Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Hospitality and Tourism Industry

June 2, 2022

Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility in Tourism

June 2, 2022Consumer behaviour and ethnocentrism drive preferences for Hoizäme, the Swiss-labeled outdoor wear company, reflecting a blend of fashion choices, cultural identity, and trust in product quality. In fashion, Hoizäme, the Swiss-labeled outdoor wear company, commands attention not merely for its functional and stylish designs but for the intriguing interplay between consumer behaviour and ethnocentrism. The brand has artfully woven these elements into the fabric of its identity, creating a distinctive narrative that goes beyond fashion choices. This blog explores the captivating dynamics that underpin consumer decisions, unravelling the threads of cultural connection intricately woven into the Hoizäme brand.

Influence of Social Networks on Online Purchasing Behavior of Consumers

Hoizäme's allure lies in its aesthetically pleasing designs and ability to tap into consumers' psychological and cultural behaviours. By aligning itself with Swiss values and craftsmanship, the brand has created a unique identity that resonates with consumers seeking more than just clothing. The symbiotic relationship between consumer choices and ethnocentrism unfolds as Hoizäme becomes a symbol not just of outdoor fashion but of Swiss heritage and excellence.

Literature Review

The literature review is the intellectual heartbeat of scholarly exploration, where the rhythm of past research sets the tempo for new investigations. It functions as a literary kaleidoscope, refracting the diverse perspectives and methodologies that have shaped a particular academic domain. Much like a detective meticulously assembling clues, researchers scour the pages of existing literature to unveil patterns, gaps, and insights. It is the foundation for new ideas, providing a roadmap for understanding a specific field's context, challenges, and advancements. The literature review is, therefore, not just a mere overview but a dynamic dialogue between past and present scholarship, offering a nuanced understanding of the ongoing conversation in academia.

Chapter Overview

Over the past six decades, extensive theoretical and empirical research has scrutinized consumer decision-making and brand characteristics. Factors like experience, expert opinions, reputation, and others play a pivotal role in shaping consumer behaviour, particularly in the complex realm of fashion. The decision-making process is further complicated by the deluge of product and brand information, including subliminal marketing tactics through various television, radio, social media, and celebrity endorsements. These strategies significantly impact consumers' brand awareness, influencing brand image and equity and fostering associations with specific brands and products.

Assessing the Impact of Digital Marketing in Generating a High Customer Base of Online Retailers

A deeper examination reveals that intrinsic and extrinsic cues are integral to consumer decision-making. Intrinsic cues encompass physical product characteristics, like quality or performance, which can only be assessed post-purchase. On the other hand, extrinsic cues include non-direct product attributes such as brand, price, retailer influence, and reputation. While extrinsic cues may not directly impact a product's performance, they shape consumer opinions regarding product quality, particularly for less-known foreign products.

The cognitive influence of the country of origin (COO) as an extrinsic cue also plays a crucial role in shaping consumer beliefs about product quality. Price is a significant factor, as consumers with limited product knowledge often form opinions based on the perceived relationship between price and quality. This relationship is influenced by the depiction of lower prices corresponding to lower quality and vice versa. The connection between the COO and a product is closely tied to consumers' perceptions of that country and their evaluation of the associated product.

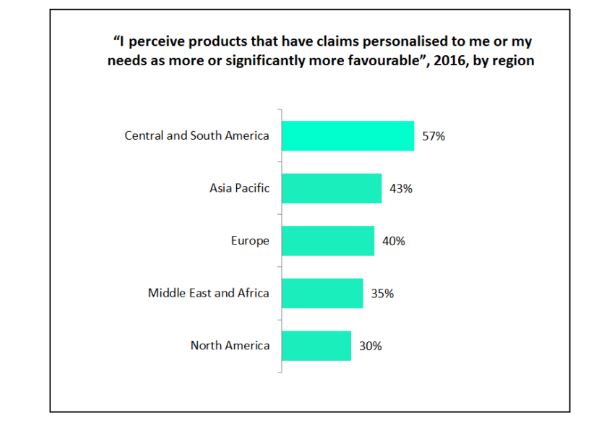

Moreover, cognitive behaviour, influenced by personal experiences, exposure, or affinity toward a particular country of origin, contributes to the decision-making process. Ethnocentric beliefs regarding the consumption of international products may vary across regions, as highlighted by Fernández-Ferrín et al. (2018). Despite these influences, contemporary consumers are increasingly interested in purchasing products tailored to their needs, irrespective of their pre-existing beliefs, as depicted in Figure 1.

Karoui and Khemakhem (2019) emphasized the significant role that government authorities in countries can play in enhancing the revenues of international companies. This sentiment was echoed by Mostafa, Al-Mutawa, and Al-Hamdi (2019), who concurred and suggested that extensive advertising campaigns promoting local products could be curtailed, thereby allowing opportunities for international entities.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework serves as the conceptual foundation for research, guiding scholars through the landscape of ideas relevant to their study. It acts as a dynamic lens, shaping the interpretation of data and providing the intellectual structure for the research endeavour. This framework is not just a static backdrop but an evolving framework that adapts to new insights, contributing a unique perspective to the broader body of knowledge.

Types of Impulse Buying

While most customers make unplanned decisions when purchasing a product, this theoretical framework focuses on impulse buying. Impulse buying is characterized by the spontaneous and arbitrary decisions made by customers. However, the various types of this purchasing phenomenon are influenced by different factors that contribute to such decisions, as elaborated below:

Hawkins-Stern Impulse Buying

According to Klasić's (2019) insights, the Hawkins-Stern impulse theory attributes consumer buying behaviour to impulsive tendencies. The theory posits that impulse buying can be categorized into four distinct types, each associated with specific impulses.

Pure Impulse Buying

According to the research conducted by Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić (2018), one form of impulse buying involves consumers making unplanned purchases purely driven by impulsive urges. In this type of buying, the specific item is not premeditated in the buyer's thoughts. Instead, certain attributes of the product captivate the customer, compelling them to make the purchase (Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić, 2018). According to Kumar (2020), Swiss products, known for their allure, frequently prompt customers to buy impulsively.

Reminder impulse Buying

According to the findings presented by Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić (2018), this particular form of impulse behaviour occurs when a buyer comes across a product and is reminded of the positive experiences they had with it or receives prior recommendations from friends or family. The buyer then decides to make a purchase based on the lingering effects of impulse buying (Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić, 2018). Similarly, as highlighted by Kumar (2020), when individuals spot a Swiss label in the market, it often triggers recollections of the satisfaction it brings to their peers. Consequently, they are inclined to impulse buy Swiss items as part of reminder impulse behaviour.

Suggested Impulse Buying

Likewise, as indicated by Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić (2018), this form of impulse arises through the marketing and advertising efforts associated with a product. When individuals encounter such products on television, social media, or other platforms, they experience an impulse to purchase the product, driven by the perceived benefits it can offer them (Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić, 2018). Elaborating on this, Kumar (2020) points out that Swiss products featured in advertising across television, social media, websites, and various platforms tend to stimulate impulse buying among the audience.

Planned Impulse Buying

Expanding on the insights provided by Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić (2018), this type of impulse emerges when an individual needs a product but is uncertain about which brand to choose. Consumers often opt for products that offer additional value, and this value is frequently associated with monetary benefits, such as lower prices or additional quantity (Vojvodić, Šošić, and Žugić, 2018). However, according to Kumar (2020), purchasing Swiss-labeled products does not align with planned impulse buying, as the value derived from these products is not primarily linked to financial savings but rather to the satisfaction derived from their quality.

Theories Associated with Rationale Buying

Theories associated with rational buying often emphasize systematic decision-making processes, where consumers carefully assess product attributes, compare options, and make informed choices based on logical reasoning. Models such as the Economic Man Theory and the Consumer Decision-Making Model delve into the rational aspects of purchasing behaviour, emphasizing factors like utility, cost-benefit analysis, and information processing in the decision-making process.

Theory of Reasoned Action

In Klasić's (2019) study, the theory of reasoned action is delineated as centred on individuals making informed decisions, where actions are taken with anticipation of the expected outcomes. Expanding on this in the context of consumer behaviour, Otieno et al. (2016) elaborate that the theory posits consumers engage in rational purchasing behaviour, with their decisions influenced by the anticipated benefits of the product. Paul, Modi, and Patel (2016) concur, emphasizing that the theory underscores consumers' intentions as pivotal factors shaping their decision to purchase a product. This intentional decision-making is evident in Swiss products, where consumers deliberately buy Swiss items, fully aware of the associated costs and expected benefits.

Holistic Brand Theory

Pharr (2005) introduced a comprehensive Country of Origin (COO) model that incorporates holistic brand theory, asserting that a brand's image moderates the COO's impact on perceived product quality. This model considers various influences, including consumers' holistic perceptions of COO beliefs, such as the country's image (Pharr, 2005). However, counterarguments challenge this model, suggesting consumer behaviour and perception shifts within the fashion industry. Extrinsic cues like brand trust, rather than the COO of production, now significantly influence decision-making, as observed in the preference for considering the country of the brand over the COO of production (Haefner et al., 2011). Magnusson et al. (2014) question the evidential support for the role of COO in consumers' product decision-making, proposing a conceptual framework acknowledging biases where "product-level beliefs affect country-level beliefs." Biases, particularly favouring products from developed countries, negatively impact those from less developed countries with a lower COO image (Kotler and Gertner, 2002). Watson and Wright (2000) note that consumers from less developed countries often prioritize products from developed countries. Steenkamp (1990) adds that consumers' COO image is shaped by prior knowledge, exposure, and disposition, leading to stereotyped COO images irrespective of product quality (Wasswa, 2017). Kaynak et al. (2000) argue that moral considerations, such as child labour or fair trade practices, associated with less developed COOs influence consumer purchase behaviour. Hence, consumers' purchase behaviours and decision-making cues are diverse, involving the COO and country image, other environmental factors, and personal beliefs.

Comprehending Consumer Behaviour

Factors of Consumer Behaviour Influencing Purchasing Decisions

Various factors shape consumer purchasing behaviour, including personal preferences, social influences, cultural backgrounds, economic considerations, and marketing strategies. Understanding these influences is crucial for businesses seeking to tailor their products and marketing approaches to meet consumers' diverse needs and motivations.

Need determination

Bekoglu, Ergen, and Inci (2016) assert that the consumer consumption model underscores the decision to consume may not solely arise from brand promotions or marketing efforts but rather from a self-identified need. Liu and Mattila (2017) concur, noting that although advertising may initiate such decisions, it is inaccurate to assume that all choices stem from this origin. Esposito (2019) adds that the self-identification of a need is a comprehensive process susceptible to consumer biases, ultimately shaping the purchase decision.

Information Search

Once consumers identify a need, they gather information about available products (Bilgihan, Kandampully, and Zhang, 2016). This process is straightforward in cases where consumers have encountered advertisements or sought recommendations. Park and Lee (2017) note that while some consumers explore options through various channels, focusing on the search process is more practical due to its predictability.

Companies leverage consumers' past sales and visitation patterns in the intensively competitive SEO landscape to attract attention to product pages and websites (Elberg et al., 2019). Kamboj and Rahman (2017) consider the educational content on a company's website, detailing product usage and benefits, as a strategic approach to influencing consumer behaviour. Mahmood and Sismeiro (2017) counter this perspective, asserting that consumers are likelier to engage with and consume products from such informative websites.

Pre-Shopping Assessment

When the product data has been searched, the consumers start the pre-buying assessment (Faulds et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2018) agreed and stated that this may be done through perusing item audits, contrasting with different items, or considering individual factors, for example, cost. According to Soni and Verghese (2018), providing various choices for buyers is enticing today. However, Abou-Shouk and Khalifa (2017) argued that there is a need to understand that an excess of decisions can discourage a purchaser from buying a product.

Purchase

The consumption stage is the one that most intently identifies the consumption decision model, with the sole activity simply being consumption (Barnes and Mattsson, 2016). Similarly, as with the pre-consumption stage, this considers the components that carried the client to this point. Van Weelden, Mugge, and Bakker (2016) agreed and stated that there is a need to apply a seamless transaction to complete the consumption process.

Post-Consumption Assessment

According to Xu and Chen (2017), the post-shopping assessment will decide if a shopper purchases from the company later. While a lot of this choice may lie with the exhibition of the item itself, the job of the post-assessment of the product must not be considered insignificant (Kumar, Vohra, and Dangi, 2017). Offering help with an item is one of the most proficient methods to positively influence the consumer’s behaviour, affecting the buyer’s decision on future purchases (Filieri et al., 2018).

Comprehending the Ethnocentric Beliefs

Zalega (2017) stated that ethnocentric beliefs entered the field of business when they had been proposed as one of the potential factors that can impact a consumer’s decision. Han and Guo (2018) added that it has been considered a human characteristic that can impact purchaser decisions in differing buying circumstances. Zeren, Kara, and Arango (2020) defined ethnocentric beliefs as one of the variables that can influence the buyer's choice of whether to purchase an item, domestically or internationally produced. Likewise, Le et al. (2017) elaborated on this concept as a variable that straightforwardly impacts the customer's eagerness to buy foreign items. Jiménez-Guerrero, Pérez-Mesa, and Galdeano-Gómez (2020), however, argued and stated that purchaser ethnocentric beliefs demonstrate a general tendency of purchasers to evade every single imported item regardless of cost or quality contemplations because of nationalistic reasons. Due to this explanation, the idea of ethnocentrism is unmistakably significant in global promotion and is a potential obstacle for organizations expecting to infiltrate international markets. Piligrimienė and Kazakauskiene (2016) stated that ethnocentric beliefs are viewed as one of the radical hindrances restricting globalization. According to Qing, Lobo, and Chongguang (2012), ethnocentrism is an inescapable phenomenon in exceptionally industrialized nations. Studies conducted on this concept, such as (Watson and Wright, 2000 Torres and Gutiérrez, 2007 Karoui and Khemakhem, 2019), normally show that ethnocentric purchasers pick domestic items over foreign ones (Pasrija and Bhattacharjee, 2019). Generally, the beliefs of ethnocentrism speak to the widespread liking for individuals to see their environment as the focal point of the universe and to decipher other social units from the viewpoint of their gathering. Such people dismiss others who are socially unique while aimlessly tolerating the individuals who are socially parallel to themselves. Ethnocentric belief is the opinions buyers hold about the suitability and the ethical quality of products made internationally.

Website Attributes on Consumer Buying Pattern

Zhang (1997) argues that the ethnic background of consumers influences attitudes and behaviours in the decision-making process of foreign products. However, further research from Piron (2002) discarded this theory, stating that there was no evidence that ethnic background or race impacts consumer ethnicism. (Javalgi et al., 2005) found that more educated consumers in higher income brackets and social classes are less inclined to have ethnic tendencies and prejudices. With the option of worldwide travel, they are open to foreign markets and products (Samiee et al., 2005). Hence, social class influences the values and beliefs of consumers, which impact the purchase decision-making process when purchasing domestic and foreign products. Coleman (1983) claims that higher social class consumers are more inclined to purchase brand products directly associated with their social class. Shimp and Sharma (1987) agree that ethnocentric tendencies tend to be seen in working-class consumers with lower incomes, but this diminishes the higher the consumer climbs the social ladder. However, again, further studies purport this to be inaccurate and disregard the relationship between higher earners and consumer ethnicism (Han and Terpstra, 1988). The Caruana (1996) study showed no evidence of class differences in consumers’ ethnocentrism.

Dependence of Consumer Purchase Decision on Ethnocentric Beliefs

The Halo effect model identifies that a country`s image affects consumers' decision-making process in product quality and performance evaluation. Thus, the COO is not solely a cognitive cue because it directly affects consumers' decision-making process (Bloemer et al., 2009). However, this model is weak for it is purely reliant on the consumer's product perception, based on the country's image and doesn’t consider whether there is prior product information or brand knowledge from such country (Xu, 2010) as opposed to the summary effect whereby consumers are aware of the COO and product to form their country image and perceptions through their knowledge and experience with the product (Bloemer et al., 2009) García-de-Frutos and Ortega-Egea, (2015) emphasise the importance of COO in the cognitive decision-making process depending on the disposition of the consumer towards specific products/brands concerning geographical backgrounds country association and beliefs. Moreover, such associations and beliefs may lead to COO bias. For example, a British-born Indian consumer may favour Indian silk over Chinese silk due to the association or attachment with the country and not necessarily because of the quality of the silk. Therefore, consumer attitude toward a specific country shapes their opinion (Obermiller and Spangenberg, 1989), especially if the country maintains a symbolic and emotional connection with the consumer (Steenkamp, 1990). The COO image influences the consumer’s quality perception and positively or negatively affects the decision-making process, dependent on the value bias of the consumer (Maher and Carter, 2011). For example, clothing brands are perceived as more prestigious in the fashion industry and carry more status when connected to high-quality fashion-orientated countries, such as France and Italy. Audita and Marck (2017) claim that such a purchase decision is based on pride in owning prestigious products from specific fashion-labelled countries. This indicates that consumers' purchasing behaviour towards the COO image directly influences decision-making.

Loyalty Program in Building Customer Loyalty within Grocery Retailing Setting

There are mixed findings on gender-specific segmentation of consumer ethnocentrism (Han and Terpstra, 1988). Good and Huddleston (1995) imply that women have greater ethnocentric tendencies because they are more patriotic and less likely to purchase foreign products. Han and Terpstra (1988) support this notion by stating that women are perceived to be more ethnocentric because they are seen to be more conservative. However, studies by (Caruana 1996) discard this notion since no gender differences were apparent. However, Bannister and Saunders (1978) state that their findings purport men to be more ethnocentric. This is an area that requires more research.

Product Labelling by Different Countries

Developing countries' organisational and product innovation allows mass-produced products and lower labour costs (Yang et al., 2015). Clothing products produced in such developing countries significantly reduce costs due to the engagement of low-cost manufacturers (Bulut and Lane, (2011). Products are then packaged and distributed from a European country, such as Germany and consequently labelled `Made in Germany`, with the prestige of German products/brands. For example, the well-known German brands PUMA and Adidas have been strong sportswear and shoe brands since the two German brothers Rudi and Adi Dassler separated their joint company Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik and set up into competition. Both companies have their registered brands and headquarters in Bavaria, Germany, but manufacture products in Latin America, Greater China and Asia, among others (Hoover, 2020). Installing production innovation of mass-produced products and lower labour costs (Yang et al., 2015). However, both companies distribute products to over 120 countries worldwide, with the prestige of German-made brands. Driving the consumer COO quality judgement on brand rather than product (Miranda, 2017). The EU regulations state that only 60% of the product production needs to take place in the COO to be labelled accordingly. USA labelling differs to allow consumers to make presumptions about the quality and value of the products. Globalisation allows clothing manufacturers to source raw materials from several countries, making it difficult to identify one COO (Wasswa, 2017). Therefore, where the COO and country of production differ, consumers base their cognitive purchase decision on the brand image. That said, the perceived decision-making process of fashion products, brands and country of purchase is personal. It differs due to consumers' nationality, age, gender, status and lifestyle, even when evaluating the same product (Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2004).

On the other hand, Shimp et al. (2005) highlight that patriotic consumers with high ethnocentrism only support their own country and, where possible, avoid purchasing foreign products. These consumers are proud of products developed in their own country and hold them in higher regard than those from foreign countries, irrespective of products superiority and consider the added benefit of contributing to their economy (Shimp et al., 2005) That said, they are not hostile to other countries and patriotism should not be mistaken for nationalism, whereby the belief is that their country and products are superior to those of other countries (Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2008) Therefore, remaining judgemental about products from countries which differ to their own (Zhang, 1997) which may cause objects of contempt to foreign products (Manzoor and Shaikh, 2016). Schiffman and Kanuk (2012) analysed the COO effect and consumer ethnocentrism and how these factors impact consumers' behaviour and decision-making. Products with “Made in” labels specifying the COO permit consumers to make purchasing decisions based on the specified country. Furthermore, Nagashima (1977) states that products from France are considered prestigious and luxurious. French consumers with strong ethnocentric beliefs about their own country would be willing to pay more for `Made in France` labelled products due to national pride and patriotism. Chao (1998) also remarks that this belief is predominately a favourable disposition of consumers from more developed countries.

Exploring the Swiss Business Market: Insights into the World of Swiss-Labeled Fashion

Swiss Label (2020b) states that the Swill label is Switzerland's national marketing strategy, and the country aims to develop itself as an industrial hub. Further elaborated by Swiss Label (2020a), the Swill Label aims to support the Swiss economy by leading in different product categories at home and abroad. The Swiss label is defined by the quality of its products and services (Swiss Label, 2020a). As Schweizer Jass (2020) explained, Swiss labels' main selling point is the quality of Swiss products. Swiss products are of high quality and design and aim to attract customers and last long (Schweizer Jass, 2020). According to Först (2020), to make Switzerland an industrial hub, the Swiss business Hub is developed across different countries to make people aware of Swiss quality and further enhance the profits of Swiss products. Further explained by FDFA (2020), the Swiss business hubs are operated under the support of the Swiss government. They aim to support different SMEs in Switzerland in exporting their products beyond Switzerland and expanding their businesses in the international market.

Abegg (2018) states that the products made under the Swiss label enjoy the reputation of being quality products worldwide. Consumers from different countries commonly perceive Swiss products as expensive but high quality, which cancels out the expense factor (Abegg, 2018). According to Allen (2008), Switzerland has been reputable for its quality watches, efficient banks, and luxurious hotels throughout the markets it entered. However, it is argued that their products are not innovative and lack in the IT field (Allen, 2008). As per the study by Sullivan (2020), it has been identified that a brand label can be used to create a positive perception in the minds of consumers. According to Kim, Lloyd and Cervellon (2016), a brand label tends to portray quality, which is the essential selling point of the product or service. Consumers purchase Swiss products for a similar reason: they perceive them to be high quality. Another reason the consumers purchase Swiss products or any other high-end brand, as explained by Yeh, Wand and Yieh (2016), is due to the increase in value they receive by consuming such high-end, high-quality products.

Literature Gap

Numerous studies on consumer behaviour, such as those (De Mooij, 2019; Gkaintatzis et al., 2019; Mandel et al., 2017), have been initiated in the past to identify the need to understand consumer behaviour in different industries. However, a lack of understanding of the role of consumer behaviour has been observed in the clothing industry. According to Koszewska (2016), consumers’ behaviour towards apparel shopping significantly and positively influences their willingness to pay a product premium. This identifies the significance of the role of consumer behaviour in the clothing industry and the need to understand the methods to influence consumer decisions regarding the purchase of premium-labelled products that are not yet met. This study aims to meet this need and provide a better understanding of the role of consumer behaviour in the decision to consume exceptional products such as Swiss-labelled outdoor wear.

Chapter Summary

Many consumer behaviour factors influence the decision-making process that enables consumers to buy Swiss items. The decision-making process of Swiss products begins with the identification of the need that the consumer wants to fulfil. The consumer then gathers information regarding the Swiss products he/she requires. The consumer then purchases the Swiss product after assessing the market regarding the product. After purchasing the product, the consumer evaluates the experience he/she received from the Swiss-labelled product. Among the many factors influencing the decision-making products, one such factor is the country’s image. Swiss people are attracted to their country; thus, they purchase products that support their country's economy. The ethnocentric beliefs of Swiss people play a factor in influencing their decisions. Swiss products are valued for their quality around the world; thus, products with Swiss labels also play a factor in influencing consumer behaviour.

Theoretically, purchasing Swiss-labelled products can be explained using the Hawkins-Stern impulse theory and the theory of reasoned action. As per Haskins-Stern, a consumer's buying decision is based on his/her different impulses; thus, there are different types of impulses, such as pure, reminder, suggested, and planned. However, the theory of reasoned action explains that the decision to purchase a Swiss-labelled product is rational and as per the consumer's will.

Explore HND Business and Marketing Strategy

The Swiss label has been established worldwide; these products' selling point is their quality and the value they add to the consumer. The Swiss government aims to make itself the industrial hub and thus has created Swiss business hubs in several countries. With these business hubs, the Swiss government supports its SMEs in exporting products and expanding to different countries.

References

Abegg, B., 2018. The Geographical Trade Mark: A Swiss Innovation Worth Copying? IIC-International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 49(5), 565-590.

Abou-Shouk, M.A. and Khalifa, G.S., 2017. The influence of website quality dimensions on e-purchasing behaviour and e-loyalty: a comparative study of Egyptian travel agents and hotels. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), pp.608-623.

Allen, M., 2008. Swiss brand still stands for quality. Retrieved 7 April 2020, from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/swiss-brand-still-stands-for-quality/6742400

Audita, H., and Marck, M., 2017. Cross Cultural Consumers Perceptions of Country-of-Origin and Luxury Brands. Jurnal Akuntansi, Manajemen dan Ekonomi, 19(1), pp.11–18. http://jos.unsoed.ac.id/index.php/jame/article/view/950/698

Audita, H., and Marck, M., 2017. Cross Cultural Consumers Perceptions of Country-of-Origin and Luxury Brands. Jurnal Akuntansi, Manajemen dan Ekonomi, 19(1), pp.11–18. http://jos.unsoed.ac.id/index.php/jame/article/view/950/698

Balabanis, G., and Diamantopoulos, A., 2004. Domestic country bias, country-of-origin effects, and consumer ethnocentrism: A multidimensional unfolding approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(1), 80-95. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/224899776?accountid=8058

Balabanis, G., and Diamantopoulos, A., 2008, ‘Brand Origin Identification by Consumers: A Classification Perspective’, Journal of International Marketing, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 39–71, <http://search.ebscohost.com.salford.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib,cookie,ip,url,uid&db=buh&AN=28839949>.

Bannister, J.P. and Saunders, J.A., 1978. UK Consumers' Attitudes towards Imports: The Measurement of National Stereotype Image. European Journal of Marketing, 12(8), pp.562–570. https://www-emerald-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EUM0000000004982/full/html

Barnes, S.J. and Mattsson, J., 2016. Understanding current and future issues in collaborative consumption: A four-stage Delphi study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 104, pp.200-211.

Bekoglu, F.B., Ergen, A. and Inci, B., 2016. The impact of attitude, Consumer innovativeness and interpersonal influence on functional food consumption. International Business Research, 9(4), pp.79-87.

Bilgihan, A., Kandampully, J. and Zhang, T.C., 2016. Towards a unified customer experience in online shopping environments. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences.

Bloemer, J., Brijs, K., and Kasper, H. 2009, "The CoO-ELM model: A theoretical framework for the cognitive processes underlying country of origin-effects", European Journal of Marketing, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 62-89. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/237030102?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo#

Bloemer, J., Brijs, K., and Kasper, H., 2009, "The CoO-ELM model: A theoretical framework for the cognitive processes underlying country of origin-effects", European Journal of Marketing, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 62-89. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/237030102?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo#

Broniarczyk, S., M. and Alba, J., W., 1994. The Role of Consumers' Intuitions in Inference Making. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(3), pp.393–407. https://sal-primo-production.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_gale_ofa62197108&context=PC&vid=SAL_MAIN&lang=en_US&search_scope=LSCOP_SAL&adaptor=primo_central_multiple_fe&tab=all&query=any,contains,Broniarczyk%20&%20Alba%201994&offset=0

Bulut, T., and Lane, C., 2011. The Private Regulation of Labour Standards and Rights in the Global Clothing Industry: An Evaluation of Its Effectiveness in Two Developing Countries. New Political Economy, 16(1), pp.41–71. https://www-tandfonline-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1080/13563460903452579

Caruana, A. 1996. The effects of dogmatism and social class variables on consumer ethnocentrism in Malta. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 14(4), 39-44. doi:http://dx.doi.org.salford.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/02634509610121569

Chao, P., 1998. Impact of Country-of-Origin Dimensions on Product Quality and Design Quality Perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 42(1), pp.1–6. https://www-sciencedirect-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S014829639700129X

Coleman, R., 1983. The Continuing Significance of Social Class to Marketing. Journal of Consumer Research (pre-1986), 10(3), pp.265–280. http://sal-primo-production.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/bntvdo/TN_proquest223325750

De Mooij, M., 2019. Consumer behaviour and culture: Consequences for global marketing and advertising. SAGE Publications Limited.

Ebaertsch, B., Ejaeger, M., Ekawohl, W., Enordt, C., Erössler, W., Eviering, S., and Ewarnke I., 2015. Supported employment for the reintegration of disability pensioners with mental illnesses: a randomised controlled trial. Frontiers in Public Health, 3, p.237. https://doaj.org/article/4626b050e6cc43c9ba5788b998e9e792

Elberg, A., Gardete, P.M., Macera, R. and Noton, C., 2019. Dynamic effects of price promotions: Field evidence, consumer search, and supply-side implications. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 17(1), pp.1-58.

Esposito, M., 2019. Consumer behaviour and corporate strategies in the decision journey: active vs passive consumers.

Faulds, D.J., Mangold, W.G., Raju, P.S. and Valsalan, S., 2018. The mobile shopping revolution: Redefining the consumer decision process. Business Horizons, 61(2), pp.323-338.

FDFA., 2020. Swiss Business Hub. https://www.eda.admin.ch/countries/canada/en/home/switzerland-and/export-promotion/swiss-business-hub.html

Fernández-Ferrín, P., Calvo-Turrientes, A., Bande, B., Artaraz-Miñón, M. and Galán-Ladero, M.M., 2018. The valuation and purchase of food products that combine local, regional and traditional features: The influence of consumer ethnocentrism. Food Quality and Preference, 64, pp.138-147.

Filieri, R., McLeay, F., Tsui, B. and Lin, Z., 2018. Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Information & Management, 55(8), pp.956-970.

Floren, J., Rasul, T. and Gani, A., 2019. Islamic marketing and consumer behaviour: a systematic literature review. Journal of Islamic Marketing.

Först, T., 2020. Swiss Business Hubs. https://www.s-ge.com/en/swiss-business-hubs

Funk, D., Funk, D.C., Alexandris, K. and McDonald, H., 2016. Sport consumer behaviour: Marketing strategies. Routledge.

García-de-Frutos, N., and Ortega-Egea, J., M., 2015. An Integrative Model of Consumers’ Reluctance to Buy Foreign Products: Do Social and Environmental Country Images Play a Role? Journal of Macromarketing, 35(2), pp.167–186. https://journals-sagepub-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1177/0276146714546749

Gkaintatzis, A., Constantinides, E., Karantinou, K. and van der Lubbe, R., 2019, May. The effect of music on consumer behaviour: A neuromarketing approach. In 27th Annual High Technology Small Firms Conference, HTSF 2019.

GlobalData Report Store, 2020. You Searched For - Globaldata Report Store. [online] GlobalData Report Store. Available at: <https://store.globaldata.com/search/consumer/?s=> [Accessed 7 April 2020].

Good, L., K., and Huddleston, P., 1995. Ethnocentrism of Polish and Russian consumers: are feelings and intentions related? International Marketing Review, 12(5), pp.35–48. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/224321424/fulltextPDF/6BEDC11689E54A9BPQ/1?accountid=8058#

Haefner, J. E., Deli-Gray, Z., and Rosenbloom, A. 2011. The Importance of Brand Liking and Brand Trust in Consumer Decision Making: Insights from Bulgarian and Hungarian Consumers. During the Global Economic Crisis. Managing Global Transitions: International Research Journal, 9(3). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=de&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=The+Importance+of+Brand+Liking+and+Brand+Trust+in+Consumer+Decision+Making%3A&btnG

Han, C. and Terpstra, V., 1988. Country-Of-Origin Effects For Uni-National And Bi-National. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(2), pp.235–255. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/197153111?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Han, C.M. and Guo, C., 2018. How consumer ethnocentrism (CET), ethnocentric marketing, and consumer individualism affect ethnocentric behaviour in China. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(5), pp.324-338.

Hartmann, C. and Siegrist, M., 2017. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 61, pp.11-25.

Herzberg, H., Ketty, H.M., Orozco-Acosta, E., and Visbal, O., 2017. "The influence of country of origin cues on product evaluation: evidence from Swiss and German consumers." Journal of technology management & innovation 12.2: 18-25. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?as_ylo=2016&q=swiss+made+label&hl=de&as_sdt=0,5

Javalgi, R., G., Khare, V., P., Gross, A., C., and Scherer, R., F., 2005. An application of the consumer ethnocentrism model to French consumers. International Business Review, 14(3), pp.325–344. https://www-sciencedirect-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0969593104001295

Jiménez-Guerrero, J.F., Pérez-Mesa, J.C. and Galdeano-Gómez, E., 2020. Alternative Proposals to Measure Consumer Ethnocentric Behavior: A Narrative Literature Review. Sustainability, 12(6), p.2216.

Jung, H.S., Seo, K.H., Lee, S.B. and Yoon, H.H., 2018. Corporate association as antecedents of consumer behaviours: The dynamics of trust within and between industries. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, pp.30-38.

Just, D.R. and Byrne, A.T., 2020. Evidence-based policy and food consumer behaviour: how empirical challenges shape the evidence. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 47(1), pp.348-370.

Kamboj, S. and Rahman, Z., 2017. Measuring customer social participation in online travel communities. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology.

Karoui, S. and Khemakhem, R., 2019. Consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 25(2), pp.63-71.

Kaynak, E., Kucukemiroglu, O., and Hyder, A., S., 2000. Consumers’ country‐of‐origin (COO) perceptions of imported products in a homogenous, less‐developed country. European Journal of Marketing. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Erdener_Kaynak/publication/242020362_Consumers'_country-of-origin_COO_perceptions_of_imported_products_in_a_homogenous_less-developed_country/links/5852ff9b08ae7d33e01ab41d/Consumers-country-of-origin-COO-perceptions-of-imported-products-in-a-homogenous-less-developed-country.pdf

Kim, J. E., Lloyd, S., and Cervellon, M. C., 2016. Narrative-transportation storylines in luxury brand advertising: Motivating consumer engagement. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 304-313.

Klasić, T., 2019. Four consumer behaviour theories every marketer should know and use. https://medium.com/digital-reflections/four-consumer-behavior-therioes-every-marketer-should-know-and-use-8b33ceb223b3

Koszewska, M., 2016. Understanding consumer behaviour in the sustainable clothing market: Model development and verification. In Green Fashion (pp. 43-94). Springer, Singapore.

Kotler, P., and Gertner, D., 2002, "Country as brand, product, and beyond A place marketing and brand management perspective", Journal of Brand Management, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 249-26. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/232486748?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Kumar, A., Vohra, A. and Dangi, H.K., 2017. Consumer decision‐making styles and post-purchase behaviour of poor for Fast Moving Consumer Goods. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(2), pp.121-137.

Kumar, I., 2020. Case Studies in Consumer Behaviour, 1e. https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=GSPKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15&dq=Swiss+label+case+studies&source=bl&ots=Uab5cbKfPz&sig=ACfU3U1KoHj5U909WpaUDPlaiHoWfR_h0Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj9xsaukNboAhW8QEEAHXc1DsAQ6AEwD3oECAwQJg#v=onepage&q=Swiss&f=false

Lampert, S., I., and Jaffe, E., D., 1998. A dynamic approach to country-of-origin effect. European Journal of Marketing, 32(1/2), pp.61–78. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/1839908890?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Langan, R., Besharat, A., and Varki, S., 2017. Review valence and variance affect product evaluations: Examining intrinsic and extrinsic cues. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(2), pp.414–429. https://www-sciencedirect-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0167811615300422

Le, H.T., Nguyen, P.V., Dinh, H.P. and Dang, C.N., 2017. Effects of country of origin and product features on customer purchase intention: A study of imported powder milk. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal.

Liu, S.Q. and Mattila, A.S., 2017. Airbnb: Online targeted advertising, sense of power, and consumer decisions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 60, pp.33-41.

Magnusson, P., Krishnan, V., Westjohn, S., A., and Zdravkovic, S., 2014. The Spillover Effects of Prototype Brand Transgressions on Country Image and Related Brands. Journal of International Marketing, 22(1), pp.21–38. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.salford.idm.oclc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=f51431d2-40da-4554-b3a8-280a5808602a%40sessionmgr103&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNoaWIsY29va2llLGlwLHVybCx1aWQ%3d#AN=97479320&db=buh

Maher, A., A., and Carter, L., L., 2011. The affective and cognitive components of country image. International Marketing Review, 28(6), pp.559–580. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/900913014?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Mahmood, A. and Sismeiro, C., 2017. Will they come, and will they stay? Online social networks and news consumption on external websites. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 37, pp.117-132.

Mandel, N., Rucker, D.D., Levav, J. and Galinsky, A.D., 2017. The compensatory consumer behaviour model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behaviour. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), pp.133-146.

Manzoor, A., A., L. and Shaikh, K., 2016. Country of Origin (COO) and its Impact on Consumer Purchase Decision of Foreign Products. Global Management Journal for Academic & Corporate Studies, 6(2), pp.70–89. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/1925690849?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Miranda, J., A., A., 2017. The country-of-origin effect and the international expansion of Spanish fashion companies, 1975–2015. Business History, pp.1–21. https://www-tandfonline-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1080/00076791.2017.1374370

Mostafa, M.M., Al-Mutawa, F.S. and Al-Hamdi, M.T., 2019. KUWAITI ATTITUDES TOWARDS ADAPTED PERFUME ADVERTISEMENTS: THE INFLUENCE OF COSMOPOLITANISM, RELIGIOSITY, ETHNOCENTRISM AND NATIONAL IDENTITY. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 24(1).

Nagashima, A., 1977. A COMPARATIVE 'MADE IN' PRODUCT IMAGE SURVEY AMONG JAPANESE BUSINESSMEN. Journal of Marketing, 41(3), pp.95–100. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/209272964/fulltextPDF/5FF626BB9B564AEAPQ/1?accountid=8058

O’Reilly, M., and Parker, N., 2013. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: a critical exploration of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative research, 13(2), pp.190-197. https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%27Unsatisfactory+Saturation%27%3A+a+critical+exploration+of+the+notion+of+saturated+sample+sizes+in+qualitative+research&btnG=

Obermiller, C., and Spangenberg, E., 1989. EXPLORING THE EFFECTS OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN LABELS - AN INFORMATION-PROCESSING FRAMEWORK. Advances In Consumer Research, 16, pp.454–459. http://web.a.ebscohost.com.salford.idm.oclc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=5158e4d2-536f-4c85-9df2-78bff4630ec1%40sdc-v-sessmgr03&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNoaWIsY29va2llLGlwLHVybCx1aWQ%3d#AN=6487747&db=buh

Otieno, O. C., Liyala, S., Odongo, B. C., and Abeka, S. O., 2016. Theory of reasoned action as an underpinning to technological innovation adoption studies.

Park, S. and Lee, D., 2017. An empirical study on consumer online shopping channel choice behaviour in an omni-channel environment. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), pp.1398-1407.

Pasrija, M.M. and Bhattacharjee, M., 2019. Consumption Propensity of Indian Shoppers with Special Reference to Ethnocentric Behaviour: A Study on Selected Goods and Services. research journal of social sciences, 10(6).

Paul, J., Modi, A., and Patel, J., 2016. Predicting green product consumption using the theory of planned behaviour and reasoned action. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 29, 123-134.

Pharr, J., M., 2005. Synthesizing Country-of-Origin Research from the Last Decade: Is the Concept Still Salient in an Era of Global Brands? Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(4), pp.34–45. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/212210670?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Piligrimienė, Ž. and Kazakauskienė, G., 2016. Relations Between Consumer Ethnocentrism, Cosmopolitanism and Materialism: Lithuanian Consumer Profile. In Business Challenges in the Changing Economic Landscape-Vol. 2 (pp. 231-242). Springer, Cham.

Piron, F., 2002. International out shopping and ethnocentrism. European Journal of Marketing, 36(1/2), pp.189–210. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/237025498?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Qing, P., Lobo, A. and Chongguang, L., 2012. The impact of lifestyle and ethnocentrism on consumers' purchase intentions of fresh fruit in China. Journal of Consumer Marketing.

Samiee, S., Shimp, T., A., and Sharma, S., 2005. Brand origin recognition accuracy: Its antecedents and consumers' cognitive limitations. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(4), 379. doi:http://dx.doi.org.salford.idm.oclc.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400145

Schiffman, L.G., Kanuk, L., L., and Hansen, Håvard, 2012. Consumer behaviour: a European outlook Second. pp.63-75. https://www-dawsonera-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/abstract/9780273724254

Schweizer Jass., 2020. Swiss Label - Schweizer Jass. https://schweizerjass.ch/en/swiss-label/

Shamim, M.A., Panhwar, I.A. and Iftikhar, S.F., 2019. Water Consumption Behavior: A Review with Global Perspective and Special Reference to Developing Country. Global Management Journal for Academic & Corporate Studies, 9(1), pp.146-162.

Shao, J., Taisch, M. and Mier, M.O., 2017. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: from the experts' viewpoints. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, pp.203-216.

Shimp, T. A., and Sharma, S., 1987. Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. JMR, Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 280. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/235210227?accountid=8058

Soni, N. and Verghese, M., 2018. Analyzing the impact of online brand trust on sales promotion and online buying decisions. IUP Journal of Marketing Management, 17(3), pp.7-24.

Steenkamp, J., B., E., 1990. Conceptual model of the quality perception process. Journal of Business Research, 21(4), pp.309-333. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/014829639090019A

Sullivan, F. C., 2020. How to Shape Your Brand’s Perception. Retrieved 7 April 2020, from https://medium.com/the-anatomy-of-marketing/how-to-shape-your-customers-perception-of-your-brand-2024e406ed60

Swiss Label., 2020a. What is SWISS LABEL? https://www.swisslabel.ch/en

Swiss Lable., 2020b. Vision / Mission. https://www.swisslabel.ch/en/swiss-label/vision-mission-3

Ting, S., C., 2012. HOW THE NEED FOR COGNITION MODERATES THE INFLUENCE OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN AND PRICE ON CONSUMER PERCEPTION OF QUALITY. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(4), pp.529–543. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/1022654733?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Torres, N.H.J. and Gutiérrez, S.S.M., 2007. The purchase of foreign products: the role of firm's country-of-origin reputation, consumer ethnocentrism, animosity and trust. Departamento de Economía y Administración de Empresas, Universidad de Valladolid.

Trinh, G., Romaniuk, J. and Tanusondjaja, A., 2016. Benchmarking buyer behaviour towards new brands. Marketing Letters, 27(4), pp.743-752.

Ulph, A., Panzone, L.A. and Hilton, D., 2017. A Dynamic Self-Regulation Model of Sustainable Consumer Behaviour. Available at SSRN 3112221.

Urbonavicius, S., Dikcius, V., and Navickaite, S., 2011. Country Image and Product Evaluations: Impact of a Personal Contact with a Country. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 22(2), pp.214–221. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/384b/dc1f75ccb85ce665c0ac2d72eba175ca5368.pdf

Van Weelden, E., Mugge, R. and Bakker, C., 2016. Paving the way towards circular consumption: exploring consumer acceptance of refurbished mobile phones in the Dutch market. Journal of Cleaner Production, 113, pp.743-754.

Verlegh, P.W. and Steenkamp, J.B.E., 1999. A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), pp.521-546. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167487099000239

Vojvodić, K. D., Šošić, M. D. M., and Žugić, J. D., 2018. Rethinking impulse buying behaviour: Evidence from generation Y consumers. EMC REVIEW-ČASOPIS ZA EKONOMIJU, 15(1).

Wang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, S. and Zhao, X., 2018. Effects of customer and cost drivers on green supply chain management practices and environmental performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189, pp.673-682.

Wasswa, H., 2017. SELLING NATIONALISM: INFLUENCE OF PATRIOTIC ADVERTISING ON CONSUMER ETHNOCENTRISM IN KENYA. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 0. Retrieved from https://www.oapub.org/soc/index.php/EJSSS/article/view/182/536

Watson, J., J., and Wright, K., 2000, "Consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes toward domestic and foreign products", European Journal of Marketing, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 1149-1166. https://search-proquest-com.salford.idm.oclc.org/docview/237022636?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Watson, J.J. and Wright, K., 2000. Consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes toward domestic and foreign products. European Journal of Marketing.

Wolske, K.S. and Stern, P.C., 2018. Contributions of psychology to limiting climate change: opportunities through consumer behaviour. In Psychology and Climate Change (pp. 127-160). Academic Press.

Xu, A., 2010. The cognitive processes underlying country of origin- effects and their impacts upon consumer's evaluation of the automobile. http://lnu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:371505/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Xu, B. and Chen, J., 2017. Consumer Purchase Decision-Making Process Based on the Traditional Clothing Shopping Form. J Fashion Technol Textile Eng 5: 3. of, 12, p.2.

Yang, C., Wang, H., and Zhong, K., 2015. CONSUMERS' PROCESSING MINDSET AS A MODERATOR OF THE EFFECT OF COUNTRY-OF-ORIGIN PRODUCT STEREOTYPE. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(8), pp.1371–1384.

Yeh, C. H., Wang, Y. S., and Yieh, K., 2016. Predicting smartphone brand loyalty: Consumer value and consumer-brand identification perspectives. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 245-257.

Zalega, T., 2017. Consumer ethnocentrism and consumer behaviours of Polish seniors. Handel Wewnętrzny, 369(4/2), pp.304-316.

Zeren, D., Kara, A. and Arango Gil, A., 2020. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Willingness to Buy Foreign Products in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Turkey and Colombia. Latin American Business Review, pp.1-28.

Zhang, Y., 1997. The country-of-origin effect is the moderating function of individual differences in information processing. International Marketing Review, 14(4), 266-287. doi http://dx.doi.org.salford.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/02651339710173453.

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?