Analyzing Factors Responsible for Leadership Gap in Healthcare System: Suggesting Viable Solutions

December 21, 2020

Improving Occupants Safety in High Rise Buildings: Everything You Need to Know About Fire Safety

December 21, 2020

Patient Satisfaction among adult cancer patients in oncology wards in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)

1.1 Introduction

In the current study, patient satisfaction is examined as an aspect of patient experience and as an indicator of the quality of care among adult cancer patients in oncology wards in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The aim of the current sequential mixed-methods study is to assess patient satisfaction (a characteristic of patient experience) primarily as an indicator of the quality of care among adult cancer patients in oncology wards at the Saudi Regional Cancer Centre in Riyadh (SRCC), in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. To do this, an MMR was used, including both formal quantitative research instruments (questionnaires) and qualitative, one-to-one interviews with patients.

Patient satisfaction is widely accepted to be an important aspect of the patient experience (Cleary et al.1989; Fitzpatrick 1991; Carr-Hill 1992; Stizia and Wood 1997; Stewart 2001; Copnell et al.2009). Patient satisfaction has always been a priority issue for health care authorities in the Saudi region evident from the recent initiative taken by the Saudi health setup to achieve “Joint Commission International (JCI)” accreditation which has further increased the importance of patient satisfaction (Alturki and Khan 2013). Patient satisfaction has been attributed to a range of factors, in particular interpersonal and structural factors (Donabedian 1980).

A core part of patient satisfaction relates to the quality of care provided by the healthcare provider (Donabedian 1980). Quality of care can be defined as access to necessary, effective health structures and service processes. Patient satisfaction with the quality of care correlates, in turn, with clinical effectiveness. That is, patient satisfaction largely depends on the confluence of healthcare providers’ practices, skills and competence, in specific contexts of time and location. The objective of these practices is to improve the patient experience to provide satisfaction through improving the quality of care to attain positive outcomes from healthcare delivery. Interpersonal factors that can have a significant influence on patient satisfaction include the nurses’ and doctors’ communication with patients, whilst significant structural factors include the size of the hospital and ward (Donabedian 1980).

Despite the acknowledged importance of patient satisfaction to patient experience, it is difficult to isolate and measure. Studies such as those by Hobb (2009) and Jagosh et al. (2011) indicate that there is no one-size-fits-all concept of patient satisfaction, due to its relativity and localisation.

The issue of quality of care has been developed as part of the recent emphasis on the systematic assessment of health care services performance across the globe (Groene et al, 2008). A key goal of improvement initiatives is to enhance patients’ experiences of health services. Derived from this concept is an aspect of patient experience; patient satisfaction which is of particular interest to the current study, specifically satisfaction attained by patients for the quality of care they receive.

Although researchers disagree on which indicators of healthcare quality are most valid, the most frequently cited dimensions of quality of care include safety, effectiveness, equity, efficiency, timeliness, and patient-centredness (IOM 2001; Doyle et al.2013 Beattie et al. 2014). The last of these, patient-centredness, has developed as a particularly fruitful area of inquiry, with researchers discovering that the doctor-patient relationship can be therapeutic (Krupat et al. 2001; Street et al. 2009; Kenny et al. 2010), and that patients’ religious/spiritual needs should be integrated into their treatment (Williamson and Harrisons 2010). However, it must be noted that on the other hand, patient-centredness does not necessarily guarantee patient satisfaction (Kupfer and Bond 2012).

In the context of the KSA, the measurement of healthcare quality in general and of patient satisfaction, in particular, is even more complicated than in Western nations. This is because the models for assessing healthcare were developed in and for Western healthcare systems (particularly in Europe and North America) and they do not translate neatly to the KSA. However, the KSA’s healthcare system is at present growing increasingly Westernized, although the residue of the old system persists—including a subordinate role for women, language barriers between providers and patients, and the practice of limiting information disclosure to patients (Younge et al 1997; Al-Shahri 2002). The main areas of the Westernization of the KSA healthcare system include health policy, standards of care, and the education of healthcare providers. In addition, KSA hospitals are seeking accreditation from major international bodies. The World Health Organization is targeting health improvement in the KSA, and the health sector is collaborating with international bodies such as international research centres and the academic sector (WHO 2009; Al-Khenizan and Shaw 2011; Al-Malki 2011). Thus, to a significant extent in this new environment, it is now possible to explore the measures of patient satisfaction that were derived in the West in the context of the KSA. Indeed, there are certain features of the KSA’s healthcare system that make this issue both urgent and complex, since they can significantly impact the quality of care. Three key features are gender politics, non-disclosure practices, and language barriers between providers and patients.

1.2 Aims of the study and research questions

The aim of this sequential mixed-methods study was to assess patient satisfaction; an aspect of patient experience, primarily as an indicator of the quality of care among adult cancer patients in oncology wards at the Saudi Regional Cancer Centre in Riyadh (SRCC), in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Throughout the current study, clinical effectiveness is emphasised to comprehend the patient experience of their healthcare within oncology wards in SRCC.

The main research question emergent from this primary aim was to explore: What factors contribute to or hinder patient satisfaction with care in the oncology wards setting in the SRCC?

The specific aims of the research were as follows:

- To determine the likelihood that clinical effectiveness is associated with patient satisfaction in adult oncology ward settings in SRCC.

- To determine how likely the accessibility to health care is associated with patient satisfaction in adult oncology ward settings in SRCC.

- To describe the characteristics of patients in adult oncology ward settings in SRCC.

- To explore the extent to which interpersonal aspects of care influence patient satisfaction in adult oncology ward settings in SRCC.

- To provide recommendations for enhancing patient satisfaction in oncology ward settings in KSA.

- To discuss the extent to which and in what ways the qualitative findings help to explain the initial quantitative results of patient satisfaction in oncology settings in KSA.

The specific sub-questions formulated to achieve the specific aims of the study are as follows:

- Does the clinical effectiveness of health care (doctors’ and nurses’ skills, information provision, availability) influence adult oncology inpatients’ satisfaction with care at the SRCC in Riyadh?

- Does accessibility to health care (service organisation) influence adult oncology inpatients’ satisfaction with care at the SRCC in Riyadh?

- What are the socio-demographic characteristics of adult oncology inpatients at the SRCC in Riyadh?

- How do interpersonal aspects of care influence adult oncology inpatients’ satisfaction with care at the SRCC in Riyadh?

- How do socio-cultural communication factors influence adult oncology inpatients’ satisfaction with care at the SRCC in Riyadh?

1.3 The significance of the research

This research is significant in the following ways:

(a) The current study is one of the first in the context of the KSA to use a patient experience within a hospital context to investigate patient satisfaction;

(b) Outside a Western context (Western Europe and North America) there has been little research conducted internationally on patient satisfaction using the mixed methods approach (Merkouris et al. 2004); Hyrkas 2003).

(c) By illuminating the doctor-patient and nurse-patient relationship in the KSA, the current study contributes to the understanding of how these relationships operate in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC); which includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, and other Arab countries (in relation to religious beliefs, cultural beliefs and patriarchal culture).

The current study will be able to influence future practices, education, and research on patient satisfaction and experiences that are held with healthcare providers in oncology wards throughout the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

1.4 Patient satisfaction and quality of :

This section clarifies how key terms were defined using a combination of Donabedian 1980 and Quality Dimensions 6 aims OF IOM as the prime source of definitions to quality, including quality of care, clinical effectiveness, patient experience, and patient satisfaction

1.4.1 Quality of care

Quality of care is a multi-dimensional concept that can be studied from a number of different perspectives (Chassin and Gavin 1998; Heath et al. 2009). For the current study, quality of care is defined and analysed using a combination of the Donabedian model (1980) and the Institute of Medicines Six dimensions of care. Campbell et al. (2000, p. 1614) define the quality of care as ‘whether individuals can access the health structures and processes of care which they need and whether the care received is effective’, whilst for Lohr (1990) it is ‘the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge (Lohr 1990, p.65).

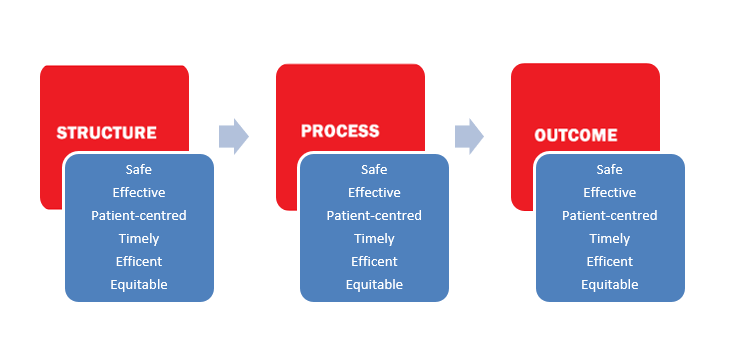

Quality of care can be divided into different dimensions according to the aspects of care being assessed. Donabedian’s (1980) seminal framework for defining quality of care in healthcare settings has three components: structure, process, and outcomes. Structural components include the context in which care is delivered (including facilities, equipment, and organizational characteristics). Process components include all the actions that makeup healthcare (such as diagnosis and treatment). And outcome components include all the effects of healthcare on patients or populations. The Donabedian care-assessment model has been widely used in international healthcare settings to assess patient satisfaction with the quality of care (Ware et al.1989; Campbell et al. 2000; Kringos et al. 2010; Khamis and Njau 2014). The model is an important component of the current study’s framework.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2001) devise six dimensions of health care quality known categorically as; safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient, and equitable. Based on these dimensions, safe includes avoiding harm to patients from the care that is proposed to help them; effective include the provision of services that has their foundation in scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and restrain from providing services to those not likely to benefit which means avoiding the underuse and misuse of resources; patient-centred means providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and making sure that patients’ values are the ones guiding all the clinical decisions made; timely means the reduction of wait and often harmful delays for both those who receive and give care; efficient is avoiding waste of resources such as equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy; lastly, equitable is providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, location, and socio-economic status.

Based on the analysis of both forms of measuring the quality of care the Donabedian’s model (1980) and IOM’s (2001) dimensions of care can be combined to measure and assess the quality of care more efficiently. Each of the Donabedian’s categories of structure, process and outcome can be subdivided to include the six dimensions of quality to ensure that each of the stages was executed effectively to derive inferences about the quality of care in the oncology ward setting in KSA in the current study.

Figure 1- Combination of Donabedian' Model of care and IOM's 6 dimensions of care

1.4.2 Clinical effectiveness

The construct of clinical effectiveness is closely related to the quality of care and patient experience but refers specifically to the efficacy of care delivered by practitioners. Clinical effectiveness can be defined as ‘the right person doing the right thing (evidence-based practice) in the right way (skills and competence) at the right time (providing treatment and service when a patient needs them), in the right place (location of treatment and service) with the right result (clinical effectiveness/health gain’ (NHS QIS 2005). Methods for measuring and assessing clinical effectiveness are discussed further in Chapter 2. The evidence found in the literature suggests that there is a positive association between patient experience and clinical effectiveness (Doyle et al. 2013). In the context of the KSA, there is a lack of evidence of assessment of patient experience including satisfaction from the clinical effectiveness perspective.

1.4.3 Patient experience and patient satisfaction

Currently, patient experience is recognized as one of the crucial pillars of quality of care (Tsianakas et al.2012; Beattie et al. 2015) which is generally defined as the patient’s experience of the healthcare process impacted by the extent and assurance of quality developed through clinical effectiveness. One aspect of patient experience is the construct at the heart of the current study specifically, patient satisfaction. In general, patient satisfaction is defined as a health care recipient’s reaction to salient aspects of context, process and results of their service experience’ (Pascoe 1983 p.186). Patient satisfaction is inextricably linked to the quality of care (Cleary et al. 1989; Stewart 2001; Batbaatar et al. 2015). Patient satisfaction is an important indicator of quality care, although the formal assessment of such satisfaction is always going to be complex (Cleary 1998; Al-Rubaiee 2011). Several variant factors have an impact on specific patients and their responses to the quality of their healthcare, including their characteristics, attitudes, and prior experience (Oberst 1984; Blanchard et al.1990). A hospital may be well organised, ideally located, and well-equipped, but low patient satisfaction may still indicate it is failing to provide effective healthcare (Donabedian 1988; Draper et al. 2001; Turhal et al. 2002; Barlesi et al. 2005).

The enhancement of patient experiences of healthcare services is a key goal of improvement initiatives (Umar et al. 1995; Alturki and Khan 2013; Mohamed et al. 2015). Although the concept of patient satisfaction is complex and difficult to measure in terms of healthcare, patient surveys and self-reported outcomes have been successfully used in hospitals. They are perceived as the best quality indicator tools in hospital-based care settings (Ervin 2006; Lynn et al. 2007; Groene et al. 2008; Copnell et al. 2009). Although there is evidence of success found in self-reported outcomes, various studies (Sait et al., 2014, Stavropoulou, 2010; Al-Sakkak, 2008) have reported that many patients report satisfaction with ineffective care allotted to them. Al-Sakkak (2008) and Stavropoulou (2010) assert that many patient experience surveys may indicate satisfaction with ineffective care due to the literacy of patients being low and inadequately understanding the survey to provide an opinion on the quality of healthcare they received.

Self-reported studies of patient satisfaction are usually conducted through hospital self-assessment. This method of measuring patient satisfaction uses a set of devised questions which assesses the functions, procedures, and capability of the hospital infrastructure, staff, and policies. The results of the hospital assessment survey are then used to measure the delivery of health care and predict patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction questionnaire forms are an instrument used to measure patient satisfaction with a set of questions that ask the patient to comment with their opinion on the healthcare that has been provided to them. Other patient satisfaction surveys are distributed to medical professionals, such as doctors and nurses to receive their opinion on the perceived level of satisfaction of patients towards health care delivery. The current study uses a patient satisfaction questionnaire, however, it differentiates from other research taken place in KSA, as viewed in the literature review in Chapter 2, as the current study uses patients within the oncology ward setting to extract information in regards to health care delivery they are experiencing instead of the use of medical professionals such as doctors.

The literature review in Chapter 2 discusses in detail ‘satisfaction’ and other methods to measure and assess patient healthcare experience as well as a discussion on various factors that may affect patient satisfaction. In particular, there appears to be evidence indicating a relationship between satisfaction and patients’ adherence to medical regimens, along with patients’ compliance with cancer treatment and improvement in health status (Ware and Davies 1983; Borras et al 2001; Westaway et al. 2003).

1.5 Overview of the study context

1.5.1 History and background of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was unified and established as an Islamic state in 1932. The presence of the two holy mosques (Makkah and Madinah) within the country means that the KSA has an influential political role in the Middle East and the wider Muslim world. The 2010 census found that the KSA had a population of 29.9 million, of whom 73% were Saudi citizens (Central Department of Statistics and Information, KSA 2010). There is substantial employment of non-Saudis in a number of sectors, including healthcare.

Riyadh is the capital and the largest city in the KSA. The population of Riyadh is just over 7 million, which accounts for 24% of the population of the Kingdom (World Population Review 2014). To place this in context, and to encourage an appreciation for how large this city is, the city has a population of almost 2 million more than the population of Scotland, which currently stands at just over 5 million (Scotland National Statistics 2014).

Religion is an important aspect of Saudi society and the culture and social norms are drawn from the Sunnah (a set of documents held to represent a model of life, detailing the actions and the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ [peace be upon him, pbuh]). In effect, observant words and actions ensure that daily life fits the teachings of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad. Specifically, the Sunnah school of thought is a reflection of the Prophet Muhammad’s public actions and private behaviour. Essentially, religion sets boundaries for what is allowed and tolerated. The KSA is overseen by the monarchy, which dominates Saudi politics, with the King and Royal Family effectively running the state. The KSA, therefore, demonstrates a cultural homogeneity that is reflected through a common Arabic language, adherence to the Sunni Hanbali school of Islam, and a common sense of national culture.

1.5.2 The KSA culture

Within the cultural context of the KSA, Islam not only represents a religious ideology but also forms the basis for a social system that defines various aspects of people’s lives. There are, however, divergences in understanding and interpretation within Islam that lead to diversity in compliance with the traditional structures of the Islamic regulatory system and levels of adherence to Islamic ideology. Beling (1980) explains that this diversity within Islamic culture is a result of differences between urban and nomadic characteristics, tribal and non-tribal features, city-dwellers and villagers, and other aspects, such as whether individuals are literate or illiterate, open-minded or conservative.

The KSA has a patriarchal social system, characterised by masculine authority over kinship family groups. This culture affords men control over women, who are considered the ‘inferior gender’, largely due to values attached to the masculine gender as providers and protectors. A lot of emphasis within the social context is placed on the need for individuals to understand and recognise the welfare of others. Saudi social lifestyles are also characterised by specific socially defined ideals for dignity and honour (Beling 1980).

1.5.3 Healthcare in the KSA

Saudi nationals are entitled to public healthcare, which is generally free. The Saudi Arabian Health System is provided by the Ministry of Health centres and hospitals, in conjunction with the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH&RC), universities, and portions of the military (MOH 2006). Relatively low numbers of Saudis are part of the Saudi Arabian healthcare workforce, which is instead heavily dependent upon workers from other countries, including India, the Philippines, South Africa, the US, and the UK (Al-Dossary et al.2008).

1.5.4 Saudisation

At this point, it is pertinent to mention the concept of ‘Saudisation’. For over a decade, the Saudi government has been attempting to address the imbalance of foreign versus Saudi nationals in the workforce (Ministry of Planning 2002b). This is an issue that is found among a number of the GCC states, such as Qatar and the UAE, where very significant ‘expatriate’ (non-national) populations have developed due to migrant labourers being brought in to fill skills gaps in key employment areas. In comparison with the UAE and Qatar, where the non-national populations are as high as 70-85%, the Saudi population imbalance is relatively moderate at only 27%. It has, however, been identified by the government as requiring a resolution.

A Saudisation programme, which focuses on increasing educational opportunities and thus employment for Saudi nationals, was introduced to reduce and reverse over-reliance on foreign workers and to recapture and reinvest the kingdom’s income (Looney, 2004). The Saudisation process has been slow, and in 2011, Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Labour introduced the Nitaqat (‘zones’) programme as a driving force toward replacing expatriate workers with Saudis in the private sector (Ministry of Labour 2009). The programme categorises companies based on their success at nationalising their workforce, and those companies failing to meet Saudisation targets are penalised (Ministry of Labour 2009). Despite the introduction of the Nitaqat programme, change remains slow. Saudi patients still receive their care within a multi-cultural environment, largely from non-Saudi (and non-Arabic speaking) healthcare workers.

1.6 Healthcare within the KSA

There is a substantial volume of literature that criticises the level of care provided to patients in the KSA, including fluctuations in facilities, insufficient access to cancer management drugs, substantial communication issues, resource challenges, and difficulties in handling necessary organisational restructuring (Almuzaini et al. 1998; Al-Eid and Manalo 2007; Elkum et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2009; Shamieh et al. 2010). Alongside this, healthcare costs in the KSA have been increasing since 1990, and a significant result of this is a shortage of resources and variations in the quality of healthcare provided (Akhtar and Nadrah 2005; Al-Ahmadi and Roland 2005; Walston 2008; WHO 2009).

These issues can partly be explained by the significant socio-economic and infrastructure transformations that the KSA has faced over the last 30-40 years, and the change in its epidemiological profile from infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies to the ‘age of degenerative and man-made diseases such as cancer and heart and cerebrovascular disease (Younge et al. 1997, p. 309).

1.6.1 The doctor-patient relationship and disclosure

Doctor-patient relationships and disclosures are considered influential factor that impacts patient satisfaction and further patient experience. The central practice in healthcare revolves around the doctor-patient relationship and becomes an imperative component to ensure the delivery of high-quality health care. According to Kelley et al. (2014), the patient must have confidence in the competence of their doctor and the patient needs to feel comfortable enough to confide in their doctor. It is obvious that within the relationship the doctor is recognised as superior to the patient due to his/her extensive knowledge and credentials in the medical field (McKinstry 1990).

Confidentiality is a major factor which influences the doctor-patient relationship as it requires that the health care provider keeps the patient’s personal health information private unless the patient gives their consent to disclose the information. Disclosure of a patient’s medical information without consent leads to a breach of confidentiality which can be tried by law depending on the laws and ethics of various countries.

The doctor-patient relationship in KSA is completely different to the ethically set standards of many Western countries. It is commonly found that many doctors practising in KSA do not follow many of the ethical values that are embraced within a general doctor-patient relationship. This commonly includes a breach in confidentially through casually disclosing patient health information. There are also instances of doctors with KSA's mentality feeling extremely superior to their patient’s causing them to not include patients’ decisions about their health. An in-depth discussion takes place in Chapter 2, Section 2.5.2 which discusses at length literature surrounding the definition of doctor-patient relationships, how the variable influences patient satisfaction, and the doctor-patient relationship experienced in KSA.

1.6.1 Cancer prevalence and care of oncology patients in the KSA

The issue of patient satisfaction in the KSA is particularly pressing in oncology wards, as the cancer rate has been rising in recent years. Even though the top five types of cancer affecting males and females, as reported by the age-standardised incidence rate (ASR), have historically been lower in the KSA compared to the USA, such differences will, according to Ibrahim et al. (2008), be less evident in the future. The incidence of cancers in KSA is likely to increase over the next two to three decades. Reasons for this include an ageing population, the recent adoption of a typically sedentary lifestyle combined with a Western diet, and an increasing number of smokers (Jazieh 2012). Moreover, a recent publication discussing the burden of breast cancer in KSA anticipates that the incidence and mortality of cases are to increase by about 350% and 160%, respectively, over ten years by 2025 (Ibrahim 2008). The reason for such a large increase in these variables may be due to an anticipated prevalence of reproductive factors associated with the increased risk of breast cancer, including early menarche, late childbearing, fewer pregnancies, use of menopausal hormone therapy, as well as increased detection through mammography, as witnessed in developed countries (Parkin and Fernandez 2006; Zahl et al. 2008).

Most significantly, the highest increase in cancer cases in the KSA is predicted for the coming two decades (WHO 2009). Consequently, there is a need for research to examine, inform and make a contribution toward improving the quality of care to meet these anticipated increasing demands. In this regard, the current study addresses patient satisfaction interfaced with the current quality of care received within oncology ward settings in the KSA.

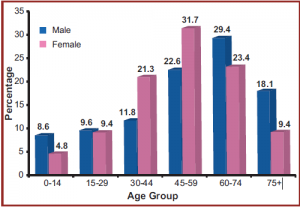

The most recent Saudi Cancer Registry (SCR) reports on cancer prevalence and rates indicate that the total number of reported cases was 13,706 in 2010 (Saudi Cancer Registry 2010). This rate is relatively evenly divided in terms of gender, with 48% of those affected being male (6,579 cases) and 52% being female (7,127 cases). Men were found to have an increased rate (up to 1.5 times the normal rate) of cancer after the age of 64, and the median ages of sufferers were calculated to be 51years for women and 58 years for men. The report also disclosed a geographical division, with Riyadh (central), Tabuk (northwest), Makkah and the Eastern Province having the highest rates, which were measured as 115.00, 92.00, 77.00 and 116.00 (all per 100,000), respectively in 2010 (Saudi Cancer Registry 2010). Further information from the Saudi Cancer Registry’s 2010 report is shown in the figure presented in Appendix 1.

It has also been reported that resources for cancer control in the KSA are inadequate and directed almost exclusively to treatment, with little focus on prevention and screening for early detection (Rastogi et al. 2004). In recognition of the problems posed by cancer, and to alleviate the suffering of people and improve their quality of life in the future, an initiative was launched in 2010 in Riyadh with the stated goal of ‘Improving Cancer Care in the Arab World’ (ICCAW 2010). This high-profile collaboration between the National Guard Health Affairs Oncology Department and the Arab Medical Association Against Cancer also includes the participation of a number of other national and international bodies. The collaboration examined a wide range of themes associated with comprehensive cancer care and control, including the role of service organisations. It was agreed to formulate a strategic planning process for the next ten years, dedicated to implementing improvements to services and planning, and exploring other issues affecting medical reform.

This huge initiative takes a holistic view, examining a range of topics, including funding, detection and screening, access to medication, and human resources development, as well as the establishment of population-based registries across all Arab countries as part of a newly developed National Cancer Control Program to enhance oncology care, generally. By illuminating the doctor-patient and nurse-patient relationship in the KSA, the current study contributes to the understanding of how these relationships operate in the KSA in particular, and Arab countries in general, with their distinct cultural beliefs.

1.6.2 Personal rationale for the study

As a former head nurse within an oncology unit in the KSA, before the current research, I was at the cutting edge of healthcare and dealt daily with a wide range of care being delivered to cancer patients. Through my hands-on experience, I witnessed areas which I believe could be changed to improve the quality of the care that patients receive. In particular, I believe that the circumstances and complexities of each patient should be considered. Such patient-centredness would help remove barriers to top-quality care and allow the patients to become empowered by allowing their opinions, feelings and perspectives to be taken into account.

However, the value of patient-centredness must be recognised before it can be effectively implemented and have a positive impact on healthcare quality. Consequently, there is a need for further research in the field to expand the knowledge base and interpret the relationship between patient experience, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. These personal perspectives and experiences have been a driving force in motivating this research. Moreover, my experiences and knowledge proved invaluable during the conduct of the current study.

1.7 Research methods

A sequential mixed-methods approach was employed to explore factors that impacted patient satisfaction as an indicator of the quality of care, using both quantitative and qualitative methods. To achieve the process of MMR process it was necessary to first conduct a quantitative phase and then a qualitative phase in which a sequential explanatory mixed methods mode was followed.

Decisions about study design were made with care. The use of mixed methods was necessary because, as noted previously, patient satisfaction is a complex construct that can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively. As Al-Rubaiee (2011) stated, patient satisfaction is ‘psychological’ and thus it is easy to understand but difficult to define; this makes the qualitative approach especially useful. According to Hudak et al. (2000) to assess patient satisfaction, it is recommended to supplement a multidimensional measure that includes global questions through direct measures with open and close-ended questions. Hudak et al. (2000) also suggested combining interview data with various survey questions as they may result in an improved understanding of patient satisfaction.

Therefore, a mixed-methods approach was used as it utilises both quantitative and qualitative methods. Generally, the quantitative approach is commonly used in clinical trials to measure different factors such as pain and disability (Hudak et al., 2000). On the other hand, qualitative data is used as it contributes to policy and practices. Usually, qualitative research includes data collection to describe and explain the meanings people assign to a particular phenomenon (Creswall and Plano-Clark 2011). The purpose of the current study was to explore patient satisfaction within oncology wards using a mixed-method design for this examination. The larger purpose of the study is to contribute to the evidence base for recommendations to be used in enhancing patient satisfaction in oncology ward settings in the KSA, and these two different methods provided wide-ranging data for in-depth analysis in terms of the research aims and questions.

In summary, in the quantitative phase, the participants completed the questionnaire on patient satisfaction to provide data on that variable’s correlations with other variables associated with quality of care, including clinical effectiveness and accessibility. This was then followed, in the qualitative phase, by semi-structured interviews to explore further the quantitative results and to seek patients’ views.

1.8 Outline of thesis

The current study is organised into six chapters.

This introductory Chapter 1 which preceded this section provides an overview of the purpose of this study. The chapter also highlights the reasons for the need of conducting this study. The chapter provides an overview of the aims of the study which will be used later to assess if the study has completed these aims.

Chapter 2 consists of a review of relevant literature related to the aims of the thesis. These include quality of care (including Donabedian’s model), patient satisfaction (including definitions, influences, and approaches to measurement), and KSA-specific studies on patient experience or satisfaction.

Chapter 3 describes the chosen research methodology and methods, and provides the rationale for adopting a sequential mixed-methods approach. This chapter also includes the processes/methods by which the research for the current study was conducted. Chapter 3 provides insights into the justification for the use of the MMR approach to complete the study.

The research findings are presented in the subsequent two chapters: Chapter 4 details the results from the quantitative phase of the study, and Chapter 5 presents the findings from the qualitative phase.

One particular challenge in a mixed-methods approach is to integrate the different strands; this is achieved in the final discussion and conclusions found in Chapter 6, which pulls together and evaluates all of the results, considers the success and limitations of the research, and offers recommendations for further study along with the contributions that the current study makes to the field of patient satisfaction in particular to the KSA healthcare setting. Chapter 6 of the current study also provides insight into the significance of the study along with the various contributions produced to improve patient satisfaction within healthcare delivery in the Saudi Arabian context. The recommendations produced by the study contribute to the improvement of healthcare systems in Saudi Arabia.

Chapter 2 - Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This review begins with a description of the methodology used in the literature search strategy, and the narrative synthesis method that is used to combine or pool the results of research studies with a range of different research designs (Coughlan et al. 2013). Then, the chapter discusses the literature on (a) quality of care and the use of the Donabedian model to define it; (b) patient satisfaction, a vital aspect of patient experience, which is a concept based on the attitudes of a patient towards their care and evaluation of the quality of care and (c) the assessment of patient satisfaction and quality of care in the KSA based on the patient experience, its factors of influence, and various means of measuring patient satisfaction in KSA along with its issues.

In the third section, which follows the discussion of the quality of care and patient satisfaction, a thorough appraisal is made of the selected literature regarding patient satisfaction in oncology settings in the KSA. A careful assessment of the most robust evidence and a detailed exploration of important and relevant themes emerging from the studies are then offered. The review concludes by identifying the limitations of existing patient satisfaction studies. These limitations are subsequently used to help formulate the research question adopted for the current study, and help to articulate the research question and the research design.

2.2 Methodology for literature review

2.2.1 Narrative synthesis

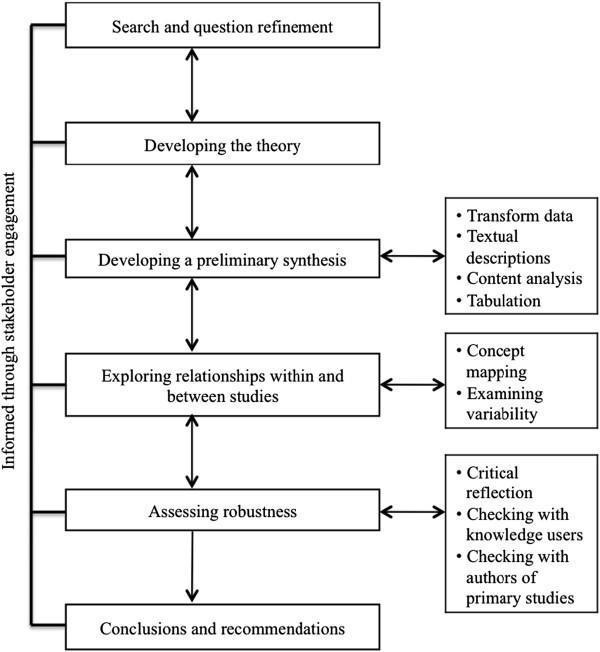

This chapter provides a narrative synthesis of existing relevant literature in the KSA and beyond, focusing primarily on publications from the last three decades, as there is little published material on the topic from before 1980. The method of narrative synthesis has been chosen from among the different methods for conducting a literature review identified by Popay et al. (2006) because it relies primarily on words and text to explain, interpret, and summarise the synthesis of findings from multiple studies which inform the research question. Narrative synthesis is a particularly useful method for facilitating evidence-informed policy development internationally (Snilstveit et al. 2012). Popay et al. (2006 p. 5) define narrative synthesis as an:

Approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that rely primarily on the use of words and text to summarize and explain – to ‘tell the story – of the findings of multiple studies.

The narrative approach to the synthesis of research evidence involves critical appraisal of large bodies of evidence, which can employ different research designs, including qualitative and/or quantitative, or a combination of both - mixed methods. The narrative approach is particularly relevant to synthesise diverse evidence from a range of study designs, as is the case here. It is noteworthy that, unlike the commonly used specialist synthesis methods, narrative synthesis has not been well developed. For example, one particular weakness of narrative synthesis mentioned in the literature is the lack of transparency (Dixon-Woods et al. 2005) and the lack of clarity on methods and guidance on how to conduct such a synthesis (Mays et al. 2005).

However, within the past decade, extensive work by Popay et al. (2006) has culminated in published guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis. This guidance shows researchers precisely how to conduct narrative synthesis systematically and transparently by focusing on the synthesis of evidence, the effectiveness of interventions, and factors determining the implementation of interventions. This guidance has been tested by other researchers and found to be robust and transparent (Arai et al. 2007; Rodgers et al. 2009). It has, however, been emphasised that researchers should ensure their narrative synthesis is aimed at producing a reflective account, rather than simply providing a summary of research findings (Rodgers et al.2009).

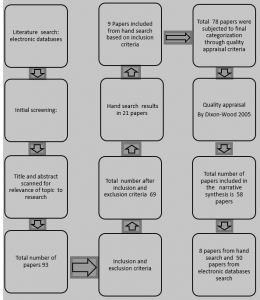

Applying this guidance to the current research ensured effective implementation of the technique. Specific tools to assist in the synthesis were adopted, and the narrative synthesis was followed. First, the approach involved setting out the adopted search strategy and describing the reasons for including particular articles. Second, theories were developed and a preliminary synthesis of the most robust research evidence was performed. This was then followed by an evaluation and a reflective account of those articles selected for inclusion. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are offered. The process is shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Integrative narrative synthesis process (adapted from Popay et al. 2006)

2.2.2 Literature search strategy

The selection criteria used for this review were applied in two stages. The initial selection of studies was followed by a final selection of the studies after an appraisal of quality. As previously mentioned, the literature search was kept within the date range of 1980-2014, as there is little published material on the topic before 1980. This also covers the period during which there was a substantial socio-economic change in the KSA, as discussed previously.

Multiple databases were searched, including Science Direct; CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature); Web of Knowledge (multiple databases, including Medline); and Google Scholar. Combinations of search terms were used through the Boolean operator, including: ‘patient satisfaction AND quality of care, ‘patient satisfaction AND Saudi’, ‘Saudi patient satisfaction’ AND ‘quality of care, Saudi Cancer patient satisfaction AND quality care’, ‘quality health care AND Saudi’, ‘Doctor Communication AND Saudi AND cancer care’, ‘Communication AND Saudi Cancer care’. This search strategy facilitated the capture of all articles about quality care issues in health care, both globally and in the KSA, with a specific focus on oncology patients. In addition to this database search, other documents and reports were accessed via the Saudi Ministry of Health, and Saudi Cancer Registry websites. A total of 93 papers were retrieved following this search (see Appendix 2 for the search and screening process).

2.2.3 Inclusion and exclusion of all search outcomes

Following the initial search, the next stage of the selection process was to narrow down the articles by reading through the abstracts and removing those not directly related to the current study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used for this selection are shown in Appendix 3. After this secondary review was complete, a total of 69 articles were selected for a full review. The importance and value of hand searching during systematic reviews are demonstrated by Armstrong et al. (2005) who use the same criteria as described for the current study. Therefore, a further 21 additional articles were selected by hand searching the citations from the initially selected articles and identifying those articles considered of relevance. These were subsequently narrowed down to nine. Accordingly, a total of 78 papers were ultimately collated and subjected to a quality appraisal.

2.2.4 Quality appraisal

To determine the quality of these extracted papers, all of the 78 identified primary studies were further subjected to rigorous quality appraisal using the method devised by Dixon-Woods et al. (2005). This approach does not exclude weaker studies but gauges the overall quality of both quantitative and qualitative papers to be graded together using the following five criteria: (1) aims and objectives, (2) research design, (3) methodology, (4) findings, and (5) interpretations and conclusions (see Appendix 4). One point is given for each of these aspects, and a research paper’s quality is judged in terms of the total score obtained out of five. Of the 78 papers, those obtaining the highest quality appraisal rating were included in the final review. These papers were scored in the following way: 3, if they omitted a robust explanation of the methods used such as the sampling strategy or the instrument definition; 4 if only a clear interpretation of the results was missing; and 5, if they addressed study aims, methods and findings. As a consequence of this screening, a total of 58 papers were selected for use in this review.

2.3 Overview of studies

This section presents an overview of the studies reviewed. The details of the 58 papers that were selected and critically reviewed can be found in Appendix 5. Appendix 5 includes a summary of study aims, sample population, methods, key findings and limitations of the studies for each paper. A preliminary synthesis helped develop theories regarding patient satisfaction; further critical review then allowed exploration of relationships within and between studies. This iterative process identified a number of common themes and allowed for the categorisation of several identified variations. The rest of this chapter presents the narrative synthesis of the research on the quality of care, patient satisfaction, and healthcare in the KSA.

2.4 Quality of Care: Definition and Measurement

Quality of care is an increasingly important concept in health care. However, it has proved a very difficult concept to measure and quantify given its highly subjective nature (Cleary 1998; Campbell et al.2000; Ladhari 2009; Beattie et al. 2014). Therefore there is a need for a working definition that can capture the multidimensional nature and reflect the differing perceptions of what comprises quality of care. The Institute of Medicine IOM (2001) define quality as ‘the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge (IOM 2001, p.65). This definition suggests that if patients can access the services they need and if the services provided are useful then quality is guaranteed. Therefore, this working definition is adopted in the current study.

The traditional method of measuring the quality of health care was assessing if the care or treatment being provided had achieved its goal, for example, was the illness was cured, did the patient recovered (Payne et al. 2001). Today a more holistic approach is taken to the issue of quality of care. Quality of care is ultimately how patients reflect upon their experiences in a health setting and if they positively construct them. Therefore the quality of care is ultimately determined by the patient and this is crucial to a patient-centred approach (IOM 2001). Quality of care usually involves more than successfully treating a patient and is related to the overall experience of a patient (Tsianakas et al.2012; Manary et al 2013; Beattie et al. 2015). An important theme that emerged in the literature review was the wide range of components of care and the differing extents to which they have received attention. This raises the issue of the identity of the indicators we need to consider as essentially linked to the measurement of quality to assess patient satisfaction.

The most frequently identified dimensions of quality in literature are safety, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness and timeliness (IOM 2001; WHO 2006; Copnell et al.2009; Beattie et al. 2015) all of which will be reviewed in the current study’s literature review section. . Campbell et al. argue the vital importance of effectiveness as a major criterion for measuring the quality of care as effectiveness is related to all clinical aspects of health care delivery. However, the focus of the current study is to assess patient satisfaction through understanding patient experience in oncology wards in the KSA healthcare settings. For this purpose, all six quality dimensions identified in the literature will be assessed.

2.4.1 Donabedian model

The Donabedian model (1980) provides a framework to understand the quality of care in a healthcare setting. It does not claim to offer how an organisation can improve the quality of care, or even present a definition of what quality of care is, but rather should be seen as a way of helping to evaluate it. The Donabadian model offers a way of analysing a health care environment or a treatment method to determine what can be done to understand the level of quality of care for patients. Information on patients’ satisfaction with the quality of care can be assessed with the help of information captured under three domains (1) process, (2) structure, and (3) outcome which for the current study are used in combination with IOM’s (2001) six dimensions of quality which includes safety, effectiveness, equity, patient-centeredness, efficiency, and timeliness. The information captured under these domains is all specific to aspects of care including quality found throughout the healthcare system. The structure is the context and environment in which the care is provided. This can include the buildings, equipment and staff. Process refers to the various actions and initiatives taken in the treatment of a patient and includes all the actions involved in the care of a patient from diagnosis to aftercare. It includes clinical and interpersonal aspects of care during the delivery of medical treatment or intervention. Outcome refers to the series of consequences and effects of the treatment on a patient. This is possibly the most important of all the concepts in the Donabedian Model. It is ultimately the main criteria for a patient’s level of satisfaction with the care received.

The Donabedian Model does not try to measure the quality of care; rather it provides a theoretical framework that allows professionals to examine the factors involved in the quality of care for patients. There is a strong relationship between all three domains as suggested by Donabedian (1980) and all need to be explored together (Khmais and Njau 2014, p. 6). For example, the Donabedian Model was used as a basis to construct reliable findings on patients’ satisfaction in an outpatient setting in Dar Es Salem Tanzania (Khamis and Njau, 2014). The model has been widely used as the basis for identifying quality in international healthcare settings (Tarlov et al. 1989; Irvine and Donaldson, 1993; Campbell et al. 2000; Kringos et al. 2010). The model has been used to generate data and insights into patients’ quality of care and provides concepts useful in identifying factors that influence patients’ satisfaction and has been useful in the current research

2.4.2 Influence of Donabedian’s model

Debates and findings in the literature regarding the quality of care demonstrate the widespread influence of the Donabedian model and appear to centre upon organisations’ service structures and processes, plus doctors’ and nurses’ skills and availability (Chassin and Gavin 1998; Copnell et al. 2009). In a study on quality of care in hospitals by Copnell et al. (2009), indicators were first classified based on aspects of care provision (structure, process, and outcome), then according to the dimensions of quality (safety, effectiveness, equity, patient-centeredness, efficiency, and timeliness), followed by the domain of application using the Donebedian’s model, including hospital-wide surgical and non-surgical clinics. The study of Copnell et al. (2009) found that while there were a large number of available indicators, there were instances where they were not applicable and inadequately measured the quality of care, and further studies were needed to determine which of the existing indicators are pertinent.

Research suggests that the structural aspects of healthcare have implications for patient satisfaction. Structure of care refers to ‘the organizational factors that define the health system under which care is provided (Campbell et al. 2000 pp. 1612). A key domain of a healthcare delivery system is how it is structured to involve service organisations or access to services in the healthcare facility (Donabedian 1980; Davies and Crombie 1995; Campbell et al. 2000; Sizmur and Redding 2009). This includes the ease and rate of the movement of patients from one facility to another, the availability of services, such as screening and testing, the effectiveness and organisation of the schedule that the patients have to follow, and the overall experience of the patients during their time in health care. Patients’ experiences of access to services, which include service organisations and structures, can significantly contribute to patient satisfaction, which is one of the key indicators of quality of care. Hence, assessing access to services represents a further dimension needed to meet the aims of the current study.

Research further suggests that the processes by which healthcare is delivered are related to patient satisfaction. According to Campbell et al. (2000), Donbedian’s process of care ‘involves interactions between users and the health care structure; in essence, what is done to or with users’ (pp.1612). Of fundamental importance to processes of care is clinical effectiveness, an important criterion for patient satisfaction (Schuster et al. 2005; Campbell et al. 2009). Clinical effectiveness is the delivery of suitable patient care suitably by health professionals with the best outcome possible for the patient and their wellbeing (Doyle et al, 2013).

Studies by Cleary and Edjman-Levitan (1997), Chassin and Gavin (1998), and Campbell et al. (2000) describe a plethora of different quality indicators with little standardisation. A study, undertaken by Bredart et al. (2007), using the EORTC INPATSAT32 questionnaire, found that the most relevant indicators of quality were the interpersonal skills and availability of nurses and doctors, and information provision. The EORTC INPATSAT32 tool is cross-culturally validated and is therefore found to be capable of judging the satisfaction level of patients from different cultures. The difficulty in measuring the quality of care was confirmed by some studies to be due to a lack of a standardised definition of what comprises quality and how best it can be measured (Mainz 2003; Groene et al. 2008). Mainz (2003) differentiated quality based purely on structure (number of specialist doctors available, access to equipment and tests, access to specific units, etc.), process (protocols and procedures that were used in treatment and care), and outcome (mortality, health status, satisfaction and patient quality of life). From the consensus in the literature, it is now clear that when considering the patients’ perspectives of their care, a range of influencing factors, including social-political, social-cultural, and socio-demographic, must be considered. Given the difficulty of defining and measuring the quality of care, it stands to reason that it would also be difficult to measure patient satisfaction, the construct at the heart of the current study. However, the indicators discussed above in the Donabadian model allow for parameters to be established to allow the issue of patient satisfaction to be explored.

2.5 Patient satisfaction

This section discusses the literature on patient satisfaction, including (1) the varying definitions of the construct of patient satisfaction, together with (2) the wide array of factors that have been shown to influence it, and (3) the various approaches that can be used to attempt to measure it.

2.5.1 Definitions

The concept of patient satisfaction has evolved over the years as different definitions have been applied to the concept. Linder-Pelz (1982) defined patient satisfaction as an evaluation of distinct health care dimensions. Pascoe (1983, p. 189), on the other hand, defined it as a ‘comparative process involving both cognitive evaluations of care and an affective response that may include both structure process and outcomes of services. Keith (1998, p. 1122), defined patient satisfaction ‘as a complicated multidimensional concept whose measurement and application are anything but simple. A more recent definition by Al-Rubaiee (2011) refers to it as a psychological notion that is easily understood but difficult to define. Patient satisfaction is considered an imperative and generally used indicator for measuring the quality of healthcare delivery. Prakash (2010) has argued that patient satisfaction impacts clinical outcomes, patient retention, and medical malpractice claims. Furthermore, it is known to affect the judiciously, efficiently, and patient-centred delivery of quality health care (Prakash 2010). As a proxy, patient satisfaction is considered a very effective indicator used to measure the success of doctors and hospitals. Generally, patient satisfaction is used as a performance indicator commonly measured in self-reporting studies and at times particular kinds of customer satisfaction metrics (Farley et al. 2014). William (1994) and Farley et al. (2014) have countered the effectiveness of patient satisfaction as a useful tool of measurement by arguing that many times self-reporting assessments are unable to measure the extent to which a patient may be content with the healthcare that they are receiving. They argued that metrics implemented may not be valid as patients may be dissatisfied with health which improves their health or satisfied with health care which does not. Various studies have failed to identify the relationship between satisfaction and health care quality including Schneider et al. (2001); Avery et al. (2006); Clarke et al. (2006); Chang et al. (2006); Sack et al, (2011); and Solberg et al (2011);.

These definitions developed through the various literature that has been analysed identify patient satisfaction as a multidimensional concept determined by the individual views of patients asked to complete a questionnaire evaluating the adequacy of care services they have received.

Traditionally, patient satisfaction is largely determined by patients’ evaluation of their experiences, across a range of key variables, especially outcomes. This view of patient satisfaction is often regarded as a flawed concept if it is simply based upon perceptions of quality of care. More recent research on patient satisfaction is now increasingly linked to how they constructed their experiences (Davies et al.2011; Anhang Price et al. 2014). Patient satisfaction is no longer just based upon patients’ ratings of their care but on how they have conceptualised it. That is how they have configured their experiences into a belief or idea that their experiences were positive or negative. This construction involves ‘their multiple satisfactions with various objects and encounters that comprise their care’ (Singh, 1989, p. 177). Patient satisfaction is the conceptualisation of their experiences as good or bad and the extent to which this concept is positive or negative determines their level of satisfaction. Patient satisfaction is distinct from their experiences, although dependent upon those experiences. Patients’ experiences are the encounters with healthcare professionals in a healthcare setting. In other words, it is the sum of all interactions that are shaped by a healthcare organisation’s culture, that influence the patient perceptions throughout the continuum of care (Solberg et al. 2011). Satisfaction is the conceptualisation of the totality of their experiences in a health care setting which is influenced, but not determined, by one experience. Patient satisfaction is defined as the evaluation of the conceptualisation of their experiences and the extent to which it has satisfied their needs and has delivered the expected outcomes (Jekinson et al.2002). This working definition is adopted throughout the thesis.

Central to patient satisfaction are patient expectations. Satisfaction in the clinical setting can be defined simply as the desirable outcome of care, while perceived service quality refers to the process where the consumer (in this case the patient) compares his/her expectations with the service he/she has received, which, in this case, is a subjective measure (Gronroos, 2000). Smith (1992) likewise recognises the subjective nature of patients’ evaluation of care, thus illustrating the complex interrelationship between perceived need, the expectation of care, and the experience of care. Indeed, patients’ expectations of care are known to be influenced by several factors, including patient characteristics, prior experience and characteristics of the situation, as well as environmental factors (Oberst 1984). Expectations predispose a patient to have a positive or a negative experience. Satisfaction levels are related to whether a patient’s expectations are met when they encounter the health care system (Bowling et al. 2013). The extent to which a patient’s expectations have been acted upon or not influences the development of their experience in a healthcare setting which later significantly influences their development of a specific level of satisfaction ( Bowling et al. 2013).

Customer and patient satisfaction constructs are only similar in that they both value the process by which services are delivered. For a patient, service delivery includes medical care as well as provision of comfort, emotional support and education (Kupfer and Bond 2012). Also, there is a suggestion that to satisfy patients continuously, there is a need for physicians to incorporate patient perspectives into the clinical decision-making process. Patient satisfaction can be misinterpreted as there is more to it than a health service provider offering high standards of care and ignoring individuals’ perspectives. Good quality health care by itself does not guarantee that patients evaluate their experiences in a positive light. Findings in the literature recognise the need to differentiate between the two concepts of quality health care and patient satisfaction (Cleary 1998; Haddad et al. 2000). Al-Rubaiee (2011) describes satisfaction as a moving target that must be monitored to understand the content of patient expectations and ensure health care providers respond proactively to enhance the standard of care provided to patients. In other words, patient satisfaction should be supported by abilities and a need for ongoing evaluation of the quality of care to identify opportunities for service or care innovations.

A review of the literature has shown that patient satisfaction is affected by the model of patient-centred care adopted (Brown et al. 1999; Mead and Bower 2000), and evidence has suggested that the underlying notion of what patient-centred care means has implications for patient satisfaction (Michie et al. 2003; McCormack et al. 2011; Kupfer and Bond 2012). However, there is a dearth of literature related to patient-centred care in the KSA. The literature that does exist suggests that the adoption of patient-centred care in the KSA can help bridge the gaps related to information provision resulting from cultural beliefs (Younge et al. 1997; Al-Ahwal 1998; Aljubran 2010).

2.5.2 Influences

Various factors influence patient satisfaction which will be discussed in extensive detail in the following sections. To review, patient satisfaction found in the health care services setting is dependent on factors of healthcare service duration and efficiency of care, the empathy and communication that health care providers give. Evanschitzky et al. (2011) assert that patient satisfaction is seen to be favoured by a good doctor-patient relationship. Mittal et al. (2007) have argued that patients who are well-informed about the process and procedures within a clinical encounter and the amount of time that the processes will take are generally seen to be more satisfied with the service even if they must wait longer. Mittal et al. (2007) also argue that one of the most influencing factors of patient satisfaction is the job satisfaction that is experienced by the healthcare provider.

The research suggests that a variety of different factors influence patients’ perceptions of their experiences in a health care setting, although patient satisfaction is generally difficult to isolate from overall clinical outcomes. This section starts by discussing several cultural and demographic influences more generally and then focuses on specific influences that are found consistently in the patient satisfaction literature: disclosure practices, gender politics, respect for patients’ religious beliefs, the doctor-patient relationship, and the practice of patient-centred care. Afterwards, each of these particular influences is discussed and analysed through the KSA patient satisfaction and experience.

The influences on patient satisfaction are difficult to separate from overall clinical outcomes for several reasons. According to Jackson et al. (2001), the psychological determinants that may lead patients to express themselves as being relatively satisfied or dissatisfied remain largely unknown, a point reiterated in the literature reviewed in this section. To attempt to bring some clarity to these important areas, Jackson et al. (2001) set out to establish which characteristics of patients (and physicians) correlate with expressions of satisfaction, and what the contribution of the many satisfaction variables identified in previous studies may be, and the extent to which the co-relationships remained constant over time. They found that patients over sixty-five years old are more likely to be generally satisfied; however, the most important predictor of satisfaction, according to them, was the meeting of expectations. This supports the findings of Hall and Dornan (1990), who found that higher levels of satisfaction were associated with increased age.

Indeed, considerable research exists indicating older patients tend to be more satisfied with their health care, a phenomenon which is consistent across cultures and nations (Campbell et al. 2001; Crow et al.2002; Jaipaul and Rosenthal, 2003; Sofaer and Firminger, 2005; Moret et al.2007; Quintana et al.2006; Bleich et al. 2009; Rahmqvist and Bara, 2010; Lyratzopoulos et al. 2012). This may arise from older people having lower expectations of the health care system and therefore there is less likelihood of their expectations being unmet. However, some researchers maintain that these findings may be flawed and not a true reflection of reality due to an inherent caution and reluctance of older people to voice their dissatisfaction when questioned about the adequacy of their health services as they are in constant need of them (Bowling, 2002; Bowling et al. 2013). Finally, the findings of this review suggest that there has been little research on the demographics and other patient characteristics as determinants of patient satisfaction in KSA oncology settings; this is an area warranting increased attention.

2.5.2.1 Disclosure practices

An important cultural issue that may impact patient experiences and their reflections on them is disclosure. Research in Japan by Tanaka et al. (1999) found that patients suffering from terminal cancer wanted clarity on their prognosis so that they could make the best use of their time. The study argued that it is a basic human right of an individual to know about his/her prognosis.

Concealing the diagnosis from cancer patients may lead to poor patient compliance, misinformation of treatment options, and side effects, which could hurt the patient’s survival and remaining quality of life. However, even where disclosure occurs, cultural barriers can exist because of a reluctance to accept a terminal prognosis. This puts health care providers in a complex situation, as they are expected to be sensitive toward the patients and their needs as well as continue the care, despite their professional judgment (King et al. 2008). In this regard, it is important to have quality palliative care along with effective coordination between the primary, secondary, and tertiary care services.

2.5.2.2 Doctor-patient relationship

Research further suggests that the doctor-patient relationship is an indicator of patient satisfaction. The encounter between practitioner and patient is valuable for defining patient evaluation of the quality of care and can be seen as fundamental to the doctor-patient relationship (Ong et al. 1995). Although patient-centred communication is at the heart of such interactions, there are different levels and types of communication. These have been separated into three areas by Ong et al. (1995): (1) the creation of good interpersonal relations between the doctor and the patient, (2) the exchange of information, and (3) the making of decisions which are related to the treatment. Ong et al. (1995) found that the extent and type of communication used by the doctor and the responsiveness of the patient will subsequently have a strong impact on the levels of satisfaction derived by the patient from the interaction. Improvements in the doctor-patient relationship will directly influence the quality and levels of patient-centred care, and in the long term, improve patients’ evaluation of their experiences.

In a study of how to improve health through communication, Street et al. (2009) identify seven pathways for doing so: (1) increased access to care, (2) greater patient knowledge and shared understanding, (3) higher quality medical decisions, (4) enhanced therapeutic alliances, (5) increased social support, (6) patient agency and empowerment, and (7) better management of emotions. In another study emphasizing the importance of doctor-patient communication, Kenny et al. (2010) state that good communication is essential if the notion of ‘relationship-centred care is to be encouraged. Their results show some significant differences between what patients perceive as the communication skills of the doctors and the doctors’ perceptions of those skills. The qualitative research by Jagosh et al. (2011) reveals that doctors’ listening to patients is a critical part of the communication process. These results echo the Institute of Medicine’s (2001) claims about the alignment of care to the ‘voice of medicine’ as part of the patient-centred care approach.

These studies demonstrate a clear connection between communication and a successful doctor-patient relationship, and there is some evidence that the more the emotions of patients are satisfied by the doctor through effective and considerate communication, the higher the levels of satisfaction generated. However, there is also evidence that the effectiveness of this relationship appears to depend on the severity and associated psychological condition of the patient (McWilliam et al. 2000; Ong et al. 2000; Street et al. 2009; Jagosh et al. 2011). In other words, whilst a correlation seems to exist between communication and patients’ satisfaction levels, the strength of this correlation remains equivocal and is a subject for further study.

During the past four decades, there has been a transition in the doctor-patient relationship from one in which the decisions of doctors were ‘silently complied with, and any information imparted by the doctor was designed to support his or her opinion of the most suitable course of treatment, to one in which the patient has an expectation of being at the centre of the process and anticipates a greater level of “mutual participation” (Kaba and Sooriakumaran, 2007, p. 57). This shifting relationship reflects not only a change in the socially constructed view of how patients should be empowered but also one which has been encouraged by the ‘social system’. This means that a patient-centred approach has become the predominant model in clinical practice today. However, the KSA is just starting to address the need to improve doctor-patient communication (Aljubran, 2010), and this aspect of research forms an important element of the current study. The next section discusses patient-centred care in greater detail.

2.5.2.3 Patient-centred care

Generally, patients’ development of their experiences based upon their care may involve complex processes and may be influenced by the values and beliefs of each patient, along with other variables such as health status and socio-economic status. A further factor frequently mentioned in the literature on patient satisfaction is patient-centred care (De Silva, 2014). Within the UK, the need for a patient-centred health system is widely accepted, since this approach supports people in making informed decisions about their health and care, hence, facilitating appropriate management of their care (De Silva 2014). The need for patient-centred care is also well-recognised globally (IAPO 2006; WHO 2008), and in 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted it as a major goal for improving health care in the USA. The IOM report defines patient-centeredness as ‘providing care that is respectful of and representative to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions (IOM 2001, p. 3). Kupfer and Bond (2012, p. 139) describe patient-centred care as ‘improving health literacy through information and education, coordination and integration of care, physical comfort, emotional support, and personalised care, which encompasses the concept of shared decision making. It can be argued that achieving a better experience for a patient and therefore higher patient satisfaction levels involves good patient-centred care (Krupat et al. 2001; McCormack 2003).

The ascent of patient-centred care in recent years has been driven by the recognition that care can often be more effective when it is tailored to specific patients’ needs (Gill, 2013). Patient-centred care in the literature is very much focused on the individual, the delivery of whole person-care and communication. This form of care encourages the participation of the patient and their family in the decision-making process about treatment. Although researchers disagree on what exactly constitutes patient-centred care, and its influence on patient satisfaction has not been firmly established, ample evidence does suggest that patient-centeredness leads to patients reflecting upon their experiences in a health care setting in a positive way. Patient-centred care is still fairly new in the Saudi healthcare delivery system due to societal norms that influence doctors' and nurses' perceptions.

Indeed, the literature reveals the existence of several definitions for patient-centred care and, largely as a result of this; there is a range of approaches available for measuring patient-centred care. Most take a holistic view or measure specific subcomponents such as shared decision-making or communication (De Silva 2014).

2.5.3 Factors influencing patient satisfaction in KSA studies

Throughout the literature, strong patient care has been established as a strong indicator of PCC but it is very little to no literature available of evidence of PCC in KSA. In the KSA, other influences have also been identified, such as culture and language differences between KSA nationals and health care practitioners, and these have been found to affect the perceived quality of care patients receive. This is largely influenced by the fact that the nursing workforce in the KSA relies mainly on expatriates who are recruited from different countries such as India, the Philippines, South Africa, North America, the United Kingdom, Australia and the Middle East countries (Luna 1998; Tumulty 2001; Aboulenien 2002). One study showed that the language and cultural differences of the expatriate nurses may cause Saudi patients to encounter barriers to communication during health care (Al-Dossary 2008). Thus, the challenge for the KSA is to increase the proportion of Saudi nurses in the workforce to deliver culturally sensitive care, further facilitated by all nurses having a command of the Arabic language used by Saudi patients (Al-Dossary 2008). This would enhance the experience of patients and allow them to construct their experiences positively. Notably, however, an earlier study argued that language differences between patients and nurses do not impact the satisfaction level of the patient (Ibrahim et al. 2002). These findings call for more research into KSA patient satisfaction, specifically in terms of language and cultural differences between patients and nursing staff.

Other factors highlighted as potentially affecting patients’ perception of their experiences and the subsequent level of their satisfaction with care in the KSA are political-social, age, or educational issues. Patients who are better educated but have poor health are more dissatisfied than those who were less educated and in better health ( (Alborie and Sheikh Damanhouri 2013). Also, older patients tend to be more satisfied with the service quality than those in their twenties ( Alsakkak et al.2008 ). This may be related to the previously mentioned transformation in the economic climate in the KSA. Older people may be more accustomed historically to living in austere conditions and therefore have lower expectations of the healthcare system and are appreciative of whatever care they receive (Bowling et al. 2013). Rahmqvist and Bara () likewise identified patient characteristics related to patient evaluations of their experiences in a health care setting, namely age, education and health status.