Challenges of Encouraging Waste Reduction in Commercial Project within the Ghanaian Construction Industry

June 5, 2022

Monitoring and Assessment in Mathematics in Classroom

June 15, 2022 Download PDF File

Download PDF File

In dysfunctional families, childhood trauma thrives amid instability and neglect, fostering a collective vulnerability. This shared distress often culminates in drug abuse as a collective coping mechanism, perpetuating a cycle of dysfunction. Growing up in a dysfunctional family leaves an indelible mark on an individual's mental and emotional well-being. The intricate web of instability, neglect, and strained relationships within such households creates an environment ripe for the development of childhood trauma. Children exposed to constant conflict, emotional neglect, or inconsistent care may internalize these experiences, shaping their perception of self and the world around them. The lack of a stable foundation and nurturing relationships can lead to a profound sense of insecurity and vulnerability, setting the stage for enduring emotional scars that linger into adulthood.

159+ Quality Mental Health Dissertation Topics

In this blog, we will delve into the profound ways in which the dynamics of a dysfunctional family collectively influence the trajectory toward drug abuse. The coping mechanisms adopted in response to the chaos and emotional void within the family unit often manifest in destructive behaviours, with drug abuse becoming a pervasive outlet for numbing the pain of unresolved trauma. Understanding the interconnectedness of dysfunctional family dynamics, childhood trauma, and the cycle of substance abuse is essential to unravelling the complexities that perpetuate this detrimental cycle.

Introduction

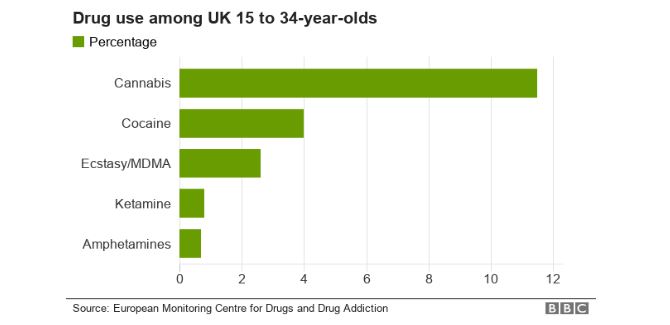

This report delves into the impact of childhood trauma on substance abuse, concurrently examining the influence of dysfunctional family dynamics on the development of drug addiction in children. While explicating this connection, the study underscores the heightened susceptibility of children from dysfunctional families to succumb to drug addiction. According to Griffin et al. (2019), the typical onset of drug initiation occurs during late puberty to early adulthood, underscoring the pivotal role of pre-adulthood as a formative stage for interventions and education to deter substance abuse. Grecu, Dave, and Saffer (2019) concurred, emphasizing that the initiation of drug abuse at an early age could exert lasting effects on an individual's life, influencing subsequent drug use habits. The accompanying chart illustrates a significant prevalence of drug abuse among young adults, particularly during festive periods.

Verdejo-Garcia et al. (2018) concurred with the findings depicted in Figure 1, emphasizing the imperative to identify the factors contributing to the elevated prevalence of substance abuse among individuals. Brown and Shillington (2017) asserted that individuals who experienced traumatic childhoods are at a heightened risk of engaging in substance use. However, there is a notable gap in research examining the correlation between childhood trauma and the initiation of substance use in the early stages of adulthood. Kirsch, Nemeroff, and Lippard (2020) contended that there is a scarcity of studies specifically investigating the role of traumatizing events during childhood, such as family difficulties, in substance abuse initiation during pre-adulthood.

In collective findings, it has been reported that aspects of youth trauma correlate with the period preceding the onset of drug and alcohol use, with young men reporting heavier alcohol use as a coping mechanism for experiences such as rape and engaging in drinking behaviours (Teese, 2018).

Childhood Trauma

According to Zaykowski (2019), childhood trauma can occur when individuals face overwhelming negative experiences during their early years. Allbaugh et al. (2018) emphasized that limited interaction with others, particularly in cases of restricted social engagement, can have profound adverse effects on a child. Similarly, Van der Kolk (2017) concurred, noting that negative interactions such as abuse, neglect, and violence during childhood can lead to traumatic experiences, which can be characterized as relational trauma, particularly in dysfunctional families.

In contrast, Miller (2019) argued that incidents like illness, war, regional distress, accidents, natural disasters, and the unexpected loss of loved ones during early years are primary factors that can traumatize individuals. Similarly, Chung et al. (2018) discussed how witnessing distressing events involving family, friends, or even strangers can contribute to childhood trauma. Bryant‐Davis et al. (2017) added that exposure to media depicting violence can also induce trauma in young individuals. Vogt (2019) argued that while such media may upset and frighten children, it may not necessarily traumatize them. Kitta et al. (2016) concurred, stating that situations like domestic violence, parental divorce, or a discordant family environment can be more emotionally scarring for children. Regardless, to understand the connection between childhood trauma and drug abuse, it is crucial to examine the various factors that contribute to such trauma among children.

Causes of Childhood Trauma

Childhood trauma can stem from various sources, including exposure to domestic violence, parental separation, or an unstable family environment. Additionally, external factors like accidents, natural disasters, and unexpected loss can contribute to the development of childhood trauma.

Abuse

Abuse has been identified as a significant contributing factor to childhood trauma, with emotional and physical maltreatment serving as crucial indicators (McQueen et al., 2018). Wekerle et al. (2018) conducted a study comparing individuals with a history of childhood trauma to healthy counterparts, highlighting emotional mistreatment as the foremost indicator of childhood trauma. Oshri et al. (2017) observed higher levels of emotional mistreatment and neglect in women with a history of childhood trauma compared to those in healthy control groups. Bentovim (2018) argued that physical and sexual abuse stands out as the primary cause of childhood trauma.

Neglect

Krüger and Fletcher (2017) demonstrated that childhood emotional neglect serves as a predictor for childhood trauma in women. Similarly, Akbey, Yildiz, and Gündüz (2019) uncovered an association between childhood neglect and adult dissociation. Moreover, childhood trauma can perpetuate a negative cycle. Cecil et al. (2017) identified childhood trauma as a factor contributing to individuals' future negligence towards children. Marshall et al. (2018) concurred, noting that individuals with a history of childhood trauma may have positive intentions towards children; still, their past experiences hinder their ability to provide the necessary security for children to thrive and establish a meaningful bond with them.

Violence

Izaguirre and Cater (2018) asserted that violence has detrimental effects on children and young adults. Being subjected to abuse or mistreatment by adults, facing bullying from peers, witnessing aggressive behaviour at home, or observing a crime can be profoundly destructive for them. Cutuli, Alderfer, and Marsac (2019) concurred, noting that while many children exposed to violence may develop social, emotional, or learning difficulties, it's not a universal outcome. Rosen et al. (2018) supported this perspective, stating that experiencing or witnessing violence can be identified as a significant factor contributing to both mental and physical health issues in children, serving as a major cause of trauma.

The Effects of Childhood Trauma

Childhood trauma can have lasting repercussions, manifesting in social, emotional, and cognitive challenges for individuals. Additionally, it is often linked to adverse health outcomes, contributing to both mental and physical health issues throughout the lifespan.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Many children encounter distressing incidents (Rosen et al., 2018), and while most may initially struggle, they typically return to normal functioning relatively quickly. However, Cook et al. (2017) contended that children exposed to accidents, abuse, or violence are more susceptible to developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Those with PTSD may frequently re-live the trauma and avoid reminders of it (Powers et al., 2016). Mergler et al. (2018) concurred, noting that children with PTSD may also exhibit issues such as fear, depression, anxiety, aggressive behaviour, self-harm tendencies, a preference for isolation, low self-esteem, and trust issues.

Prolonged Health Issues

Negative interactions, incidents, or blunt trauma can impact both the psychological and physical development of affected children (Cohen, 2017). Turner et al. (2017) affirmed that adverse events during childhood can have long-lasting consequences. Craig et al. (2017) suggested that more adverse childhood experiences increase the likelihood of health issues later in life. Libre et al. (2017) concurred, noting that childhood trauma may predispose children to health problems such as asthma, depression, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Valles, Harris, and Sargent (2019) further emphasized that trauma originating from dysfunctional family dynamics, including physical and sexual abuse, as well as parental mistreatment, significantly contributes to mental disorders in young adults. These psychological issues may lead to suicidal tendencies, depression, and panic attacks. In essence, the enduring impact of these trauma sources extends to both the mental and physical well-being of a child. As children cope with trauma, some may turn to drug consumption as a means of diversion, and this coping mechanism can persist into adulthood, underscoring the link between childhood trauma and the initiation of drug abuse.

Treatment for Childhood Trauma

Effective treatment for childhood trauma often involves a combination of therapeutic interventions, including trauma-focused psychotherapy and counselling, aimed at helping the child process and cope with the traumatic experiences. Additionally, a supportive and nurturing environment, coupled with the involvement of caregivers, plays a crucial role in fostering the child's emotional healing and resilience.

Injury Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT)

Several evidence-based treatments have demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating the consequences of childhood trauma (Cohen, Deblinger, and Mannarino, 2018). Neelakantan, Hetrick, and Michelson (2018) affirmed that one such evidence-based treatment is Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT). TF-CBT, a structured intervention comprising 16-20 sessions, is designed for children aged 4-21 and their caregivers who have undergone traumatic experiences, addressing the enduring effects of trauma (Runyon et al., 2019).

Intellectual Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)

Cognitive-behavioural intervention, implemented within school settings, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms and mitigating psychosocial issues in children who have experienced trauma (Thompson and Kaufman, 2019). Haas (2018) concurred, emphasizing the increasing recognition of schools as vital settings for delivering services to safeguard children's physical and mental health. This treatment approach is deemed crucial in addressing post-traumatic stress in children.

Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI)

CFTSI, a preventative model spanning 4-6 sessions, is designed for children aged 7 to 18 (Epstein et al., 2017). The aims of CFTSI include reducing the negative effects of a traumatic event, enhancing communication between guardians and children, and equipping children with skills to cope with the aftermath of trauma (Oliver and Abel, 2017).

Trends in the Prevention of Childhood Trauma

As Haas (2018) emphasizes, there is a crucial need to prevent childhood trauma through established practices proactively. An interdisciplinary team is formed, consisting of experts from school emergency, safety, and mental health departments, as highlighted by McElvaney and Tatlow-Golden (2016). Ogden and Hagen (2018) support this approach, asserting that the team collaborates to ensure consistent implementation of prevention, preparedness, and intervention activities to reduce the likelihood of trauma. This structured framework not only addresses the needs of children effectively but also provides a supportive network crucial for students to build resilience and recover from trauma.

According to Higgins, Kaufman, and Erooga (2016), establishing a supportive community that offers stability and consistency is vital for students constructing defence mechanisms and potential healing from trauma. To facilitate effective intervention in cases of childhood trauma, it is essential to provide training on how trauma impacts children, fostering awareness, sensitivity, and improved identification of those who may require additional support. All staff should undergo training and be reminded to be vigilant in recognizing signs, typical behaviours, and trauma responses often exhibited at various developmental stages (Banitt, 2018).

The Need for Trauma-Informed Practice in Social Work

In the field of social work, special attention is required for patients dealing with trauma. Cicchetti and Banny (2014) emphasize that children who have experienced trauma may not readily accept care from medical professionals, necessitating a nuanced approach from social workers. Recognizing that 66%-94% of college-aged students have encountered trauma at some point in their lives (Levenson, 2017), there is a growing need for adaptation within the current social care system.

Childhood Care and Development

Addressing childhood trauma involves acknowledging the absence of a sense of safety in affected children, leading to a lack of trust in social workers' ability to help. Knight (2015) proposes that social workers need a comprehensive understanding of clients' issues, including the history and potential impact of trauma, to foster effective intervention. Failure to respond empathetically to trauma survivors can result in negative interactions, discouraging clients and hindering the healing process (Duffell and Basset, 2016).

Social workers must recognize that individuals with traumatic childhoods may resist methods that remind them of their trauma. Unfortunately, at times, social workers may unintentionally respond in a manner perceived as dismissive, judgmental, or disapproving (Chamberlayne and Smith, 2019). Consideration should be given to the possibility that those displaying challenging behaviours may be the ones in greatest need of post-traumatic therapy (Corrigan and Hull, 2018). Social workers must reflect on how their beliefs, values, perspectives, and experiences may impact client interactions, aiming to minimize potential barriers in the therapeutic process.

Dysfunctional Families and Drug Abuse

Dysfunctional families are a significant source of trauma and abuse for children, often extending into adulthood. Characterized by strained parent-child relationships, physical punishments, parental conflicts in the presence of children, and an overall violent atmosphere at home (Karson and Sparks, 2013), these dysfunctional households frequently result in severe complications for the children in their later lives, potentially contributing to drug abuse. Wu and Slesnick (2019) conducted a study to explore the correlation between adult drug abuse and dysfunctional family backgrounds. Through interviews with children from such environments, the study revealed that children of parents with drug or alcohol addiction have a significantly higher likelihood of developing addiction themselves unless proper intervention is implemented.

Stages of Dysfunctional Drug Abuse and its Impact

Drug addiction is not a simple single-step procedure; it is complicated with several cognitive and psychological factors involved. There are three stages of becoming an adult: binge and intoxication, withdrawal, and compulsory drug use (Crews et al., 2017). In the binge stage, the person tries drugs for the first time, whereas during withdrawal, it becomes harder for the person to avoid using, and in the final stage, the person becomes a compulsive drug addict. In the case of dysfunctional drug addicts, as the stages progress, their mental and physical health deteriorates as well. This impacts the person’s overall well-being and increases the tendency of the person to develop depression and attempt suicide (Brockie et al., 2015).

Current Use of the Drug Among Young Adults

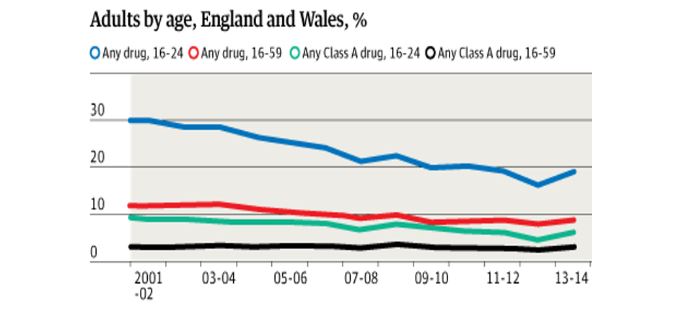

According to the study by Aldridge, Measham, and Williams (2013), the use of drugs among young adults has been common in recent years because such groups can easily access the drugs. Moreover, the research of Wilens et al. (2011) highlighted that individuals between the ages of 18-22 are considered young adults. Humensky's (2010) study also indicated that young adults are more prone to using drugs than older adults. According to Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han (2016), the common drugs young adults consume are alcohol, tobacco, and marihuana. In contrast, the study by Bachman et al. (2013) and Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han (2016) found that ecstasy and cocaine are the most common kinds of drugs consumed by young adults. Furthermore, the report of BBC News. (2019) highlighted that some records of drug use among young adults began in 1996 in the UK.

Additionally, a similar study identified that, with time, the drug use rate has kept increasing among young adults (BBC News. 2019). Also, it has been highlighted that the use of Class A drugs has been significantly increasing among young adults in the UK (Wilens et al. 2011). Approximately 8.7% of young adults were using Class A drugs in 2018; around 10.4% of individuals lie in the age bracket of 20-24 (BBC News. 2019). In the research of Humensky (2010), the author indicated that around 3000 young adults die due to substance abuse. Most deaths were caused by opiate-based drugs known as heroin (Aldridge, Measham, and Williams, 2013; Bachman et al., 2013). However, Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han (2016) identified that death from the use of cocaine has doubled within the last three years among young adults in the UK.

Reasons for High Drug Use Among Young Adults

The study by Kong et al. (2015) contemplated that multiple reasons encourage young adults to use drugs. A similar study identified that young adult tends to increase the use of drug medications due to significant level of depression and stress (Kong et al. 2015). Humensky (2010) survey supported the idea by highlighting that stress and depression in the teenage years are primary factors that raise drug use among young adults. Additionally, the research of Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han (2016) considered the bonding experience and boredom to be a reason that increased the frequency of drug use among young adults. However, the study by Cotto et al. (2010) and Aldridge, Measham, and Williams (2013) contradicted the argument by stating that lower self-esteem and other mental issues have been one of the prominent reasons that raised the use of drugs among young adults.

While the research of Redonnet et al. (2012) and Wilens et al. (2011) asserted that weight loss and curiosity for trying drugs had been the major reasons for increased drug consumption among adults, furthermore, the study by Hanson et al. (2011) indicated that peer pressure inclined individuals to use the drug at a young age that is consequently increasing the use of the drug when those individuals become young adults. In contrast, Bachman et al. (2013) research specified that the family history of drug addiction and genetics played a primal role in increasing the drug dosage among young adults. Moreover, the research of Kong et al. (2015) stated that most young adults were exposed to now or never situations due to addiction levels to using certain drugs. At the same time, research by Ramo et al. (2010) specified that young adults increase the use of drugs to get better in academics and sports.

External Factors

Drug dependence based on a person’s physical needs, not psychological or emotional ones, is initiated through external factors, such as exposure to drug sources (Müller, 2018). Usually, violent or abusive factors are considered initiators of drug use, but it is not applicable in functional usage. According to Askew (2016), in practical usage of drugs, people start taking drugs from friends or peers for recreational purposes, but as time passes, they become addicted. Therefore, a previously non-addict person on exposure to drugs involuntarily or unintentionally starts administering medications daily.

Furthermore, Cormack and Carr (2013) add that this transition happens in two main stages: tolerance and withdrawal. Tolerance means that the individual becomes immune to smaller doses of drugs, and slowly, the number of dosages increases. At the same time, withdrawal means that the person stops considering drug abuse as a problem and accepts it without trying to stop it. Thus, functional drug abuse is based on a person's physical needs, and with time, the person becomes entirely dependent on drugs.

Dysfunctional Families

Dysfunctional families tend to alter a person’s emotional state, which may force that person to become a drug addict as an adult. Wang, Zhang, and Zhang (2017) explain that a dysfunctional attitude in a person causes them to look at themselves, others, and their future from a very pessimistic viewpoint. This makes the person susceptible to depressive behaviours and an increased tendency to administer drugs to overcome such depressive episodes. Based on this definition, dysfunctional abuse is very different from functional abuse, as one is based on emotional needs while the other is based on physical conditions. This aspect highlights the influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse.

Another study by Clarke et al. (2012) believes that a person can only acquire a dysfunctional attitude when social pressures and family or friends are abusive and violent. According to the study, a person may not have depression; however, the behaviour of close loved ones can force the person to develop a dysfunctional attitude, which consequently increases the ability of a person to use drugs. Hence, drug abuse initiated by dysfunctional families causes a person to need to use drugs to overcome emotional or psychological stresses.

Factors Associated with Dysfunctional Families Promoting Drug Addiction

Drug addiction or abuse is a social disease that has both physical and psychological implications on the person. Pourallahvirdi et al. (2016) believe that the determinants of drug abuse play a crucial role in the long-term addiction and health planning of the drug addict. Several factors can encourage or force a person to start administering drugs, as given below:

Psychological Factors

One major psychological factor that exposes a person to drugs and ensures that the person fails in rehabilitation is coping mechanisms and a sense of responsibility (Petrova et al., 2015). A person with a sensitive coping mechanism can easily be engaged in illicit activities of taking drugs, and the absence of a sense of responsibility fuels this habit. Another factor that encourages drug usage is psychological disorders like anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, etc. These diseases can become underlying problems that motivate a person to inject drugs to escape the realities of emotional stress.

Furthermore, among psychological disorders, childhood trauma is a major instrument in forcing people in adulthood to take drugs. Mandavia et al. (2016) discuss the role of memories of trauma and abuse that people try to escape through drugs. Therefore, among the psychological factors, escapism is very important to consider as an initiator of drug abuse. On the contrary, Tang, Tang, and Posner (2016) believe that drug abuse is not from abusive relationships but rather the person’s violent behaviour. The study correlates anger and hostility within a person as factors that lead to drug abuse. Therefore, these studies agree that there is an enormous intensity of the influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse.

Socio-Demographic Factors

Several social and demographic factors determine a person’s attitude and behaviour towards addictive substances like drugs, alcohol, and others. Degenhardt et al. (2017) discuss the role of certain cultural norms that require a person to administer medications and, more importantly, the culture found within mafia or criminal organizations that forces all its members to use drugs. Another aspect is religion, as certain religious practices make it compulsory for the followers to use drugs.

Davenport and Pardo (2016) use the example of Rasta and Rastafari as a Jamaican tribe that conducts certain worshipping rituals after the administration of cannabis. The study discusses that such practices introduce drug usage to a person and, in the long run, make them an addict. However, in the current digital age, cultural and religious norms are as effective as the influence of social media. The study by Kim et al. (2017) discussed the role of social media websites in normalizing drug addiction among young adults and children.

Such practices expose individuals to drug abuse, even though they may not be directly linked to any psychological or social factors that cause drug abuse. Another aspect of socio-demographic drug abuse that is not much discussed in the literature is the geographic location (Degenhardt et al., 2017). If a country or city is near a major producer of drugs, then people in that area are bound to be exposed more and become drug addicts.

Economic Factors

Although depleting economic factors are often considered a consequence of drug abuse, as stated in the research of Yang and Xia (2019), drug abuse leads to low cash inflow, as the person has minimum to no source of earning and falls into poverty. However, this viewpoint has shifted, as economic factors are now considered the cause of drug abuse. A study carried out by Carpenter, McClellan, and Rees (2017) found that as soon as economic conditions in a country declined, drug usage within that region increased manifold. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that economic conditions and drug abuse have an inverse relationship, and the economy must be developed to tackle drug addiction. Similarly, this applies on a smaller scale of individual economic means. A person’s economic decline initiates depression and a pessimistic point of view, which results in a higher tendency to use drugs.

Factors Influencing Drug Use Among Young Adults in Today's World

In today's world, factors influencing drug use among young adults include societal pressures, peer influence, mental health challenges, and easy accessibility to substances. Additionally, environmental stressors, such as dysfunctional family dynamics and exposure to traumatic experiences, can contribute to the vulnerability of young individuals to engage in drug use.

Exploring the Impact of Video Games on Mental Health

Family History of Addiction

The research of Pilatti et al. (2014) identified that one of the significant factors that influence the use of drugs among young adults is a family history of addiction. A similar author added that genetic predispositions substantially influence young adults to try the drug for the first time (Pilatti et al. 2014). Additionally, the research of Acheson et al. (2011) emphasized that a close family member imposes a greater risk on young adults for using the drug. However, the research of Cservenka (2016) and Richardson et al. (2013) indicated that complicated environments at home, such as child abuse by family members, influence young adults to use drugs in today’s world. Although, the research of the Mayo Clinic. (2017) The weak bond among family members highly encourages young adults to develop drug addiction.

Mental Health Disorder

According to the study by Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han (2016), multiple psychological disorders at a young age tend to increase drug use among young adults in recent years. A similar author added that depression is a significant factor that increases drug use among young adults (Mojtabai, Olfson, and Han, 2016). Moreover, the Mayo Clinic (2017) study indicated the causes of depression, such as bad relationships, high work pressure, and low self-esteem, that influence young adults to use drugs. Additionally, the study by Pilatti et al. (2014) highlighted that hyperactivity disorder or attention deficit disorder is among some of the factors that encourage a young adult to drug use. A similar author added that hyperactivity disorder or attention-deficit clouds young adults' judgment regarding what is morally right and wrong, which consequently creates a habit of substance abuse among young adults (Pilatti et al. 2014).

Peer Pressure

The research of Iwamoto and Smiler (2013) indicated that in recent years, peer pressure has influenced drug use among young adults. Additionally, the study by Cservenka (2016) highlighted that friends are the most common element of peer pressure as they are major motivators for letting one try the drug for the first time. Thus, this leads to addiction to drug use until an individual becomes a young adult, thereby confirming the influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse.

Drawbacks of Drug Use Among Young Adults

The drawbacks of drug use among young adults encompass potential long-term health consequences, impaired cognitive function, compromised academic and professional performance, and an increased risk of addiction. Additionally, substance abuse can strain interpersonal relationships, hinder personal development, and contribute to legal and financial repercussions for young individuals.

Infectious Diseases

According to Fig. 2, it has been demonstrated that there is an increase in the use of drugs among young adults, specifically in England and Wales.

Platt et al. (2017) agreed with the statistics while highlighting that the utilization of used and contaminated injections is an essential transmission course for both HIV and hepatitis C. Expanding infusion medication use has set new populaces, including youngsters, in danger. The ease in the availability of drugs and the failure of the narcotics department to regulate the drug supply and use has resulted in the occurrence of blood-borne contaminations, including hepatitis B infection and hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency infection (HIV), and microorganisms that cause heart diseases (Williams,2019).

Poor Mental Health

All dysfunctional drugs, such as nicotine, cocaine, cannabis, and others, influence the brain activities of individuals (Vergara et al., 2018). Morrall, Worton, and Antony (2020) agreed and stated that drug use among young adults might be wilful. However, these drugs harm the mental health of individuals. This can change the brain's performance, affecting the individual's capacity to make decisions or perform routine actions (Hobkirk et al., 2019). It can prompt extreme yearnings and habitual medication use. After some time, this conduct can transform into substance reliance or medication and liquor dependence (Erickson, 2018).

Importance of a Healthy Childhood for a Better Later Adult Life

According to the study by Milteer, Ginsburg and Mulligan (2012), healthy childhood plays a significant role in improving a child's quality of adult life. A similar author highlighted that a healthy childhood assists an individual in achieving their lifetime goals (Larkin, Felitti and Anda, 2014). According to Piotrowska et al. (2017), parents' behaviour is one of the many active factors in providing a healthy childhood. Kiesel, Piescher, and Edleson (2016) stated that students with a less stressful home environment show good academic progress. Moreover, the study by Larkin, Felitti and Anda (2014) indicated that healthy childhood minimises the risk of developing chronic disease later in adulthood.

The study by Cook et al. (2017) highlighted that a healthy childhood considerably minimises the probability of mental disorders during the adult stage. McQueen et al. (2018) agreed and stated that children prone to traumatic childhood are more likely to develop social anxiety and mental disorders in adulthood. Furthermore, the research of Kitta et al. (2016) emphasised that the physical health of individuals declines with a slower pace of a child having a healthier childhood than an individual having a traumatic childhood. In contrast, the research of (Craig et al. 2017).

Also, the dissertation of Larkin, Felitti and Anda (2014) considered healthy childhood a major determinant that minimises the risk of metabolic disorder in adulthood. According to the study of Iwamoto and Smiler (2013), self-motivation and higher self-esteem are found among adults having a healthier childhood. In contrast, the study of Milteer, Ginsburg and Mulligan (2012) regarded that a healthier childhood significantly increases the morale of an individual towards life, such as the perception of higher life expectancy.

Chapter Summary

A literature review has been provided concerning childhood trauma experiences and their role in developing dysfunctional drug usage in later life, especially among young adults. Initially, the subject of childhood trauma is reviewed, with basic concepts and causes of the trauma. It is seen in the study that abusive relationships in childhood, from physical violence to sexual violence, can impose severe trauma on a child. Other causes can be dysfunctional families, in which either of the parents is violent, abusive or addicted. These instances can increase the chances of an individual becoming a functional or dysfunctional drug addict as they grow up.

Among the major factors for developing drug abuse patterns in young adults is the background of a dysfunctional family. Such habits can greatly impact the mental health of the person as well as the family or friends of that person. In such situations, it is found that there is a chance of repeating the cycle of the same dysfunctional family from parents to children. Furthermore, data and statistics are also analysed to understand the scope of the drug use problem among young adults. It is seen that instances of drug abuse are rising, and the causes range from abusive relationships to boredom.

Analysis and Discussion

This chapter has been written to add to the topic of childhood trauma and its effect on drug usage in young adult life. A thorough analysis has been done of available studies to explore different causes of childhood trauma and their probable effects. As Bengtsson (2016) noted, content analysis helps develop a multidimensional insight into the topic to understand it better. Therefore, the chapter has been designed so that research aims are met and research questions are answered. A discussion about the content and literature is added in the later part of the study, followed by a chapter summary.

Critical Investigation of the Prominence of Healthy Childhood for Better Adult Life

According to the study by Campbell, Walker and Egede (2016), multiple factors affect childhood experiences and shape a person’s adult life. A similar study on the subject identified that childhood influences are critical in improving the quality of life in later adulthood (Milteer, Ginsburg and Mulligan, 2012). On the other hand, Reuben et al. (2016) argue that not all aspects of childhood affect adult life, as most are forgotten until a person reaches their early 20s. Therefore, it is argued that certain selected instances determine a person’s attitude in later life.

Regarding factors affecting childhood experiences, Piotrowska et al. (2017) highlight the importance of children and parent relationships in determining the nature of a person’s upbringing. On the contrary, the research conducted by Moffitt (2013) pinpoints external factors like school bullies as critical in maintaining a healthy or unhealthy childhood. A similar study by Grohmann, Kouwenberg and Menkhoff (2015) suggests that environmental factors of finances and savings are foremost in regulating the experiences of infancy that affect life in adulthood. Among external aspects of upbringing, Sobkin et al. (2016) note that the socio-demographic characteristics of society are critical in shaping the mindset of children throughout their lifetime.

In the context of the nature of the effect, Kiesel, Piescher and Edleson (2016) believe that childhood experiences only determine the academic excellence of a person’s life. In contrast, another study on the same subject has concluded that matters of early childhood determine the physical health of the person in adulthood (Larkin, Felitti and Anda, 2014). According to this study, a person with a traumatic childhood is more prone to developing chronic illnesses than a person with a healthy childhood. To support this argument, the study of Kitta et al. (2016) has illustrated that the deterioration rate of physical health directly depends on the nature of childhood.

Cook et al. (2017) researched the same topic and concluded that instead of physical health, early childhood experiences shape a person's mental health in later life. Another article by McQueen et al. (2018) supported the view of childhood and mental health by arguing that a traumatic childhood often results in severe social anxiety in the person as an adult. A study also found that childhood experiences affect how an adult handles stress, with victims of childhood trauma being more prone to panic attacks even in non-stressful situations (Nurius et al., 2015). On the other hand, Merrick et al. (2017) believe that experiences in infancy can seriously alter the remainder of the person’s life by initiating mental disorders like depression and forcing the person to become suicidal.

Identifying and Accessing the Factors that Cause Childhood Trauma

The study of Szilagyi et al. (2016) has identified that the majority of the factors leading to childhood trauma are due to the nature, attitude and behaviour of parents towards children. To add to the discussion, the study of Hogan et al. (2018) has illustrated that trauma in childhood is divided into two groups: intentional and unintentional. Nevertheless, parents may have been subjected to past experiences that become hindrances in their care for their children. Among unintentional causes of childhood trauma, emotional neglect is the foremost reason for distress in upbringing (Krüger and Fletcher, 2017).

This neglect gives rise to further problems, as Tashjian et al. (2016) note that sexual abuse of children usually happens in families where at least one of the parents is negligent of the child’s wellbeing. While comparing people with traumatic and healthy childhoods, Wekerle et al. (2018) found that emotional mistreatment is the biggest reason for childhood neglect and trauma. Cecil et al. (2017) have further added that emotional abuse and neglect are the most significant causes of childhood trauma and the most destructive form of trauma received in childhood. This is attributed to the fact that children who receive emotional neglect are bound to repeat the same neglect on their children when they become parents.

In contrast, Van der Kolk (2017) has highlighted that intentional abuse or violent behaviour from parents is more problematic in causing trauma. The research of Izaguirre and Cater (2018) has pointed out the role of mishandling, bullying and aggressiveness in parents as three main factors of physical causes of trauma among children. At the same time, Oshri et al. (2017) believe that parents' emotional mistreatment and judgmental behaviour are critical regarding the reasons for childhood treatment. As Hartling and Lindner (2016) discussed, parents can be psychologically abusive by regularly projecting insults and humiliation on their children. However, Camilo, Garrido and Calheiros (2016) argue that unrealistic academic expectations and restricting children from socialising are more common forms of emotional abuse.

Besides physical and emotional abuse, sexual mistreatment and violence are other factors that lead to childhood trauma (Bentovim, 2018). Motta (2020) denotes that sexual misconduct against children predominantly occurs from close family members or friends. However, Moffitt (2013) believes that more cases of sexual abuse are registered where exposure in school is the primary cause of sexual misconduct among children. Furthermore, the study by Venta, Velez and Lau (2016) highlighted that children from dysfunctional families have a higher chance of being sexually assaulted, as their parents do not fully protect them.

Critically Evaluating the Influence of Childhood Trauma on Drug Use Among Young Adults

According to the study by Martin et al. (2014), a range of traumas experienced by an individual at a young age leads to drug use among young adults. A similar author elaborated on the influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse while indicating that bullying has been identified as a major trauma that influences young adults to use drugs (Martin et al. 2014). However, the research of Taplin et al. (2014) indicated that community violence, such as racist comments and hostile behaviour, affects young adults emotionally, which leads to drug use. However, the research of Quinn et al. (2016) contradicted the idea by indicating that young adults tend to become drug addicts due to experiencing intimate partner violence at a young age.

A similar author regarded that physical violence between parents causes childhood trauma to their children, due to which those children begin using drugs when becoming young adults (Quinn et al. 2016). Furthermore, Wu et al. (2010) research highlighted that traumatic grief, such as the death of a close family member, makes childhood traumatic, due to which the individual tends to use drugs when becoming a young adult. Similarly, the research of Svingen et al. (2016) identified that post-traumatic stress is caused by a close family member's death that persists until the individual becomes a young adult and begins using the drug to minimize the stress.

Additionally, the research of Wu et al. (2010) contemplated that childhood trauma is caused by physical abuse at a young age that influences young adults to use the drug. However, the study by Quinn et al. (2016) argued that emotional abuse, such as sensitive comments on being indifferent, makes childhood traumatic for individuals, due to which they become drug addicts later in life. Taplin et al. (2014) research highlighted that sexual abuse is among the factors that affect children traumatically and leads to drug use among young adults.

However, the study of Harley et al. (2010) indicated that the weak nurturing of a child during a young age creates childhood trauma for such individuals that leads to drug use among these individuals during the young adult stage. According to the study by Porche et al. (2011), weak bonding between the parents and a child due to several factors, such as the imprisonment of a parent, creates childhood trauma for such individuals that inclines them to use drugs when becoming young adults.

Some studies, such as Svingen et al. (2016) and Quinn et al. (2016), asserted that weak academic performance at a young age could also cause a young adult to use the drug. Whereas the dissertation of Porche et al. (2011) stated that parental illness restricts the adequate bonding between the parents and child, the individual is inclined toward drug use when becoming a young adult. Similarly, the studies of Martin et al. (2014) and Harley et al. (2010) illustrated that parental substance abuse and emotional negligence by parents make childhood traumatic, consequently motivating young adults to use the drug.

Assessing the Benefits of the Trauma-Informed Practice to Social Institutions

Despite the significant influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse, trauma-informed practices could still counter its negative impact. According to the research of Wilson, Fauci, and Goodman (2015), trauma-informed practices assist multiple social institutions in minimizing the effect of trauma among various groups of individuals. A similar author added that trauma-informed practices consist of four major stages: trauma-aware, trauma-sensitive, trauma-responsive, and trauma-informed. These stages reduce the insecurity among victims of some trauma (Wilson, Fauci, and Goodman, 2015). Knight's (2015) research highlighted that one of the major benefits of trauma-informed practices is they create a proactive approach to safety.

However, the study by Brown, Harris, and Fallot (2013) stated that trauma-informed practices allow social activists to create a trauma-free environment for their clients, staff, and families. Additionally, the study of Donisch, Bray, and Gewirtz (2016) asserted that trauma-informed practices benefit the individual by preventing the occurrence of re-traumatization. However, the study of Goodman et al. (2016) indicated that trauma-informed practices benefit social institutions by creating sustainable opportunities for empowering the victims of trauma.

At the same time, Morgan et al. (2015) research emphasized the social environment created by trauma-informed practices at social institutions that contribute to building a fruitful relationship between trauma victims. The study of Lucero and Bussey (2012) stated that one of the main benefits of trauma-informed practices is they minimize the symptoms of trauma among the victims. However, the study by Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis (2018) argued that trauma-informed practices reduce the severity of drug use among traumatic individuals.

On the contrary, the dissertation of Donisch, Bray, and Gewirtz (2016) considered diminishing mental health symptoms among affected victims as a major benefit of trauma-informed practices. Additionally, Brown, Harris, and Fallot's (2013) research highlighted that trauma-informed practices make the treatment of trauma cost-effective for multiple victims. Moreover, a similar author specified that trauma-informed practices promote resilience and strength within social institutions that assist them in minimizing the effect of trauma among the victims (Brown, Harris, and Fallot, 2013).

Discussion

The first objective of this research is to promote the use of trauma-informed practice in social work. In the studies of Levenson (2017), the literature indicated that approximately 64-94% of students in college experience some trauma that affects their adult life. Similarly, the studies of Morgan et al. (2015) from content analysis highlighted that a high number of traumatic cases among young adults requires the promotion of trauma-informed practices at social institutions that can contribute to bringing sustainability to the lives of young adults.

Furthermore, the study of Corrigan and Hull's (2018) literature emphasized the element of empathy among the staff of the social institution that improves the condition of victims of childhood trauma. However, the studies of Donisch, Bray, and Gewirtz (2016) and Quiros and Benavidez-Hatzis (2018) from content analysis found that trauma-informed practices allow social activists to create a trauma-free environment for their clients, staff, and family at social institutions that facilitates their social work of promoting the trauma-informed approach in the society.

The studies of Cicchetti and Banny (2014) and Chamberlayne and Smith (2019) asserted that traumatic individuals resist opening up about their traumatic experiences of childhood. Thus, using trauma-informed practices creates a comfortable environment in their surroundings and assists them in opening up. The research of Brown, Harris, and Fallot (2013) and Lucero and Bussey (2012) from content analysis illustrated that trauma-informed practices could be promoted when social work is entirely based on the resilience and strength of victims of childhood trauma.

The study's second objective is to thoroughly create a link between traumatic childhood and dysfunctional drug use in later adult life. The research of Izaguirre and Cater (2018) highlighted that traumatic childhood had been one of the major reasons for dysfunctional drug use among young adults in later adult life. Similar research identified that physical abuse, such as sexual abuse during childhood, creates trauma among individuals. These people get involved in using a dysfunctional drug to minimize pain (Izaguirre and Cater, 2018). In contrast, the study of Campbell, Walker, and Egede (2016) from content analysis asserted that emotional negligence by parents in childhood creates a substantial possibility of dysfunctional drug use in later adult life due to childhood trauma.

The study by Cutuli, Alderfer, and Marsac (2019) literature stated the factors that make childhood traumatic, which were abuse, neglect, and violence. These studies focused on the influence of childhood trauma on drug abuse. The author further described that parental substance abuse highly affects a child's mental health during childhood, due to which they get highly inclined towards dysfunctional drug use in later adult life (Cutuli, Alderfer, and Marsac, 2019). However, the study of Piotrowska et al. (2017) from content analysis emphasized that physical violence, such as bullying at schools and other surroundings during childhood, is a significant determinant that causes dysfunctional drug use among young adults in later adult life.

The third objective of the study is to highlight the family support outside the home that provides the opportunity to be resilient and overcome exposure to trauma and abuse. The studies of Karson and Sparks (2013) indicated that children tend to visit several social groups of traumatic people where discussion related to their trauma and abuse occurs. A similar author elaborated that these groups respect every individual's pain and provide moral support to overcome the trauma. However, the studies of Martin et al. (2014) and Harley et al. (2010) from content analysis focused on social institutions that promote trauma-informed practice among the victims of trauma so that they can overcome the issue and lead a sustainable life.

Furthermore, the research of Crews et al. (2017) emphasised support from close relatives such as uncles, aunts, and grandparents about trauma and abuse faced by children at a young age who take responsibility for nurturing the children by themselves to minimize the exposure to trauma and abuse. The study of Quinn et al. (2016) in content analysis contemplated that teachers in educational institutions play a dominant role in minimizing the exposure of young children to trauma and abuse as they make sure to be vigilant in identifying the issues related to trauma and abuse among young adults.

The final objective of the study is to highlight the importance of a healthy childhood for better later adult life. The survey by Surveyer Ginsburg and Mulligan (2012) specified that a healthy childhood assists an individual in achieving their lifetime goals in later adult life. Similarly, Grohmann, Kouwenberg, and Menkhoff's (2015) study from the content analysis indicated that young adults with healthier childhood are more focused on fulfilling their dreams. Additionally, from the studies of Iwamoto and Smiler (2013) and Larkin, Felitti, and Anda (2014), it has been found that individuals with healthier childhoods tend to have greater life expectancy during their adult life than people with traumatic childhoods.

However, the studies of Kiesel, Piescher, and Edleson (2016) from content analysis stated that people with healthier childhood have greater self-esteem that assists them in leading prosperous life in later adulthood. Furthermore, the studies of Morrall, Worton, and Antony (2020) and Williams (2019) asserted that healthy childhood significantly minimizes the probability of developing a mental disorder in adult age. However, the research of McQueen et al. (2018) from content analysis found that socio-demographic aspects of society create a healthier childhood, which leads to an individual leading a better adult life.

Chapter Summary

The current chapter discussed the analysis of the study by employing the content analysis technique in which multiple secondary sources such as journals, articles, books, and magazines are used to compare and contrast distinct ideas related to the topic. By critically examining the content, it has been found that trauma-informed practices play a prominent in improving the quality of social work performed by social institutions to eradicate the symptoms and issues of childhood trauma. Additionally, it has been evaluated that children get moral support from close relatives, teachers, and friends to minimize their exposure to trauma and abuse. Moreover, the studies found that physical, mental, and emotional abuse in early childhood plays a prominent role in promoting dysfunctional drug use in later adult life. Lastly, the findings indicated that a healthier childhood assists individuals in achieving life goals and leading sustainable adult lives in the future.

Review the following:

Download PDF File

Download PDF File

REFERENCES

Acheson, A., Richard, D.M., Mathias, C.W. and Dougherty, D.M., 2011. Adults with a family history of alcohol-related problems are more impulsive on measures of response initiation and response inhibition. Drug and alcohol dependence, 117(2-3), pp.198-203.

Akbey, Z.Y., Yildiz, M. and Gündüz, N., 2019. Is There Any Association Between Childhood Traumatic Experiences, Dissociation, and Psychotic Symptoms in Schizophrenic Patients? Psychiatry Investigation, 16(5), p.346.

Aldridge, J., Measham, F. and Williams, L., 2013. Illegal leisure revisited: Changing patterns of alcohol and drug use in adolescents and young adults. Routledge.

Allbaugh, L.J., Mack, S.A., Culmone, H.D., Hosey, A.M., Dunn, S.E. and Kaslow, N.J., 2018. Relational factors are critical in the link between childhood emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. Psychological Services, 15(3), p.298.

Askew, R., 2016. Functional fun: Legitimizing adult recreational drug use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 36, pp.112-119.

Bachman, J.G., Wadsworth, K.N., O'Malley, P.M., Johnston, L.D. and Schulenberg, J.E., 2013. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Psychology Press.

Banitt, S.P., 2018. Wisdom, Attachment, and Love in Trauma Therapy: Beyond Evidence-Based Practice. Routledge.

BBC News, 2020. The Drugs Being Used At UK Festivals. [online] BBC News. Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-44482290> [Accessed 27 March 2020].

BBC News. 2019. Class A Drug Use 'At Record Levels'. [Online] Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-49766047> [Accessed 27 March 2020].

Bengtsson, M., 2016. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, pp.8-14.

Bentovim, A., 2018. Trauma-organized systems: Physical and sexual abuse in families. Routledge.

Berger, R., Quiros, L. and Benavidez-Hatzis, J.R., 2018. The intersection of identities in supervision for trauma-informed practice: Challenges and strategies. The Clinical Supervisor, 37(1), pp.122-141.

Brockie, T.N., Dana-Sacco, G., Wallen, G.R., Wilcox, H.C. and Campbell, J.C., 2015. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use, and suicide attempt in reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3-4), pp.411-421.

Brown, S.M. and Shillington, A.M., 2017. Childhood adversity and the risk of substance use and delinquency: The role of protective adult relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, pp.211-221.

Brown, V.B., Harris, M., and Fallot, R., 2013. Moving toward trauma-informed practice in addiction treatment: A collaborative model of agency assessment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(5), pp.386-393.

Bryant‐Davis, T., Adams, T., Alejandre, A., and Gray, A.A., 2017. The trauma lens of police violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), pp.852-871.

Camilo, C., Garrido, M.V. and Calheiros, M.M., 2016. Implicit measures of child abuse and neglect: A systematic review. Aggression and violent behavior, 29, pp.43-54.

Campbell, J.A., Walker, R.J. and Egede, L.E., 2016. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviours, and morbidity in adulthood. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(3), pp.344-352.

Carpenter, C.S., McClellan, C.B. and Rees, D.I., 2017. Economic conditions, illicit drug use, and substance use disorders in the United States. Journal of Health Economics, 52, pp.63-73.

Cecil, C.A., Viding, E., Fearon, P., Glaser, D. and McCrory, E.J., 2017. Disentangling the mental health impact of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, pp.106-119.

Chamberlayne, P. and Smith, M. eds., 2019. Art, Creativity, and Imagination in Social Work Practices. Routledge.

Chung, M.C., Shakra, M., AlQarni, N., AlMazrouei, M., Al Mazrouei, S. and Al Hashimi, S., 2018. Posttraumatic stress among Syrian refugees: trauma exposure characteristics, trauma centrality, and emotional suppression. Psychiatry, 81(1), pp.54-70.

Clarke, R.J., Clarke, E.A., Roe-Sepowitz, D., and Fey, R., 2012. Age at entry into prostitution: Relationship to drug use, race, suicide, education level, childhood abuse, and family experiences. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(3), pp.270-289.

Cohen, D., 2017. How the child's mind develops. Routledge.

Cohen, J.A., Deblinger, E. and Mannarino, A.P., 2018. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and families. Psychotherapy Research, 28(1), pp.47-57.

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., DeRosa, R., Hubbard, R., Kagan, R., Liautaud, J. and Mallah, K., 2017. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), pp.390-398.

Cormack, C. and Carr, A., 2013. 7 Drug abuse. What Works with Children and Adolescents?: A Critical Review of Psychological Interventions with Children, Adolescents and their Families, p.155.

Corrigan, F. and Hull, A.M., 2018. The emerging psychological trauma paradigm: An overview of the challenge to current models of mental disorder and their treatment. International Journal of Cognitive Analytic Therapy and Relational Mental Health, 2, pp.121-146.

Cotto, J.H., Davis, E., Dowling, G.J., Elcano, J.C., Staton, A.B. and Weiss, S.R., 2010. Gender effects on drug use, abuse, and dependence: a special analysis of results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Gender medicine, 7(5), pp.402-413.

Craig, J.M., Piquero, A.R., Farrington, D.P. and Ttofi, M.M., 2017. A little early risk goes a long bad way: Adverse childhood experiences and life-course offending in the Cambridge study. Journal of Criminal Justice, 53, pp.34-45.

Crews, F.T., Walter, T.J., Coleman, L.G. and Vetrano, R.P., 2017. Toll-like receptor signalling and stages of addiction. Psychopharmacology, 234(9-10), pp.1483-1498.

Cervenka, A., 2016. Neurobiological phenotypes are associated with a family history of alcoholism. Drug and alcohol dependence, 158, pp.8-21.

Cutuli, J.J., Alderfer, M.A. and Marsac, M.L., 2019. Introduction to the special issue: Trauma-informed care for children and families. Psychological Services, 16(1), p.1.

Davenport, S. and Pardo, B., 2016. The Dangerous Drugs Act amendment in Jamaica: Reviewing goals, implementation, and challenges. International Journal of Drug Policy, 37, pp.60-69.

Degenhardt, L., Peacock, A., Colledge, S., Leung, J., Grebely, J., Vickerman, P., Stone, J., Cunningham, E.B., Trickey, A., Dumchev, K. and Lynskey, M., 2017. The global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 5(12), pp.e1192-e1207.

Donisch, K., Bray, C. and Gewirtz, A., 2016. Child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health, and education providers’ conceptualizations of trauma-informed practice. Child maltreatment, 21(2), pp.125-134.

Duffell, N. and Basset, T., 2016. Trauma, Abandonment, and Privilege: A guide to therapeutic work with boarding school survivors. Routledge.

Epstein, C., Hahn, H., Berkowitz, S. and Marans, S., 2017. The child and family traumatic stress intervention. In Evidence-Based Treatments for Trauma-Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents (pp. 145-166). Springer, Cham.

Erickson, C.K., 2018. The science of addiction: From neurobiology to treatment. WW Norton & Company.

Garner, A.S., Shonkoff, J.P., Siegel, B.S., Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., Wood, D.L., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, 2012. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the paediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics, 129(1), pp.e224-e231.

Goodman, L.A., Sullivan, C.M., Serrata, J., Perilla, J., Wilson, J.M., Fauci, J.E. and DiGiovanni, C.D., 2016. development and validation of the trauma‐informed practice scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(6), pp.747-764.

Gov.UK, 2020. Welcome To GOV.UK. [online] Gov.UK. Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/> [Accessed 27 March 2020].

Grecu, A.M., Dave, D.M. and Saffer, H., 2019. Mandatory access to prescription drug monitoring programs and prescription drug abuse. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 38(1), pp.181-209.

Griffin, K.W., Lowe, S.R., Botvin, C. and Acevedo, B.P., 2019. Patterns of adolescent tobacco and alcohol use as predictors of illicit and prescription drug abuse in minority young adults. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community, 47(3), pp.228-242.

Grohmann, A., Kouwenberg, R. and Menkhoff, L., 2015. Childhood roots of financial literacy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 51, pp.114-133.

Haas, L., 2018. Trauma-Informed Practice: The Impact of Professional Development on School Staff. The University of St. Francis.

Hanson, K.L., Medina, K.L., Padula, C.B., Tapert, S.F. and Brown, S.A., 2011. Impact of adolescent alcohol and drug use on neuropsychological functioning in young adulthood: 10-year outcomes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 20(2), pp.135-154.

Harley, M., Kelleher, I., Clarke, M., Lynch, F., Arseneault, L., Connor, D., Fitzpatrick, C., and Cannon, M., 2010. Cannabis use and childhood trauma interact additively to increase the risk of psychotic symptoms in adolescence. Psychological medicine, 40(10), pp.1627-1634.

Hartling, L.M. and Lindner, E.G., 2016. Healing humiliation: From reaction to creative action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), pp.383-390.

Higgins, D.J., Kaufman, K., and Erooga, M., 2016. How can child welfare and youth-serving organizations keep children safe? Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, (44), p.48.

Hobkirk, A.L., Bell, R.P., Utevsky, A.V., Huettel, S., and Meade, C.S., 2019. Reward and executive control network resting-state functional connectivity is associated with impulsivity during reward-based decision-making for cocaine users. Drug and alcohol dependence, 194, pp.32-39.

Hogan, C.M., Weaver, N.L., Cioni, C., Fry, J., Hamilton, A., and Thompson, S., 2018. Parental perceptions, risks, and incidence of pediatric unintentional injuries. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 44(3), pp.267-273.

Husky, J.L., 2010. Are adolescents with a high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 5(1), p.19.

Iwamoto, D.K. and Smiler, A.P., 2013. Alcohol makes you macho and helps you make friends: The role of masculine norms and peer pressure in adolescent boys’ and girls’ alcohol use. Substance use & misuse, 48(5), pp.371-378.

Izaguirre, A. and Cater, Å., 2018. Child witnesses to intimate partner violence: Their descriptions of talking to people about the violence. Journal of interpersonal violence, 33(24), pp.3711-3731.

Karson, M. and Sparks, E., 2013. Patterns of child abuse: How dysfunctional transactions are replicated in individuals, families, and the child welfare system. Routledge.

Kiesel, L.R., Piescher, K.N. and Edleson, J.L., 2016. The relationship between child maltreatment, intimate partner violence exposure, and academic performance. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(4), pp.434-456.

Kim, S.J., Marsch, L.A., Hancock, J.T. and Das, A.K., 2017. Scaling up research on drug abuse and addiction through social media big data. Journal of medical Internet research, 19(10), p.e353.

Kirsch, D., Nemeroff, C.M. and Lippard, E.T., 2020. Early life stress and substance use disorders: underlying neurobiology and pathways to adverse outcomes. Adversity and Resilience Science, pp.1-19.

Kitta, M., Gouva, M., Hadjigeorgiou, G., George, K. and Bonotis, K., 2016. Childhood Trauma and Adult Distress Symptoms. J Trauma Stress Disor Treat 5, 3, p.2.

Knight, C., 2015. Trauma-informed social work practice: Practice considerations and challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(1), pp.25-37.

Kong, G., Morean, M.E., Cavallo, D.A., Camenga, D.R. and Krishnan-Sarin, S., 2015. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine & tobacco research, 17(7), pp.847-854.

Krüger, C. and Fletcher, L., 2017. Predicting a dissociative disorder from the type of childhood maltreatment and abuser–abused relational tie. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 18(3), pp.356-372.

Larkin, H., Felitti, V.J. and Anda, R.F., 2014. Social work and adverse childhood experiences research: Implications for practice and health policy. Social work in public health, 29(1), pp.1-16.

Llabre, M.M., Schneiderman, N., Gallo, L.C., Arguelles, W., Daviglus, M.L. and Gonzalez, F., 2017. Childhood trauma and adult risk factors and disease in Hispanics/Latinos in the US: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychosomatic medicine, 79(2), p.172.

Lucero, N.M. and Bussey, M., 2012. A collaborative and trauma-informed practice model for urban Indian child welfare. Child Welfare, 91(3), p.89.

Mandavia, A., Robinson, G.G., Bradley, B., Ressler, K.J., and Powers, A., 2016. Exposure to childhood abuse and later substance use: Indirect effects of emotion dysregulation and exposure to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29(5), pp.422-429.

Marshall, M., Shannon, C., Meenagh, C., Mc Corry, N., and Mulholland, C., 2018. The association between childhood trauma, parental bonding, depressive symptoms, and interpersonal functioning in depression and bipolar disorder. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 35(1), pp.23-32.

Martin, L., Viljoen, M., Kidd, M. and Seedat, S., 2014. Are childhood trauma exposures predictive of anxiety sensitivity in school-attending youth? Journal of Affective Disorders, 168, pp.5-12.

Mayo Clinic. 2017. Drug Addiction (Substance Use Disorder) - Symptoms And Causes. [online] Available at: <https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/drug-addiction/symptoms-causes/syc-20365112> [Accessed 27 March 2020].

McElvaney, R. and Tatlow-Golden, M., 2016. A traumatized and traumatizing system: Professionals' experiences in meeting the mental health needs of young people in the care and youth justice systems in Ireland. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, pp.62-69.

McQueen, D., Itzin, C., Kennedy, R., Sinason, V., and Maxted, F. eds., 2018. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy after child abuse: The treatment of adults and children who have experienced sexual abuse, violence, and neglect in childhood. Routledge.

Mergler, M., Driessen, M., Havemann-Reinecke, U., Wedekind, D., Lüdecke, C., Ohlmeier, M., Chodzinski, C., Teunißen, S., Weirich, S., Kemper, U. and Renner, W., 2018. Differential relationships of PTSD and childhood trauma with the course of substance use disorders. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 93, pp.57-63.

Merrick, M.T., Ports, K.A., Ford, D.C., Afifi, T.O., Gershoff, E.T. and Grogan-Kaylor, A., 2017. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child abuse & neglect, 69, pp.10-19.

Miller, S., 2019. What Doesn't Kill You Still Hurts Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Modern Young Adult Literature.

Milteer, R.M., Ginsburg, K.R. and Mulligan, D.A., 2012. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining a strong parent-child bond: Focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics, 129(1), pp.e204-e213.

Moffitt, T.E., 2013. Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), pp.1619-1634.

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M. and Han, B., 2016. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6), p.e20161878.

Morgan, A., Pendergast, D., Brown, R. and Heck, D., 2015. Relational ways of being an educator: Trauma-informed practice supporting disenfranchised young people. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(10), pp.1037-1051.

Morrall, P., Worton, K. and Antony, D., 2020. Why is murder fascinating, and why does it matter to mental health professionals? Mental Health Practice, 23(1).

Motta, R., 2020. Secondary trauma in children and school personnel. In Addressing Multicultural Needs in School Guidance and Counseling (pp. 65-81). IGI Global.

Müller, C.P., 2018. Animal models of psychoactive drug use and addiction–present problems and future needs for translational approaches. Behavioral brain research, 352, pp.109-115.

Neelakantan, L., Hetrick, S. and Michelson, D., 2018. Users’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. European child & adolescent psychiatry, pp.1-21.

Nurius, P.S., Green, S., Logan-Greene, P. and Borja, S., 2015. Life-course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis. Child abuse & neglect, 45, pp.143-153.

Ogden, T. and Hagen, K.A., 2018. Adolescent mental health: Prevention and intervention. Routledge.

Oliver, B. and Abel, N., 2017. Special populations of children and adolescents who have significant needs. Counselling children and adolescents: Working in school and clinical mental health settings, pp.371-407.

Oshri, A., Carlson, M.W., Kwon, J.A., Zeichner, A. and Wickrama, K.K., 2017. Developmental growth trajectories of self-esteem in adolescence: associations with child neglect and drug use and abuse in young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(1), pp.151-164.

Petrova, H.A., Zavarzina, O.O., Kytianova, I.P. and Kozyakov, R.V., 2015. Social and personal factors of stable remission for people with drug addictions. Psychology in Russia, 8(4), p.126.

Pilatti, A., Caneto, F., Garimaldi, J.A., Vera, B.D.V. and Pautassi, R.M., 2014. Contribution of time of drinking onset and family history of alcohol problems in alcohol and drug use behaviours in Argentinean college students. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 49(2), pp.128-137.

Piotrowska, P.J., Tully, L.A., Lenroot, R., Kimonis, E., Hawes, D., Moul, C., Frick, P.J., Anderson, V., and Dadds, M.R., 2017. Mothers, fathers, and parental systems: A conceptual model of parental engagement in programs for child mental health—Connect, Attend, Participate, Enact (CAPE). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(2), pp.146-161.

Platt, L., Minozzi, S., Reed, J., Vickerman, P., Hagan, H., French, C., Jordan, A., Degenhardt, L., Hope, V., Hutchinson, S., and Maher, L., 2017. Needle syringe programs and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9).

Porche, M.V., Fortuna, L.R., Lin, J. and Alegria, M., 2011. Childhood trauma and psychiatric disorders as correlates of school dropout in a national sample of young adults. Child Development, 82(3), pp.982-998.

Pourallahvirdi, M., Rahmani, F., Ranjbar, F., Ebrahimi Bakhtavar, H. and Ettehadi, A., 2016. Major causes of drug abuse from the viewpoint of addicted persons referred to addiction treatment centres in Tabriz city, Iran. Archives of Neuroscience, 3(3).

Powers, A., Fani, N., Cross, D., Ressler, K.J. and Bradley, B., 2016. Childhood trauma, PTSD, and psychosis: findings from a highly traumatized, minority sample. Child abuse & neglect, 58, pp.111-118.

Quinn, K., Boone, L., Scheidell, J.D., Mateu-Gelabert, P., McGorray, S.P., Beharie, N., Cottler, L.B. and Khan, M.R., 2016. The relationships between childhood trauma and adulthood prescription pain reliever misuse and injection drug use. Drug and alcohol dependence, 169, pp.190-198.

Ramo, D.E., Grov, C., Delucchi, K., Kelly, B.C. and Parsons, J.T., 2010. Typology of club drug use among young adults recruited using time-space sampling. Drug and alcohol dependence, 107(2-3), pp.119-127.

Redonnet, B., Chollet, A., Fombonne, E., Bowes, L. and Melchior, M., 2012. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drug use among young adults: the socioeconomic context. Drug and alcohol dependence, 121(3), pp.231-239.

Reuben, A., Moffitt, T.E., Caspi, A., Belsky, D.W., Harrington, H., Schroeder, F., Hogan, S., Ramrakha, S., Poulton, R., and Danese, A., 2016. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences to predict adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(10), pp.1103-1112.

Richardson, G.A., Larkby, C., Goldschmidt, L. and Day, N.L., 2013. Adolescent initiation of drug use: effects of prenatal cocaine exposure. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(1), pp.37-46.

Rosen, A.L., Handley, E.D., Cicchetti, D. and Rogosch, F.A., 2018. The impact of patterns of trauma exposure among low-income children with and without histories of child maltreatment. Child abuse & neglect, 80, pp.301-311.

Runyon, M.K., Risch, E. and Deblinger, E., 2019. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy: An evidence-based approach for helping children overcome the impact of child abuse and trauma.

Sobkin, V.S., Veraksa, A.N., Yakupova, V.A., Bukhalenkova, D.A., Fedotova, A.V. and Khalutina, U.A., 2016. The connection of socio-demographic factors and child-parent relationships to the psychological aspects of children's development. Psychology in Russia, 9(4), p.59.

Svingen, L., Dykstra, R.E., Simpson, J.L., Jaffe, A.E., Bevins, R.A., Carlo, G., DiLillo, D. and Grant, K.M., 2016. Associations between family history of substance use, childhood trauma, and age of first drug use in persons with methamphetamine dependence. Journal of addiction medicine, 10(4), pp.269-273.

Szilagyi, M., Kerker, B.D., Storfer-Isser, A., Stein, R.E., Garner, A., O'Connor, K.G., Hoagwood, K.E. and Horwitz, S.M., 2016. Factors associated with whether paediatricians inquire about parents' adverse childhood experiences. Academic paediatrics, 16(7), pp.668-675.

Tang, Y.Y., Tang, R. and Posner, M.I., 2016. Mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation and reduces drug abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, pp.S13-S18.

Taplin, C., Saddichha, S., Li, K. and Krausz, M.R., 2014. Family history of alcohol and drug abuse, childhood trauma, and age of first drug injection. Substance use & misuse, 49(10), pp.1311-1316.

Tashjian, S.M., Goldfarb, D., Goodman, G.S., Quas, J.A. and Edelstein, R., 2016. Delay in disclosure of non-parental child sexual abuse in the context of emotional and physical maltreatment: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 58, pp.149-159.

Teese, R., 2018. Reckless Behaviour in Emerging Adulthood: A Psychosocial Approach.

Thompson, E., and Kaufman, J., 2019. Prevention, Intervention, and Policy Strategies to Reduce the Individual and Societal Costs Associated with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) for Children in Baltimore City.

Turner, H.A., Mitchell, K.J., Jones, L., and Shattuck, A., 2017. Assessing the impact of peer harassment: Incident characteristics and outcomes in a national sample of youth. Journal of school violence, 16(1), pp.1-24.

Valles, N.L., Harris, T.B. and Sargent, J., 2019. Mental Health Issues: Child Physical Abuse, Neglect, and Emotional Abuse. In A Practical Guide to the Evaluation of Child Physical Abuse and Neglect (pp. 517-543). Springer, Cham.

Van der Kolk, B.A., 2017. Developmental trauma disorder: toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), pp.401-408.

Venta, A., Velez, L. and Lau, J., 2016. The role of parental depressive symptoms in predicting dysfunctional discipline among parents at high risk for child maltreatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), pp.3076-3082.

Verdejo-Garcia, A., Chong, T.T.J., Stout, J.C., Yücel, M. and London, E.D., 2018. Stages of dysfunctional decision-making in addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 164, pp.99-105.

Vergara, V.M., Weiland, B.J., Hutchison, K.E. and Calhoun, V.D., 2018. The impact of combinations of alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis on dynamic brain connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(4), pp.877-890.

Vogt, R., 2019. The Traumatized Memory–Protection and Resistance: How traumatic stress encrypts itself in the body, behaviour, and soul and how to detect it. Lehmanns Media.

Wang, C.Y., Zhang, K. and Zhang, M., 2017. Dysfunctional attitudes, learned helplessness, and coping styles among men with substance use disorders. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 45(2), pp.269-280.

Wekerle, C., Wolfe, D.A., Cohen, J.A., Bromberg, D.S. and Murray, L., 2018. Childhood maltreatment (Vol. 4). Hogrefe Publishing.

Wilens, T.E., Martelon, M., Joshi, G., Bateman, C., Fried, R., Petty, C. and Biederman, J., 2011. Does ADHD predict substance-use disorders? A 10-year follow-up study of young adults with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(6), pp.543-553.