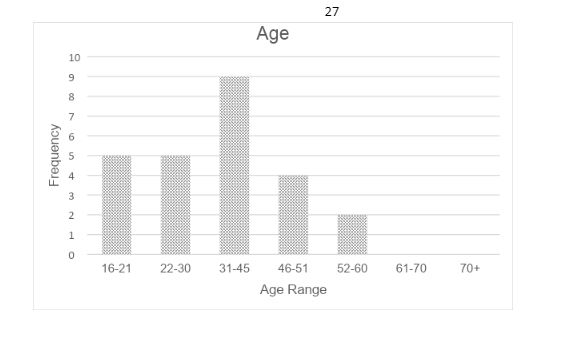

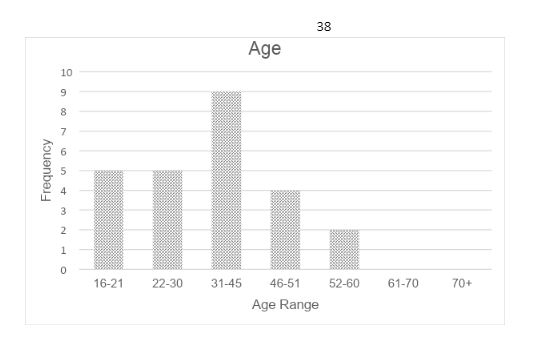

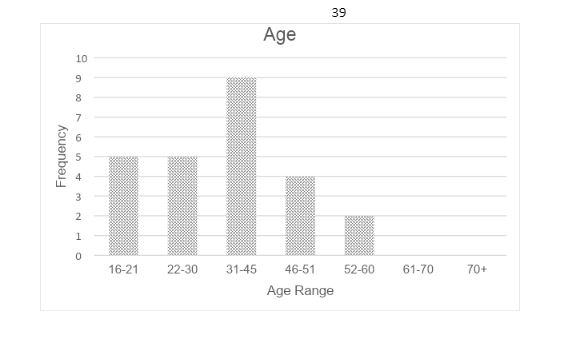

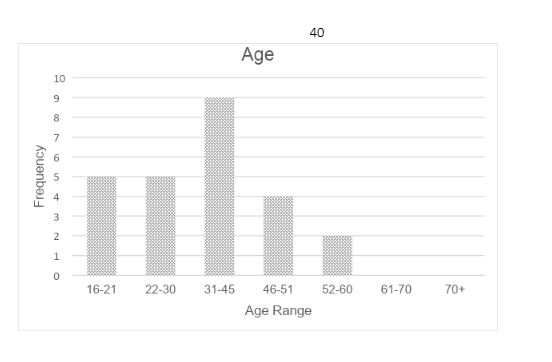

Twenty-seven spa consumers participated in the e-survey; 16 were fully completed, and 11 were partially completed. Two male and female participants who volunteered to undertake the questionnaire had not experienced a spa before. It was stated that participants should have had previous spa experience. For this reason, a decision was made that they were removed from the results because they were not in a position to provide valuable responses to the questions. Therefore, only 25 were considered to be presented and further analysed.

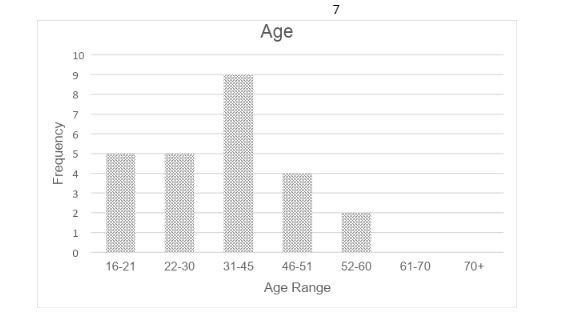

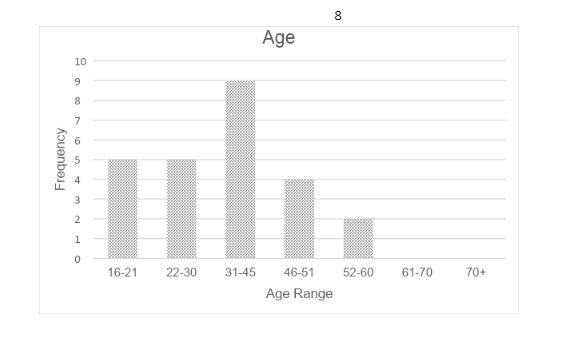

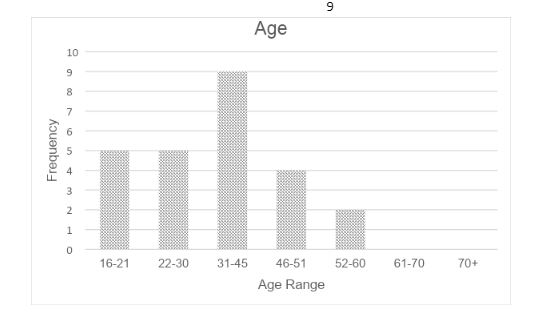

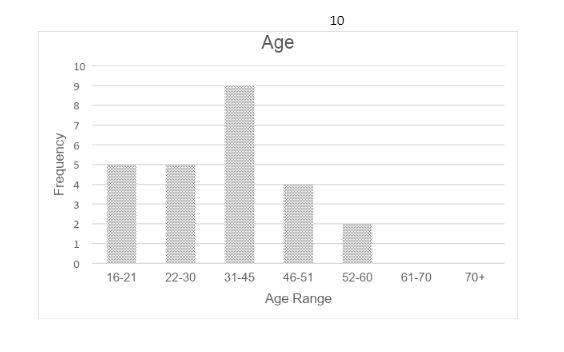

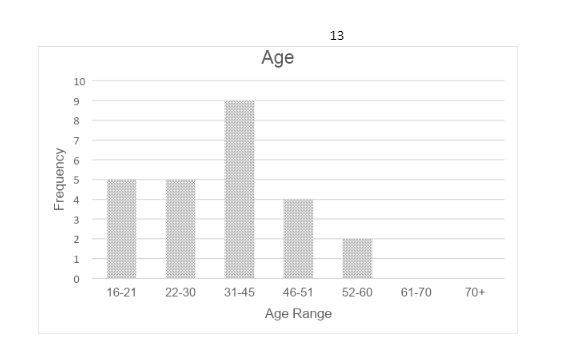

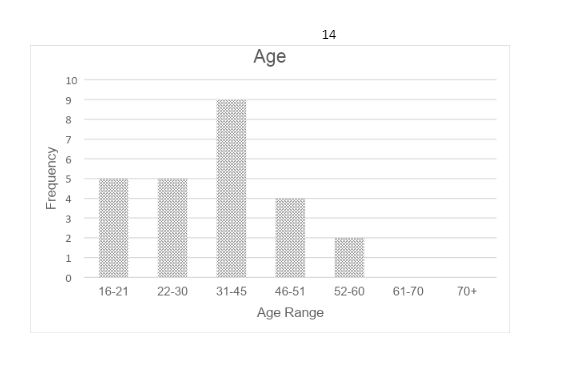

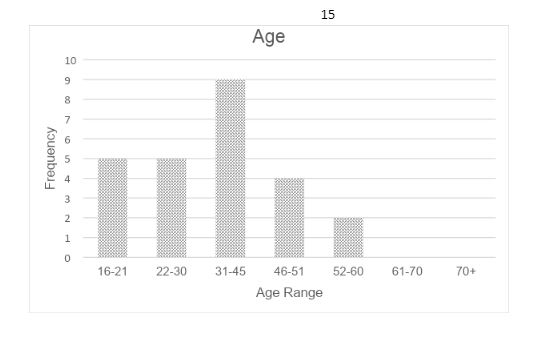

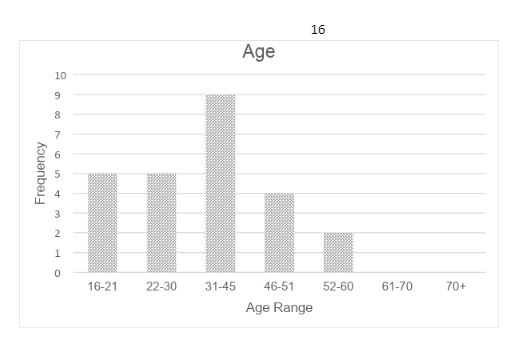

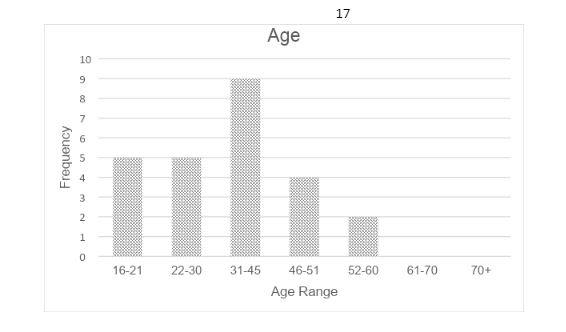

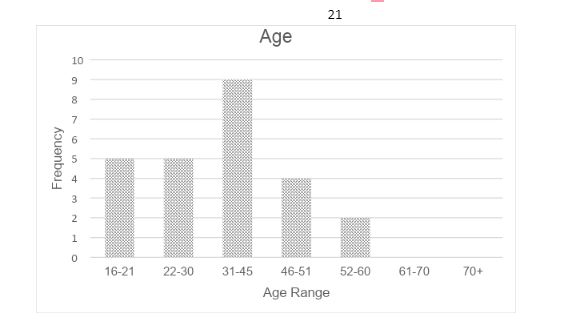

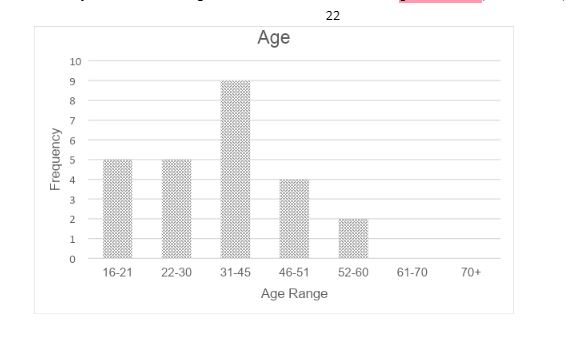

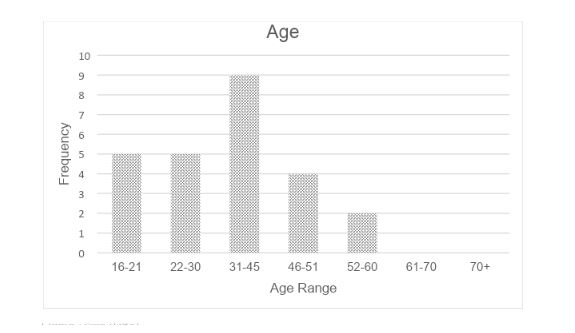

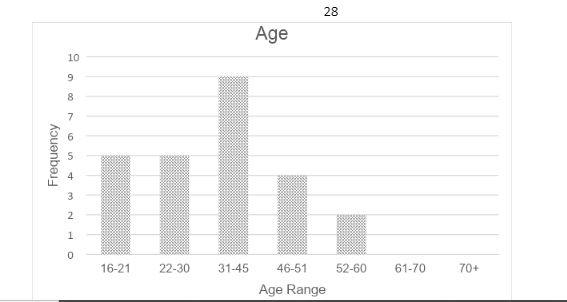

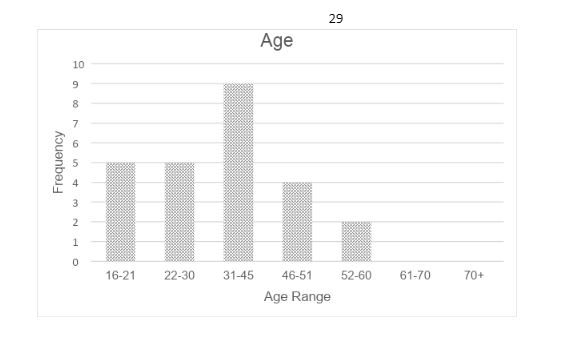

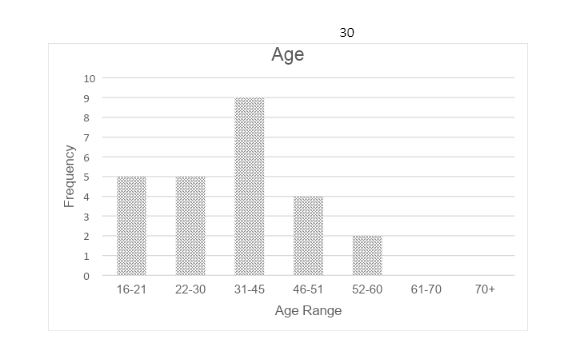

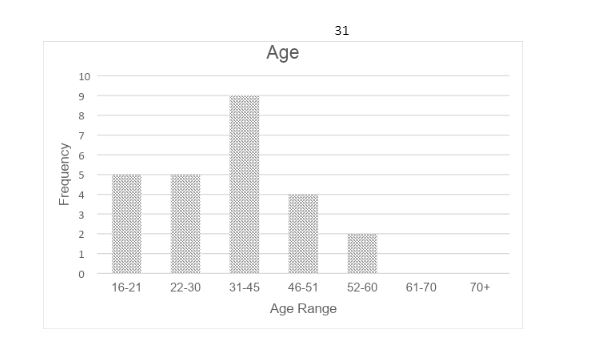

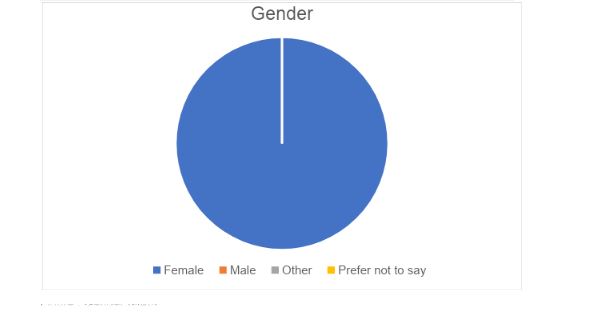

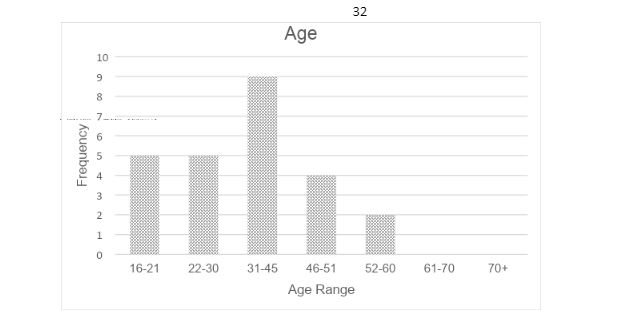

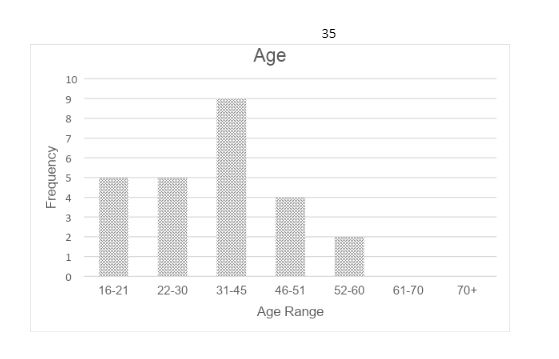

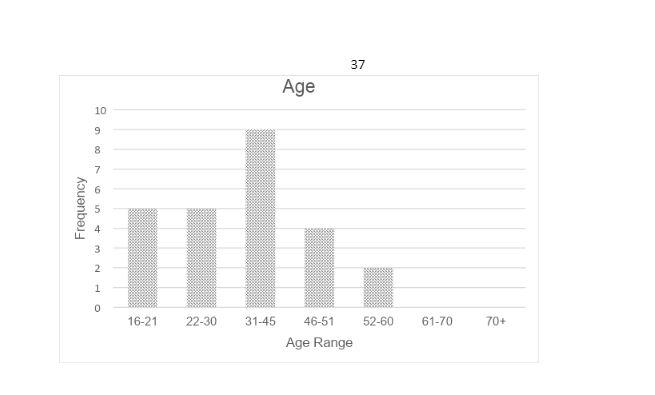

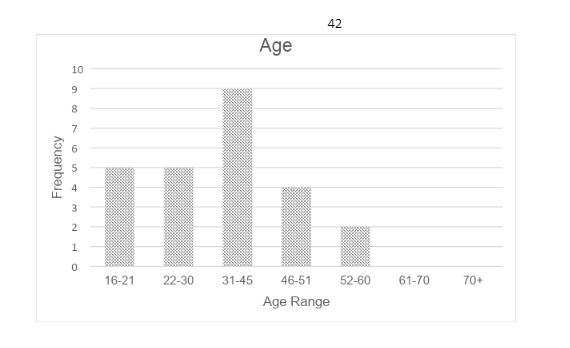

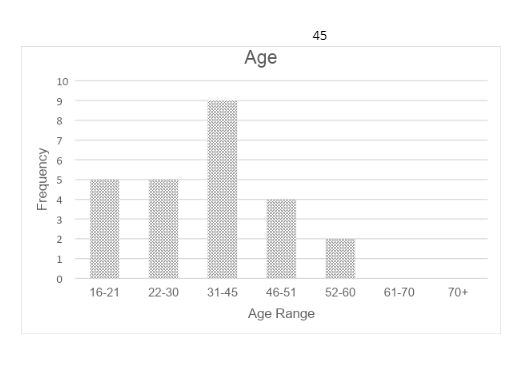

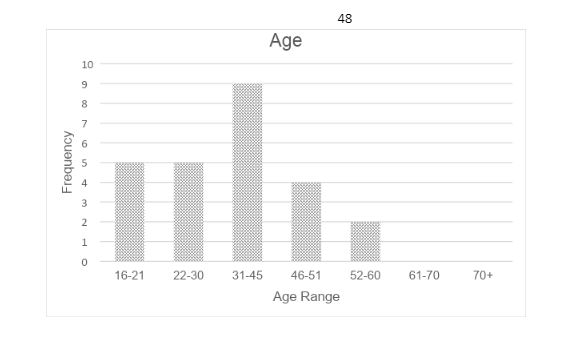

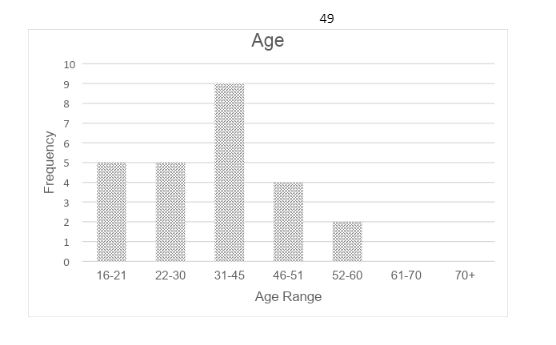

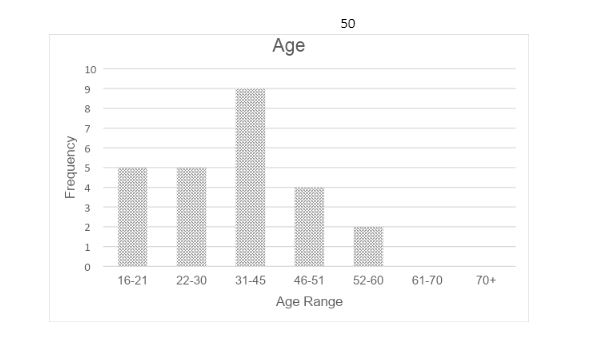

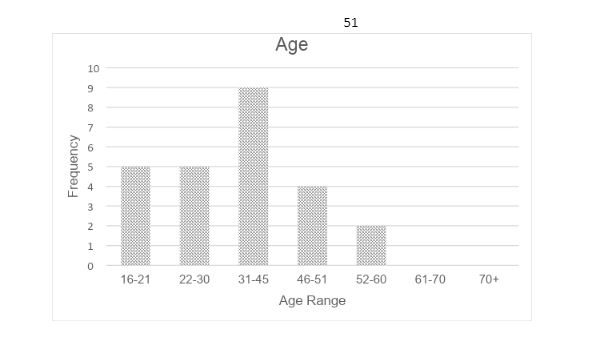

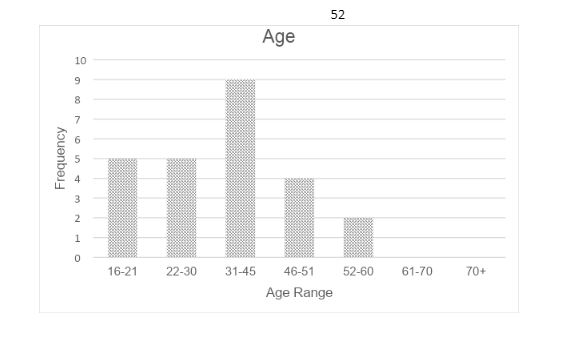

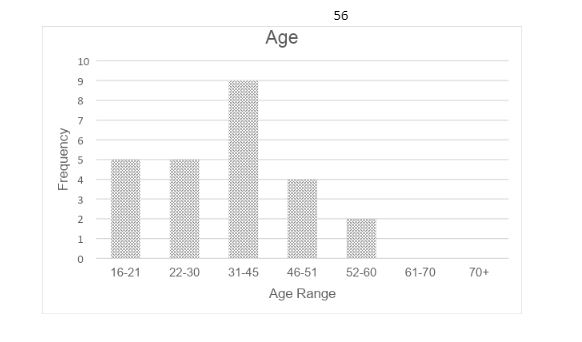

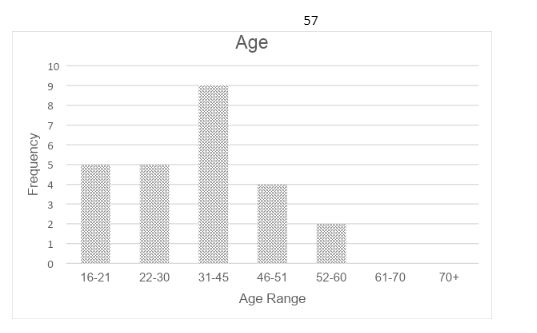

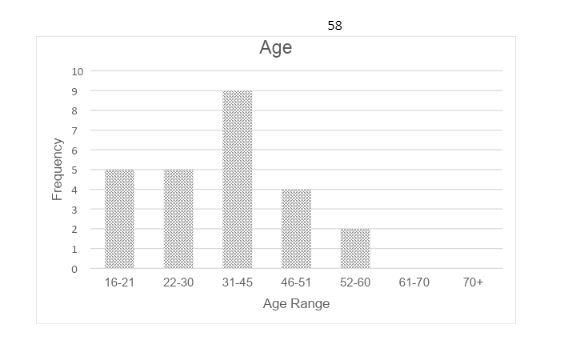

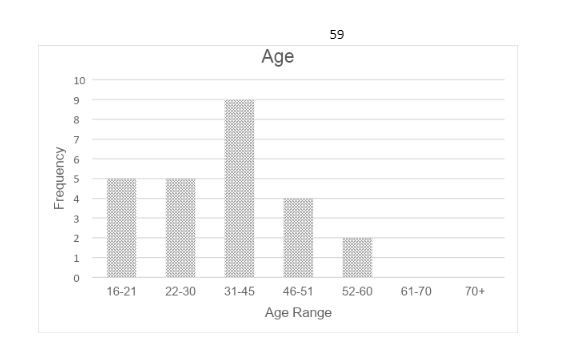

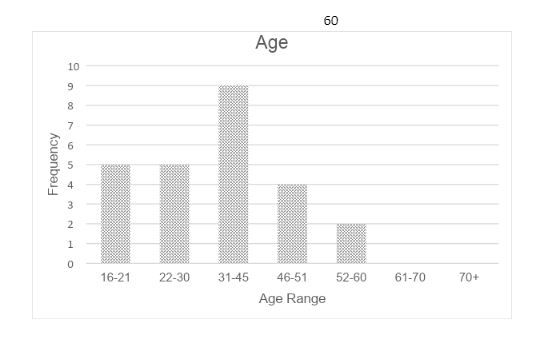

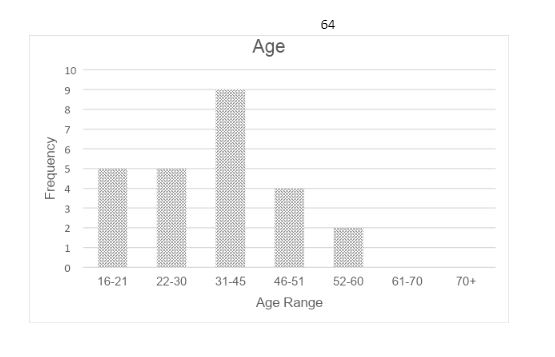

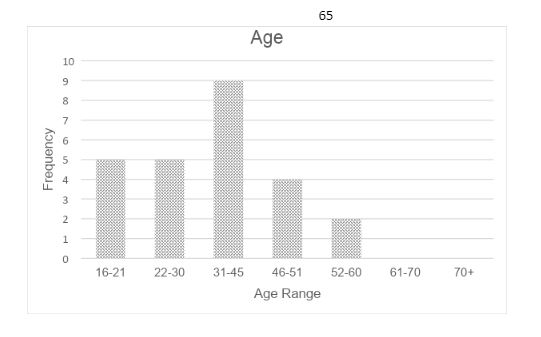

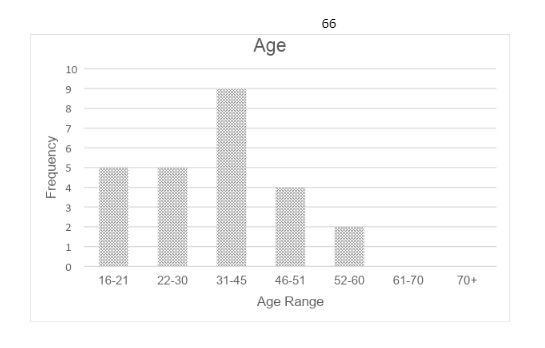

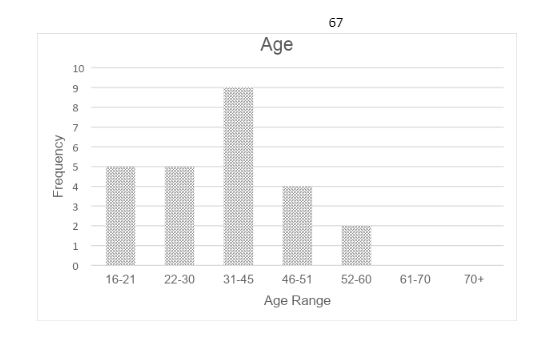

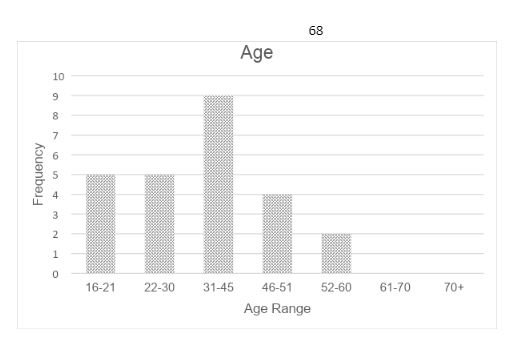

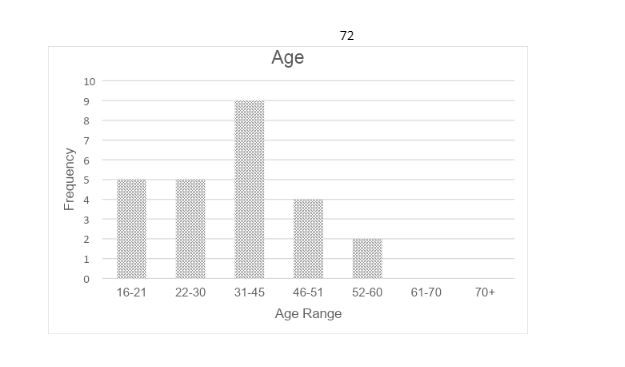

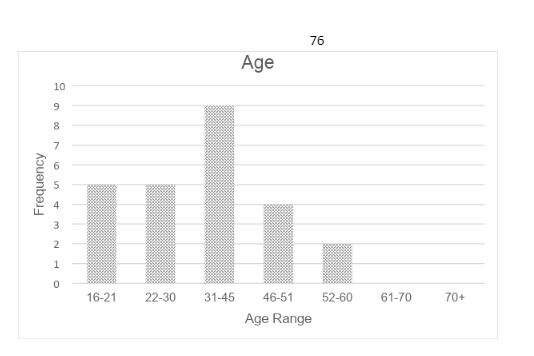

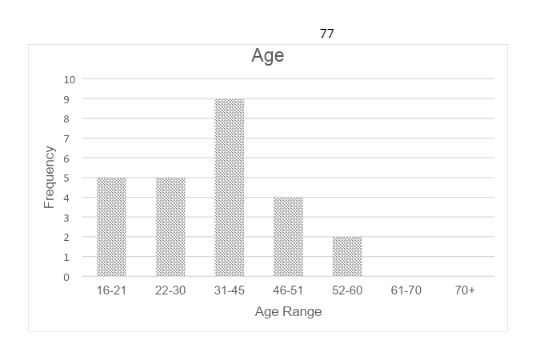

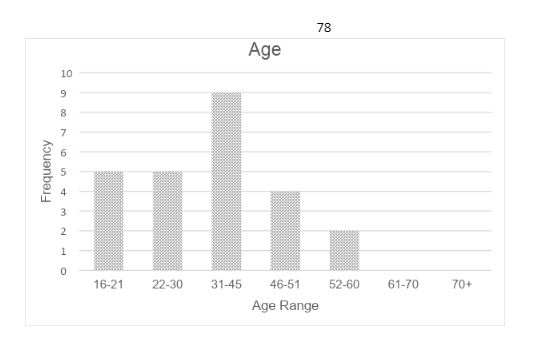

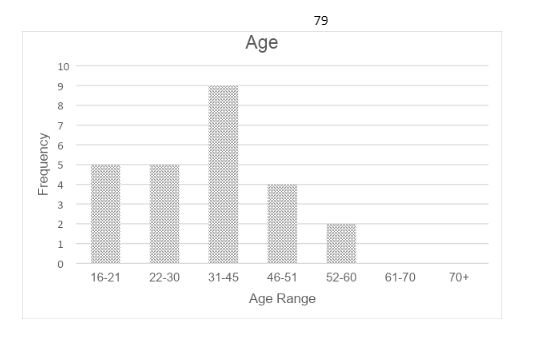

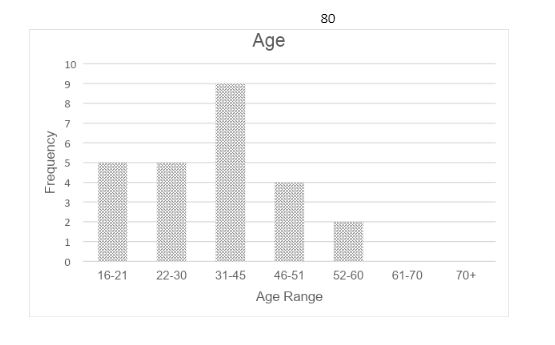

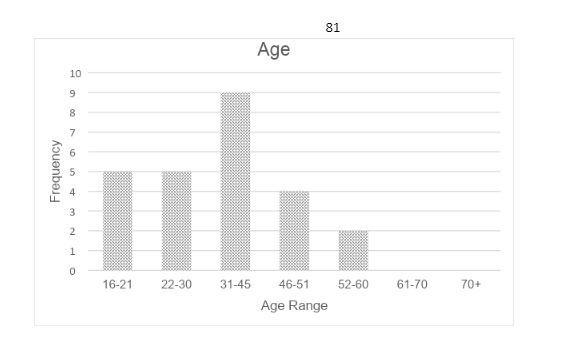

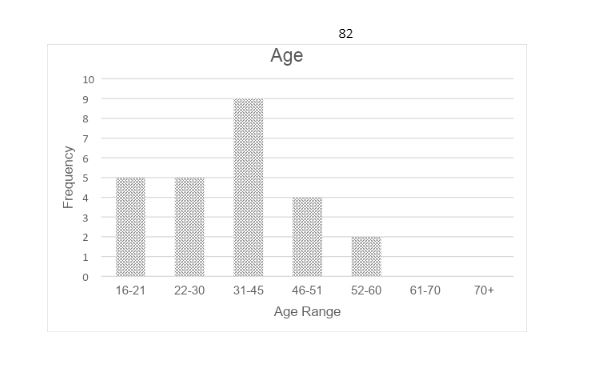

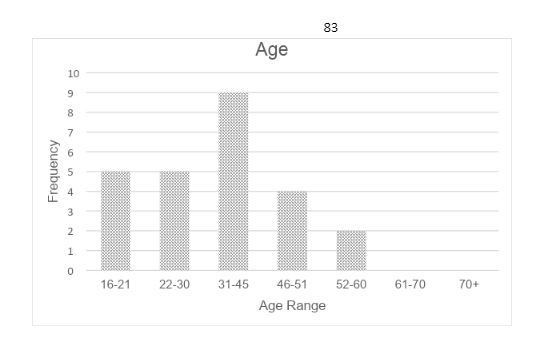

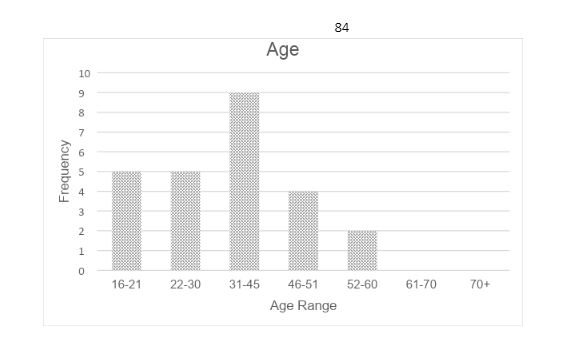

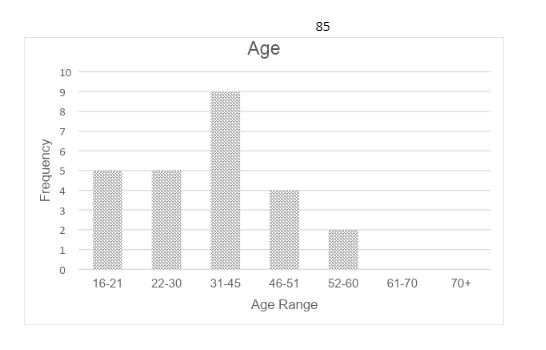

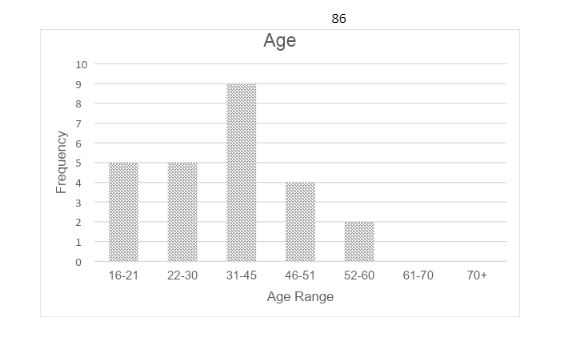

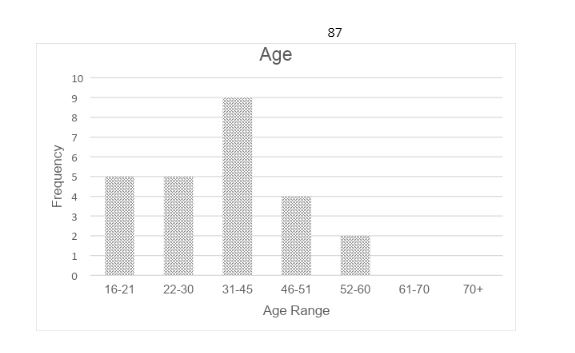

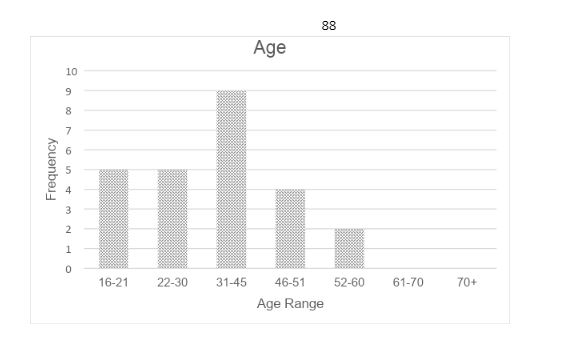

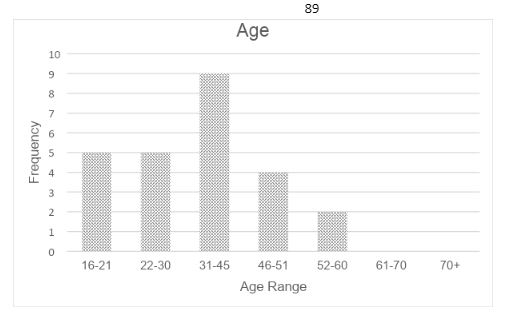

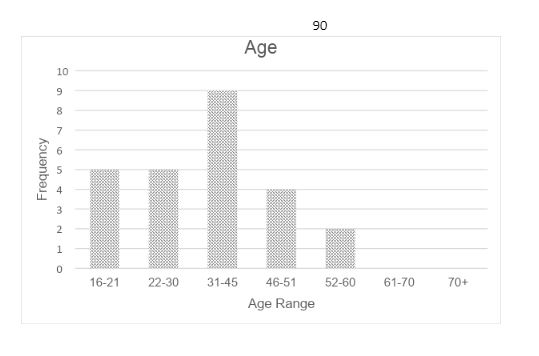

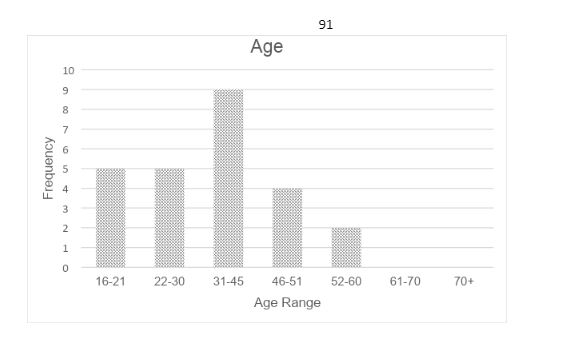

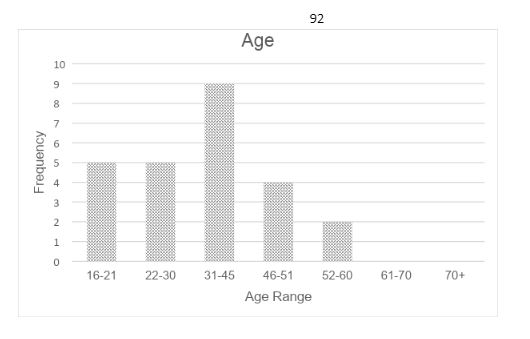

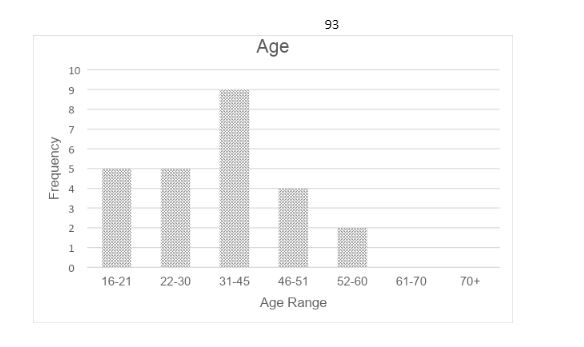

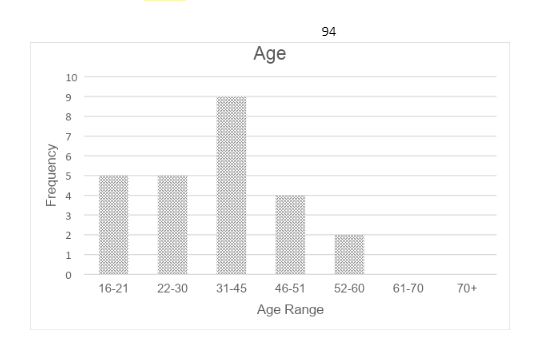

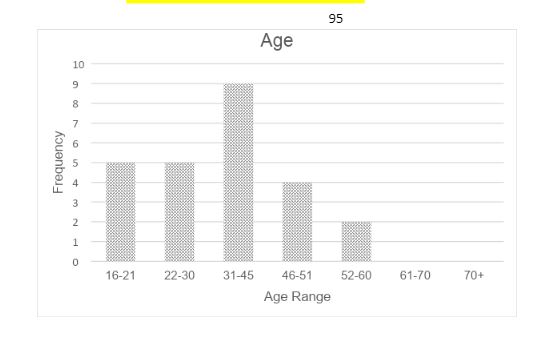

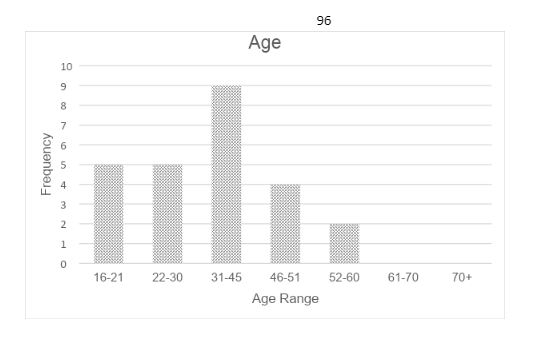

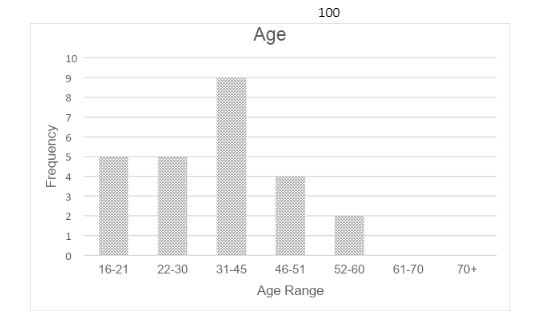

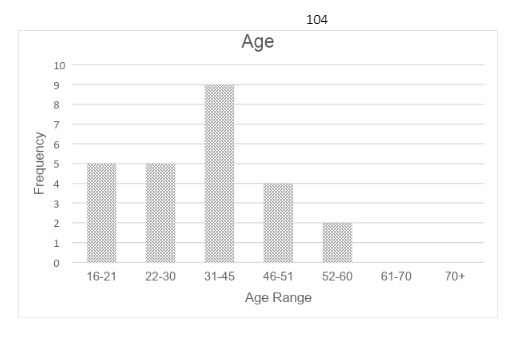

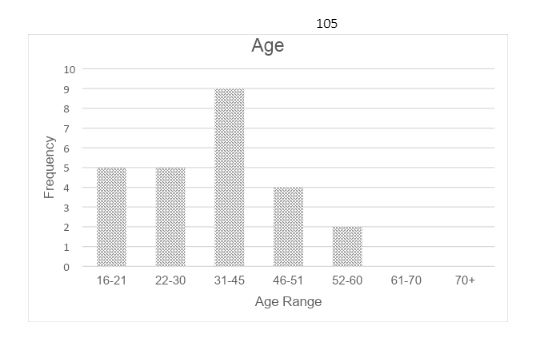

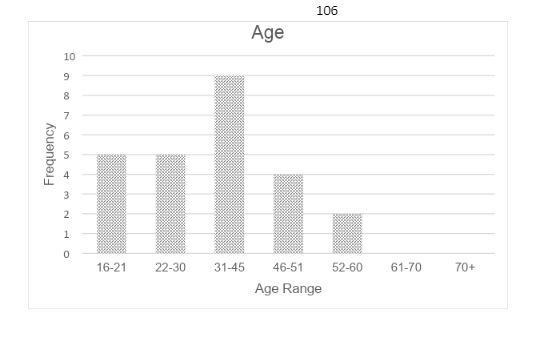

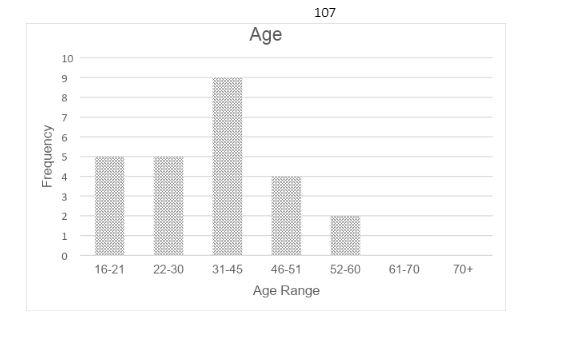

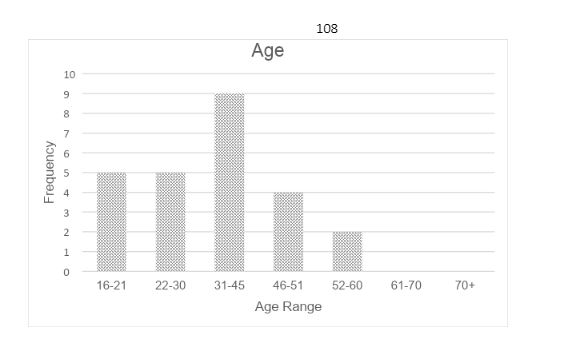

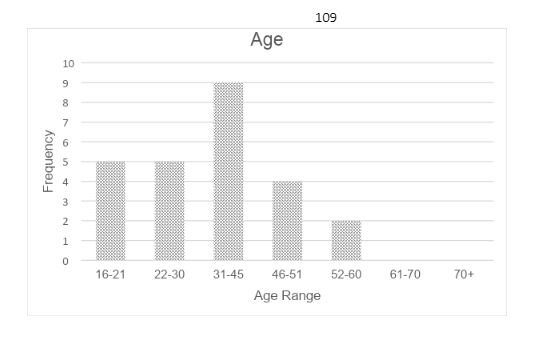

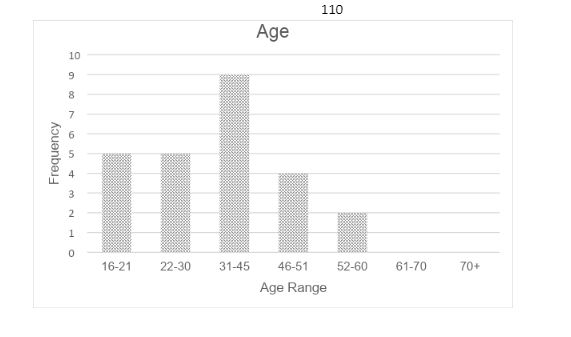

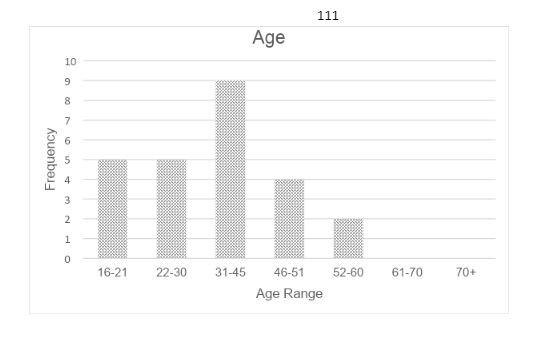

The main demographic of the participants was females (Figure 3) aged between 31-45 (Figure 4) with previous relevant spa experience (Figure 5).

All respondents had previous spa experience, validating the responses for further questions.

Respondents were then asked to describe this spa experience that was memorable to them. The keywords and phrases mentioned here were the treatments, work ethic (therapists), feelings and thoughts and the facilities they had experienced.

The most prevalent theme about memorable spa experiences was various experiences regarding facilities, followed by addressing how it made them feel or think and mentioning the treatment. This was highlighted in the following:

I like to be comfortable and warm enough to relax fully. We both enjoyed access to the relaxation room with water mattresses on the loungers. (Participant 13, Female, Age 46-51)

It was so quiet and relaxing. We had a full-body massage, and it was perfect. Followed by time in the steam room, sauna, etc. (Participant 15, Female, aged 31-45)

I go for the day with my husband, dip in and out of the pool steam and sauna room, and then have a massage treatment. (Participant 20, Female, Age 52-60)

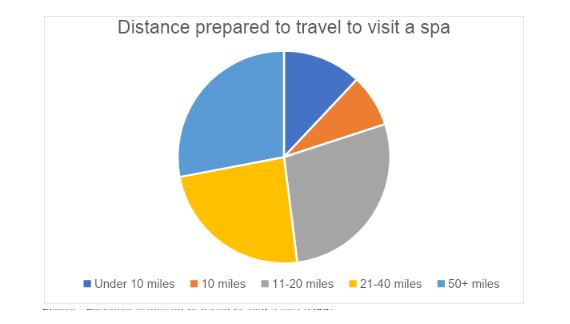

Regarding loyalty, the preferred distance people were prepared to travel to visit a spa (Figure 6) was between 11-20 miles and 50+ miles, both at 28%, closely followed by 21-40 miles at 24%. This could indicate that people prefer to visit spas that are relatively close by (driving distance), or if it is over 50 miles, then travelling abroad on holiday and then visiting a spa may be favourable to some. Only three

people (12%) are prepared to travel under 10 miles, which could be walking distance or a short car journey.

Figures 7 and 8 portray how spa consumers choose before visiting or booking a spa break. Before booking a spa, visiting the spa website (80%) to gain further knowledge was more popular than online reviews (20%). Respondent 10 stated they would have chosen both; however, this was not an option, so they selected the spa website.

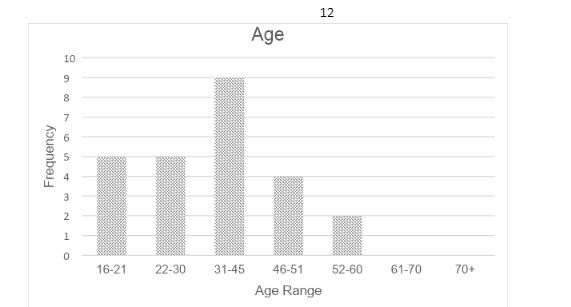

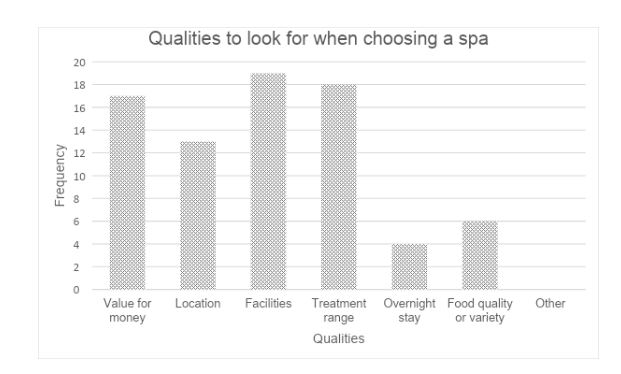

The top quality that the respondents identified when choosing a spa (Figure 9), in this instance, was the ‘Facilities’ followed by ‘Treatment range’, indicating that as spa consumers, they are searching for spas that offer a variety of good quality facilities and a range of treatment offerings. Indicating that the main qualities are what the spa has available, in both facilities and treatments. ‘Food quality or variety was second to last and ‘Overnight stay’ being the least selected.

To investigate the expectations of a spa experience, respondents were asked what their expectations were and why. Across each individual, the responses vary from one person to another. The most common theme of spa expectations is being relaxed or rejuvenated within a high-profile, luxurious environment:

To experience relaxation, comfort and de-stress as well as enjoyment. (Participant 6, Female, Age 22-30)

I feel restored and rejuvenated and ultimately better after the experience. A feeling of having been detected, cleansed, and buffed! Uplifted. (Participant 15, Female, Age 46-51)

It needs to feel serene and luxurious. (Participant 16, Female, Age 31-45)

Other responses factored in various expectations and created themes such as cleanliness, cost and happiness:

Cleanliness. Smells nice. (Participant 18, Female, Age 31-45)

The spa must be clean and have a calming atmosphere. Additionally, the treatments are always very expensive at spas. I expect spas to make the treatments more reasonable, and I often decide not to attend a spa if it is too costly, especially if there are not many facilities included in the price. (Participant 5, Female, Age 16-21)

To leave me relaxed and happy with my experience. (Participant 22, Female, Age 31-45)

Even other less frequent keywords and phrases can be addressed in specific responses, such as: “Education”, “Escapism”, “Customised treatments”, and “Healthy food”.

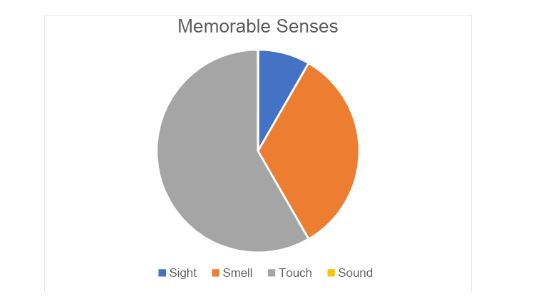

The senses are an important part of the spa experience; Figure 10 shows the most to least memorable senses when receiving a spa treatment. Interestingly, more than half the participants (58%) chose ‘Touch’ as their most

memorable sense, factoring in all the other senses (sight, smell and sound). The second most memorable is ‘Smell’ at 33%, which could be due to the scents inhaled when commencing and during treatment and the overall aroma of the environment in the treatment room. None of the participants selected ‘Sound’, which music is usually a part of every spa experience, especially in a treatment room.

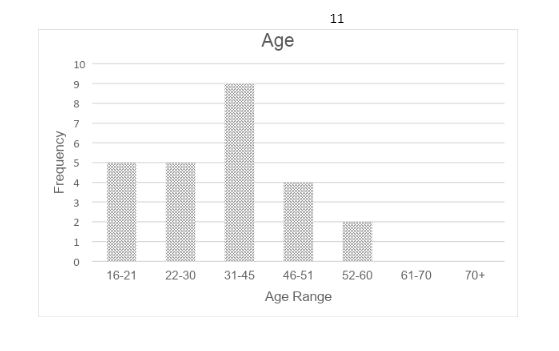

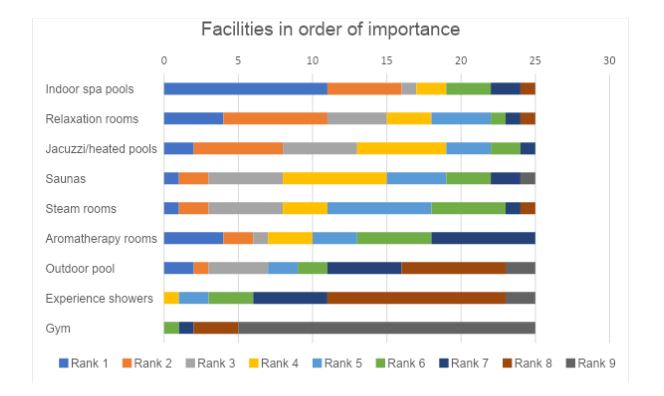

Participants were asked to rank numerous spa facilities in order of importance (Figure 11) using a ranking scale, with rank 1 being the highest importance and rank 9 as the lowest. The graph shows that indoor spa pools were the most important (44%) and gyms were the least important (80%). No participant ordered the facilities the

same as one another, indicating that the importance of facilities differs for everyone. This is reflected in Figure 12, as the facility types are in ranking order.

To further understand the importance of spa facilities, respondents identified the benefits of facilities on the spa experience as a whole. A prevalent theme for the reason behind how facilities benefit the spa experience was the feeling that they associate with facility use, but also how facilities benefit the experience:

It is a good way to unwind and gain valuable health benefits not only from treatments but from spa facilities as well. (Participant 2, Female, Age 16-21)

They make it more enjoyable and maximise the day rather than just going for treatment. (Participant 15, Female, Age 31-45)

Make you feel comfortable and relaxed. (Participant 22, Female, Age 16-21)

However, other respondents linked how facilities can be used to benefit after they have received a treatment:

It can increase feelings of relaxation and enjoyment. Saunas and steam rooms are my favourites as they help sweat out all the toxins from the body, help clear skin and bring feelings of refreshment. (Participant 6, Female, Age 22-30)

Making a day or at least half a day of the treatment day seems to prolong the value and benefits of the treatments experienced. (Participant 13, Female, Age 46-51)

Enhance the benefits of the treatments. (Participant 19, Female, Age 22-30)

Further key phrases people expressed here were: “Special”, “Highly important”, “Memorable”, “Feelings of enjoyment”, and “Furthers relaxation”.

Taking recent experience into consideration, specifics about what made their spa experiences memorable revealed that the relaxing environment and facilities were most prevalent, followed by the staff interaction:

There are many facilities in the wet area that I have not seen before personalised treatment when the therapist adjusts your needs and wants. (Participant 2, Female, Age 16-21)

Solitude, private, quiet areas. (Participant 7, Female, Age 46-51)

Being in a beautiful Italian hotel in Verona, being treated as a special person by a spa therapist and enjoying all the luxurious facilities. (Participant 21, Female, Age 52-60)

Participant 9 stated the lack of detail ‘oil on feet not mitted off’, which outlines that memorable experiences may not always be a positive spa experience. However, spa consumers remember bad experiences as they stand out compared to others. Eleven people associated a relaxing environment with “Luxurious facilities” or “range of facilities” and “rooms”; this suggests that spa guests seek solitude amongst a variety of facilities when determining a positive, memorable experience.

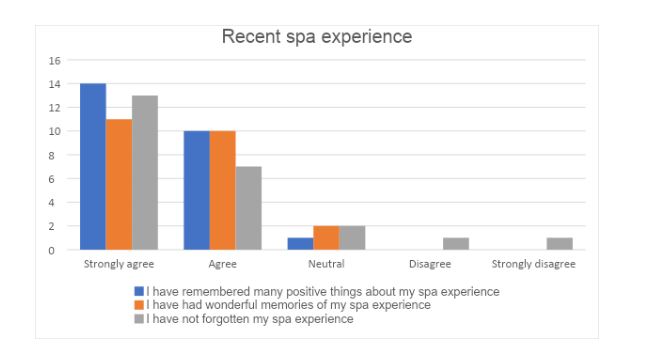

Following on from the previous question, in regards to the recent spa experience, the level of agreement with three statements using a Likert scale shows predominantly high levels that the respondents remember many positive things (56% strongly agree), have had wonderful memories (47.8% strongly agree) and have not forgotten their spa experience (54.2% strongly agree). Only one of the respondents disagreed, and another strongly disagreed with not forgetting their spa experience, indicating that they had forgotten their most recent experience.

Revisiting a spa shows customer loyalty and maintains the organisation's retention levels; people who have received a positive experience are more likely to revisit. The popular opinion that made respondents want to revisit a spa revolved around the quality of customer service and staff, shortly followed by the quality or variety of facilities and treatments:

Outstanding and friendly customer service, choice of the facilities in the wet area, product range used in treatment and treatment itself. (Participant 2, Female, Age 16-21)

Politeness of staff, quality of massage, sense of relaxation, venue. (Participant 17, Female, Age 31-45)

Good quality of treatments and range of facilities, customer service. (Participant 21, Female, Age 22-30)

Some respondents opted for treatment quality or variety, and others favoured the variety and quality of facilities, with few mentioning both.

Other respondents considered the overall experience or impression, the cost (value for money) and the locality:

All-round package of the spa from the staff to the facilities. (Participant 19, Female, Age 46-51)

The overall impression from entry to exit. (Participant 15, Female, Age 46-51)

Value for money. (Participant 12, Female, Age 31-45)

Good treatments, location and price. (Participant 22, Female, Age 31-45)

In addition, respondent 8 said they have not been to the same spa more than once as they “like to experience new spas when travelling to different places.” However, the last spa they visited, they would go back again. Due to it being relaxing, experiencing a unique massage and being able to socialise. Opposingly, respondent 22 said she would revisit the spa specifically for massage treatment as she experiences bad back pains, stating, “I'm a full-time mum, and I don’t get a lot of time for myself.”

Contradictory to the previous question, respondents were asked what would negatively affect their return to the spa (put them off). The majority of responses identified a theme around poor customer service, either being unfriendly, rude, no communication or bad treatment standards. The cleanliness of the spa environment and maintenance problems with facilities followed this:

Poor communication between staff and customers; lack of skills in solving problems and making decisions; unfriendly staff and therapists who are not passionate about their job. (Participant 2, Female, Age 16-21)

Rude Staff and dirty facilities. (Participant 7, Female, Age 31-45)

Lack of cleanliness, being too busy, no attention to detail and unfriendly staff. (Participant 15, Female, Age 46-51)

Bad customer service and terrible rebooking treatments at short notice. (Participant 20, Female, Age 22-30)

“If the spa is not well maintained.” (Participant 23, Female, Age 52-60)

Other themes identified were based on few or no facilities with poor interiors, overpricing or cost and the busy environment due to overbooking. This showed that the respondents would not revisit a spa with unfriendly staff, bad customer service and lack of operational management coordination, and cleanliness and maintenance issues.

Analysis and Discussion

Analysis and discussion are the intellectual sparring partners in the research arena, where data meets interpretation and insights emerge from the depths of information. The analysis is the meticulous surgeon, dissecting data into its fundamental components, while the discussion is the eloquent storyteller, weaving these components into a coherent narrative. Together, they form the heart and soul of research, breathing life into facts and offering a platform for critical thinking, debate, and the illumination of new perspectives. In this dynamic duo, knowledge takes shape, and discoveries find their voice.

Demographics

The results establish a generalisable sample as there is a diverse age range across the board of age categories, the majority being aged 31-45, and the participants were all female with previous spa experience. This does not come as a surprise as it is a female-strong industry, as women frequent spas more often than men. According to industry research, only 22% of men in the UK go to spas, while 78% of the women will book a spa treatment (Kliucinskaite, 2019). Therefore, the main demographic of spa-goers has been captured.

Memorable SPA Experiences

The primary collated data expressed that memorable spa experiences are created by experiencing relaxation through engaging with various facilities and having a beneficial and effective treatment, either by mentioning their thoughts or feelings. Findings from Chen et al. (2008) resonate with similar themes, with relaxation being highly important and a key motivator of experiencing wellness. Furthermore, this is reflected by the most memorable sense, touch, carried out through contact with the therapist when receiving a spa treatment.

This connotates signs of multi-sensory hedonic consumption (Solomon, 2018), whereby the consumer can build emotions tied to their interactions with different environments and during treatments. Furthermore, Randiwela and Alahakoon (2016) proclaimed that sensory marketing can influence buyer behaviour and, ultimately, purchasing decisions that are based purely on their feelings and emotions (hedonic) as opposed to rational thinking (Knowles, 2001). One respondent described a memorable spa experience as “Personalised customer service that makes you feel really special.” This can greatly benefit the consumer; as Meszaros (2018) mentions, upselling personalised products and treatments helps satisfy the consumer's desires.

Distance of Travel

To determine consumer loyalty levels, the distance consumers travel to pursue a spa experience varied between 11-20 miles and 50+ miles, closely followed by 21-40 miles. This shows that some may prefer to visit and support local spas, indicating they engage with ‘home-destination loyalty’ (Perdue et al. 2004) compared to others who go on vacations to seek a spa. When cross-tabulated with age (Appendix 3), it was clear that younger participants (Generation Z) preferred to travel a shorter distance than older participants (Millennials, Generation X and Boomers). Perhaps this is because middle-aged people tend to have more disposable income as they work full-time to support their own families and can manage their money well. In addition, older people may have more time and perhaps might be retired compared to teenagers and young adults as they may still be in education or have young children to look after. Mya (2019) states that millennials prefer their local surroundings and would much rather travel on local buses and trains to experience their local landscape in places they may not see. Another aspect may be that they have access to a personal vehicle that allows them to travel further away from the field than a young spa consumer without transportation.

Influences of Spa Choice

Most respondents (80%) prefer to view the spa's online website and are influenced by word of mouth (42%) to decide which spa they would consider visiting. It allows them to judge the quality and better understand what the spa offers. This is ultimately better for the companies as it means that customers rely on and view their actual website rather than look at online reviews to judge other people’s opinions and experiences. Additionally, word of mouth provides more trusting information when discussed with

a friend, family member or work colleague. Contemporary consumers educate themselves through the internet, word-of-mouth, and social media channels (Mandelbaum and Lerner, 2008), which is clear from the primary data collected.

Qualities Identified When Choosing a SPA

Facilities were the main factor that the respondents looked for when choosing a spa; the treatment range and value for money closely followed this. Similarly, they expect that prices for treatments are more reasonable and they “get what they pay for” without costing “an arm and a leg”. The findings of this study support those of Hu et al. (2019) that the evolved spa consumer is capable of identifying a spa they intend to visit based on value and quality, as the respondents were more likely to revisit a spa with high quality that is maintained throughout the full environment and expect value for money.

Expectations of SPA Experience

The fact that spa experience expectations had mixed opinions showed the individual differences of spa consumers; however, the prevalent theme was the feelings of relaxation that connotate from the luxurious surroundings and how the staff treats them. As there are a variety of responses, this supports the underlying literature that every spa guest has their reasons for visiting spas, either emotional, physical or both. Lo et al. (2015) further add that a spa is a very personal service, and the interaction with the employees greatly influences the customers’ experience. Throughout the spa experience, the spa consumer relies on the therapist and staff to guide them to feel these emotions of relaxation. Similar to what Champalimaud and O’Connell (2019) made apparent, spa consumers can leave feeling ‘mentally relaxed and rejuvenated’, which is the most important motivating factor before ‘escape’ (Mak et al. 2009). Escapism was only mentioned by one respondent and, therefore, not a significant theme.

The existing theory states that rejuvenation, relaxation, and revitalization are the main priorities in the day, hotel, and destination spas (Renard International, 2007), supporting the primary data theme of spa consumer expectations. The findings support that high expectations of the spa environment and experiences are made aware as consumers expect high service standards, a range of facilities and customised treatments. It partially contradicts Sipe and Testa's (2018) findings of memorable experiences being heavily associated with aesthetics and escapism, as escapism was not what they expected from a spa experience. However, the respondents do mention the spa's aesthetically pleasing representation or ambience.

Memorable Senses

When receiving a spa treatment, touch was the most memorable sense (58%), followed by smell (33%); however, respondents did not believe that sound was their most memorable sense. This confirms that the power of touch remains highly effective (Beck, 2012) and what is remembered if and when receiving a treatment. Smells, including fragrances and aroma, were the second most memorable, which is understandable as they help calm and ease the individual's mind.

Regarding personalisation (GWS, 2019), many therapists allow spa guests to choose certain scents they use for the treatment, inviting them to choose and smell and slowly introducing them to their personalised scent as they begin the treatment. These findings may raise awareness that although service cues that consumers are exposed to upon entering a spa, such as the appearance of staff, appearance of physical facilities, music and sound used, lighting and fragrance, should match with the theme of the spa (Lo and Wu, 2014), not all of the senses they are exposed to become memorable. Solomon (2018) explains that perceptual selectivity occurs as only a selected stimulus is taken on board out of multiple stimuli that are exposed to the consumer, which is most likely present in the spa consumer process. The theoretical analysis explains the relationship between the sounds (music) played in the spa environment and treatment rooms. Perhaps more engaging sound therapies should be implemented within the spa experience as GWS (2020) reports the growth of wellness music through the use of meditation apps to new developments of ‘AI-powered music apps and technology platforms that pull your biological, psychological and situational data to create an utterly unique, custom-made-for-you, an always-changing soundscape to improve your mental and physical health any time you want to tune in’ (p.78). If spas can implement resources to engage all five senses, it will create an ambience for the spa consumer and could be used to aid marketing strategies.

Facilities Level of Importance

The research shows a relationship between the most important facilities and how they benefit the spa experience, with indoor spa pools of the highest importance followed by relaxation rooms and heated pools. It determines that spa-goers aim to elongate those relaxing feelings, “prolong the value”, and provide further health benefits. Contrary to the findings that overnight guests visiting destination spas create wellness sustainability, primary research showed overnight stays were not the main priority when choosing a spa. These results may be because not every respondent had sufficient destination spa experience and may have answered only having been to hotel spas or day spas. Consequently, it impacts the reliability of the primary data collected. Water is one of the main necessities needed in a spa and the heart of it all (Crebbin-Bailey, Harcup and Harrington, 2004); having a spa without a direct source or access to water internally and externally is unconventional.

Various spa experiences and facilities enhance the spa experience as they can spend more time engaging in a relaxing environment. Confirming the findings by Dimitrovski and Todorović (2015), less prevalent themes express that “education” was what respondents expected from a spa experience. Educating spa guests will help them to develop these healthy lifestyle habits that they can take on board post-visiting. By moving around numerous spa facilities, they can switch from hot to cold experiences that leave them having “feelings of refreshment” and further enhance the benefits of treatments. This was also identified as a theme of how facilities benefit the spa experience. Furthermore, gyms

were people's least important facility; this may be because the average spa consumer does not book a spa break to exercise but for relaxation.

Benefits of Facilities in the SPA Experience

The predicted strong connotation with facilities being the prime necessity that spa consumers look for was backed up with qualitative questions, which allowed for a further detailed understanding of how facilities benefit the spa experience. Findings indicate a prevalent theme of further enhancing emotions/feelings received by using the facilities and the following benefits. As Lo and Wu (2014) pointed out, these post-consumption emotions play an essential role in consumer response and are vital to overall satisfaction (Lee et al. 2015). The difference in emotions varies from enjoyment and relaxation to refreshment and relieving stress. Industry studies claim that emotional value is the top factor for improved customer loyalty (Forrester, 2016, cited by Sipe and Testa, 2018).

Recent SPA Experience - Memorabilia

Continuing on recent spa experiences, the predominant theme of memorability was the relaxing environment, the facilities, and social interaction with staff. These themes were also present in the respondent's descriptions of what they associate with a particular spa experience that was memorable. However, this research allowed for concurrent responses detailing the key specifics of memorabilia. Being able to ‘relax and unwind’ is most important when experiencing

spa, as 60% of UK spa-goers imply (Champalimaud and O’Connell, 2019), and to do this, spa consumers must be exposed to relaxing surroundings that are easy on the eyes, have a sense of simplicity when exploring rooms and experiences with ease combined with welcoming and helpful employees.

Recent SPA Experience – Level of Agreement

Statements adapted from tourism researchers Zatori et al. (2018) memorability scale items, the respondents expressed an overall positive impression towards their spa experiences as a large proportion could remember positive things, had wonderful memories and had not forgotten their spa experiences. This shows that the majority of spa consumers had a positive spa experience; however, two respondents confess that they had forgotten their most recent spa experience, either from not being suppressed in their memory, which caused them to forget their experience or after having a negative experience they have disassociated from their mind.

Aspects of Re-visiting a SPA

More informed responses on the considerations that would make the spa-goers visit again show that they concentrate on the quality of customer service when considering re-visiting a spa. This was coupled with the quality or variety of facilities and treatments. The prevalent theme here is quality, which impacts the spa's first impressions and prior judgments (Reitsamer, 2015) and post-experience. Although, satisfaction alone is not entirely enough to generate

loyalty (Sethna and Blythe, 2019), the service or, in this instance, quality customer service influences whether the spa consumer is most likely to revisit the spa (Hu et al. 2019).

Aspects of Not Re-visiting a SPA

Alternatively, a theme based on poor customer service would make them less likely to re-visit again, as well as low levels of cleanliness and an unhygienic environment. Undeniably, these are the main attributes of any operator within the customer service industry. It is important for not only the safety of customers as they need to be able to relax and enjoy the spa experience without concerning both physical and personal safety and privacy and the standard of cleanliness of the facilities (Lo et al. 2013 cited by Lo et al. 2015) but for employees as well. If the standards are not to a guest's liking, then it may detrimentally affect their confidence levels and trust in the spa. Customer service is the dominant theme about returning or not, and to provide professional high standards, every new customer must be treated with the same enthusiasm and respect as a repeat customer. Positive interactions between the employee and spa guest can be all it takes to make the experience memorable for the consumer. The shift from a tangible service to an immersive experience is made distinct by Sipe and Testa (2018). Without any emotions or meanings attached to the experience, the memories may not be as the last longing (Tung and Ritchie, 2011, cited by Sipe and Testa, 2018).

Summary of Findings

The main highlights from the research are that memorable experiences are primarily based on relaxation built through the overall experience, including the level of engagement with facilities and treatments and the communication or interaction between employees and spa consumers. Each of these stimulates emotions and feelings towards the atmosphere of the spa environment and is based upon the organisation's overall functioning, whether they can succeed in both variety and quality across these three aspects. Younger spa consumers may be more inclined to visit local spas that are 11-20 miles away, thereby becoming supportive and loyal to the business. In contrast, older consumers can travel further afield as they perhaps have more time, money and access to a vehicle. This enables them to travel 50 miles to vacation for spa and wellness. Contemporary spa consumers (on average) are well educated in searching for spas that suit their needs and desires as they view online websites and use word of mouth to find new information when considering which spa to book. The precise influences are based on value and quality, with facilities necessary for a spa experience. Responses were broad regarding spa expectations; however, this proves that everyone is different and has different motivations for seeking a spa. Overall, spa expectations are to be of high standards with luxurious surroundings, personalised treatments, a range of facilities, and high levels of customer service. Indoor spa pools were the most important facility due to the heavy association of ‘taking the waters’ in spas.

It should be clear that touch is remembered most during spa treatments, followed by smells and sounds. Indoor spa pools were the top-ranked facility for the spa experience, followed by relaxation rooms and heated pools. Gyms were bottom-ranked and, therefore, unimportant for the average spa consumer. The purpose of facilities is to enhance further the emotions or feelings and the benefits of treatments. Recent spa experiences showed the themes that correspond with memorable spa experiences, and most respondents remembered positive things, had wonderful memories and had not forgotten their spa experiences. The level of quality customer service and, more specifically, quality existing with facilities and treatments are the determinants that affect whether a spa consumer is to return or not.

Limitations

Limitations are the lines in the sand that remind us of our human boundaries, but they also serve as the canvas on which we paint the colours of creativity and innovation.

Response Rate

Regarding age, no one in the last two age groups (61-70 and 70+) participated in the questionnaire. Although many spa consumers are of this age, an online e-survey may not be the best way to target or gain their interest in this study. Using an online e-survey failed to capture people aged both 61-70 and 70 onwards. This may be due to not personally knowing people of this age to distribute the survey through snowball sampling. In addition, most people in these age categories may not have access to the internet or are not IT literate to use the internet to the best of their abilities. They may be suffering from physical incapability or health condition that prevents them from daily activities. A better approach to collecting data from ageing populations is best made by having paper questionnaires that are either hand-delivered or done face-to-face (Fryrear, 2016). However, the original idea for the study may have captured these age groups better as it would have used paper questionnaires and included face-to-face interaction. Although nobody from these age groups responded to the survey, the response rate was not detrimentally impacted and provided a broad spectrum of ages.

Obstacles

The challenges of collecting data during a global pandemic (coronavirus) raising unpredicted times of uncertainty are restricting for a researcher and resulted in the original methodology being implemented. Due to closed spas and self-isolation regulations, the best course of action was to shift the questionnaire online. No further interviews could be conducted with a spa

manager. Therefore, this affected the collected data as it does not specifically answer the study's aim and main objectives (client retention and what builds consumer loyalty) from a direct professional within the spa industry. However, the authenticity of the findings may have been influenced from the spa consumer perspective as it provides insight into the motivations, the amenities needed to create memorable spa experiences, and the services and provisions needed from the spa operators that contribute towards generating client retention.

Time

The timeframe in which to run the collection of data was constricting as the questionnaire survey was distributed online on Friday 20th of March and was closed on the 3rd of April. This only allowed two weeks to collect data, insufficient time to generate a high response rate. Nevertheless, by implementing a specific timeframe, the research was organized in a way that helped to benefit the time needed to discuss further the data collected.

Question Structure

Suppose I had the chance to repeat this study. In that case, it is possibly worth rethinking the question “What was memorable about your most recent spa experience?” as it did not achieve a difference in responses other than the fact that it was based on recent events and not any past experiences. This question could be replaced with something that directly asks, “What are your motivations for consuming spa?” as this

may have successfully provided answers that meet the objective of exploring the motivations of spa consumers. However, this may be perceived as an intrusive and personal question if asked directly.

Conclusion

This study explored how memorable spa experiences are created alongside considerations of client retention and consumer loyalty from a spa consumer perspective. It filled the gaps in the existing literature within the spa industry (Lo et al. 2015; Loureiro et al. 2013; Mak et al. 2009), including customer loyalty, guest satisfaction, and the development of memorable spa experiences. It generated personal views and opinions based on prior and recent experiences in a spa setting, focusing on hotel and destination experiences. However, respondents may have answered that they only had a day spa experience.

Objective one was to explore the motivations of spa consumers by inviting respondents to give descriptions of personal spa experiences that they deem to be memorable and address the expectations of spa experiences to discover client preferences and the emotions or feelings that need to occur when visiting a spa for them to feel satisfied with their spa journey. In doing this, it found that relaxation is the driving motivation behind going to the spa, along with other feelings of authenticity and thoughts of “being treated well” by employees. Primary research findings complement previous studies by Mandelbaum and Lerner (2008) on the contemporary spa consumer, Mak et al. (2009) about relaxation and rejuvenation as the prevalent motivational factors. Tourism literature from Chen et al. (2008) further supports regard relaxation being the primary trend for memorable spa experiences acting as a key motivator for experiencing wellness, and Hu et al. (2019) on the capabilities of the contemporary spa consumer by identifying a spa they intend to visit based on value and quality.

However, it contradicts Sipe and Testa’s (2018) findings as escapism was not the main expectation of a spa experience; findings show that there is now a focus on the feelings of being in a high-standard luxurious environment followed by less common themes around cleanliness, cost, and happiness. Whilst the study finds this, perhaps a different question that focuses on the specific spa consumers' reasonings for seeking a spa experience, a few responses explained what motivated them to go and book or visit a spa in particular. The study approaches the investigation from a spa operator's point of view and, for this reason, could be the background to assist existing or new spas in designing innovative spas that engage and entice spa consumers to become repeat guests.