How to Build a Skills Development Plan | A Personal Report

December 18, 2020

Design Build Finance Operate (DBFO): Procurement Method Technique

December 18, 2020The start of building adaptation and conservation teaches us how to take care of old buildings and make them useful today. It helps us find a balance between preserving history and being eco-friendly. This section explores the study's introduction.

Introduction

Historic buildings within the United Kingdom not only add to the character and material attractiveness of the country but also substantially contribute to the economy. Therefore the value of these buildings, which are found throughout the Kingdom, should be carefully evaluated and analysed (English Heritage, 2010a).

Find out How Heritage Promotes Growth of Tourism Industry

According to Visit London, 2011, tourism based on heritage has been one of the pivotal factors that have contributed to the growth of the tourism industry and was estimated to be about four billion pounds. Iconic buildings such as The houses of the parliament significantly contribute to the heritage value of London. However, the entire country is a diverse mix of buildings pre-dating the 20th century along with newly built heritage structures, conservation areas and various other buildings that have not been designated yet both post and pre-20th century.

The Planning Act 1990 distinguishes various historic buildings, primarily through a distinction between Grade I, II or II* listed buildings. English Heritage, 2011 points out that these grades, along with Section 69 of the 1990 Act, which designates conservation areas, will constitute a heritage building if that building has a material consideration in terms of architectural or historical importance.

Evaluate the Classification of Buildings Based on Their Significance

English Heritage, 2011c, draws the distinctive mechanism used for listing heritage buildings, such that Grade I buildings, classifying for about two point five percent in London, are those that have international importance as well exceptional interest quotient. Grade II buildings, on the other hand, constitute about five percent and are classified as having more than special interest. It is pointed out by HM Govt, 2010 that the regulation constraints listed in part L are not applicable to listed buildings even though these constraints have now been substantially relaxed. It is further stated by DCLG, 2010 that these constraints are also applicable to conservation areas; however, evaluative procedures are required for the assessment of alterations with regard to insulation, exterior cladding and double glazing.

Even though the authorities recognise the value of the built heritage, however, there are not enough mechanisms in place for the protection of this built heritage, an example of which is the cross rail bill which allows the authorities to disregard the protected status of a building if it hinders the development of a project. It is stated by the House of Lords, 2010 that despite the fact that English heritage needs to be a factor when considering any decisions regarding the same, the otherwise pattern of the authorities in disregarding this status has become pretty obvious in the previous years. The authorities need to undergo a holistic process in order to recognise and identify the importance attached to built heritage and therefore evaluate with careful consideration as to whether the refurbishment of the building will affect the unique nature of the building.

It is the responsibility of the Secretary of State for sports media and culture to designate listed buildings. Under Section 66 of the 1990 Act, it is important for the city council to evaluate the alteration plans for any listed buildings carefully. The council is obliged, per law, to carefully look into all factors that may affect the building while aiming to preserve the architecture, history and the unique component (DCLG, 2006). The government, prima facie, leans towards the preservation of such buildings but requires the council to understand the circumstances of the individual building considering facts and figures.

Moreover, as illustrated by Hansard, 2011, that any alteration work, including extensions or demolitions, affects the basic character and the structure of the building and is subject to prior approval. However, certain types of modifications to the interior or routine maintenance may not come under the scope of these restrictions; however, it is upon the authorities to decide this on a case-to-case basis keeping in mind the unique character of the building. It is further pointed out in the DCLG, 2006 that even where a building is listed, these descriptions of the building in question are not a complete picture of all the inherent value that the building has and, therefore, should not be the sole basis for consideration when deciding for alterations. (English Heritage, 2011b).

The concept of adaptive re-use of historic buildings is the primary focus of this research.

Focus of Research

This included identification of a suitable building and gaining approval for it to provide the basis, and presenting a conservation plan for the chosen building. Finally, a proposal for the adaptive re-use of the selected building while taking into account a range of issues has been presented in this research. It is noteworthy that a vast majority of the protected buildings are schools, hospitals and churches located within a residential area, thereby, refurbishing or altering these buildings, in most probability, will cause disruption in the locality for both commercial and residential occupiers. Therefore, during this study, it has been challenging to select the most appropriate building that could be best utilised for the community, given the limited time and resources. However, the effort has been made to review various local buildings and literature critically, and possible conservation plans and proposals were formulated.

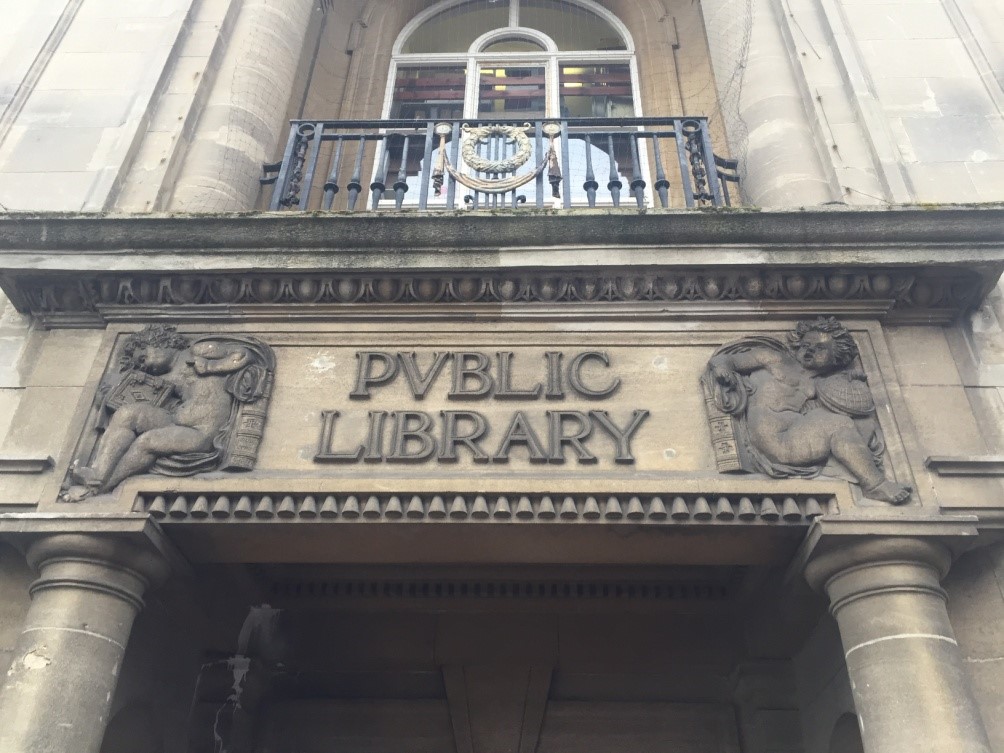

After an extensive review of various buildings, The Public Hove library was selected for the outlined purpose of the study. The Public Hove library located in Brighton was erected after a donation of ten thousand pounds by William Willet on the prerequisite of adopting the Free Public Libraries Act of 1850. The Royal Institute of British Architects got together to conduct a competition to choose a design for the library's location on Church road. The Mayor put down the first brick on the tenth of June 1907, after the design submitted by Jones and Robinson was approved in October 1906.

The library's construction cost approximately thirteen thousand and five hundred pounds, and it opened its doors to the public in July 1908. Built using the doulting stone, it comprises two storeys and is inspired by a mix of the Baroque and Revival Renaissance styles. The library had been listed as a Grade II building, which is primarily a building which is particularly important with exceeding special interest.

Proposal Statement

Before a discussion about the Public Hove library, it is important to draw reference to the three pictures attached below that will help the reader in understanding the context and the external outlook of the library as it stands today.

Figure 2 The Hove Library- Front. Figure 3 The embellishment on the exterior.

Figure 4 The side of the library building, in a semi circle.

The Public Hove library has become a place of special interest over the years and has been subject to various demolition plans by the authorities which were invariably stopped through public pressure. Once again, the public library at Hove is under threat, as per the report published by Morgan, 2015, whereby the government for council services were removed which resulted in a one third cut in the total budget. The authorities therefore, want to shift the Hove library into the Hove museum since it has become extremely expensive to run a place on its own given the maintenance and staff. Other libraries in the near vicinities such as the mobile library were shut down and the rest have had their operational house substantially reduced, thereby it is inevitable that the Hove public library will be merged into the museum (Cather, 2001).

Following this therefore the document aims at outlining the history and the development of the public library at Hove while identifying various heritage components within the library. The current proposal with the authorities aims at selling the library building and shifting it within the Town Hall museum. The basic objective of this conservation plan is to conserve the Public library in its current form by amalgamating the Hove museum located at the Town Hall within the library building.

Scope of the Plan

The scope of this conservation plan for the Public Hove library, as highlighted in the section above is to document and justify the significance of the library which will include the building in its current form, any archaeology, paintings, walls and architecture. It does not however go into in-depth detail of the socio economic interaction and significance of the public library in Hove, but aims at identifying the tangible components of heritage that can be conserved and sustained with a refurbishment of the surroundings to include the Hove museum into the library building.

Background of Public Hove Library

Before continuing with the discussion on the proposal statement of the adaptive re-use of the library, it is important to thoroughly investigate, analyse and review the historical importance of this building.

Establishment and Development

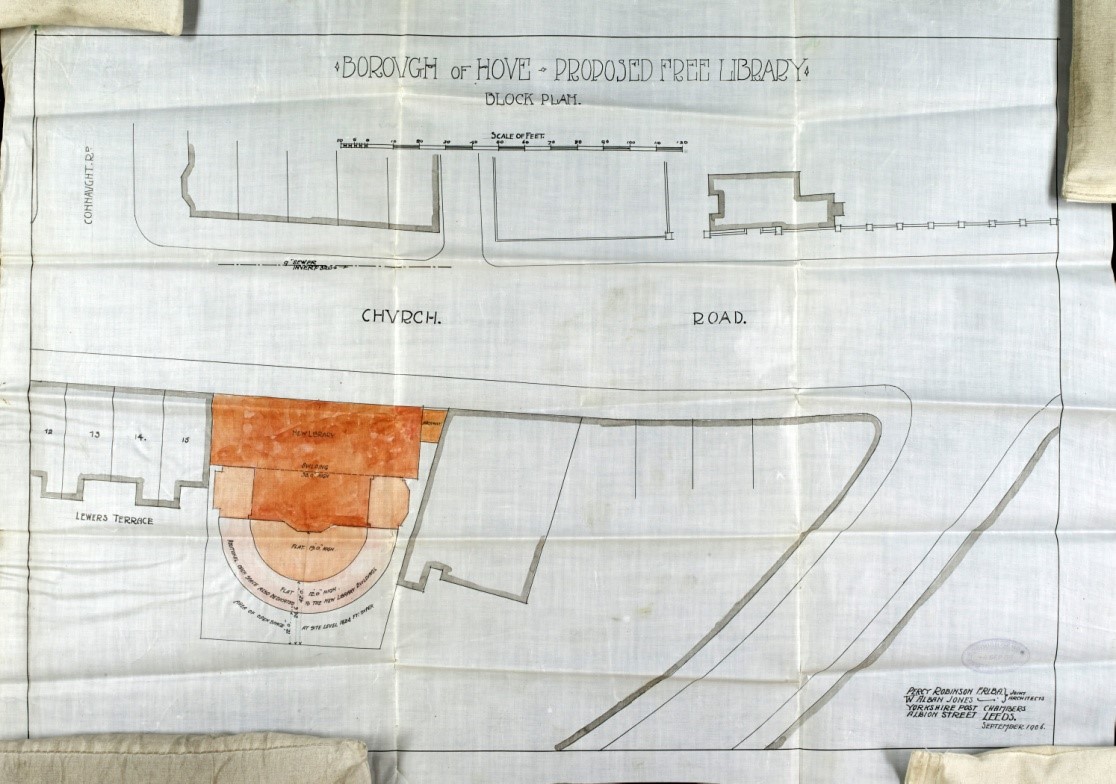

The establishment of the Hove Public Library began with the formation of a committee in 1890 which constituted of Hollamby, Henriques Isger and Knipe with the purpose of laying down steps for the establishment of a free public library within the Hove area, as shown in the figure below;

Figure 5 Maps of the Hove Area

However, by the end of the year, the report presented to the Hove Commissioners stated that it would be expensive actually to build a library. However, they could alternatively rent a place to use as a library for hundred pounds a year. The Public Libraries Amendment Act 1890 required the commissioners to obtain consent from the voters before undertaking such a step. This requirement was used as a loophole, and the Commissioners stated that establishing a public library within the Hove district was beyond the powers conferred upon the Commissioners. This did not sit well with a few influential residents who subsequently signed and sent a petition to the Hove Commissioners requesting them to issue slips with options to vote for or against the establishment of the library. The total vote was collected on the 31st of March 1891, which showed that one thousand one hundred and ninety-seven residents wanted to establish a free library. In contrast, only five hundred and two voted against it, and four hundred and ninety-nine residents did not send in a reply.

Willet, William offered to rent out rooms on Grand Avenue for the Hove Commissioners, which included the ground, the first and the second floors, including a basement, illustrated through the layout and elevation details as below;

Figure 6 Layout plan of the building

Figure 7 Library Building Elevation Diagram.

Negotiations proceeded for the amount of money for rental purposes; however, Willet stuck at hundred pounds per annum for the first two years, increasing to one hundred and fifty pounds pursuant to a seven-year lease. These rental deposits did not include any maintenance or repair charges incurred in the library's establishment.

The four houses used as the library were built in red stone using the Surrey vernacular style by Faulkner, distinguishing them from the other houses on Grand Avenue, which were built in yellow stones. These houses, later in the year 1992, were put up as listed buildings. By the end of 1891, five hundred pounds had been set aside by the Hove Commissioners to use for the library. However, this amount needed to last at least six months. This would not have been possible if all the rooms were fitted beforehand because there would be no money left to buy the books and other stock. The Hove commissioners subsequently drew their focus on refurbishing a reading room for the initial six months. They founded a reference library room, hoping to get sizable donations from the people. Amongst the few prominent donations were thirty-six volumes of Britannica by Knipe, one hundred and fifty volumes in Braille for the blind people by Ms Connolly, and one hundred and three volumes of parliamentary debates recorded within the Hansard by Sir Julian Goldsmid.

By the end of December 1891, a news room was opened within the library premises, with its operational hours starting from 9 am till 10 pm. The residents had access to ten daily reporting papers and thirty-two weekly and thirty monthly news reports. Initially, it was thought by the commissioners that there was no need to hire a librarian since the caretaker, James Darton, could manage to take care of all the daily doings. The first significant notices placed within the library were in 1892, which required the readers to spend no more than fifteen minutes on one particular paper if it was needed for another and further needed then to keep one piece of paper with them at a time.

John William Lister was appointed as the first Chief librarian at the age of twenty-two. Within a month of his employment in 1892, he presented a recommendation list of forty books that should be present within the library's lending section. The lending section opened its doors to the public at the end of 1892. It noted a diverse readership including one hundred and ninety-nine students, two hundred and nineteen gentlemen, and one hundred and thirty-nine domestic help servants, among others. The lending library was decorated with ornaments and collection tables provided by various residents, including a reproduction of Michelangelo and Raphael’s cartoons, weapons, a sword and a knife. With the dawn of 1894, the residents were given the reference library, with its operational timings from ten am to nine pm, except for Friday afternoons when the library closed at two pm in the afternoon.

With time, the premises at Grand Avenue became the wrong location for the operation of a full public library since it was too small a place to accommodate so many people. An example is that the books were issued using a ledger system that managed to give and discharge one hundred and fifty books in an hour, resulting in large queues and people waiting at the small entrance to issue the books. The library was particularly overcrowded on Saturdays, and even though the lease was extended in 1898 for another three years, and towards the end of these three years, the floors had begun to give out under the humungous weight of the books, the furniture and the people.

History of the Hove Public Library

The library Commissioners thereby decided it was time for the library to have its own distinct premises. They came across a building on Third Avenue and subsequently leased it, moving the Public Hove Library to Third Avenue in June 1903.

Andrew Carnegie, born in Scotland in 1835, amassed a vast amount of wealth and began providing sizeable donations to public libraries around the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States (Waite, 2011). The library Commissioners had sent a private appeal to Andrew Carnegie for a donation. After the latter had died, Isger, the mayor of Hove, received a letter from his secretary stating that he had donated ten thousand pounds to erect a building to constitute the free public library provided that the Free Public Libraries Act was wholly implemented. The council was not happy with the council for sending the appeal for a donation. However, Henriques completely supported the donation money and went on to state that he would donate three thousand volumes of his beautiful illustrations only if the library had proper premises and building.

The library councilman suggested the site on the church road, which was the initial position of the library, but because of the presence of the depot, it was not possible then. However, the library council were not keen on getting the depot land since they wanted the library and the technical institute of Hove to be situated right next to each other since they believed that the latter would receive a substantial amount of funding from the Essex county council. It took years for the offer of Andrew Carnegie to be taken up. Finally, in March 1905, the council appropriated permission from the government and relevant local authorities to acquire the depot land and subsequently begin the construction of the Hove Public Library (Middleton, 2015).

The council and commission had set the date of Eighth July on 1908 as the grand opening date for the Hove Public Library; however, the day turned around to be dull and rainy, and the authorities had to put up barriers to keep the residents away from the building. The Countess of Jersey was invited as the Chief Guest, and after formally opening the public library at Hove, she gave a long formal address to those present. Moreover, the mayor of Hove and mayors from Brighton, Worthing and Lewes were also present within the formal opening committee. The mace bearer took the front lead with the mayor dignitaries present in between and followed by the town clerk dressed in a gown and wig at the end.

Since this was a big event, it had to be recorded in the history of Hove; therefore, the names of the mayors, the committee members and the name of the builder were engraved on a brass plate and put up in a central position in the hall. However, these were later removed to put up other advertisement notices. In a usual round of library cuts, the committee began cleaning out the basement and the music library and found the brass embellished names in the storage (Middleton, 2015). The brass plate had vanished out of the storage after a few years, and the only reminder left of it was the thick oak plaque on which the coat of arms had been put up for the brass plate. This thick oak plaque was presented to the Museum at Hove, and they displayed it in their inventory with a false attribution to the Town Hall at Hove. On the other hand, the foundation stones remained concrete within the hall, which could be attributed to the fact that it is attached to the structure and hence a part of it; therefore, it will be difficult to remove the foundations.

There were various bequests to the Hove Public Library, namely Henriques, who had promised to donate his library donated twenty-seven hundred volumes to the public library; however, until about 1914, there was no official figure in the accounts for these volumes. Ms Donne presented very rare and important books to the library in the 1920s. Amongst other bequests, there was a watercolour drawing portfolio of the Hove buildings and churches, eighty volumes of publications associated with Charles Dickens, and one sixty-three volume of books by Gallard in 1916 (Middleton, 2015).

When the library opened in the year 1908, the library's opening hours had been altered so that the staff did not get overworked. Instead of closing at nine pm, the library closed at 8.30 pm, and the reading and reference rooms were kept open for eleven hours.

Tangible Heritage and Conservation Proposal

The inherent significance of the Hove Public Library lies in the fact that it was designated to be Grade II listed building under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. A building is listed as a Grade II building with historical and architectural significance attached to it, as illustrated by an extensive historical study of the building. The Hove Public Library, even though it lacks the basic appeal for tourists, has significantly contributed to the character of the Hove area. Therefore, it is essential to understand the significance of the library building. The current character of the building provides a pleasant setting for students or readers who reside within the area, and it serves to be a pleasant surprise to many tourists that may accidentally stumble by it. After the library was moved to the third avenue and built from scratch using unique materials such as the Doutling stone and red bricked walls, it stood out from the rest of the crowd. It complemented the juxtaposing structures and stonework, including embellishments (Middleton, 2015). The Hove public library is visible from various public viewpoints, including the area around it, since the land is flat without any physical boundaries such as hedge fences in place, as shown in the figure below;

Figure 8 Library Building View

The Architectural Analyses of the Building

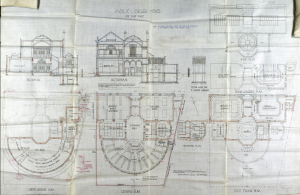

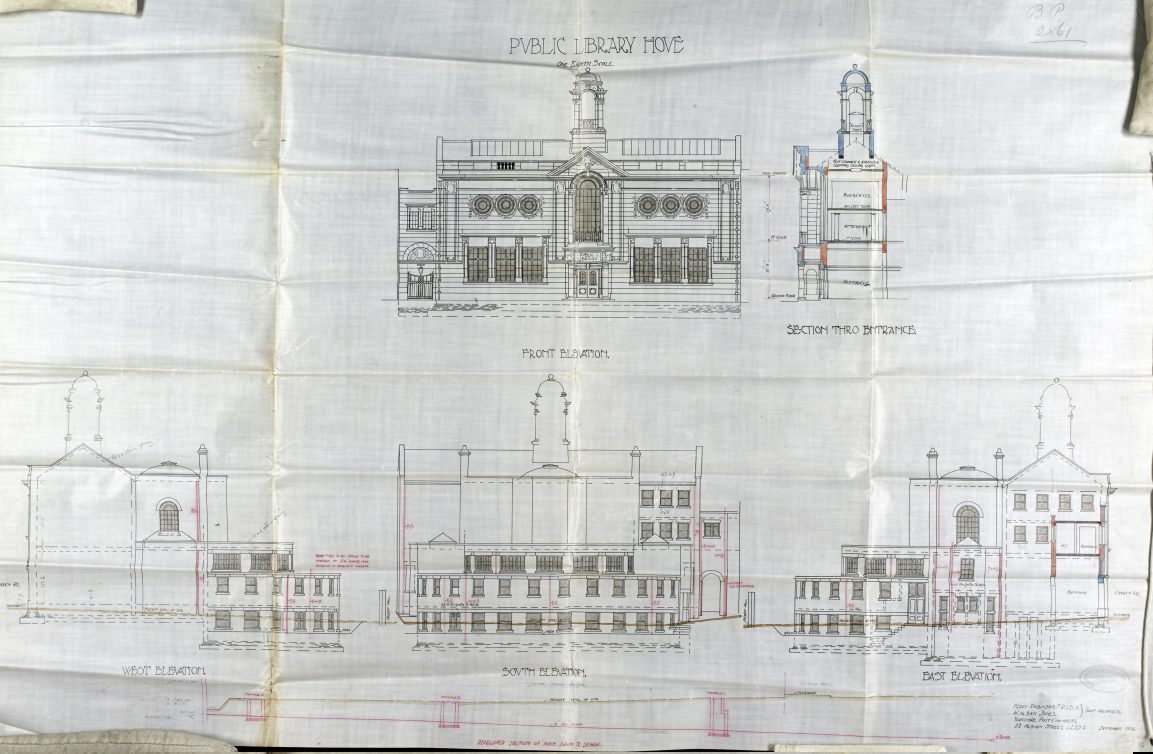

Before recommending the re-use or conservation plan of this historic structure, it is necessary to critically assess the architectural heritage and analyse the current status and usefulness of the building in use, as deciding on any modifications can prove to be highly significant in terms of the sustainable and productive use of the structure under investigation. After receiving the approval to begin construction, the Royal Institute of British Architects started a competition to allow architects to submit their designs for the library. In October 1906, Robinson and Jones's plans were selected, and the construction work began in 1907 (Middleton, 2015).

The front of the building, attached above, was designed taking inspiration from the renaissance style and used the Doulting stone for construction—the top of the building is comprised of balustrades and a classical central dome. The dome survived many years. However, it was removed in 1967 by Hall and Company because its condition was continuously deteriorating. The front of the building was decorated with ribbons, scrolls, flowers and amorinis on each side of the sign, ‘’pvblic library’’.

Figure 8 The V in Public Library. Roman numerology is used in all Carnegie buildings.

It is also important to note that the v in public was not a mistake, but all buildings that Andrew Carnegie made possessed roman numerals which did not have a ‘’u’’ in them. Incidentally, this stone had been covered with a plastic sign for years, and until very recently, it was not visible. These little architectural details provide the essence of the building; therefore, selling the building for residential or commercial purposes would diminish its inherent value of the building.

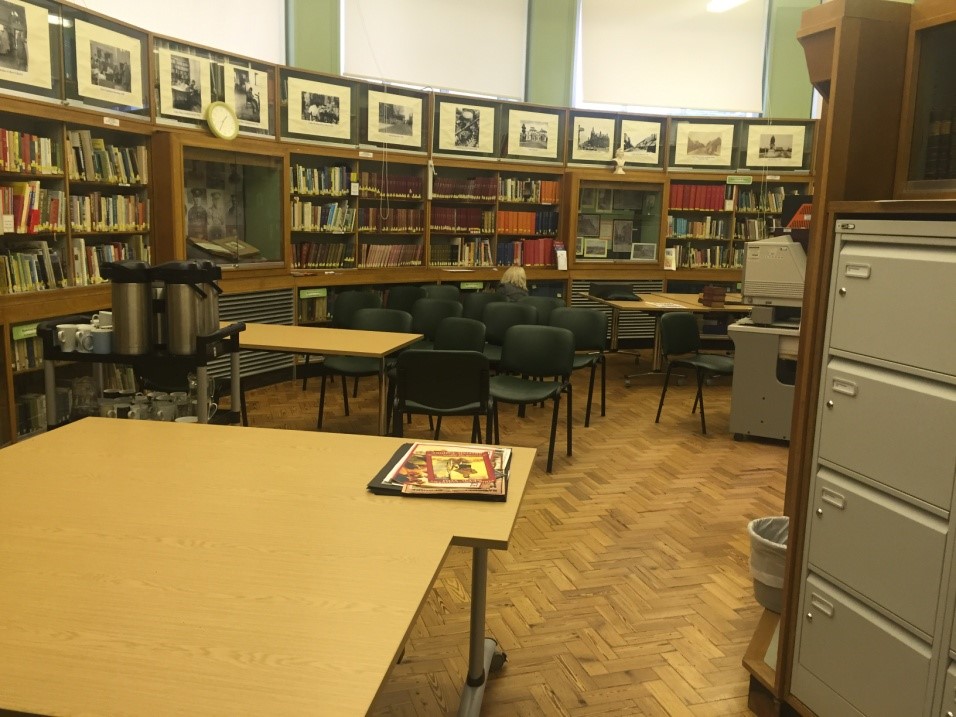

The red brick building spanned out from a semi-circle towards the southern part, and the interior is designed to allow natural light to flow, ensuring the place to airy, light and spacious while giving out a great look of the Edwardian era, illustrated through the picture attached below.

Figure 9 The rooms built on the Edwardian Theme, light and airy.

The huge windows on the ground floor had embellished texts which included: knowledge is power by Francis Bacon and economy is half the battle of life by Charles Spurgeon.

A central glass dome was placed in the top storey to allow light to penetrate and diverge into all library areas.

The staircase has been embellished and light up by a huge stained glass window that depicts the coat of arms at the Hove, illustrated in the picture on the left.

Also, another stained glass lighting the stairway is the knowledge of lamp in the Aladdin genie lamp genre theme. Ornate mouldings of plaster were found on cornices and ceilings, while the arches and columns were constructed using Trieste marble; however, as long as anyone has seen these columns, arches and ceilings, they have all been covered with paint.

Figure 11 The coat of Arms on a stained glass window in the library. |

Australian oak had been used in the construction of bookcases within the reference library that was situated on the first floor. Initially, the bookcases had glass openings on the front, whereas the side panels of the bookcases had flowers, fruits and leaf garland embellishments and carvings. However, during a process of rearrangement in the 1980s, these embellishments and carvings were wiped off. The flooring was made of thick blocks of oak and was of such high quality that even today, after one hundred and seven years of being fixed, they have not deteriorated. The doors to the entrance are made from solid oak and have bevelled glass panes, and brass door handles. The staircase was installed in the year 1911, and it also had brass railings. For many years, pink paint covered these brass railings; however, now they are kept in good condition and continuously polished (Cunningham and Anderson, 1998). The year 1920 saw the passing of a proposal for locating the children’s library in the basement. Therefore by July 1920, the basement with a side entrance had been opened up for the children, which has now been shifted to the ground floor of the building in front of the entrance.

The Proposed Re-Use Models of the Building

In September 2003, a suggestion was put forth by the council members of Hove and Brighton to move the Hove public library into the basement of the town hall, thereby vacating the current premises (Lowe, 2007). It was argued that the building was old and could not meet the modern requirements and regulations laid down by the government, one of which was to provide a lift for the elderly, which was deemed impossible at that time because the building would have been unable to sustain extra weight. This was probably a false herring since today there is a perfectly functional lift at the premises. A massive protest, including the ex-council men of the library, took place outside the premises, and the Hove library was saved (Morgan, 2015).

However, as discussed previously, 2015 marks a difficult year for Hove library since the authorities are again pursuing the idea of closing down the library and amalgamating it with the museum. The authorities believe that the building is expensive to run. Since the Jubilee library under the Brighton council is suffering a huge debt, most proceeds from selling the library building will pay off that debt. The council members have already begun to talk about an auction to raise one million pounds from selling this building without any mandatory public consultation under the statutes.

From the research completed on this case study, and considering the current difficulty of operating the library, the following re-use plan is proposed;

“Development of an in-house museum in the facility, while utilising the current structure with parts of the library use intact”.

As presented in the previous chapter, this infrastructure has a long history which must be preserved. The current conditions of the building also suggest the structure is more or less in good shape, and the structural specification can be used to re-model the building utilisation aspects. The development of the museum within this facility without having to demolish the structure or undertake huge medication can be considered a viable option under the current circumstances.

The aforementioned discussion points out one very important factor that needs consideration for this re-use proposal. The condition of the building, primarily the interior built 107 years ago, still stands tall, including the flooring, the basic wood panels and the structure itself. Therefore, maintenance of the structure, including repairs, should not be considered an added burden. However, conservation of the current structure in its particular form should be regarded so that strength optimisation techniques can be applied and proper concealing through stone coping where needed (Priemus and Flyvbjerg, 2008).

The brickwork on the exterior of the building is an inherent component of the library which has been set in bright red stone, the doulting stone. However, it is also noteworthy that the sharp edges of the bricks have now darkened given the amount of rain, thereby softening the elevation of the brickwork. The quality of craftsmanship, if kept in check, can be used for repairing or replacing bricks on a necessary base, after which the edges can be cleaned to give away any dark stains.

Most of the interior fixtures and features have a great history and significance for the library and the community it operates. Even though most of the fittings have a natural life span, it is pertinent to point out here that the condition of the Hove public library remains good with little repairs and maintenance. Some materials, such as bookcase panels, will have a considerable life span given minor maintenance work (Martin, 2010).

Thick oak has been used for flooring, which was a part of the original design but proved to be a significant factor in giving character to the inside of the building. The flooring is in good condition even after one hundred and seven years of use. The flooring can be easily cleaned using a wax finish with a dry mop. Therefore the maintenance of the floors does not pose to be a problem.

The glass dome at the library's centre provides an airy feel to the building and diverges light into all corners of the library. The dome was restored very recently before the scaffolding was found underneath it. The dome's appearance can be easily maintained with cleaning supplies and does not require any alterations. Similarly, the glass stained windows have various beautiful inscriptions and designs such as a coat of arms or the embellished motto, ‘’May Hove Flourish’’ do not require regular maintenance; all that is needed is proper cleaning for them to allow the light in and shine providing the air of elegance in the library structure.

Some further various external structures and rooms are worthy of conservation and being a part of the proposed museum at Hove. First and foremost, the roman numerical signifying the use of V instead of U in public bears a great history in itself since the founder of building Carnegie used this in all his buildings (Ramsden, 2001). Thus it suggested keeping the norm and add-in an additional name for the museum underneath this name. Moreover, since the proposed plan is to keep parts of the library intact, it would be advisable to keep the name at the entrance of the building.

It is important to note that expanding the public library from renting rooms to its own personal building is a huge achievement. An important component of the interior rooms is the Woslesley room, which was made as a tribute to the Wolseley family but is being used to display documents and can be re-used to place high-profile unique arts. The room has been a home to various art exhibitions which provide the library with a touch of history and glamour from the past. Other rooms such as the reading room, the reference room and the music library all pose as significant heritage assets for the building, which can prove to be highly influential for the proposed museum, and removing them and putting them in a space shared within the town hall will be not only derogatory but also useless (Tygonak, 2008).

Therefore, this scenario to operate the museum based within the town hall, in conjunction with the part of the library, can be considered to be highly productive, as this plan does not involve moving the building but creating a trail of historic displays within the library to pose as museum assets. This will not only reduce the cost of the maintenance but furthermore allow the funds that are allocated to the museum to be used within the library for its upkeep. If nothing, this aforementioned section reinstates an important point, that is, the maintenance of the building is not a concern since it stands tall and sturdy even today. Basic cleaning supplies and repairs, when necessary, are optimum for operation.

Each can be altered in its tangible settings without demolishing or removing any rooms to allow for the space to be utilised and an already operational library room. An example is a Woslesly room itself. It provides a home to historical documents, deeds, and art exhibits and, therefore, can be adjusted to include some memorabilia from the Hove Museum. Similarly, the reading and the reference rooms can have a trail of historic memoirs through an illustration of their historical importance, which will captivate the readers and gain their interest. The section below illustrates this further through an analysis of the intangible historical heritage that can be conserved using tangible components from the Hove Museum.

Historical Heritage and Conservation Proposal Plan

As discussed previously, the history embodied within the Hove Public library is of utmost importance and must be preserved. First and foremost, the library's development and construction through various phases and obstacles are highly significant. Any building that boosts such illustrious history must not be the subject of sale.

An important event noteworthy in continuation of the previous section is the inscribed names of all the men and women that took part in the World War I. Mr. Lister, the librarian meticulously collected detailed inscriptions of the work done by men on the war field (Middleton, 2015). He maintained six large box files with pictures, heroic accounts, postcards, newspaper cuttings, and other memoirs. This being an essential historical event has been preserved in a tangible form that can be displayed using monuments displayed within the Museum depicting the work in the field war. The authorities can collect memoirs, sculptures, weapons and other items of interest placed in the Town Hall museum and have them displayed with a scripted history.

It is important to note that the public library also served as a Hove museum from 1914 to 1927 until the authorities purchased Brooker Hall to shift the museum. However, by the end of 1927, all the items had been moved to Brooker hall, and the Hove now boosted a separate Hove museum for the residents and travellers (Middleton, 2015). This is inherent to the discussion of the conservation plan since if it had been put in place almost a century ago, it could be a viable option today. Running costs of the museum at the Town Hall in comparison to amalgamating it with the library will show a definite learning curve towards the latter. Moreover, shifting such a vast library into the basement of the Town Hall would not only take the essence of the library away but also give rise to the initial problem of space and location that the authorities faced when the library was on Grand Avenue (Morgan, 2015). Space was the primary concern when the authorities decided to shift the building, and reverting to the same circumstance in today’s day and time seems unreasonable and hasty.

The Wolseley room, well known for its historical component, has, over the years, become an art exhibit of various paintings, with period exhibitions being held to promote local artists (Morgan, 2015). Moreover, the room also exhibits and stores all the old documents and deeds for the old Sussex, and by the end of 1947, the room had stored and displayed over three thousand deed documents, illustrated through the pictures below.

Figure 12 The Woslesly Room displays history through pictures. [Left]

Figure 13 Illustration of an aerial view of the building from the top. [Right].

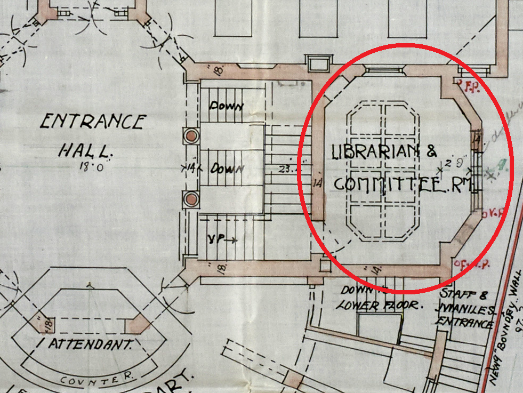

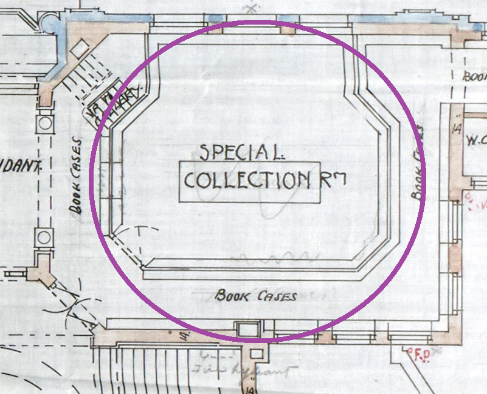

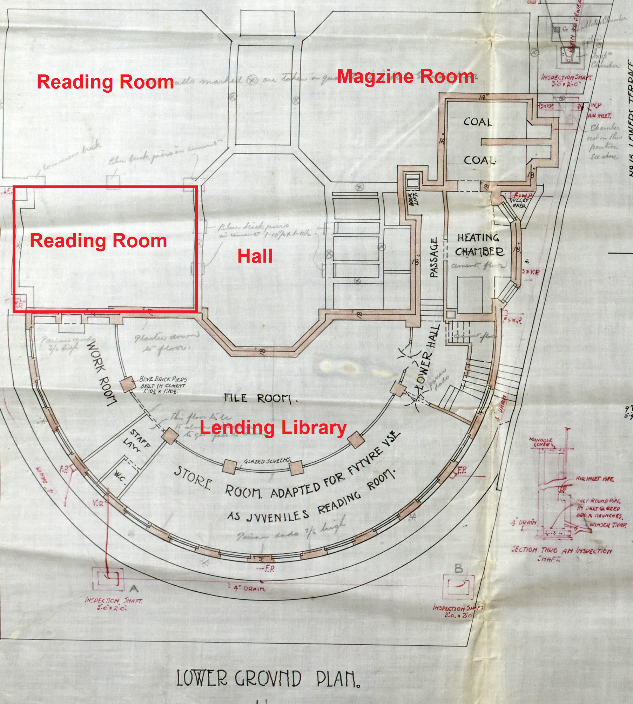

The library in itself provides a memoir to the history of the Hove area through souvenirs, pictures and art. Drawing reference to the Figures 14 to 16 below, the highlighted red area shows the position of the Woslesly room and the juvenile reading room; the purple area illustrates the special collections area, and the blue area illustrates the file room.

Figure 14 The plan of the building. The highlighted red portion is the Woslesley Room [Left]

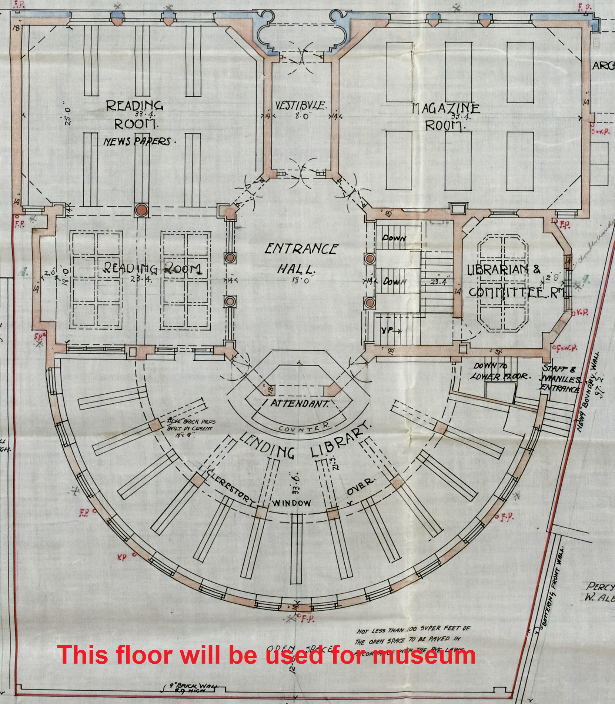

Figure 15. First Floor plans of the building, the height purple is the Special Collection Room. [Right]

These particular areas have been highlighted to illustrate the space utilisation within the library. Such that the Woslesley room, shown in Figure 14, is already an exhibit of arts and history; therefore moving monuments and souvenirs from the museum to this room and corresponding them with the documents and deeds present in the room may be time-consuming; however, it will not only save operational costs on the whole but lead to better organisation of both the documents and the structures. Similarly, the unique collection room in Figure 15 can again have a trail of monuments from the museum.

The juvenile room has now been shifted to the ground floor entrance, which is also the entrance for the Woslesley room. Therefore the space initially provided to the young section can be very quickly utilised for the display of museum items. The room next to it, referred to as the file room, can be utilised further for the same purposes. Using these two adjoining rooms is viable because the semi-circle structure provides more surface area for display and movement; secondly, it brings history and its tangible components into one space together.

The Hove library furthermore has a music room, which after an initial opening in the Covent Garden, was shifted to the first floor of the library building in 1983 (Cunningham and Anderson, 1989). This room is opposite the special collections and, therefore, provides a good space and theme for museum items related to music genres or special domestic instruments to be displayed. For example, domestic folklore instruments found in the museum can be placed near the music collections on domestic folklore along with the books giving information and references for the same. This will ensure organisation and optimum utilisation of not only space but also the reader’s time (Tyack, 2008).

The authorities can perhaps divide the area into themes according to interests and display the relevant books and museum items with their descriptions through references to the books around them. Another option could be replicating the ground flood floor plan on the lower floor. This will require developing of the lending library, reading rooms and magazine room in the lower ground floor through installation of partitions. The books as well as furnishing items will be shifted the lower ground floor form the ground floor, and shall be placed at the identical locations. This has been illustrated as below;

Figure 16 The lower ground floor proposed alternate plans. The red highlighted portion shows the changes to be made initial plan. The floor plan of the ground floor is replicated (left). The complete first will then be used for the museum

In this proposed plan, the first floor plan will be used to place the both museum items and the library books, to allow the community explore both at the same time. This would also interest the young communality to visualize the historical aspects of many generations and read the related literature so they are able to understand the presented concepts. This plan can also be considered to be a viable options to generate revenue for the operations of this important heritage, however initial support from the Government will be required facilitate these developments,

Heritage Conservation Policy- Application and Implications

The previous sections aim at establishing the importance of the Hove public library as an asset to the heritage while identifying the various vulnerabilities that are prone to harm and deterioration. This section therefore aims to outlining various conservation policies that can be applied to not only reduce the probability of any harm accruing to the building but also preserve it in a form that proves the significance of the building and the library itself.

The purpose of the conservation plan is to highlight and implement the relevant policy regulations so that it can become a useful resource for management and future viewing. The National Planning Policy Framework 2012 lays down provisions which have to be considered when aiming to alter any listed building. The Hove public library in its current form as a library space and a social place proves to be its optimum use and permits should be gathered in line with Para 131, 132, 133 and 134 of the National Planning Policy Framework [‘’NPPF’’] 2012. Alterations in a limited form are inevitable in order ensure that the building remains in its form while complying with the modern building authority regulations. A possible idea is to not move the building but actually convert the library into a museum plus library with artefacts and displays. Applying the NPPF, any alterations that are conducted must be done with keeping in mind the significance of the library as an asset of the heritage and therefore as per Para 134, the alteration that give less than substantial harm to the building must be able to provide substantial benefit to the public (Martin, 2010). Moreover, Para 132 specifies that any alteration which aims to providing substantial harm to the building must be an exception. Para 137 makes it a requirement for the alterations to be a positive contribution while revealing the asset significance of the library.

Before any alteration work is done, given that the Hove public library is a Grade II listed building, therefore even minor repairs require pre requisite consent. Domestic estate services need to be consulted in order to define the parameters of construction and demolition (Cassar, 2009). With the current plan in place of selling the public library it seems that changing the entire significance of the building from a library and a social space to a commercial/residential property for the purposes of sale not only diminishes the significance of the building but also contravene with the policy regulations (Martin, 2010).

It is apparent from the aforementioned discussion the Hove public library is a significant component of not only the community at Hove itself but holds a great deal of architectural and historical interest. For the purposes of this conservation plan, the significance of the building has been identified and various components, though these are not exhaustive have been highlighted for the purposes of conservation. Given its status as a Grade II listed building, in line with the various historic events that have transformed the building, it seems to be unjust and unreasonable to sell such an important asset of the community (Ramsden, 2001). The previous section identifies the vulnerabilities of the building and highlights its use as a public space which can be amalgamated with the use of the Hove public museum inside the library rather than aiming to move the library into the town hall as the authorities are contemplating at the moment.

It is stated in the GLA, 2011, that carbon emissions and sustainability are two inherent factors that must be taken into consideration when aiming to refurbish any building that has a heritage value, through an application of probable mitigation measures considering climate change and any potential harm. In most circumstances, the built heritage is evaluated beforehand keeping in mind various factors such as technology, the hassle, complexity of the structure and various skills and scales. It was estimated by Wilson and Piper, 2008 that about twenty five percent of the total housing built in the year 2050 would use materials that are traditional such as no damp proof course or solid construction or even glazed bays, therefore it is important to analyse as to what extent should and can these housing projects be altered as a part of the project.

GlA, 2011 states that almost forty nine percent of the carbon emissions are accounted to the already existing buildings within the United Kingdom, therefore it is proposed that during the refurbishment work of this structure, the stakeholder must consider the effects of carbon emissions. This poses a greater challenge for the buildings located inside London since most of the built heritage predates to the Victorian era which includes an estimate of twenty thousand listed buildings, over a thousand sites of conservation and over a hundred thousand buildings that are protected. The authorities including engineers, managers, owners and occupiers are all required to take precautionary measures when altering these building so that they don’t harm the character of the building and the city, as well protect the overall environment (Cassar, 2009).

References

- Cassar, M., (2009). Sustainable Heritage: Challenges and Strategies for the Twenty-First Century. In APT Bulletin: Journal of Preservation Technology (40:1) [online]. Available at: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/18790/1/18790.pdf pp. 3-11.

- Cather, S. (2001). St Mary’s Church, Houghton-on-the-Hill, Norfolk: Additions and Comments on Draft Conservation Plan. Unpublished report for The Friends of St Mary’s (10 June). London: Conservation of Wall Painting Department, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London.

- Cunningham, C. and Anderson, J. (1998). eds., The Hidden Iceberg of Architectural History, Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain.

- DCLG, 2006. Review of Sustainability of Existing Buildings: The Energy Efficiency of Dwellings – Initial Analysis. London: DCLG.

- DCLG, 2010. Planning Policy Statement 5: Planning for the Historic Environment. London: TSO.

- English Heritage, 2010a. Heritage Counts 2010: England [online]. Available at: http://hc.englishheritage.org.uk/content/pub/HC-Eng-2010

- English Heritage, 2011b. The National Heritage List for England [online]. Available at: http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/mapsearch.aspx

- Greater London Authority, 2011a. The London Plan 2011 [online]. Available at: http://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/planning/londonplan

- Greater London Authority, 2011b. Mayor declares London is ‘retrofit ready’ and ripe for investment to make millions of buildings energy efficient [online press release] 22 June. Available at:www.london.gov.uk/media/press_releases_mayoral/ mayor-declares-london-‘retrofit-ready’-andripe-investment-make-million

- Hansard, 2011. Memorandum submitted by English Heritage (L 42). In Commons Debates: Public Bill Committee, Session 2010-11: Localism Bill. [online]. Available at: www.publications.parliament.uk /pa/cm201011/cmpublic/localism/memo/loc42.htm

- House of Lords, 2008.The Crossrail Bill [online]. Available at: www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200708/ldbills/070/08070.8-14.html#J621

- http://portsladehistory.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/hove-library.html [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=365513&mode=quick [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/heritage-at-risk/buildings/. [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- https://www.historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1298670 [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- geograph.org.uk [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/ English Heritage [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- imagesofengland.org.uk [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- Lowe, R., (2007). Technical options and strategies for decarbonizing UK housing. In Building Research & Information, 35:4. London: Routledge. pp 412-425.

- Martin, L. (2010).Scheme Design Report for the St. Cross Building, Oxford (unpublished, available from Oxford University archives)

- Middleton, J. (2015). Hove, Portsland and Brighton in the Past. Available at: http://portsladehistory.blogspot.com/2015/04/hove-library.html. [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- Morgan, W. (2015). We cannot afford to keep the Hove library in current form. Brighton and Hove Independant. Available at: http://brightonandhoveindependent.co.uk/warren-morgan-we-cannot-afford-to-keep-hove-library-in-current-form/. [Accessed 18 November 2015].

- Priemus and B. Flyvbjerg, (2008) Decision-making on mega-projects: cost-benefit analysis, planning and innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ramsden, S. (2001). Baths, Wash-houses, swimming pools and social history: a case for conservation. University of York MA Dissertation.

- Taubman, A., Webb, P., and Wetton, J., (1990) Everyone’s A Winner The History of Sport in and Around Manchester.

- Tyack, G. (2008). Oxford: An Architectural Guide. Oxford Publishing Group.

- Waite, R., (2011) Roundtable: renewal and retrofit. In Architects’ Journal [online] 25 March. Available at: www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/-roundtable-renewal-and retrofit/8613054.article [Accessed 18 November 2015].

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?