In the intricate web of public perspectives on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), the lens through which identification unfolds is nuanced by a complex interplay of factors. As we delve into the landscape of IPV, it becomes evident that the dynamics shift when the abuse is perpetrated in person compared to the distinct realm of technology, unveiling a mosaic of perspectives shaped by the convergence of personal, societal, and technological influences.

Outline

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Attitudes

- Aims and Hypotheses

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- References

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a complex and pervasive issue that affects millions of people worldwide. It encompasses physical, emotional, psychological, and even technological abuse. While society has made strides in recognizing and addressing IPV, there remain significant variations in public perspectives, especially when it comes to identifying IPV and understanding the differences between in-person and technology-based abuse.

In this blog, we will delve into the factors that influence public perspectives on IPV, as well as the distinctions in how IPV is perceived when it occurs in person compared to through technology. Factors such as cultural norms, gender stereotypes, and the lack of awareness and education can shape how individuals view IPV. Furthermore, the differences between in-person IPV, characterized by physical violence and overt abuse, and technology-based IPV, often involving cyberbullying and online harassment, present unique challenges in terms of recognition and understanding. By exploring these nuances, we aim to shed light on the complexities of IPV and the need for a comprehensive approach to addressing this pressing issue.

Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a significant societal concern, accounting for 15% of all violent victimizations in the United States between 2002 and 2012 (Truman and Morgan, 2014). It has consistently been a prevalent issue, especially victimizing women (Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, and Lozano, 2012). IPV encompasses various forms of abuse, such as physical, sexual, stalking, and psychological aggression, inflicted by a current or former intimate partner (CDC, 2015). This can manifest in behaviours like physical violence, emotional abuse, sexual coercion, surveillance, and isolation (Krug et al., 2002). Over time, the terminology and societal attitudes regarding IPV have evolved.

Historically, IPV was neither recognized as a criminal offence nor condemned, often trivialized and even treated with humour (Jacquet, 2015). Before the 1800s, it was referred to as 'wife battering,' which was perceived as a legitimate way for husbands to assert authority over their wives (Clark, 2011). However, during the late 19th century, Western societies began to shift their perspectives and introduced laws and regulations against 'wife battering.' This term was eventually replaced with 'domestic violence' and 'IPV' when focusing on violence by an intimate partner. Until the 1970s, IPV was largely regarded as a private matter, with limited attention from the Criminal Justice System (CJS) (Schechter, 1982). Since the 1970s, the CJS has made substantial strides in acknowledging IPV as a crime. Despite legislative efforts, IPV remains a significant societal issue, especially when addressing non-physical violence, which can be harder to establish due to the absence of physical evidence. This issue is particularly concerning since both men and women are more likely to experience non-physical IPV than physical IPV (ONS, 2019; Woodlock, 2014).

The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (2010) revealed that over a third of women and more than a quarter of men in the United States have been victims of rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner at some point in their lives. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (2019) reported that 4.2% of adults aged 16-74 experienced some form of violence committed by an intimate partner in the year 2018-2019, encompassing non-physical abuse, threats, force, sexual assault, and stalking. It further disclosed that 17.6% of individuals over the age of 16 had encountered intimate partner violence. Research, including Emery (2010), strongly suggests that IPV is significantly underreported, influenced by factors such as not recognizing the event as a crime, reluctance to be seen as a victim, or negative perceptions of law enforcement. Furthermore, the stigma associated with IPV often deters victims from seeking help, alongside fear of further violence and economic dependence on the perpetrator (Kennedy & Prock, 2018; Wolf et al., 2003; Vranda et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2011; Fugate et al., 2005).

While the terms IPV and domestic violence are often used interchangeably, IPV specifically pertains to violence within romantic relationships. It is a multifaceted issue encompassing both physical and non-physical forms of abuse, with both men and women experiencing non-physical abuse more frequently than physical abuse (ONS, 2019; Woodlock, 2014). IPV is a global concern that transcends gender, culture, and sexual orientation (Coker et al., 2002; Archer, 2006; Vandello & Cohen, 2004; Renzetti & Miley, 1996). Certain risk factors, such as gender and age, make individuals more vulnerable to IPV (Brenner et al., 2013).

As technology rapidly advances and becomes more accessible, it brings advantages and risks. The prevalence of internet usage has grown significantly, transforming how people communicate and connect (Statista, 2020; ONS, 2019). Technology plays a central role in the lives of adolescents and young adults, altering how they engage in romantic relationships (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Connolly and McIsaac, 2011). Online dating and social media have redefined how people meet potential partners and engage in dating (Baker and Carreño, 2016; Vogels, 2020). However, this digital shift has also introduced new avenues for IPV. Technology can be used for monitoring, tracking, excessive messaging, and the unauthorized distribution of intimate images, contributing to IPV (King-Ries, 2011).

This paper predominantly focuses on non-physical IPV, including stalking and coercive, controlling behaviours. It underscores the significance of recognizing and addressing non-physical forms of IPV within the context of modern technology and changing societal dynamics.

Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review guides researchers through the vast terrain of existing knowledge, illuminating the past to navigate the future.

It's a treasure trove of ideas, a mosaic of scholarly voices, and a canvas upon which new research paints its contributions.

The literature review doesn't just inform; it weaves the tapestry of context, connecting existing research threads into a coherent narrative.

In this intricate dance of ideas, researchers wade through the river of prior work, carefully selecting and integrating insights to build a bridge to their contribution.

Impacts of IPV

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) doesn't just cause immediate harm; its consequences can be long-lasting, taking a toll on victims' mental and physical well-being (CDC, 2012; Fleming et al., 2012; Devries et al., 2013). Coker et al. (2002) discovered that both men and women who were victims of physical IPV experienced negative health outcomes, including poor health, depressive symptoms, and substance abuse. Furthermore, they were at a heightened risk of developing chronic mental and physical illnesses. However, this study relied on anonymous self-reported surveys, which might lead to misclassification of reported health issues and the sequence of IPV victimization and health diagnoses.

Pico-Alfonso et al. (2006) identified that women subjected to physical or psychological partner violence suffered from increased rates and severity of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder compared to non-victimized women. The enduring impacts of IPV underscore why addressing this issue is vital; it extends beyond immediate injuries and can affect victims for a lifetime. This research highlights the importance of investigating the various methods perpetrators use to abuse their victims and how these methods can be identified and addressed. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the effect of physical IPV on mental health. Still, this research delves into the ramifications of psychological IPV, revealing that it can harm women's mental health in the absence of physical violence. This finding is significant as it challenges the misconception that IPV without physical abuse is less serious. However, it's crucial to note that this study primarily examined its impact on women, and the consequences of IPV may differ when considering male victims.

Stalking and Coercive Control

Tjaden & Thoennes' (1998) research reveals a concerning trend in stalking cases: the majority are perpetrated by individuals known to the victim, with half of all stalking cases involving current or former intimate partners. Recent research by Peterson, Liu, Merrick, Basile & Simon (2019) corroborates this, estimating that approximately 85% of stalking cases in the United States involve a current or former intimate partner. Tjaden & Thoennes (1998) also uncovered that stalking by an intimate partner tends to persist for longer durations than stalking by strangers. Furthermore, intimate partner stalkers display a greater inclination to carry out physical threats (Palarea, Zona, Lane & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 1999), assault their victims (James & Farnham, 2003), and re-offend even after legal intervention (Davis, Ace & Andra, 2000).

Coercive control is a pattern of controlling behaviours exhibited by an intimate partner that curtails an individual's independence, self-esteem, and decision-making autonomy (Hamberger, Larsen & Lehrner, 2017). An inspection of police responses to IPV in England and Wales revealed that officers often struggle to identify such patterns of abusive behaviour, especially when physical violence is not overt (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2014). Studies on coercive control suggest that it is more prevalent than physical violence and potentially more harmful. A study by Glass, Mangello, and Campbell (2004) discovered that, alongside factors such as recent separation and the presence of a weapon, the extent of control in a relationship was a more reliable predictor of homicide than the severity or frequency of physical violence.

Research conducted by Myhill & Hohl (2016) consistently identified behaviours indicative of coercive control in cases of IPV reported to the police. Coercive control was significantly associated with other IPV risk factors, far more so than physical violence. These findings suggest that focusing on identifying coercive control, rather than solely looking at physical violence, may be crucial in effectively assessing and addressing IPV before it escalates into physical violence.

Age and Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) isn't confined to adulthood; it also plagues young adults, particularly adolescents. Extensive research has explored dating abuse among this age group, with young women aged 16 to 24 exhibiting the highest prevalence of IPV (Rennison, 2001). In a college dating violence and abuse poll conducted by Knowledge Networks, 57% of college students expressed difficulty in recognizing dating abuse. Among those who had experienced it, a staggering 70% failed to realize they were in an abusive relationship at the time (Knowledge Networks, 2011).

A study by Simon et al. (2001) discovered that acceptance of physical violence in intimate partner relationships was less likely among individuals over 35 years old, indicating that older adults may be less tolerant of such behaviours. However, this study specifically focused on the physical aspects of IPV. It did not provide insights into whether similar trends would be observed for other forms of IPV, such as psychological abuse.

More recent research by Maquibar, Vives-Cases, Hurtig & Goicolea (2017) delved into professionals' perceptions of IPV among young people. Participants in the study described relationships among young adults as distinct from those in the adult population, with shorter durations and less clearly defined boundaries. They also noted that IPV among young adults appeared "normalized."

This study underscores how prior victimization experiences can influence current attitudes towards intimate partner violence. However, it primarily examined physical IPV, leaving questions about whether past victimization would have a similar impact on non-physical aspects of IPV, such as psychological abuse.

Gender and Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is often perceived through a gendered lens (Kubicek, McNeeley & Collins, 2015). Regrettably, female-to-male violence receives considerably less research attention than male-to-female violence despite studies indicating its more frequent occurrence than commonly believed (Strauss & Ramirez, 2007; Black et al., 2011).

Russell, Chapleau & Kraus (2015) conducted a study investigating the role of gender in perceptions of intimate partner violence. The study presented participants with a case summary of an assault, manipulating several factors related to gender and sexual orientation. Participants were then asked to assess to what extent the described behaviours could be considered abusive. The study revealed that female participants were more likely to view the assault as constituting abuse in comparison to their male counterparts. Surprisingly, the gender of the perpetrator did not significantly impact whether the incident was perceived as more or less abusive.

However, other research examining the influence of gender on IPV has found that violence perpetrated by males is often regarded as more severe (Seelau & Seelau, 2005). Additionally, males are frequently perceived as more violent than women in the context of IPV (Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward & Tritt, 2004). These contrasting findings underscore the complexity of how gender influences our perceptions of intimate partner violence.

Intimate Partner Violence and Technology

As previously mentioned, technology is rapidly advancing, with 95% of adults in the UK spending a significant amount of time online (ONS, 2019). While these technological advances offer numerous benefits, such as staying connected with loved ones and easy access to information and entertainment, they can also be misused. This misuse encompasses cyber-harassment, cyber-stalking, online sexual harassment, and abuse (Winkelman, Early, Walker, Chu, & Yick-Flanagan, 2015).

Researchers have categorized behaviours that constitute cyber-harassment and stalking, including:

- Monitoring their victim's emails.

- Sending threatening or insulting emails.

- Sending spam emails, including virus-laden emails.

- Using the internet to gather personal information to use against their victims.

- Excessive instant messaging, texting, or calling.

- Posting inappropriate messages online, such as on forums, social media pages, chatrooms, or blogs (Winkelman et al., 2015).

Woodlock's (2013) SmartSafe study delved into the issue of technology-facilitated stalking within the context of IPV. This study involved focus groups with IPV professionals and two online surveys: one targeted IPV support practitioners, and the other targeted IPV victims. The study revealed that 98% of support practitioners reported cases where perpetrators abused their victims through technology. This study shed light on how abusers employ technology to continue their abuse during and after the relationship, creating a sense of omnipresence in their victims' lives.

Research on non-physical aspects of IPV, such as stalking and coercive control, is crucial due to their long-lasting effects. Additionally, 76% of women who had an intimate partner murdered had been stalked before their murders (McFarlane, 1999). In recent years, research on IPV has expanded significantly, as has on cyberstalking and harassment (e.g., Ellison, 2003; Pittaro, 2007; Finn, 2004). However, there is a notable gap in research regarding individuals' ability to identify technology-facilitated intimate partner violence (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda & Calvete, 2015).

Zweig et al. (2015) conducted a questionnaire involving adolescents aged 12 to 18, revealing common forms of cyber abuse, including using the victim's social network without permission, sending messages to engage in unintentionally sexual behaviour or sharing sexual photos, and sending threatening messages. These findings indicate that technology-facilitated violence is present in individuals of various ages, although the study did not specifically investigate these behaviours in the context of intimate relationships.

Draucker & Martsolf (2010) reviewed interview transcripts of 56 young adults retrospectively reflecting on dating violence during their adolescence. They found that technology, including texting, calling, social networking sites, and instant messaging, was frequently used by participants' partners to abuse them verbally. Furthermore, technology facilitated the escalation of arguments and was employed to monitor the victim's behaviour. While technology was also used for seeking help during violent episodes with intimate partners, it often led to further conflict when victims attempted to call the police, friends, or family for assistance.

Burke et al. (2011) investigated the extent to which university students used technology to engage in acts of IPV. Their findings indicated that both male and female participants reported using technology to monitor their intimate partners, whether as the perpetrator or the victim. The study revealed that women were more likely to be perpetrators of monitoring their partner's emails, Facebook, and call history. At the same time, they were also more likely to experience their partners monitoring their emails, Facebook, and call history. It suggests that technology is increasingly becoming a means for individuals to perpetrate IPV. However, the self-report method employed in this study may introduce biases in participants' responses, particularly in terms of admitting to acts of controlling behaviour.

Schnurr, Mahatmya & Basche (2013) explored cyber abuse in IPV using an adapted version of Draucker & Martsolf's (2010) questionnaire for couples. Their results indicated that women were more likely to be perpetrators of both physical and non-physical intimate partner violence. Nevertheless, given the self-report nature of this questionnaire, biases may influence participants' willingness to admit to perpetrating IPV. This study underscores the fact that IPV is not a gender-specific social issue and indicates that women can be perpetrators of IPV to the same extent or even more so than males.

Attitudes

Attitudes and perceptions surrounding Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) held by the general public, law enforcement, and IPV workers are vital factors that influence the identification, reporting, and handling of IPV cases within the criminal justice system. Research reveals that people are more inclined to recognize certain behaviours as stalking when the perpetrator is a stranger as opposed to a partner or former partner (Scott, Rajakaruna, Sheridan & Sleath, 2013; Scott, Rajakaruna & Sheridan, 2013; Cass, 2011; Scott & Sheridan, 2011). Similarly, individuals are more likely to attribute alarm and fear of violence to the victim if the perpetrator is a stranger rather than a current or former partner (Scott, Rajakaruna, Sheridan & Sleath, 2013; Scott, Lloyd & Gavin, 2010; Scott & Sheridan, 2011; Sheridan, Gillett, Davies, Blaauw & Patel, 2003). However, this contrasts with research indicating that stalking is most frequently perpetrated by someone known to the victim and tends to be more protracted with potentially severe outcomes (Tjaden & Thoenennes, 1998; Napo, 2011; Peterson et al., 2019).

In the UK, controlling behaviour is defined as "acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance, and escape, and regulating their everyday behaviour" (The Serious Crime Act, 2015). Robinson, Myhill, and Wire (2018) examined attitudes and comprehension of coercive control among IPV professionals, as coercive control became a criminal offence in the UK in 2015. Their findings revealed varying levels of understanding among practitioners, with many failing to recognize patterns of coercive control. This study could be expanded to include the perspectives of clients of IPV professionals to determine if they demonstrate a better grasp of coercive control and are more adept at identifying abuse patterns.

Freed et al. (2017) explored digital technologies in the context of intimate partner violence. They conducted semi-structured interviews with IPV professionals, including police officers, case workers, support workers, and attorneys/paralegals, as well as focus groups with IPV victims. The study revealed that IPV professionals and victims felt ill-equipped to identify and address technology-facilitated IPV. This research underscores the necessity for further investigation into the role of technology in IPV, with a focus on educating professionals and victims to enable them to recognize and respond to technology-related abusive behaviours. It's important to note that while this study provides insight into the attitudes of IPV professionals and victims toward technology-facilitated abuse, it does not assess their ability to identify such behaviours.

Harway & Hansen (1993) and Hansen, Harway & Cervantes (1991) researched therapists' ability to identify patterns of IPV behaviour correctly. They used vignettes depicting IPV within a real couple undergoing therapy, with therapists tasked with conceptualizing the case. The results indicated that 40% of therapists failed to identify the conflict in the relationship before learning of the murder that occurred shortly after the therapy session.

A decade later, Dudley, McCloskey & Kustron (2008) replicated this study and found that only 13% of respondents failed to recognize the conflict in the relationship. This demonstrates an improvement in therapists' ability to detect and identify IPV behaviours. However, as these studies did not publish the vignette or questionnaire content, the specific types of IPV behaviours within the vignette remain unknown. Moreover, both studies only focused on therapists' ability to identify IPV, making their results less generalizable to the wider population.

Robinson, Pinchevsky, and Guthrie (2015) conducted a study using hypothetical vignettes illustrating patterns of physical and non-physical IPV behaviours. Police officers in the UK and the US were presented with these vignettes. Their findings indicated that police officers had a good understanding of IPV but also revealed that officers tended to expect physical abuse to be present in IPV cases. When physical abuse was absent, police officers were less likely to respond proactively. This study highlights how non-physical abuse is often overlooked by law enforcement, primarily because it does not align with their preconceived notions of what constitutes IPV. However, the study did not specifically evaluate whether officers recognized technology-facilitated IPV as abusive when it occurred in isolation.

While it is crucial to explore the attitudes of those within the criminal justice system regarding various forms of abuse, it is equally essential to consider the perspectives of other stakeholders. Victims of abuse are often less likely to approach the police than informal sources, such as family members or friends (Ashley & Forshee, 2005; Moe, 2007). Informal sources provide emotional support, practical assistance (such as shelter), and encouragement to leave an abusive relationship (Renzetti, 1988; Trotter & Allen, 2009). However, research suggests that negative reactions from informal sources can worsen the psychological well-being of victims and decrease the likelihood of reporting to the police or leaving the abusive relationship (Belknap, Melton, Denney, Fleury-Steiner & Sullivan, 2009; Goodkind et al., 2003; Mitchell & Hodson, 1983; Kennedy & Prock, 2018). Therefore, understanding public perceptions of IPV, including technology-facilitated abuse, is critical, as these individuals may form a crucial support network for victims.

Aims and Hypotheses

The first crucial step in addressing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is recognizing and acknowledging it. The existing literature underscores that non-physical IPV is the most prevalent form experienced by both men and women. To effectively combat IPV, it is essential that law enforcement, IPV professionals, and the general public can identify these behaviours. This study investigates the general public's ability to recognize patterns of non-physical IPV behaviours, in-person and through technology while examining potential associations with age, gender, and technology and social media usage.

Prior research has indicated that both IPV professionals and victims felt ill-equipped to identify technology-facilitated IPV (Freed et al., 2017). Thus, it is hypothesized that participants in this study will be more likely to recognize IPV when it occurs in person rather than through technology. Consequently, in-person IPV is expected to be perceived as more severe. Recognition of harassment is also anticipated to be higher when behaviours occur in person, with subsequent ratings of lower severity.

Previous research with a UK sample using a non-violent IPV vignette found that participants were more inclined to label the behaviours as harassment rather than abuse (Robinson, Pinchevsky & Guthrie, 2015). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the behaviours in both vignette conditions will be primarily categorized as harassment rather than IPV.

Studies have suggested that older individuals are less accepting of IPV behaviours and that younger people have less defined boundaries in their intimate relationships (Simon et al., 2001; Maquibar et al., 2017). Therefore, age is hypothesised to influence perceptions concerning behaviours, harassment, and IPV severity.

Previous research on IPV indicates that female participants are more likely than males to view IPV behaviours as abusive (Russell, Chapleau & Kraus, 2015). As a result, it is hypothesized that female participants will rate concerning behaviours, harassment severity, and IPV severity higher than male participants.

This study will also explore the impact of social media and technology usage on the perception of IPV behaviours. Notably, no previous research has delved into whether such usage affects how these behaviours are considered. Therefore, this study seeks to illuminate the potential influence of social media and technology usage on the perception of concerning behaviours, harassment, and IPV severity.

Methods

Methods are the blueprint of research, the recipe that turns questions into answers and curiosity into knowledge.

They are the tools wielded by researchers, the compass guiding them through the labyrinth of data and the path to uncovering hidden truths.

Methods are the secret handshake of the scientific community, ensuring that findings are not just opinions but rigorously tested and repeatable facts.

In this intricate dance of data collection and analysis, methods are the choreographer, shaping the research process into a graceful and meaningful performance.

Participant

The participants in this study were 178 adults, 124 females and 50 males, who completed an online survey. Of these 178, 36 were removed from the data due to an error in the survey, which showed them both or neither of the vignettes and questions. Therefore, the number of participants in this study is 142, 103 females and 39 males. The only exclusion criteria in this study were age – over 18 years only. This was due to the sensitive social issue discussed in the survey. Participants were asked to select an age range category (see Table 1). Participants were recruited using opportunity sampling. This study was approved by the ethics committee at Royal Holloway, University of London (see Appendix).

| Table 1 Sample Descriptives | ||||

| In-person | Technology Vignette | Total Sample | ||

| Gender | Male | 20 | 17 | 37 |

| Female | 48 | 53 | 101 | |

| Age | 18-24 | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| 25-34 | 13 | 10 | 23 | |

| 35-44 | 17 | 19 | 36 | |

| 45-54 | 12 | 22 | 34 | |

| 55+ | 13 | 9 | 22 | |

| Hours on social media per week | 0-10 | 26 | 26 | 52 |

| 10-20 | 35 | 39 | 74 | |

| 20+ | 7 | 5 | 13 | |

| Hours using technology per week | 0-30 | 27 | 23 | 50 |

| 30-60 | 27 | 35 | 63 | |

| 60+ | 14 | 12 | 26 | |

Materials and Procedures

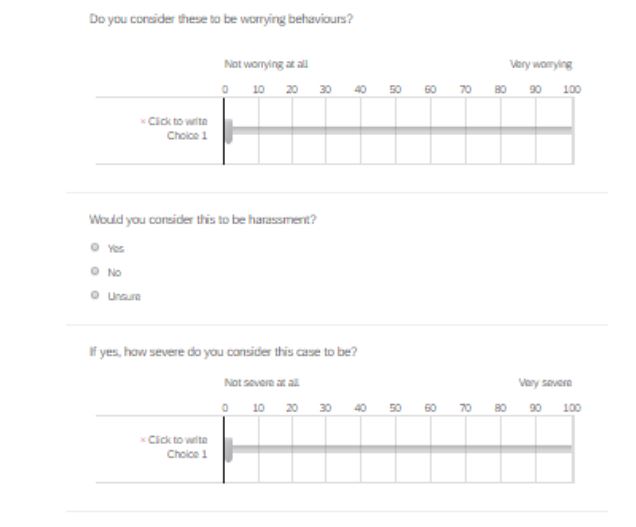

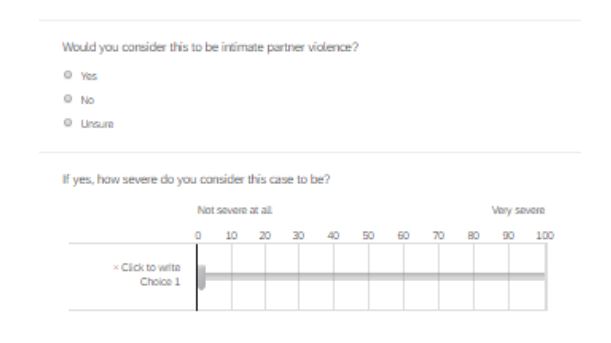

An online survey was conducted. As no studies have researched this specific aspect of IPV using vignettes, the researcher created an original survey instrument for this research. A short 4-item demographic questionnaire was used, asking the participant's age, gender, number of hours spent on social media per week, and amount of hours spent using any technology. They were also asked 5 questions about their perception of the vignette. These questions are as follows:

Do you consider these to be worrying behaviours?

Would you consider this to be harassment?

If yes, how severe do you consider this case to be?

Would you consider this to be Intimate Partner Violence?

If yes, how severe do you consider this to be harassment?

Questions 1, 3 and 5 are all rating questions, rated on a scale from 0 to 100. Questions 2 and 4 were multiple-choice questions with the possible answers of ‘Yes, ‘No’ or ‘Unsure’.

Participants were shown one of two vignettes of behaviours that constitute IPV according to UK legislation (CPS ?). In the first vignette, these behaviours are committed in person; in the other vignette, they are committed via technology. After being shown one of the vignettes, participants completed a questionnaire to ascertain the participant's perceptions of the vignette's behaviours. The vignettes in this study are hypothetical and were created for this study. The vignettes both contain IPV behaviours such as stalking, social isolation, invasion of privacy and financial abuse. The difference between the vignettes is that in one vignette, the IPV is perpetrated in person, and in the other, the IPV is perpetrated using technology. Each behaviour in one vignette matches the behaviour in the other. For example, in the in-person vignette, one of the behaviours was ‘Chelsea has, on numerous occasions, told Sam that he is not allowed to go out and see any of his female friends.’ This was matched in the technology vignette and contained the behaviour ‘Chelsea has also made Sam delete all his female friends from his social media accounts. Each behaviour included in the vignettes was based on IPV behaviours from case study interviews conducted for the ‘Using Law and Leaving Domestic Violence Projects’ (Douglas, 2020).

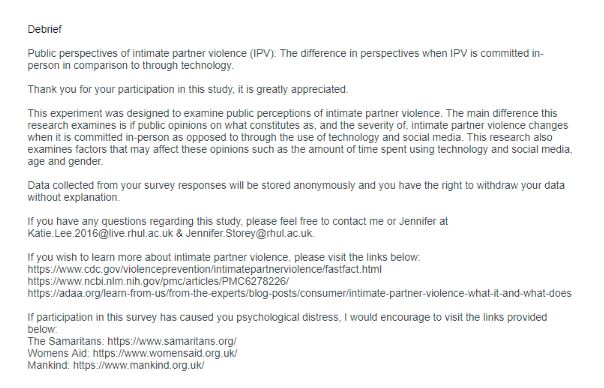

The participants recruited to participate in this study were informed via the social media platform Facebook and the instant messaging service WhatsApp. The link was accessible from participants' electronic devices and could be completed at their convenience. The participants clicked a link to volunteer to take part in the study. The survey was conducted using Qualtrics, an online survey-making tool. Once the participants clocked the link, they were taken to the information and consent page. The information sheet informed the participants of the nature of the study, what it consisted of, and anonymity, and they were free to withdraw at any time without an explanation (see appendix). The participants were then required to select either ‘I agree’ or ‘I disagree’. If ‘I disagree’ was selected, the questionnaire was automatically ended. If ‘I agree’ was selected and informed consent was given, the participant continued the questionnaire. This was the only question in the questionnaire which required a response. The rest of the questionnaire did not require the participant to give a response to continue. The first four questions were demographic. These were then followed by one of two vignettes, in-person or technology. The vignettes shown to the participants were random. Participants were then asked a series of questions on their perception of the behaviours in the vignettes and whether they considered them worrying, harassment and IPV. If they considered the behaviours harassment or IPV, they were asked to rate the severity. After the participants complete the questions on the questionnaire, they are taken to the debrief page, which explains the aim and purpose of the study.

Results

Results are the harvest of research, the culmination of countless hours, meticulous planning, and intellectual curiosity.

They are the revelations, the "Eureka" moments, where data transforms into insights, and hypotheses find their confirmation or refutation.

Results are the currency of scientific progress, the building blocks of knowledge that form the bedrock of future discoveries.

In the tapestry of research, results are the vivid threads that, when woven together, create a meaningful and illuminating pattern.

IPV Recognition and Severity

A series of chi-square tests of independence were conducted to analyse the relationships between vignettes shown to the participant and their perceptions of the vignette with alpha equal to .05 as a criterion for significance. The first chi-square tests analysed whether they considered the vignette to constitute IPV depending on what vignette they were shown. As shown in Table 1, a significant effect was found between which vignette the participant was shown and whether they considered the behaviours to be IPV χ2 (2, 138) = 7.87, p= .02. The effect size for this finding, Cramer's V, was medium, .24. This demonstrates that depending on how IPV is perpetrated, in person or via technology, will have some influence whether they determine the behaviours to be IPV or not. Participants who read the technology-facilitated IPV vignette were more likely to be unsure if the behaviours constituted IPV than participants who read the in-person IPV vignette. A Shapiro-Wilk test showed a significant departure from normality for IPV severity scores w(76) = .92, p=.00; therefore, non-parametric analysis was conducted. A Mann-Whitney U test found no significant difference between IPV severity scores in the in-person condition (Mdn = 80) compared to the technology condition (Mdn = 75), U=655, p=.51, ns.

| Table 1 Chi-square results show participants' perceptions of the vignettes. | |||||||

| In-person | Technology | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p | ||

| Harassment | Yes | 66 | 97 | 62 | 89 | 5.297 | .071 |

| No | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Unsure | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | |||

| IPV | Yes | 41 | 60 | 36 | 51 | 7.877 | .019 |

| No | 17 | 25 | 10 | 14 | |||

| Unsure | 10 | 15 | 24 | 34 | |||

Harassment Recognition and Severity

A chi-square test was conducted to analyse the relationship between the vignette shown to the participants and whether they considered the behaviours harassment. As shown in Table 1, no statistically significant effect was found χ 2 (2, 138) = 5.30, p= 0.7. A Shapiro-Wilk test showed a significant departure from normality for harassment severity scores w(127)=.85, p=.000. Therefore, a non-parametric analysis was conducted. A Mann-Whitney test found no significant difference in harassment severity scores in the in-person condition (Mdn = 82) compared to the technology condition (Mdn = 76), U=1887, p=.54, ns.

Age and worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity

A series of Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to examine the effect of age on worrying behaviour severity, harassment severity and IPV severity scores. Kruskal-Wallis tests were selected due to the violation of assumptions for a one-way ANOVA. The data passed assumptions for the Kruskal-Wallis tests.

A Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that there was a statistically significant difference in IPV severity scores between age groups H(4)=9.630, p=.047, with a mean IPV severity score of 22.54 for 18 to 24-year-olds, 34.46 for 25 to 34-year-olds, 42.05 for 35 to 44-year-olds, 43.47 for 45 to 54-year-olds and 46.27 for over 55-year-olds. The results of the Bonferroni posthoc test show no significant difference between IPV severity and any age group. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference in worrying behaviours or harassment severity scores between age groups H(4)=5.460, p=.243, H(4)=8.990, p=.061.

The two vignette groups were then analysed separately, in-person and technology, to see if age affects IPV severity scores and harassment severity scores. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference in IPV severity scores between age groups for both the in-person vignette condition and the technology vignette condition, H(4)=3.309, p=.508, H(4)=4.452, p=3.48. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between age group and harassment severity, H(4)=8.590, p=.072, H(4)=2.568, p=.632.

Gender and worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity

A series of Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to examine the effect of participant gender on the perception of worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity. A Mann-Whitney test showed no statistically significant difference in worrying behaviours scores for males (Mdn=100.0) and females (Mdn=100.0), U=1662.0, p=.37, ns. A Mann-Whitney test showed no statistically significant difference in harassment severity for males (Mdn=80.0) and females (Mdn=80.5), U=1546.5, p=.73, ns. A Mann-Whitney test showed no statistically significant difference in IPV severity scores for males (Mdn=80.0) and females (Mdn=75.0), U=462.0, p=.39, ns.

Several Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to analyse the effect of participant gender on worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity, analysing the technology condition and in-person condition separately. As can be seen in Table 3, no statistically significant effects were found.

Table 3 Summary of differences between males and females in both vignette conditions. | ||||||

| Male | Female | |||||

| Median | Median | U | p | |||

| Technology Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 100.0 | 98.0 | 432.5 | .99 | |

| Harassment Severity | 80.0 | 75.5 | 364.5 | .88 | ||

| IPV Severity | 81.0 | 71.0 | 72.0 | .16 | ||

| In-person Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 99.0 | 100.0 | 391.5 | .18 | |

| Harassment Severity | 85.0 | 81.5 | 410.5 | .75 | ||

| IPV Severity | 80.0 | 80.5 | 163.0 | .95 | ||

Social Media Usage

Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to analyse the difference in worrying behaviours scores, harassment severity scores and IPV severity scores depending on hours spent on social media per week.

A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent on social media and worrying behaviours score, H(2)=.62, p=.73, with a mean rank of 71.4 for less than 10 hours, 67.2 for 10-20 hours and 63.8 for over 20 hours. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent on social media and harassment severity score, H(2)=.25, p=.89, with a mean rank of 66.0 for less than 10 hours, 63.2 for 10-20 hours and 61.1 for over 20 hours. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent on social media and IPV severity score, H(2)=3.04, p=.22, with a mean rank of 43.2 for less than 10 hours, 37.5 for 10-20 hours and 27.4 for over 20 hours.

A series of Kruskal-Wallis tests were again conducted to see if there was any difference in each condition. As seen in Table 4, no statistically significant difference was found.

Table 4 Kruskal-Wallis shows differences between social media usage in both vignette conditions. | |||||||

| 0-10 | 10-20 | 20+ | |||||

| Mean rank | Mean rank | Mean rank | H | p | |||

| Technology Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 38.9 | 32.0 | 30.0 | .34 | .85 | |

| Harassment Severity | 33.0 | 29.9 | 29.7 | .10 | .95 | ||

| IPV Severity | 18.7 | 18.5 | 12.3 | 2.50 | .29 | ||

| In-person Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 33.2 | 35.7 | 33.6 | 2.37 | .31 | |

| Harassment Severity | 34.0 | 33.6 | 31.4 | .45 | .80 | ||

| IPV Severity | 24.3 | 19.6 | 15.25 | 1.01 | .60 | ||

Technology Usage

Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to analyse the difference in worrying behaviours scores, harassment severity scores and IPV severity scores depending on hours spent using technology per week.

A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent using technology and worrying behaviours score, H(2)=.01, p=.99, with a mean rank of 68.1 for less than 30 hours, 68.8 for 30-60 hours and 68.6 for over 60 hours. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent using technology and harassment severity score, H(2)=3.26, p=.20, with a mean rank of 71.2 for less than 30 hours, 62.6 for 30-60 hours and 55.3 for over 60 hours. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no statistically significant difference between hours spent using technology and IPV severity score, H(2)=2.70, p=.26, with a mean rank of 39.9 for less than 30 hours, 41.6 for 30-60 hours and x31.2 for over 60 hours.

A series of Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted again to see the difference in each condition. As shown in Table 5, no statistically significant difference was found.

Table 5 Kruskal-Wallis shows differences between technology usage in both vignette conditions. | |||||||

| 0-30 | 30-60 | 60+ | |||||

| Mean rank | Mean rank | Mean rank | H | p | |||

| Technology Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 38.8 | 33.2 | 30.7 | 1.80 | .41 | |

| Harassment Severity | 38.6 | 28.2 | 27.7 | 4.44 | .11 | ||

| IPV Severity | 17.6 | 20.1 | 27.7 | 2.05 | .36 | ||

| In-person Vignette Condition | Worrying Behaviours | 30.6 | 36.9 | 37.4 | 2.23 | .33 | |

| Harassment Severity | 34.2 | 35.7 | 28.3 | 1.44 | .49 | ||

| IPV Severity | 22.0 | 22.4 | 17.3 | 1.30 | .52 | ||

Discussion

This study provides new empirical evidence regarding individuals' perceptions of what constitutes IPV, specifically concerning whether it is perpetrated in person via technology. Previous research shows mixed results in abilities to identify IPV. Some studies have shown participants have a good understanding of what constitutes IPV, and others have shown a lack of knowledge. However, these studies have not looked at the specific difference between in-person perpetrated IPV and technology-facilitated IPV. Therefore, this study looks at participants' ability to worry about behaviours, harassment and IPV and how these change when the incidents occur in person compared to via technology. Overall, it is clear that the majority of individuals possess a good understanding of harassment and when behaviours would be considered worrying in intimate relationships. Most participants recognised the fictional vignettes as harassment regardless of whether they were shown the in-person or technology vignette. However, as shown in Table 1, only 60% of participants in the in-person condition and 51% in the technology condition recognised the behaviours as IPV. This suggests a general lack of knowledge concerning the behaviours that constitute IPV. One reason for the overall lack of identification of IPV behaviours may be the lack of physical violence in the study vignettes. Both focus on the non-physical aspect of IPV due to the nature of the study. Previous research suggests a dominant awareness of violence but less understanding of non-physical aspects of IPV, such as coercive control. (cite)

Another possible explanation for why IPV was recognised at a low rate may be the role of gender in the vignettes. Due to increasing research to support the fact that men can, and often are, victims of IPV, the vignette depicted a female perpetrator and a male victim. The vignettes both depict a female as the perpetrator of IPV. Research shows that individuals have a higher level of acceptance of female-perpetrated violence as opposed to male-perpetrated violence (cite). Previous research also shows that female victims of IPV are perceived as less blameworthy than male victims. IPV with a female victim is seen as more serious than when the victim is male (Stanziani, Newman, Cox & Coffey, 2020).

It was hypothesised that IPV will be recognised more when perpetrated in person than technology and will subsequently be rated more severely. This hypothesis was partially supported. The findings suggest that the way IPV is perpetrated will affect whether people identify it as IPV or not. As seen in Table x, 70% of the participants were ‘unsure’ whether the vignettes depicted IPV were in the technology vignette group. However, roughly half of the participants in both vignettes identified the behaviours as IPV. The participant's responses differed in the number of participants who were unsure about the vignettes. The findings suggest a lack of awareness or understanding of what technology-facilitated IPV consists of. These results are similar to those of Freed et al. (2017), who found that IPV professionals and victims felt they had inadequate knowledge regarding the use of technology in IPV. These results are also consistent with statistics from Knowledge Something, which found that 57% of college students said technology-facilitated dating abuse was difficult to identify.

Although awareness of IPV has continued to grow, these findings suggest IPV perpetrated via technology is still an area where people are uncertain. Research into technology-facilitated IPV shows that victims may justify these behaviours as acts of love. For example, Draucker and Martsolf (2010) found that participants justified controlling or monitoring behaviours as being motivated by care or concern. However, the majority of the participants recognised these behaviours were usually motivated by concerns about infidelity or insecurity in the relationship.

Of the participants who considered the vignette behaviours to be IPV, there was no difference in IPV severity scores between the in-person and technology conditions. This suggests that although individuals are more unsure of what constitutes a technology-facilitated IPV when recognised, they perceive the behaviours to be just as severe as when it is committed in person. This is consistent with previous research by

Harassment in-Person and via Technology

Secondly, it was hypothesised that harassment will be recognised more when perpetrated in person than in technology. This hypothesis was not supported. In both conditions, the behaviours were very similar in recognition rates for harassment. In addition, harassment was rated at a similar rate of severity when the behaviours were committed in person or via technology.

Our findings show the vast majority of the participants labelled the vignette as harassment, 97% of the participants were shown the in-person vignette, and 89% were shown the technology vignette (see Table 1). This suggests that most people are aware of harassing behaviours in intimate relationships. However, although the participants recognised the behaviours as abusive, this did not necessarily mean they thought it was enough to constitute IPV. One reason why participants may have identified the behaviours as harassment more than IPV may be due to the lack of physical violence in the vignette. Harassment is when a person acts in a way intended to cause another distress; this must occur more than once. This is arguably a much simpler term than IPV, which can often be surrounded by much confusion.

Thirdly, it was hypothesised that behaviours would be labelled harassment rather than IPV in both conditions.

Age

It was also hypothesised that age will impact how worrying behaviours are considered, as well as the identification and severity of IPV and harassment. This hypothesis was partially supported. The findings suggest that age affects how severe the participants rated the severity of IPV. The older the participants were, the more severe they rated the IPV.

One possible explanation for this finding may be adolescents' inability to recognise technology-facilitated IPV as serious. Glauber, Randel & Picard (2007) found that 78% of young people who have been harassed on social networking sites and 72% who reported being checked on repeatedly via technology did not disclose this to their parents. The most common reason for non-disclosure was they did not believe it was serious enough to justify disclosure. This finding, along with previous research, shows that young people are far less aware of the severity of IPV.

A possible explanation for why age influences the perceived severity of IPV may be due to young people’s inexperience in relationships. Age has been previously identified as a risk factor, and adolescents and young adults have been identified as the most at risk of IPV victimization (cite). With young age being a risk factor and young people being less able to identify IPV, this suggests a need for education on IPV for these age groups. Implementing educational programs for young people around healthy relationships and how to identify IPV may be the first step in reducing rates of dating violence. As this is an age when most individuals are first experiencing intimate relationships, if they are educated on how to identify and respond to IPV, it could prevent victimization in these crucial years. Also, as previous studies show that adolescent partner violence is strongly associated with experiencing intimate partner violence in adulthood (O’Leary et al. 1989; Cleveland et al. 2003), early education may prevent further victimization.

Gender

Findings show no difference between female participants and male participants for worrying behaviours rating, harassment severity rating or IPV severity rating. This is inconsistent with previous research by Russell, Chapleau & Kraus (2015), who found that IPV incidents were more likely to be rated as abuse by female participants than by male participants.

Societal perceptions of IPV are that it is a gendered issue; this has guided research perspectives which did not allow for the examination of male victimization. However, in recent years, there has been an increase in awareness of males being the victims of IPV. For example,

One possible explanation for the lack of significance may be the lack of males in the study. The participants in this study consisted of 37 males and 101 females. The findings were slightly skewed towards female participants perceiving worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity as less severe than for males. The small number of males in the sample may have affected the study’s power to gain a significant result.

Social Media and Technology

It was hypothesised that social media and technology users would impact the recognition and perceived severity of IPV, harassment, and worrying behaviours in both conditions. No previous research examined the association between social media usage and IPV identification or technology usage and IPV identification. The findings of this study show no association between the amount of time spent on technology or social media and the ability to identify IPV. There was also no association between social media or technology use and worrying behaviours, harassment severity and IPV severity in both vignettes. A possible explanation as to why no significant result was found may be due to the small sample size. Although there were 138 participants in total in this sample, due to independent measures, there were only 68 in the in-person condition and 70 in the technology condition.

Limitations

This is a foundation study into the different perceptions of IPV regarding whether it is committed in person or via technology, and further research should examine more appropriate participant samples in the context of technology-facilitated IPV, such as police and IPV professionals as these are the individuals who deal with these situations most frequently. Furthermore, research into educational professionals and their ability to identify technology-facilitated IPV and their responses to this IPV. This is crucial as this study and previous research suggest that young people may be less able to identify IPV than their adults. If teachers can identify the behaviours in these young people, they may be able to prevent IPV victimisation and perpetration.

Participants were not asked about their level of knowledge or history of IPV. This may have affected how they responded to the vignette. One study examining perceptions of IPV examined how prior experiences affected participants’ responses. They found that the greater the prior experience with IPV perpetration or victimization, the more normal they rated the IPV scenarios to be. Further research should explore whether the history of technology-facilitated IPV impacts an individual’s perception (Kuijpers, Blockland & Mercer, 2017).

Using vignettes in a study allows the participants to talk about the sensitive social issue of IPV from a non-personal perspective, which is subsequently less threatening and less likely to cause the participants harm. However, as both vignettes in this study lack physical violence, the vignette may not have been sensitive enough, resulting in less statistical significance in results and smaller effect sizes. Faia (1979) argued that using vignettes produces unrealistic results due to the lack of comparison to real life. Participants who read the vignettes are not involved in the situations as they would be in real-life situations.

One limitation of this study is that participants were not offered an opportunity to explain why they believed the vignettes did or did not constitute harassment or IPV. Further research should allow participants to give the reasoning for their response choice to identify a possible cause for the lack of identification of IPV.

References

Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Archer, J. (2006). Cross-Cultural Differences in Physical Aggression Between Partners: A Social-Role Analysis. Personality And Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 133-153. DOI: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_3

Ashley, O., & Foshee, V. (2005). Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. Journal Of Adolescent Health, 36(1), 25-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014

Baker, C., & Carreño, P. (2015). Understanding the Role of Technology in Adolescent Dating and Dating Violence. Journal Of Child And Family Studies, 25(1), 308-320. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0196-5

Belknap, J., Melton, H., Denney, J., Fleury-Steiner, R., & Sullivan, C. (2009). The Levels and Roles of Social and Institutional Support Reported by Survivors of Intimate Partner Abuse. Feminist Criminology, 4(4), 377-402. doi: 10.1177/1557085109344942

Black, M.C., Basile, K.C., Breitling, M.J., Smith, S.G., Walters, M.L., Merrick, M.T., Chen, J., Stevens, M.R. (2011). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS_report2010-a.pdf

Borrajo, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., Pereda, N., & Calvete, E. (2015). The development and validation of the cyber dating abuse questionnaire among young couples. Computers In Human Behavior, 48, 358-365. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.063

Burke, S., Wallen, M., Vail-Smith, K., & Knox, D. (2011). Using technology to control intimate partners: An exploratory study of college undergraduates. Computers In Human Behavior, 27(3), 1162-1167. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.010

Cass, A. (2011). Defining Stalking: The Influence of Legal Factors, Extralegal Factors, and Particular Actions on College Students' Judgments. Western Criminology Review, 12(1), 1-14. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/wescrim12&id=3&collection=journals&index=

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31292

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/172837.pdf

Clark, A. (2011). Domestic Violence, Past and Present. Journal Of Women's History, 23(3), 193-202. doi: 10.1353/jowh.2011.0032

Cleveland, H., Herrera, V., & Stuewig, J. (2003). Abusive Males and Abused Females in Adolescent Relationships: Risk Factor Similarity and Dissimilarity and the Role of Relationship Seriousness. Journal Of Family Violence, 18(6), 325–339. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/A:1026297515314.pdf

Coker, A., Davis, K., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H., & Smith, P. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine, 23(4), 260-268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7

Connolly, J., & McIsaac, C. (2011). Romantic relationships in adolescence. In M. K. Underwood & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence (pp. 180–203). Guilford Press.

Davis, K., Ace, A., & Andra, M. (2000). Stalking Perpetrators and Psychological Maltreatment of Partners: Anger-Jealousy, Attachment Insecurity, Need for Control, and Break-Up Context. Violence And Victims, 15(4), 407-425. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.15.4.407

Devries, K., Mak, J., Bacchus, L., Child, J., Falder, G., & Petzold, M. et al. (2013). Intimate Partner Violence and Incident Depressive Symptoms and Suicide Attempts: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Plos Medicine, 10(5), e1001439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439

Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria. (2014). Technology-facilitated stalking: findings and resources from the SmartSafe project. Victoria: Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267928015_Technology-facilitated_stalking_findings_and_resources_from_the_SmartSafe_project

Douglas, H. (2020). Using law and leaving domestic violence. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://law.uq.edu.au/research/our-research/using-law-and-leaving-domestic-violence-project/using-law-and-leaving-domestic-violence

Draucker, C., & Martsolf, D. (2010). The Role of Electronic Communication Technology in Adolescent Dating Violence. Journal Of Child And Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(3), 133-142. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00235.x

Ellison, L. (2020). Cyberstalking. In D. Wall, Crime and the Internet (1st ed., pp. 141-145). London: Routledge.

Emery, C. (2010). Examining an Extension of Johnson’s Hypothesis: Is Male Perpetrated Intimate Partner Violence More Underreported than Female Violence? Journal Of Family Violence, 25(2), 173-181. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9281-0

Faia, M.A. (1979) The vagaries of the vignette world: a comment on Alves and Rossi, American Journal of Sociology, 85, 951–54.

Finn, J. (2004). A Survey of Online Harassment at a University Campus. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 19(4), 468-483. doi: 10.1177/0886260503262083

Fleming, K., Newton, T., Fernandez-Botran, R., Miller, J., & Burns, V. (2012). Intimate Partner Stalking Victimization and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Post-Abuse Women. Violence Against Women, 18(12), 1368-1389. doi: 10.1177/1077801212474447

Freed, D., Palmer, J., Minchala, D., Levy, K., Ristenpart, T., & Dell, N. (2017). Digital Technologies and Intimate Partner Violence. Proceedings Of The ACM On Human-Computer Interaction, 1(CSCW), 1-22. doi: 10.1145/3134681

Fugate, M., Landis, L., Riordan, K., Naureckas, S., & Engel, B. (2005). Barriers to Domestic Violence Help Seeking. Violence Against Women, 11(3), 290-310. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271959

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behaviour: Theory, research, and practical implications (p. 3–22). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Glass, N., Manganello, J. and Campbell, J.C. (2004). Risk for Intimate Partner Femicide in Violent Relationships. DV Report, 9(2), 1, 2, 30-33

Glauber, A., Randel, J., & Picard, P. (2007). Tech Abuse in Teen Relationships Study. Fifth & Pacific Companies, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.breakthecycle.org/sites/default/files/pdf/survey-lina-tech-2007.pdf.

Goodkind, J., Gillum, T., Bybee, D., & Sullivan, C. (2003). The Impact of Family and Friends’ Reactions on the Well-Being of Women With Abusive Partners. Violence Against Women, 9(3), 347-373. doi: 10.1177/1077801202250083

Hamberger, L., Larsen, S., & Lehrner, A. (2017). Coercive control in intimate partner violence. Aggression And Violent Behavior, 37, 1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2017.08.003

Hansen, M., Harway, M., & Cervantes, N. (1991). Therapists' perceptions of severity in cases of family violence. Violence and Victims, 6(3), 225–235

Harway, M., & Hansen, M. (1993). Therapist perceptions of family violence. In M. Hansen & M. Harway (Eds.), Battering and family therapy: A feminist perspective (p. 42–53). Sage Publications, Inc.

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). (2015). Increasingly everyone's business: A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse (p. 55). Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC).

Home Office. The Serious Crime Act 2015 (2015).

Intimate partner violence in the UK - Office for National Statistics. (2019). Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/intimatepartnerviolenceintheuk

Jacquet, C. (2015). Domestic Violence in the 1970s. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2015/10/15/domestic-violence-in-the-1970s/

James, D., & Farnham, F. (2003). Stalking and Serious Violence. The Journal Of The American Academy Of Psychiatry And The Law, 31(4), 432-439. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7187918_Stalking_and_Serious_Violence/stats

Kennedy, A., & Prock, K. (2018). “I Still Feel Like I Am Not Normal”: A Review of the Role of Stigma and Stigmatization Among Female Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse, Sexual Assault, and Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(5), 512-527. doi: 10.1177/1524838016673601

King-Ries, A. (2011). Teens, Technology, and Cyberstalking: The Domestic Violence Wave of the Future?Teens, Technology, and Cyberstalking: The Domestic Violence Wave of the Future? Texas Journal Of Women And The Law, 20, 131-164. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1121&context=faculty_lawreviews

Knowledge Networks. (2011). 2011 College Dating Violence and Abuse Poll. Knowledge Networks. Retrieved from http://www.loveisrespect.org/pdf/College_Dating_And_Abuse_Final_Study.pdf

Krug, E., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/introduction.pdf

Kubicek, K., McNeeley, M., & Collins, S. (2014). “Same-Sex Relationship in a Straight World”. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 30(1), 83-109. doi: 10.1177/0886260514532527

Kuijpers, K., Blokland, A., & Mercer, N. (2017). Gendered Perceptions of Intimate Partner Violence Normality: An Experimental Study. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517746945

Maquibar, A., Vives-Cases, C., Hurtig, A., & Goicolea, I. (2017). Professionals’ perception of intimate partner violence in young people: a qualitative study in northern Spain. Reproductive Health, 14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0348-8

McCleary-Sills, J., Namy, S., Nyoni, J., Rweyemamu, D., Salvatory, A., & Steven, E. (2015). Stigma, shame and women's limited agency in help-seeking for intimate partner violence. Global Public Health, 11(1-2), 224-235. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1047391

McFarlane, J., CAMPBELL, J., WILT, S., SACHS, C., ULRICH, Y., & XU, X. (1999). Stalking and Intimate Partner Femicide. Homicide Studies, 3(4), 300-316. doi: 10.1177/1088767999003004003

Mitchell, R., & Hodson, C. (1983). Coping with domestic violence: Social support and psychological health among battered women. American Journal Of Community Psychology, 11(6), 629-654. doi: 10.1007/bf00896600

Moe, A. (2007). Silenced Voices and Structured Survival. Violence Against Women, 13(7), 676-699. doi: 10.1177/1077801207302041

Myhill, A., & Hohl, K. (2016). The “Golden Thread”: Coercive Control and Risk Assessment for Domestic Violence. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 34(21-22), 4477-4497. doi: 10.1177/0886260516675464

NAPO. (2011). Stalking and Harassment – a study of perpetrators. London: NAPO. Retrieved from https://www.napo.org.uk/sites/default/files/BRF22-11%20Stalking%20and%20Harassment%20-%20a%20study%20of%20perpetrators.pdf

Office for National Statistics. (2019). Internet access – households and individuals, Great Britain: 2019. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/latest

Office for National Statistics. (2019). Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2019. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingjune2019

O'Leary, K., Barling, J., Arias, I., Rosenbaum, A., Malone, J., & Tyree, A. (1989). Prevalence and stability of physical aggression between spouses: A longitudinal analysis. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 263-268. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.57.2.263

Palarea, R., Zona, M., Lane, J., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (1999). The dangerous nature of intimate relationship stalking: threats, violence, and associated risk factors. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 17(3), 269-283. doi: 10.1002/(sic)1099-0798(199907/09)17:3<269::aid-bsl346>3.0.co;2-6

Peterson, C., Liu, Y., Merrick, M., Basile, K., & Simon, T. (2019). Lifetime Number of Perpetrators and Victim–Offender Relationship Status Per U.S. Victim of Intimate Partner, Sexual Violence, or Stalking. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051882464. doi: 10.1177/0886260518824648

Pico-Alfonso, M., Garcia-Linares, M., Celda-Navarro, N., Blasco-Ros, C., Echeburúa, E., & Martinez, M. (2006). The Impact of Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Intimate Male Partner Violence on Women's Mental Health: Depressive Symptoms, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, State Anxiety, and Suicide. Journal Of Women's Health, 15(5), 599-611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599

Pittaro, M. (2007). Cyberstalking: An Analysis of Online Harassment and Intimidation. International Journal Of Cyber Criminology, 1(2), 180-197. Retrieved from http://cybercrimejournal.com/mpittarojccjuly2007.pdf

Preventing Intimate Partner Violence. (2019). Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html

Raphael Dudley, D., McCloskey, K., & Kustron, D. (2008). Therapist Perceptions of Intimate Partner Violence: A Replication of Harway and Hansen's Study after More than a Decade. Journal Of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 17(1), 80-102. doi: 10.1080/10926770802251031

Rennison, C., & Rand, M. (2003). Nonlethal Intimate Partner Violence Against Women. Violence Against Women, 9(12), 1417-1428. doi: 10.1177/1077801203259232

Renzetti, C. (1988). Violence in Lesbian Relationships. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 3(4), 381-399. doi: 10.1177/088626088003004003

Renzetti, C., & Miley, C. (1996). Violence in Gay and Lesbian Domestic Partnerships (1st ed.). Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Robinson, A., Myhill, A., & Wire, J. (2017). Practitioner (mis)understandings of coercive control in England and Wales. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(1), 29-49. doi: 10.1177/1748895817728381

Robinson, A., Pinchevsky, G., & Guthrie, J. (2015). Under the radar: policing non-violent domestic abuse in the US and UK. International Journal Of Comparative And Applied Criminal Justice, 40(3), 195-208. doi: 10.1080/01924036.2015.1114001

Rose, D., Trevillion, K., Woodall, A., Morgan, C., Feder, G., & Howard, L. (2011). Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: qualitative study. British Journal Of Psychiatry, 198(3), 189-194. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.072389

Russell, B., Chapleau, K., & Kraus, S. (2015). When Is It Abuse? How Assailant Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Protection Orders Influence Perceptions of Intimate Partner Abuse. Partner Abuse, 6(1), 47-64. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.6.1.47

Schechter, S. (1982). Women and male violence (pp. 209-240). Boston: South End.

Schnurr, M., Mahatmya, D., & Basche, R. (2013). The role of dominance, cyber aggression perpetration, and gender on emerging adults' perpetration of intimate partner violence. Psychology Of Violence, 3(1), 70-83. doi: 10.1037/a0030601

Scott, A., & Sheridan, L. (2011). ‘Reasonable’ perceptions of stalking: the influence of conduct severity and the perpetrator–target relationship. Psychology, Crime & Law, 17(4), 331-343. doi: 10.1080/10683160903203961

Scott, A., Lloyd, R., & Gavin, J. (2010). The Influence of Prior Relationship on Perceptions of Stalking in the United Kingdom and Australia. Criminal Justice And Behavior, 37(11), 1185-1194. doi: 10.1177/0093854810378812

Scott, A., Rajakaruna, N., & Sheridan, L. (2013). Framing and perceptions of stalking: the influence of conduct severity and the perpetrator–target relationship. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(3), 242-260. doi: 10.1080/1068316x.2013.770856

Scott, A., Rajakaruna, N., Sheridan, L., & Sleath, E. (2013). International Perceptions of Stalking and Responsibility. Criminal Justice And Behavior, 41(2), 220-236. doi: 10.1177/0093854813500956

Seelau, S., & Seelau, E. (2005). Gender-Role Stereotypes and Perceptions of Heterosexual, Gay and Lesbian Domestic Violence. Journal Of Family Violence, 20(6), 363-371. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-7798-4

Sheridan, L., Gillett, R., Davies, G., Blaauw, E., & Patel, D. (2003). ‘There's no smoke without fire’: Are male ex-partners perceived as more ‘entitled’ to stalk than acquaintance or stranger stalkers? British Journal Of Psychology, 94(1), 87-98. doi: 10.1348/000712603762842129

Simon, T., Anderson, M., Thompson, M., Crosby, A., Shelley, G., & Sacks, J. (2001). Attitudinal Acceptance of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. Violence And Victims, 16(2), 115-126. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.16.2.115

Sorenson, S. (2007). Adolescent Romantic Relationships [Ebook]. New York: ACT for Youth. Retrieved from http://www.actforyouth.net/resources/rf/rf_romantic_0707.pdf

Statista. (2020). Daily Internet users in Great Britain 2006-2019. Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/275786/daily-internet-users-in-great-britain/

Smith, S., Smith, D., Penn, C., Ward, D., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression And Violent Behavior, 10(1), 65-98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001

Straus, M., & Ramirez, I. (2007). Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior, 33(4), 281-290. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199

Trotter, J., & Allen, N. (2009). The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: Domestic Violence Survivors' Experiences with Their Informal Social Networks. American Journal Of Community Psychology, 43(3-4), 221-231. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9232-1

Truman, J., & Morgan, R. (2014). Nonfatal Domestic Violence, 2003–2012 (p. 1). The Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ndv0312.pdf

Vandello, J. A., & Cohen, D. (2004). When Believing Is Seeing: Sustaining Norms of Violence in Cultures of Honor. In M. Schaller & C. S. Crandall (Eds.), The psychological foundations of culture (p. 281–304). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Vogels, E. (2020). 10 facts about Americans and online dating. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/06/10-facts-about-americans-and-online-dating/

Vranda, M., Kumar, C., Muralidhar, D., Janardhana, N., & Sivakumar, P. (2018). Barriers to Disclosure of Intimate Partner Violence among Female Patients Availing Services at Tertiary Care Psychiatric Hospitals: A Qualitative Study. Journal Of Neurosciences In Rural Practice, 09(03), 326-330. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_14_18

Winkelman, S., Early, J., Walker, A., Chu, L., & Yick-Flanagan, A. (2015). Exploring Cyberharrassment among Women Who Use Social Media. Universal Journal Of Public Health, 3(5), 194-201. doi: 10.13189/ujph.2015.030504

Wolf, M., Ly, U., Hobart, M., & Kernic, M. (2003). Barriers to Seeking Police Help for Intimate Partner Violence. Journal Of Family Violence, 18(2), 121-129. doi: 10.1023/a:1022893231951

Zweig, J., Dank, M., Yahner, J., & Lachman, P. (2013). The Rate of Cyber Dating Abuse Among Teens and How It Relates to Other Forms of Teen Dating Violence. Journal Of Youth And Adolescence, 42(7), 1063-1077. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9922-8

Appendix

The appendix is like the backstage of the research performance, housing the supporting cast of data, charts, and supplementary information that make the main act shine.

It's the treasure trove of extra details, a repository of evidence and references, where interested readers can dig deeper and uncover the nuances.

In the grand narrative of a research paper, the appendix is the appendix, an essential yet often overlooked part, quietly holding the key to a fuller understanding.

Supervision Log

| Date | Items for Review | Actions from the Review Meeting | Supervisor Comments/Signature |

| 16/10/19 | Presentation | Think about more questions for the survey to have a more complex analysis to conduct | Jennifer Storey |

| 12/11/19 | Introduction | Research and see other vignette studies or any that relate to the current study | Jennifer Storey |

| 20/01/20 | The survey maker did not split participants into two groups | Try using a Qualtrics survey maker to see if this is possible | Jennifer Storey |

Information sheet and consent form

Debrief form

Debrief form

Demographic Questions

What gender do you identify as?

Male

Female

Other

I prefer not to say

What is your age?

18-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55+

How many hours do you spend on social media per week?

Less than 10

10-20

Over 20

How many hours per week do you spend using any technology?

Less than 30

30-60

Over 60

Vignettes

In-Person: Chelsea has been dating her partner, Sam, for 1 year. Chelsea frequently follows Sam to work in the morning to ensure he is not lying about where he is going. She also makes frequent trips to his work throughout the day. Chelsea has repeatedly told Sam that he is not allowed to go out and see any of his female friends. Sam has recently found out that Chelsea has been meeting with Sam’s friends and family without his knowledge and claiming that he is being physically abusive towards her. Chelsea will send private letters to Sam, including letters from his family, work, and bank statements. She has also demanded that Sam give her his PIN, bank card, and bank statements.

Technology: Chelsea has been dating her partner, Sam, for 1 year. Chelsea uses an app called ‘Find My Friends to ensure Sam is at work and continues to use this app throughout the day. Chelsea has also made Sam delete his female friends from his social media accounts. Sam has recently found out that Chelsea has been messaging Sam’s friends and family on Facebook, claiming that he is being physically abusive towards her. Chelsea will open Sam’s emails from family, work and his bank. She has also demanded that Sam give her his online banking information.

Questionnaire:

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?