The Impact of Corporate Governance on Financial Performance of SMEs: A Case of SMEs in the Retail Industry in Nairobi CBD

December 13, 2022

Arsenic Contamination of Environment

December 14, 2022Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) offers a constructive lens for resolving conflicts outside traditional courtroom settings. By fostering mediation, arbitration, and negotiation, ADR provides a more flexible and efficient avenue for parties to reach mutually acceptable solutions, promoting a quicker and often less adversarial resolution process.

Conflicts inevitably surface in the intricate web of human interactions—a contractual disagreement, a workplace dispute, or a familial discord. However, the conventional legal system can often appear as an intimidating and protracted route to resolution. The labyrinthine court procedures and the adversarial nature of litigation may exacerbate tensions and prolong the path to reconciliation. Recognizing the need for a more streamlined and cooperative approach, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) emerges as a beacon of change. ADR comprises diverse methods designed to usher parties away from the conventional courtroom drama, offering them a more flexible and efficient means of settling differences.

Enter Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), a set of methods that offer a refreshing departure from the courtroom drama and provide parties involved in disputes with more flexible and efficient ways of settling differences. In contrast to the rigidity of traditional litigation, ADR introduces adaptability into the conflict resolution process. Whether through mediation, arbitration, or negotiation, ADR allows parties to tailor the resolution procedure to their unique needs and circumstances. This flexibility expedites the resolution process and fosters a collaborative atmosphere, encouraging open communication and compromise. As we navigate the complex terrain of conflicts, ADR stands as a promising alternative, steering us toward a more harmonious and timely resolution of disputes.

Abstract

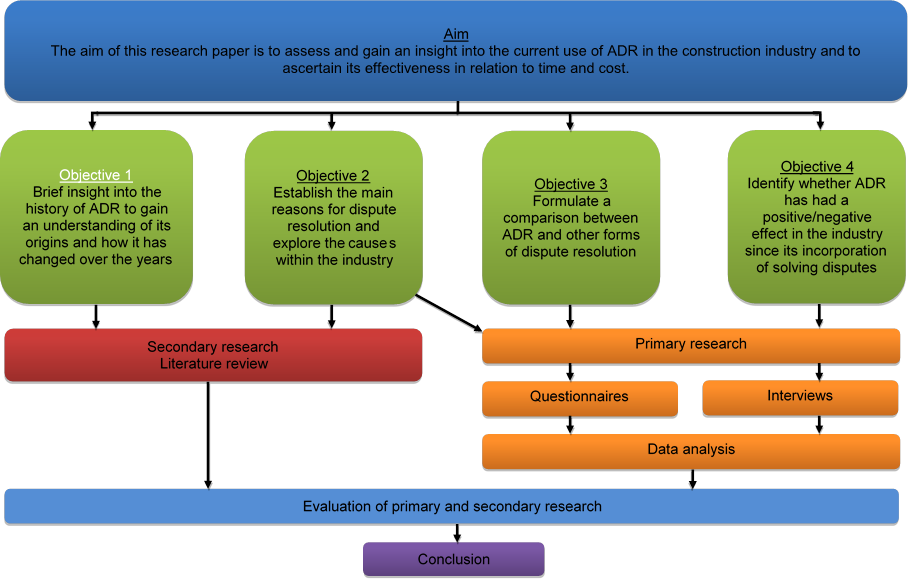

This thesis delves into the challenges and conflicts of the construction industry arising from its dynamic and ever-evolving nature. The complexity of construction contracts often leads to disputes among the various stakeholders involved. Construction professionals conducted semi-structured interviews and administered questionnaires focusing on alternative dispute resolution (ADR) to address this issue. The primary objective was to assess the correlation between cost and time within the ADR sector, comparing its impact to traditional methods. Additionally, the study aimed to identify the types and frequency of conflicts and factors influencing the transition into disputes.

The research encompasses an in-depth literature review, summarizing key definitions of disputes and conflicts. It also provides a brief historical overview of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) and its evolution into a standard form of contract and primary method of dispute resolution. The literature review further explores the applications and circumstances surrounding ADR processes. Subsequently, the findings from the literature review, semi-structured interviews, and questionnaires were triangulated to draw conclusions and formulate recommendations.

The key findings highlight that conflicts and disputes are intrinsic to the construction industry due to its intricate nature and the many interdependent parties involved. These conflicts can arise at any stage of the construction process, extending even before the commencement of design work. Moreover, the study reveals that ADR, compared to litigation, is more effective and efficient in terms of time and cost. However, it emphasizes the continued relevance of legal proceedings to prevent disputes from spiralling out of control regarding costs.

The research also identifies the most common causes of disputes. The literature review and primary data analysis consistently highlight recurring causes over the years, suggesting a potential correlation that warrants further investigation. The solutions proposed, such as early intervention in conflict, demonstrate significant potential to impact cost savings, time efficiency, relationship preservation, and the overall trajectory of dispute development.

Acknowledgements

In the acknowledgements, heartfelt gratitude is extended to the individuals whose unwavering support and contributions played a pivotal role in completing this thesis. Their guidance, encouragement, and valuable insights have been instrumental in shaping this scholarly endeavour.

Declaration

I affirm that the content presented in this dissertation results from my original and independent work, and I unequivocally assert that no portion has been borrowed or replicated from any external source. Appropriate citations and referencing have been diligently applied when I have incorporated other authors' ideas, theories, or concepts.

This dissertation stands at ____________ words approximately.

Signed:

Print Name:

Date: ___________

Abbreviations

ADR – Alternative Dispute Resolution

NBS – National Building Survey

EOT – Extension of time

TCC – Technology and Construction court

LADs – Liquidated and ascertained damages

RICS – Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors

L&E – Loss and Expense

FAV – Final Account Variation

VOV – Valuation of Variations

FTU – Failing to understand

CPR – Civil Procedure Rules

HGCRA - Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act

ANOVA – Analysis of Variance

GCDR – Global Construction Dispute Report

NCCLS - National Construction Contracts and Law Survey

Introduction

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) offers a more effective approach to resolving construction disputes than traditional litigation methods. ADR methods, such as mediation and arbitration, provide avenues for dispute resolution, while some disputes may still necessitate formal litigation procedures.

In the construction industry, where diverse individuals from various corporations collaborate, disputes are almost inevitable due to the industry's dynamic nature. ADR techniques have gained traction as a preferred means of managing conflicts and disputes, largely because traditional methods incorporated into standard contract forms have proven unsatisfactory (Lee, WingYiu, & Cheung, 2016).

Distinguishing between conflicts and disputes, Fenn, Lowe & Speck (1997) note that conflicts arise when the interests of two parties are incompatible and can often be managed to prevent disagreements. On the other hand, disputes, as highlighted by Cakmak & Cakmak (2014), become a significant hindrance to project completion and necessitate resolution through mediation, arbitration, negotiation, etc.

The primary catalysts for construction disputes revolve around financial and temporal factors, such as non-payment and delays due to adverse weather conditions. These issues can lead to project setbacks, prompting potential claims for extensions of time (EOT) and loss and expense claims, depending on the responsible party, whether the employer or contractor.

Hypothesis

ADR has enhanced the efficiency of dispute resolution in terms of cost and time due to its alternative approaches.

Negative Hypothesis

Despite using alternative methods, ADR has not proven to be more effective in terms of cost and time for settling disputes.

Research Primary Aims

- Investigate ADR to gain insights into the motivations driving its utilization.

- Explore and identify the primary techniques employed in ADR.

Research Objectives

- Provide a concise overview of the historical evolution of ADR to comprehend its origins and evolutionary changes.

- Examine the primary causes of disputes within the construction industry and establish the key factors contributing to these conflicts.

- Conduct a comparative analysis between ADR and alternative dispute resolution methods.

- Evaluate the impact of ADR on the construction industry, discerning whether its incorporation has resulted in positive or negative effects in resolving disputes.

Research Methodology

The literature review plays a pivotal role in validating the viability of the proposed hypothesis. The initial step involves exploring alternative dispute resolution (ADR) extensively to familiarize the author with the subject and refine the thesis's aims and objectives. Torraco (2016) recognizes that literature reviews serve diverse purposes and adopt varied forms for different audiences.

After conducting thorough research and establishing foundational knowledge, the literature review will be crafted to provide the author with a comprehensive and current understanding of the subject. This review will draw upon a substantial body of secondary data, including journal articles, written works from books, and research from the World Wide Web.

Quantitative or Qualitative Strategy

Two distinct research strategies and methodologies fall under 'Quantitative' and 'Qualitative' (Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016). The selection of a research methodology is contingent upon the study's purpose and the type of data needed (Naoum, 2013). Table 1 delineates the essential characteristics of both types and their respective research approaches.

| Aspect | Quantitative | Qualitative | |||||||

| |||||||||

Features of qualitative and quantitative approaches to research(Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016)

Quantitative Research Data

Quantitative data is measurable and normally in a numerical form that can be rigorously and statistically analysed. This can be drawn by collecting data from questionnaires, case studies, literature, etc (Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016). Furthermore, Naoum(2013) states that quantitative research clarifies a theory by analysing data through objective research.

Qualitative Research Data

Qualitative data is based on opinions, perceptions and feelings. This data is captured through interviews, discussions, observations, etc. This results in non-numerical data, i.e., it uses words, which provides more open interpretation data (Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016). Furthermore, Naoum(2013) describes qualitative research as subjective and ‘Exploratory’ when there is limited knowledge of the topic or ‘Attitudinal’ when assessing an individual’s perspective towards an object.

Primary Data

Primary data can be collected directly from the author to support the research (Naoum, 2013). This method is considered to attain the most reliable research. It gives the researcher more control over the collection of data. Furthermore, carrying out this type of research provides the author with an understanding of how real industry practices relate to the author's real-world experiences (Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016).

Secondary Data

Questionnaires are a form of research instrument that sets out a series of questions to compile data from respondents to gather opinions, feelings, and perceptions on the selected topic. Closed question questionnaires provide a predictable and simple set of answers. Closed questions are desired because a collection of answers produced in advance can be listed on the questionnaire(Brace, 2018). This type of question enables an easy way to collect data and provides an effortless way for the respondent to record their data.

Closed questionnaires will be thoughtfully written to avoid incompletion and ensure the collected data can be analysed. Fellows & Liu(2015) state the questions should be unambiguous and easy for the respondent to answer. They should not require extensive data gathering by the respondent. They will use the most widely used Likert scale and multiple-choice questions to attain accurate views and to what extent they agree/disagree with a statement. In addition, they will closely follow the objectives to ensure the thesis aims are fulfilled.

The questionnaires will aim to learn about ADR, its effectiveness compared to traditional methods, and what methods were used. Before distribution, These will be piloted to warrant their effectiveness and provide constructive feedback(Fellows & Liu, 2015). Questionnaires will be distributed to construction law sector participants with experience in alternate dispute resolution. An expectation of around 10-15 % returned and completed will suffice for suitable data analysis. The participants will be sourced via social media networks such as LinkedIn and contacts obtained during university.

Interviews

Interviews will also be conducted following the questionnaires and developed based on the questionnaire responses. The interviews aim to provide qualitative rather than quantitative data, which cannot be obtained via questionnaires alone. Interviews are verbal interactions between two or more people where information is directed from the interviewee to the interviewer (Laycock, Howarth, & Watson, 2016).

Interviews can take different forms, being fully structured, semi-structured, and unstructured. Semi-structured interviews will take place for this thesis as this type offers greater flexibility and depth in the interviewee's responses. I plan to conduct semi-structured interviews via telephone, preferably Skype interviews if possible, to allow convenience for the interviewee. I plan to carry these out with the following participants:

- Interviewee P1: Quantum Claims Consultant

- Interviewee P2: Chartered Surveyor

The interviews are expected to last around 30 minutes; however, a cap of 15 minutes is needed if needed. It is thought the participants will provide me with specialist opinions within this niche subject area. Initially, it was intended to conduct face-to-face interviews. However, most interviewees preferred telephone interviews, which they considered would be less intrusive on their time, so interviews over the phone were carried out.

All interviewees must fill out a consent form before the commencement of the interview. This will be included in Appendix 1. All interviews will be recorded via a Dictaphone, borrowed from the university, with consent from the interviewees before questioning and recording for transcription and analysis. Data analysis will be thematically analysed, and common trends in the answers will be identified within my analysis.

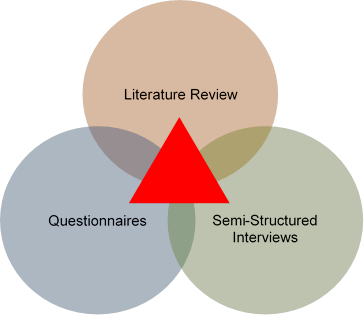

Data Triangulation

Triangulation is a research application of two or more data collection methods to ensure the viability of data and attenuate the flaws with the associated methods (Naoum, 2013). It draws upon information from different sources and people’s perspectives, i.e., literature reviews, questionnaires, and interviews, to aid in producing robust data and mitigating any flaws with each method. Using various data collection methods (figure below) increases the likelihood of any inconsistency within the data being identified; therefore, the data represents real-world opinions and has aided in robust conclusions.

Triangulation

Triangulation

Triangulation

Methodology model

Methodology model

Within the early stages of research, there were limitations recognised and considered. First was the limited accessibility of current research to form the secondary data within the literature review. This proved a lengthy and difficult process, with an element of leeway that allowed for more aged sources. The author also discovered that more recent literature was obtainable by widening the global search criteria, so this was utilised. Furthermore, acquiring reasonable data collection for the questionnaires proved a difficult process with a limited amount. This is due to the specialist sector ADR falls into and the accessibility to participants with the desired skills and knowledge required to fulfil the needs of the aims and objectives.

Furthermore, some of the questions had limited options for participants in the survey, for instance, questions 3, 6, and 9. An open-ended provides an opportunity for participants to provide more insights. Therefore, this could have potentially affected the results of the study. In addition, at least three interviews were planned, but the emergence of Coronavirus and its prevalence in the UK restricted the study to only two interviews. Therefore, this could have affected the findings of the study. Including more interviewees in the analysis may have improved the study, which is an implication for future research.

Contingency Plans

Case studies will be utilised if issues arise, such as gaining insufficient data from the questionnaires. If data collected from the interviews are deemed inadequate, further interviews with the author’s LinkedIn connections will be requested.

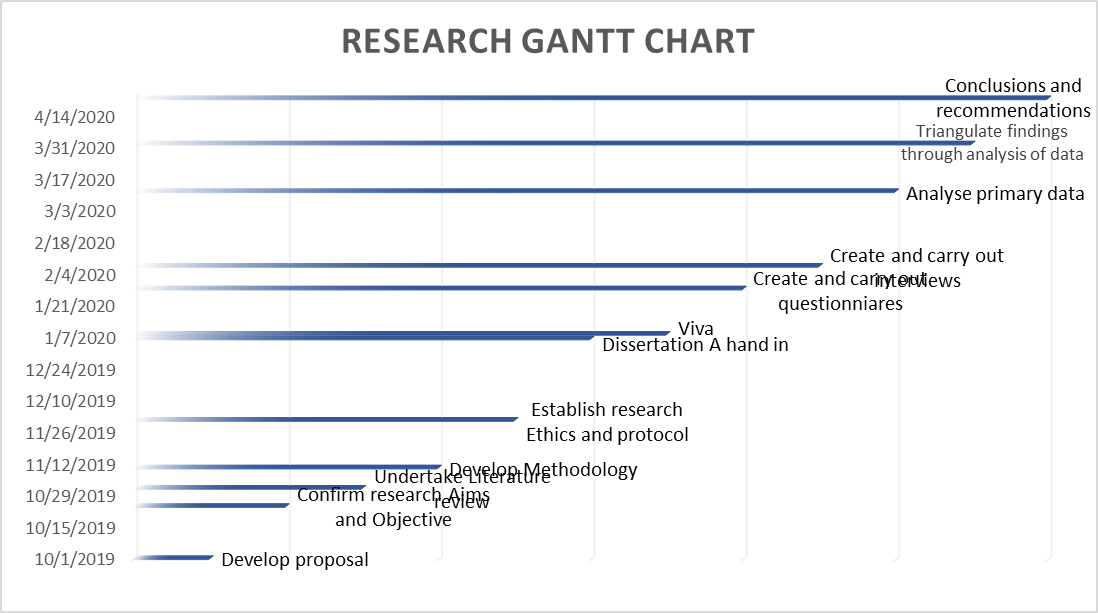

Research Gantt Chart

Ethical Considerations

The authors have always carried themselves professionally throughout the thesis by maintaining quality and integrity standards. They have ensured confidentiality and anonymity as their main priority and incorporated mechanisms to avoid harming participants whilst conforming with the appropriate ethical standards.

Participants have been informed of the research method and the potential outcomes. Any participant will not be aware of the other participants, and interviews will be conducted over the telephone. All collected data will conform with EU General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and be stored safely on university servers. All data will be kept until marking has been completed. Once this is done, the data will be deleted unless otherwise stated.

Due to the nature of data collection, minimal risks were present. Therefore, a risk assessment was not required. Instead, consideration of any activity that may have caused an unreasonable risk was accounted for.

Literature Review

Construction disputes arise due to disagreements among contract parties, and it is posited that conflicting opinions among project participants inevitably lead to disputes if not effectively managed (Alaloul, Tayeh, & Hasaniyah, 2019). The author suggests that the increasing complexity of construction projects and contracts heightens the likelihood of disputes, making them nearly unavoidable.

Eilenberg (2003) categorizes disputes into various levels, starting with disagreements at the lowest level and escalating to arguments. Although Eilenberg does not explicitly address the distinction between conflict and dispute, Fenn, Lowe & Speck (1997) propose that conflict could represent the initial stage of a dispute within a construction contract. Consequently, if conflicts are not promptly addressed, they may escalate into full-fledged disputes.

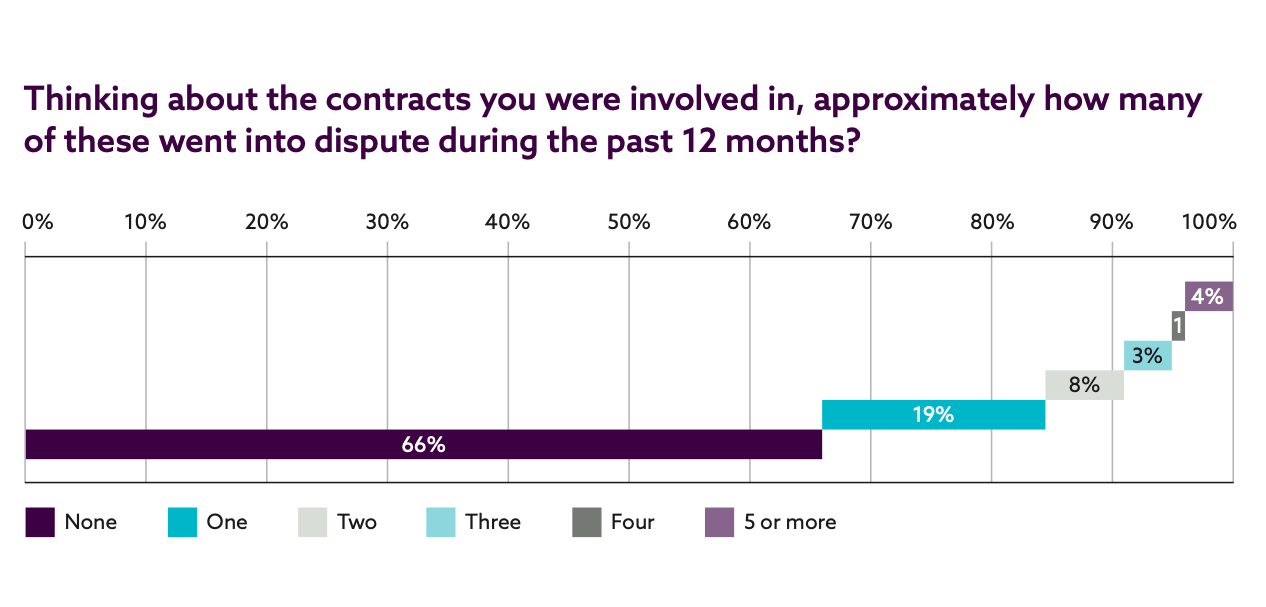

Supporting this notion, the National Construction Contracts and Law Survey 2018 findings reveal that, over 12 months between 2017 and 2018, 19% of contracts experienced at least one dispute, with 4% encountering four or more disputes. This underscores the continued prevalence of disputes in the construction sector (Malleson, 2018).

Contracts in dispute accessed on 15/11/19(Malleson, 2018)

Global Construction Disputes Report 2019 defines a dispute where two parties are in a situation where both differ in opinions of a contractual right, resulting in a decision being made under the terms of the contract, which transitions into a formal dispute (Arcadis, 2019). Alazemi& Mohiuddin (2019) and Aryal & Dahal (2018) agree the construction process makes conflicts unavoidable, especially due to the nature of the industry, which creates uncertainty. However, Netscher (2015) argues that 99% of construction claims can be settled without going down the dispute resolution process, minimizing the occurrence of disputes.

Causes of Disputes in Construction

This chapter evaluates the causes of disputes in construction specified by other researchers. When a dispute arises, the causes must be identified for a suitable resolution for all parties involved.

Disputes

Inevitably, conflict and disputes are natural and real in every project (Opata, Owuss, Oduro-Apeatu, & Tettey-Wayo, 2015). They may become apparent for several reasons and can be categorised into 3 main groups(Jaffar, Tharim, & Shuib, 2011).

- Organisational: Increased project complexity has led to ambiguity, which expresses uncertainty, and misunderstandings occur, giving rise to conflicting situations(San Cristóba, Carral, Diaz, Fraguela, & Iglesias, 2018).

- Contractual: Increased contractual complexity is inherent within the construction. It can increase the incidence of disputes occurring, such as a claim for an EOT, liquidated ascertained damages(LADs), loss and expense (L&E), payment, etc. (Sinha & Wayal, 2013).

- Technical: Errors/incomplete technical details, overdesign, etc. (Jaffar, Tharim, & Shuib, 2011).

Despite the categorisation of disputes, they can occur at any time during the process, even before any design work is carried out. Disputes can surface for many reasons, from as early as the initial stage of a project when it is first being discussed. The construction industry and its processes are niches compared to many other industries, creating unpredictability and risks that are sure to happen.

Mason (2016) suggests disputes follow the boom and bust cycle. As profit margins decrease, many people compete for smaller amounts of work. Arguably, many disputes have their seeds sown at the project's planning stage to hurry the commencement of construction, putting pressure on the consultants(Ekhator, 2016). Ekhator(2016)also states the agreement between client and contractor contains contractual obligations for both parties; however, these are sometimes not well-defined, presenting differing interpretations, often leading to disputes.

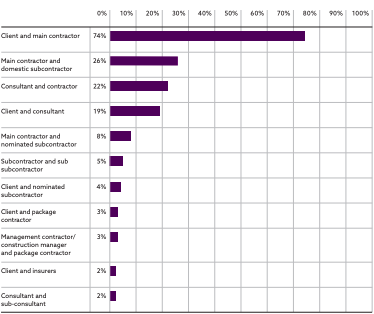

These claims support the literature in Figure 7 from the NCCLS 2018, where client and contract and client and consultant make up many parties in dispute. In support of this literature, a study by Kumaraswamy &Yogeswaran(1998) identifies the common causes of disputes are mainly related to contractual matters, such as variations, EOT, complying with payment provisions, accessibility of information, administration, management and unreasonable expectations of the client. In further research, Harmon(2003)emphasized conflicts may develop due to the limitations of available resources such as labour, materials and equipment, limited time, money, etc.

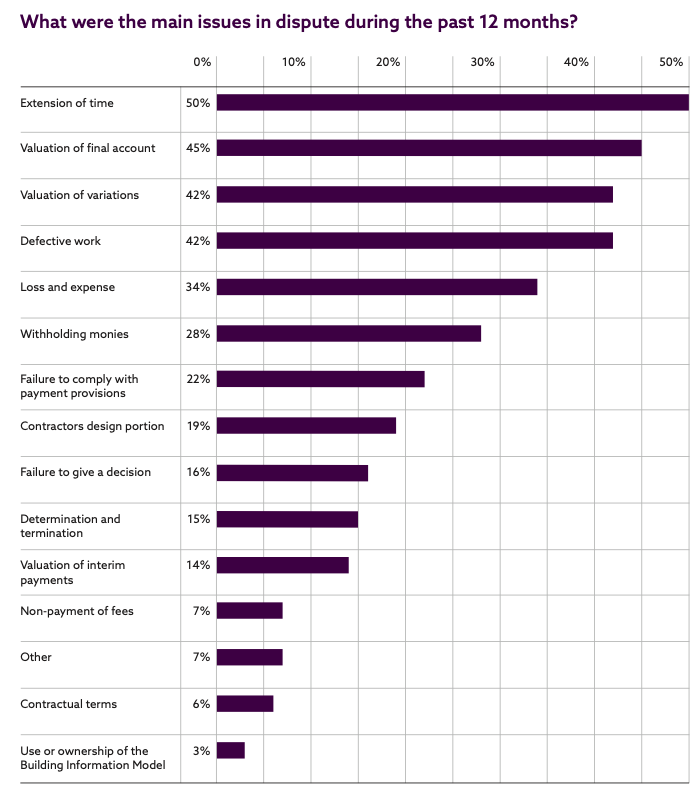

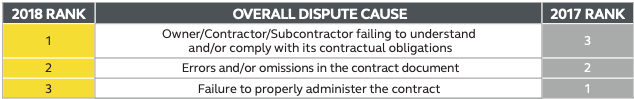

This can be linked to today's world, with the causes of dispute not differing but growing throughout the revolution and the ever-increasing complexity of the construction industry. The GCDR 2019 findings indicate that parties fail to understand and comply with contractual obligations as the number one cause of dispute(Arcadis, 2019). However, according to Malleson(2018), the most common reason for disputes is EOT, followed by final account valuations and variations. Figure 5 supports Malleson's suggestions, and Figure 6 supports Arcadis's suggestions.

Main issues in dispute accessed on 15/11/19 (Malleson, 2018)

The number one cause of the dispute was accessed on 15/11/19(Arcadis, 2019)

It can be deciphered from the literature that there is a common link to disputes arising, such as an EOT and contractual obligations that can be closely linked. The reason is contractual obligations are complex, and not all parties fully understand the clauses and how to abide by them, thus creating an idyllic opportunity for disputes to arise.

Common Parties in Dispute

Sakal(2004)states the construction industry today is different. From the 1980s and beyond, there was a shift from public financing by the central and local government, which prompted the industry to become more reliant on profit-oriented development. Consequently, relationships and trust between clients, contractors, and subcontractors withered and were replaced with distrust and conflict.

Arguably, this has impacted the relationship between the client, main contractors and subcontractors, thereby increasing the incidence of disputes, which can be supported by Malleson's (2018) findings in Figure 7, which identifies that 74% of disputes are between the client and main contractor and 26% between the main contractor and subcontractor. Kennedy, Milligan, Cattanach & McCluskey (2010) argue this is the reverse situation, as the most common parties in dispute remain the main contractor and subcontractor. However, the client and main contractor account for a significant portion.

Common parties in Dispute accessed on 15/11/19 (Malleson, 2018)

Main Causes for Disputes

The primary causes for disputes in various industries often revolve around financial disagreements, such as payment and budgetary issues. Additionally, conflicts frequently arise due to delays in project timelines, unexpected changes in project scope, and differing interpretations of contractual terms.

Extension of Time

Raj (2009)supports previous literature by stating that EOT claims are one of the most common and can only arise from a critical delay affecting contract completion. However, Alnaas, Khalil and Nassar(2014) argue that any delay to the progression of the contractors for reasons consequential to the client may argue they're entitled to an EOT even if this doesn’t delay the contract completion. Construction contracts generally allow the contract period to be extended if a delay occurs that is not the contractor's fault. The purpose of an EOT is to relieve the contractor of liability from such things as LADs for any time before the extended completion date (Rosenburg et al., 2017)(Keane & Caletka, 2015).

Furthermore, the benefit of an EOT for the employer is that it establishes a new contract completion date, preventing work completion time from becoming at large’(Klee, 2018, p. 299). The authors agree that an EOT is a provision in a contract whereby the contractor may request an extension to the original completion date should the client be responsible for the delay(Linnett, De Moraes, Lowsley, & Smith, 2015)(Eggleston, 2009). An EOT benefits the employer and the contractor (Linnett, De Moraes, Lowsley, & Smith, 2015). However, Eggleston (2009) contradicts this, stating that people within the industry use EOT claims to increase profitability via further loss and expense claims, which is also supported in Figure 5.

Final Account Valuations

A final account is an agreed statement for the amount paid to the contractor by the employer at the end of the contract. This is supported by Garner (2015), who states that a final account valuation is a conclusion of the contract sum that signifies the agreed amount of money the employer will pay the contractor. Furthermore, the final account typically includes any loss and expense associated with any EOT and any other claims, and it’s also an indication of the finalisation of disputes between parties(Garner, 2015).

Many people find having a single dispute at the end of the final account makes sense rather than having a series of ongoing adjudications throughout the project lifecycle (Contract Dispute Resolution Ltd, n.d.). In support of this, parties prefer resolving disputes that arise contemporaneously during a project to split disputes into more manageable sizes(Bell, 2019).

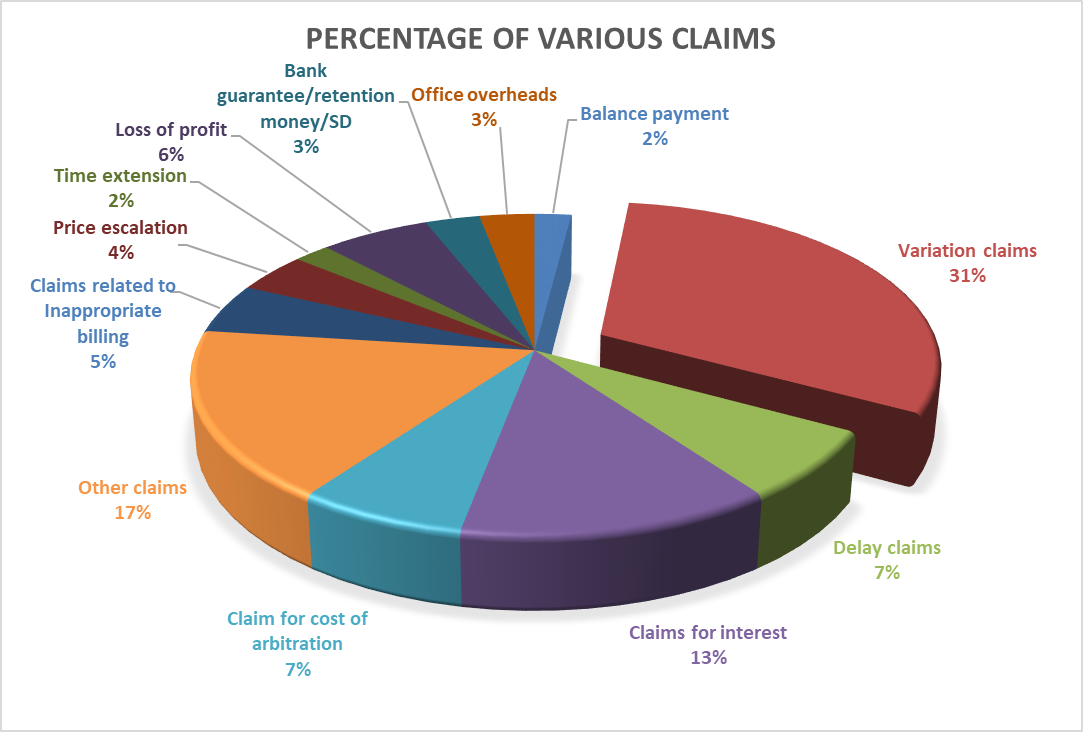

variation of percentage

variation of percentage

Valuation of Variations

Variations are works that are not included in the original contract and contracted price(Iyer, Chaphalkar, & Patil, 2018). The valuation of variations may consist of expenses other than work described in the variation instruction. It is not uncommon that disputes often relate to contract variations, especially the method by which the variation is valued. Disagreements occur for such things as the value of the variation being greater than the perceived value returned. This, in turn, leads to disputes. Rules were incorporated into the standard form of contract for valuing additional work. However, disputes still arise about which valuation rule applies and how it is interpreted(Carolan, 2017).

Valuation of variations is amongst the most common causes of disputes arising, which the CCLS2018 supports in Figure 5, and according to Sutrisna, Proverbs, Potts, &Buckley (2004), this has long been recognised as one of the most common causes of disputes. Further evidence is included in the pie chart below to support these statements. Out of a total of 821 claims, 254 of these were raised due to variations. These variation claims can be due to a change in specifications or quantity (Iyer, Chaphalkar, & Patil, 2018).

Contractual Noncompliance and Errors/Omissions in Contract Administration

For this research, all three causes are grouped as all contractual related and appear to be the main cause of dispute. Aryal & Dahal (2018) state that the number one cause of dispute during 2016 was poor contract administration and failure to understand and comply with contractual obligations, which has continued throughout recent years. Figure 6GCDR2019 above states that these are still the main causes. Anand (2017) supports these claims, stating that disputes are mainly related to disagreements on the contract's terms and conditions or misunderstandings of the contractual obligations.

A study by Hasheminasab, Mortaheb & Fardini (2014)delves deeper into the root causes of this ongoing problem related to contractual obligations. It states the contractor’s attitude towards risk sharing is an unfair and inaccurate evaluation of contractors, leading to failure to perform their obligations. Some problems associated with contract administration are outlined by Sebastian & Davison (2011), who acknowledged that ambiguous specifications, scope change, delay of the completion date, behavioural issues, and external factors are only a few of a diverse range of causes.

Kitt (2015) states that early recognition is essential to reduce disputes arising from poor contract administration. Sebastian & Davison (2011) argue that going beyond identification is key to determining why these occur and using an organizational behavioural problem-solving model to identify the root causes of the risks.

Anand (2017) argues that to avoid disputes concerning contract administration, the Project Manager, contract engineer or quantity surveyor must be put in place to help improve the cordial relationship with the client and eliminate pre-contract risks. Delving deeper, Anand (2017)states subcontractors are not reading and understanding all clauses/terminologies and use external assistance to aid in the legal jargon.

Brief History of ADR

Between 1993 and 1994, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) gained prominence and attention, largely attributed to a formal review by Sir Michael Latham, former construction minister and Member of Parliament for the Conservatives. Latham's announcement in 1994 emphasized the need for a less adversarial approach within the construction industry. He argued that to bring about change in the industry's dynamics, it was essential to examine the relationships between contractors and subcontractors. Latham stressed the importance of fostering positive working relationships between these key parties, recognizing their crucial role in successfully delivering projects. He underscored that disputes would persist unless mutual trust was established (Latham, 1994).

Latham's perspective extended beyond the UK, suggesting that the construction industry worldwide could benefit from adopting practices similar to those in the United States, where ADR was employed to prevent disputes from escalating into litigation. The review led by Latham became a significant and enduring topic of discussion, echoing similar reviews conducted in the 1950s through the 1970s. Subsequently, the Conservative Government Act of 1996 embraced the recommendations outlined in the Latham report, implementing legislative changes through The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (HGCRA) (Davies, Fenn, & O'Shea, 1998).

A historical examination of ADR by Barrett & Barrett (2004) defined it as an alternative to court-based problem-solving methods, revealing that its roots extend far back in human history, playing a pivotal role in various cultures worldwide. Additional research, such as that by Sanchez (1996), pointed out that the Anglo-Saxons employed dispute resolution procedures resembling modern methods like adjudication, arbitration, mediation, and negotiation. These mechanisms were available to defendants during legal proceedings.

Methods of ADR

Methods of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) encompass diverse approaches such as mediation, where a neutral third party facilitates discussions; arbitration, involving a binding decision by an arbitrator; and negotiation, allowing parties to reach a voluntary settlement outside the courtroom. These methods offer flexible alternatives to traditional litigation, promoting efficient and collaborative resolution of conflicts.

Negotiation

Negotiation is the most common alternative dispute resolution (ADR), normally the first step to resolve a conflict. This is supported by The Construction Index (2019) & She (2010), who state that negotiation remains the preferred resolution method. These claims are supported by the Arcadis GCDR 2019, where negotiation ranked number one overall for the most common method utilised for dispute resolution:

Most popular methods for resolving disputes Accessed on 17/11/19 (Arcadis, 2019)

This form of ADR requires all parties to provide documentation to support their claims to reach an equitable settlement of their assertions(Yates, 2011). It is the most cost-effective method and sometimes the most proficient. Negotiation can be divided into two separate categories: competitive and collaborative. Collaborative negotiation focuses on creating a ‘win-win’ scenario where all parties involved get part or all of what they were looking for. This approach produces the best results in building long-term relationships and minimising conflicts(APM, 2019).

This method has advantages in terms of cost and time as it provides quick turnaround inexpensively, offering full control of the process and its outcome due to an in-house procedure. Dispute Prevention and Resolution Services (2017)reports on disadvantages associated with negotiation and includes no guarantee of resolution and no legal precedence. It can also be used as a stalling tactic to prevent other parties from asserting their legal rights. Santiago (2019)supports this, suggesting that enforcing decisions may be difficult because decisions depend on the parties' goodwill, and poor negotiation skills may lead to a stalemate.

Mediation

A study by Gould (2010)looked into the use of mediation in UK construction disputes concentrating on parties at the Technology and Construction Court (TCC) in London, Birmingham and Bristol. These participants were interviewed on how they settled their disputes and their mediation experiences during litigation. The results showed that 35% of the cases settled after commencing litigation in the TCC used mediation.

The survey also looked at cost savings attributable to settled mediations, which were colossal, and successful mediation was settled within the stipulated litigation time scales (Gould, 2010). Gregory-Stevens, Frame & Henjewele (2016) support this by suggesting mediation has advantages, enabling disputes to be resolved at reduced cost and providing greater satisfaction to all parties than litigation. Furthermore, research by Byrne (2016) states mediation is non-binding, eliminating the judge's decision and giving you greater control over the outcome.

In contrast, Bennett (2018) states that no legal professional to enforce legal proceedings could lead to the procedure's exploitation. In addition, both parties must fully commit to the procedure and choose a mediator to prevent any prejudice to either side. This can prove to be a difficult task as the parties are already in disagreement. Trussell, Clark & Agapiou (2016) counter it by stating that despite Bennett's (2018) opinions, parties must compromise their positions to settle. This requires full discovery, which results in a negative impact on time and costs. At the same time, mediation focuses on making deals and overlooks the right and wrongs, supporting earlier literature on the exploitation of the procedure.

Furthermore, Bennett (2018)says the choice of the mediator can have a crucial effect on how the mediation is carried out, and a good mediator cannot be successful when the parties truly do not wish to settle. However, in contrast, a bad mediator may hinder a successful settlement when the parties wish to settle.

Adjudication

Adjudication can be defined as an interim dispute resolution process where all parties submit their dispute to an independent third party for a decision(Pickavance, 2016). Gaitskell (2007) states adjudication is the most important alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process in the UK and Commonwealth countries. In contrast, Bailey (2014) argues that arbitration was and had been the dominant form of ADR in construction contracts for some time.

Sakate& Dhawale (2017) state the adjudicator is a neutral individual who is not involved in the day-to-day running of the contract and often has no meeting with the adjudicator. Thwaites(2016) expands on this by stating this endeavour's drawbacks, such as being unable to cross-examine. This has been recognised by the courts, which have clarified that they will enforce the adjudicator's decision even if it is wrong based on the facts or the law.

The main advantages associated with adjudication are time and cost. Perrin (2014) states that its strength lies in its potential to save money and keep the project on track, which other forms of ADR may have derailed. Speed is an advantage of adjudication over other methods, such as arbitration or litigation. The decision is made within 28 days of service of the referral document, which is extremely fast compared to litigation(Thwaites, 2016).

Furthermore, regardless of the outcome, both parties must bear their costs, and although this is expensive to themselves, it is over a short period compared to litigation. If unsuccessful, they don’t risk paying the other parties' costs. In contrast, although this is a speedy process, this means the process is inherently “rough and ready”, thus meaning there is not enough time in the adjudication process for any detailed and careful analysis of the facts and issues of the dispute(Thwaites, 2016).

Arbitration

Before introducing other forms of ADR, arbitration and litigation were the main methods of resolving disputes. Some industry professionals feel it is the most effective way of resolving disputes. It is perhaps the oldest form of ADR and is used widely in construction disputes. To define this method of ADR, Mason(2016) states arbitration is an alternative to litigation whereby parties refer to an existing or future dispute to the determination of one or more independent persons acting judicially.

In this method, the arbitrator expresses the decision in an award, which becomes legally binding and enforceable in a court of law. Arbitration is similar to litigation in many ways and has been described as ‘litigation in suits rather than wigs’. Both arbitration and litigation are intended to be final and require both parties to prepare statements of their cases similar to litigation(Mason, 2016). However, a study by Khekale & Futane (2015)argues that many dissimilarities between arbitration and litigation can be deciphered. No dispute commented that there is little procedural difference between the two processes.

Traditional Method of Dispute Resolution

Traditional dispute resolution methods often involve formal court proceedings, where legal professionals present cases before a judge or jury. These adversarial processes rely on legal rules and judgments to resolve conflicts, contrasting with the more collaborative and flexible nature of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods.

Litigation

Even though alternative dispute resolution (ADR) can be utilised, court proceedings are still one of the most common forms of resolving disputes(Cook, 2016). Litigation cases are referred to the Technology and Construction Court (TCC), a specialist court governed by the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) and TCC guide. The advantage of Litigation is that a judge will manage the claim process throughout the court proceedings. Complex issues can be dealt with, and the parties obtain a binding and enforceable decision.

Khekale & Futane (2015) state that the rising cost, delay, and risk of the litigation process have prompted the industry to look for new and more efficient ways. Gaitskell (2005) supports this statement by expressing that most disputes are multi-party affairs with many solicitors and counsel, meaning a lengthy and expensive process. Consequently, because of the CPR, litigants must undergo several procedures and incur substantial costs before proceeding.

There is still a place for litigation within dispute resolution despite being used less frequently due to the courts referring cases to ADR under the CPR. Litigation can be seen as a vital support role and a last resort when dealing with cases where ADR has failed (Wood et al., 2017). Khekale & Futane (2015) counter this by stating that despite Wood et al.'s (2017)opinions, litigation is not as efficient in terms of cost and time. However, Vos (2019) argues that not enough has been done and that the courts must implement intelligent technology reform in our current system.

Conclusion

To summarise, the construction industry is a very complex and challenging environment, and with this comes conflicts, which are of great concern to the industry. To manage this effectively, the claims management process must ensure that every party involved handles claims arising fairly. The literature review covers the main causes of disputes in the built environment and the dispute resolution methods to resolve these claims.

Interview Analysis

This chapter's primary aim is to investigate the effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in construction. For this purpose, professionals with ample industrial experience have conducted interviews directly involved in the dispute resolution process. Meanwhile, to analyse the data, thematic and statistical analysis have been used to shed light on the extent to which the study's primary question is being addressed and test the hypothesis. Lastly, the discussion has also been conducted to evaluate the extent to which the objective of the overall study is achieved.

Participant Code | Category | Job Role | Date |

P1 | Affiliate Company | Quantum Expert | 17/02/2020 |

P2 | Legal Solution on Live Projects-Third part representative | Chartered Surveyor | 20/02/2020 |

Interviewee Profile

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the above participants, who had a minimum of 10 years of experience within ADR. The minimum sample size for interviews was two, which was achieved. Furthermore, the transcripts obtained were of a greater scale than normal, and the interviewees targeted were specialists within the ADR sector, ultimately providing a richer insight.

Thematic analysis is the most widely used qualitative data analysis method that emphasizes identifying, analysing and interpreting patterns present in the data. It has been stated that interview transcripts contain similar trends identified and analysed to address the research questions and can also be used to develop a theoretical framework(Braun, 2014). Meanwhile, it is also a more flexible method for analysing qualitative data since the researcher can identify the factors present in the data based on which themes are constructed, and transcripts comprising common answers are analysed and discussed under each identified theme. Similarly, interviewees are referred to as P1 and P2, and the line number of each transcript references a statement from the transcript.

Most Common Causes of Disputes Between Clients and Contractors

Disputes between clients and contractors commonly stem from unclear project specifications, timeline misunderstandings, scope changes, project delays, and payment disagreements. Clear communication and well-documented contracts are essential to prevent and address these challenges in construction projects.

Extension of Time

Disputes are contradictions or disagreements between two parties over a matter, project, or event. The most common disputes being highlighted by P1 (66-69) are that EOT is a major issue, and P2 (82-87) states that time and budget constraints are issues affecting parties resulting in disputes. The conflict remains an EOT because when a party asks for this, it must be granted at the time of the event, as highlighted by P1 (60-61). P2 (106-108) supports this, stating that EOTs are quite subjective, which can be conflicting, meaning clients struggle to understand why more time is needed. In this regard, Alnaas, Khalil and Nassar(2014)and Keane &Caletka(2015)state contractors also ask for EOT due to reasons consequential to the client. However, they still claim EOT even when the project will not be delayed, and the core reason is to get relief from any liabilities due to any delay in time.

Hence, they already claim EOT. Meanwhile, P1(66-69) also stated that clients do not know how to claim EOTs, leading to ignorance towards their responsibilities and causing further conflict when trying to claim this time back. This can be correlated to not understanding the contract obligations. Although P1 and P2 have similar views on EOTs, P2 (92-94) suggested they do not have many conflicts about EOTs as they fall away quickly but more about the monetary side of things, which can be interpreted as differing opinions. (McCall, 2017)

Final Account Variation

P2 (228) (117-123) states you now have full-blown final accounts full of EOTs for reasons such as subcontractors not performing and affecting the client and main contractor. This is supported by P1 (102-104), stating frequent changes and many variations are major reasons why disputes arise over the project. Issues and conflicts are inevitable given the industry involves various parties in one project, and their work is interdependent. Furthermore, another issue highlighted by P2(88-89) is that there is a 99.9% chance of change or variation because the contract allows for it, and the emergence of conflict depends on how well parties trust one another. Therefore, final account variations are highly expected but may not always lead to conflict.

Valuation of Variation

P1 (105-108) states project change and inability to agree, even if viable, is the main cause for dispute. P2 (89-90) states clients do not mind paying for change if it is not too much, implying that the variation will likely be rejected if the valuation is too costly. It has also been discussed that variations are inevitable and are certain to occur irrespective of the proper contract implementation. While all variations do not lead to conflict, developers, commercial entities, offices, or businesses may lead to conflict since variations tend to require more time and costs. The other party may not agree on the valuation of variations due to their reasons as they consider the time as money, as reported by P2 (95-97). Hence, the parties may conflict with the overvaluation of variation outside of the contract, causing conflict. As per Carolan (2017), the rules of valuation and how they are interpreted create conflicts between the parties.

Non-compliance with Contractual Obligations

P1(56-57) (61-63)(81-84) suggests the provisions for EOTs are not very good, and both client and contractor do not adhere to these. They say companies have not been applying for EOTs properly, and even senior staff do not fully understand the obligations associated with the contract.

Similarly, Anand (2017) states in the literature that subcontractors are not reading and understanding the clauses and terminologies, and P2 (326-330)(343-346) supports these comments, stating neither party has a clue when it comes to an understanding the contractual obligations because they do not even read the contract.P2 (124-134)(378-384)states contractors sometimes suddenly say we cannot do the work in the remaining period, or other parties not performing then the whole project suffers leading to further claims such as EOTs. The responses of P1 and P2 imply a lack of compliance with contractual obligations. This can lead to further claims, such as EOTs, linked to other common causes, such as final account variation and valuation disputes.

ADR vs Traditional Method

ADR, such as mediation or arbitration, emphasizes collaborative resolution outside the courtroom, offering flexibility and quicker outcomes compared to the traditional method, which involves formal court proceedings, often characterized by adversarial processes and longer timelines. The choice between ADR and traditional methods depends on the nature of the dispute and the parties' preference for a more cooperative or confrontational approach.

Preference

Interviewees were asked about their thoughts on alternative dispute resolution (ADR) compared to traditional methods for handling disputes. Interviewee P1 (99-101) (120-121) stated ADR is mainly preferred due to time-related constraints and has been preferred since the late 90s since the process of courts is long and in construction, time is money. Similarly, Jaffar, Tharim&Shuib(2011) state that irrespective of the source of the dispute and the issue's relation, evolution is key since time is money (McCall, 2017). P2 (197-199) supports this, stating litigation is incredibly expensive and slow and has always been this way. The response indicates that ADR is preferred over legal proceedings for settling disputes.

P1(154-155) states they were not in the industry before ADR and now make a living from this, so it could be interpreted as potential bias over the preference of ADR instead of litigation. However, interviewees insist on using ADR as it is effective for all parties regarding conditions, situations, and frequency of disputes. P2(207-211) (285-287) supports the claim that parties prefer ADR as court proceedings were being used to send companies that could work in the plaintiff’s favour as they would not have to pay anybody. Also, the process is more efficient since ADR involves solicitors, arbitrators and third parties to resolve disputes.

Therefore, the UK government suggests ADR through third-party involvement before engaging in court proceedings. This is because most issues are resolved with ADR with a high success rate(GOV.UK, 2015). It is determined the respondents have commonly preferred ADR to traditional methods, given each party would lose a great amount of time and cost to approach a resolution.

Negotiation

P1 (180) states the quickest way to resolve a dispute is by negotiation because it offers a quick way to resolve the dispute in which two parties are face to face and put all their issues together to approach a potential solution. Similarly, P1(256-259) further highlighted in their experience that negotiations favoured methods to resolve issues when they arise. In this regard, the Construction Index (2019) and She (2010) have stated that negotiations remain the most favourite because they are the first step towards resolving a conflict. Meanwhile, negotiations can take form collaborative and competitive, where most of the time, a collaborative approach is undertaken, leading to a win-win scenario for all involved in the conflict(APM, 2019).

Mediation

Concerning mediation, P2(160-163)states that in this process, they remain the third party and start communication between them. The respondent also highlighted that communication is the issue which creates a problem, and mediation is the process in which communication is the only way to resolve the dispute. Furthermore, P2(299-304) states that mediation works well within commercial disputes between the parties; the mediation process starts when parties contact each other to resolve the issue. Therefore, it is determined that the parties prefer mediation when negotiations do not work.

In contrast, the basic difference between mediation and negotiations is that negotiations do not have a third party or mediator. Still, a third person leads the parties in the mediation process and tries to resolve the issue. Meanwhile, due to the time constraints and costs associated with the other legal procedures, these ADR methods are preferred as this is supported by P2 (448) (454-456), stating mediation is the quickest method.

Adjudication

P1(123) states adjudication is cheaper and quicker when parties do not want to be involved in a litigation process; as per the literature, adjudication is when all parties submit their arguments, and a third party decides. Similarly, P1(273-276) states that adjudication is much quicker and can give a decision within 28 days, and P2 (218-220) (233)supports this, stating it is considered quick and dirty because the decision could be against of the party. Each party must follow the decision, which must be done in 28 days. However, P1(324-326) states an adjudication can take 46 days to resolve the conflict. As per the pace of work in the construction industry, this can be costly to both parties in terms of losses because each party's work would probably be halted for the period.

Arbitration

P2(404) states that the arbitration process is very slow and as expensive as courts; hence, resolving the conflict between the parties could take a lot of time. In support of this, P1 (121-122)states that arbitration was mainly used at the beginning of ADR. However, due to the HGCRA, everyone moved towards adjudication as it was cheaper and quicker. Furthermore, P1 (191-194) (315-316) states you can spend months, even years, on arbitration costing hundreds of thousands, and then it still gets to litigation, which is like a double down on time and cost. Also, Mason(2016) states that arbitration is similar to litigation, supported by P1 (319-320), stating a tribunal they were part of was effectively an arbitration. Therefore, it is evident that despite being part of alternative dispute resolution (ADR), it is not as effective and efficient as other methods of ADR.

Effectiveness of ADR in Terms of Cost and Time

ADR is often more cost-effective and time-efficient than traditional litigation, as it minimizes court-related expenses and accelerates dispute resolution through mediation or arbitration, providing a quicker and more economical path to resolution for parties involved.

Positivity

The effectiveness of ADR has been discussed by interviewee P1 (155-156) (228-229)(181-182), stating that it has to be a positive, certainly the theory of it and that ADRemerges as the most appropriate method to resolve the conflict since itis much faster and cheaper than litigation.P2 (397) (407-408) supports this by stating that ADR has a million good reasons of being incorporated into the standard form of contract and a benefit is it is confidential, and you have some form of experts. The responses imply that two parties can significantly save their company reputation, time and costs associated with the legal process. Also, parties involved would not normally agree to court since ADR is considered more effective than litigation, saving time, cost, and the project.

In addition, UK courts and guidelines suggest that pre-action conducts and protocols in para 8-11 litigation should be the last option for parties and consider different forms of ADR that could enable parties to approach consensus before initiating legal proceedings. Meanwhile, para 9 further emphasizes settlement being engaged in legal proceedings (Justice GOV UK, 2020). Therefore, it is determined that the positivity of ADR always remains for the parties; even the legal department suggests engaging in ADR before and even after proceedings to settle. In this regard, P2(281-282) (292-293)(272-273) supports ADR, stating it’s a major positive due to its effectiveness, implying the industry wouldn’t use it otherwise and claiming that ADR is positive when comparing this to litigation.

Negativity

Similarly, P1 (266-269)ADR stated that each party might not be happy with negotiations but willing to accept them since no party wants further delays that would have inevitable negative consequences regarding monetary losses. Also, when parties engage in a dispute, it tends to affect their relations to some extent but not always, as reported by P1 (207-211), stating any parties go against each other to resolve conflicts and then work with each other again on the next project. Furthermore, arbitration is said to be equal to litigation in terms of time and costs.P1 (377-380) states when costs soar, litigation is essential; otherwise, parties will suffer colossal losses. Therefore, it is going to be a costly settlement either way.

Reliance

The interviewees' responses indicate that negotiations are the best way to resolve the issue and are only possible in pre-trial conditions. Hence, ADR is a much quicker and cheaper process than litigation in the industry; it is also stated that in the process of adjudication, the decision may be obtained within 28 days, but if the litigation process is followed, that would take months and would probably be a costly decision for each of the party. This decision may also be against any parties, creating relations complications. Therefore, both parties will suffer irrespective of a favourable decision in either condition. Thus, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is the most effective way to sort out the problems through mediation, considering the consequences of delay, and it would also maintain the best relationship between the parties. P1(125-131) supports these claims by stating the industry relies on ADR rather than litigation, as it’s looked upon unfavourably to go to litigation if you haven’t tried ADR first.

Questionnaire Analysis

A pilot questionnaire confirmed the questions to be coherent and take around 6 minutes to complete. Following this, construction professionals with diverse experiences and job titles were approached mainly via the author's LinkedIn account. 71 people were contacted mainly by direct message via LinkedIn but also via email, and 244 people view

13.3%.

Respondent’s Experience

Approximately how long have you or your organization been using ADR services? | ||

| Frequency | Per cent |

More than 5 years | 37 | 88.1 |

3-5 years | 3 | 7.1 |

1-2 years | 1 | 2.4 |

Less than one year | 1 | 2.4 |

Experience Level

Table 3 demonstrates the level of experience among the respondents of the survey, and findings show that the majority of the respondents consisted of 37 (88.1%) with experience over five years, and some other respondents also had experience levels ranging from one year to 5 years. The majority of the respondents were highly experienced in the construction industry. Hence, this has provided more appropriate responses reflecting the true conditions of the industry.

Question 2 - Role of Respondents

Role | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Contracts Manager | 3 | 7.1 |

Director | 13 | 31.0 |

Chartered Construction Manager | 1 | 2.4 |

Adjudicator/Arbitrator/Consultant | 6 | 14.3 |

Quantity Surveyor | 3 | 7.1 |

Claims Consultant | 3 | 7.1 |

Regional Director | 2 | 4.8 |

Planning Manager | 4 | 9.5 |

Commercial Manager | 1 | 2.4 |

Chief Executive Officer | 1 | 2.4 |

Others | 5 | 11.9 |

Table 4 - Role of Respondents

Table 4 demonstrates the roles of respondents included in the survey. It is determined that 13 (31%) respondents were directors of the companies involved in construction, followed by Adjudicator/Arbitrator/Consultant 6 (14.3%), and others included contract managers 3 (7.1%) and Planning Manager 4 (9.5%). Most respondents are from higher posts that are more effective and provide more valuable responses than those at lower levels.

Question 3

Thinking about the contracts you were involved in within the last 12 months, how many of these went into dispute? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

More than Six | 9 | 21.4 |

Five or more | 16 | 38.1 |

Three | 2 | 4.8 |

Two | 8 | 19.0 |

One | 7 | 16.7 |

Number of disputes in the last 12 months

Table 5 illustrates the number of disputes faced by the respondents in the last 12 months; it shows that 9 (21.4) respondents stated more than six, 7 (16.7%) stated one, 16 (38%) stated five or more, 8 (19%) stated as two. Lastly, 3 (4.8) respondents stated they encountered three cases last month. This implies that, on average, 8 disputes are encountered by respondents yearly.

Question 4

Who were these disputes between? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Client and main contractor | 1 | 2.4 |

Main contractor and subcontractor | 3 | 7.1 |

Consultant and contractor | 4 | 9.5 |

Subcontractor and subcontractor | 1 | 2.4 |

Client and main contractor, Main contractor and subcontractor | 1 | 2.4 |

Client and main contractor, Main contractor and subcontractor, Consultant and contractor, Subcontractor and subcontractor | 32 | 76.2 |

Relationship of Parties in Dispute

Table 6 illustrates the most common disputes between all parties involved, and there is no specific majority in which parties mostly come into dispute. This implies that a dispute can be between any party at any time, irrespective of the party itself and its role; when a party’s interest is compromised, this leads to a dispute. However, the table shows that 32 (76%) mutually stated that a dispute might occur between the client, the subcontractor, and everyone involved.

Question 5

Of these claims, what method of ADR was utilised to resolve the dispute? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Negotiation | 11 | 26.2 |

Adjudication | 2 | 4.8 |

Mediation | 4 | 9.5 |

Arbitration | 1 | 2.4 |

All | 24 | 57.1 |

Method of ADRutilised

Table 7 implies that most respondents used all these methods in resolution. Less serious disputes will likely be resolved through negotiation, mediation, or arbitration based on mutual respect and understanding. However, when these prove ineffective in handling the complex nature of the dispute, parties refer to adjudication for resolution. Therefore, it is determined that all methods of ADR are being used based on the complexity of the case and the type of party involved.

Question 6

In your most recent dispute, how long did the process take months? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

More than twenty | 4 | 9.5 |

Fifteen to twenty | 6 | 14.3 |

Ten to fifteen | 8 | 19.0 |

Five to ten | 4 | 9.5 |

One to five | 18 | 42.9 |

One or less | 2 | 4.8 |

Duration of dispute resolution

Table 8 illustrates the majority of respondents have stated that a dispute takes 1-5 months to resolve. It can be interpreted that resolution mainly depends on the complexity and matter of a dispute between the parties. Hence, common disputes like EOT and failing to comply or understand the contracts could be resolved sooner than others.

Question 7

What were the main issues in dispute during the past 12 months? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

EOT | 9 | 21.4 |

Final account valuation | 1 | 2.4 |

Valuation of variations | 1 | 2.4 |

Failing to understand & comply with contract obligations | 2 | 4.8 |

Loss and expense | 1 | 2.4 |

Failing to understand & comply with contract obligations, Errors and/or omissions in the contract document | 3 | 7.1 |

EOT, failing to understand & comply with contract obligations | 1 | 2.4 |

EOT, VOL | 2 | 4.8 |

EOT, L&E, FAV, VOV, FTU& comply with contract obligations | 2 | 4.8 |

EOT, L&E, FAV, VOV, FTU & comply with contract obligations, Errors and/or omissions in the contract document | 1 | 2.4 |

EOT, FAV, VOV | 2 | 4.8 |

EOT, L&E, VOV | 1 | 2.4 |

EOT, L&E, FAV, VOV | 1 | 2.4 |

EOT, L&E, Other | 1 | 2.4 |

EOT, FAV | 3 | 7.1 |

EOT, VOV, failing to understand & comply with contract obligations | 2 | 4.8 |

EOT, L&E | 2 | 4.8 |

EOT, L&E, FAV, VOV, Errors and omissions in the contract document | 3 | 7.1 |

Errors and/or omissions in the contract document | 1 | 2.4 |

L&E, VOV | 3 | 7.1 |

Main issues in dispute

Table 9 illustrates the number of disputes being highlighted by the respondents. Most respondents have included EOT as the most common dispute, followed by failure to comply with contractual obligations and loss and expense or valuation of variations. Meanwhile, if the table is compiled, 6 common disputes among the parties lead to disputes.

Question 8

What factors would influence your decision to choose a means of settling disputes? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Cost | 18 | 42.9 |

Time | 6 | 14.3 |

Cost, Time, Confidentiality, Relations and Complexity | 18 | 42.9 |

Factors influencing settling disputes

Table 10 illustrates the most common trend for settling disputes: cost, followed by time, supporting the consensus that time is construction money, which is also expressed by interviewee P2 (97). Therefore, it can be determined that cost and time influence decision factors. Still, some parties also consider confidentiality, business relations, and the complexity of a dispute when deciding how to resolve it.

Question 9

Do you think there are fewer or more advantages over disadvantages of using ADR services? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

More | 35 | 83.3 |

Equal | 4 | 9.5 |

Less | 2 | 4.8 |

Pros and cons of using ADR

Table 11 illustrates whether ADR has fewer or more advantages and disadvantages. The most common trend by a significant portion was 83.3% stated that there are more advantages than disadvantages. This implies that most professionals prefer utilizing the ADR service to resolve disputes.

Question 10

What would you consider to be the most effective method of dispute resolution? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Negotiation | 10 | 23.8 |

Adjudication | 2 | 4.8 |

Mediation | 1 | 2.4 |

Arbitration, Negotiation | 2 | 4.8 |

Arbitration, Adjudication, Mediation, Negotiation | 11 | 28.5 |

Mediation, Negotiation | 1 | 2.4 |

Arbitration, Adjudication | 13 | 31.0 |

Arbitration | 1 | 2.4 |

Preferred method of ADR

Table 12 illustrates the most common trend of 23.8% of participants who believe negotiation is the most effective. This is supported by interviewees P1 (256-257)and P2 (426-427), who state this is the best way to resolve disputes. On the other hand, 28.5% of participants stated all four types of methods are preferred. Still, as the literature supports, negotiations are normally the first step, and if this fails, then other methods are used which become the most effective.

Question 11

Do you think ADR has had a positive or negative impact on time? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Extremely negative | 1 | 2.4 |

Moderately negative | 2 | 4.8 |

Slightly negative | 1 | 2.4 |

Neither positive nor negative | 4 | 9.5 |

Slightly positive | 9 | 21.4 |

Moderately positive | 13 | 31.0 |

Extremely Positive | 11 | 26.2 |

ADR about the impact on time

Mean | 5.4634 |

Standard Deviation | 1.50163 |

Variance | 2.255 |

Question 11 Descriptive statistics

Table 13 illustrates a common trend of ADR having a 78.6% positive effect on time ranging from slightly to extremely, whilst 9.5% remained neutral, stating neither positive nor negative. On the other hand, 9.6% of respondents stated ADR hurts time from slightly to extremely. Furthermore, the mean response of 5.46 indicates that, on average, respondents stated ADR has a slightly positive impact on time. Still, this mean value could increase or decrease by a standard deviation of 1.50. Meanwhile, it can be stated that the majority agreed ADR has a positive effect on time, and the few who disagreed may have had a bad experience with ADR.

Figure 10 - Histogram of time |

Question 12

Do you think ADR has had a positive or negative impact on cost? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Extremely negative | 1 | 2.4 |

Moderately negative | 6 | 14.3 |

Slightly negative | 3 | 7.1 |

Neither positive nor negative | 6 | 14.3 |

Slightly positive | 8 | 19.0 |

Moderately positive | 8 | 19.0 |

Extremely Positive | 10 | 23.8 |

Table 15 – Impact has ADR on cost

Mean | 4.8571 |

Standard Deviation | 1.81553 |

Variance | 3.296 |

Question 12 Descriptive statistics

Table 15 illustrates the common trend of ADR having a 61.8% positive effect on cost ranging from slightly to extremely, whilst 21.3% of participants negated and stated it hurts costs, with 6 respondents stating ADR has a neutral effect on costs. Furthermore, the mean response of 4.85 implies that respondents have slightly agreed but have a mean of less than 5, suggesting that many participants did not agree with the statement. The standard deviation is also slightly higher, indicating higher fluctuations in responses and that many professionals did not agree with the statement and either remained neutral or gave a negative opinion. However, it can be claimed that the majority agreed ADR has a positive effect on cost given that it saves costs in two ways: one in terms of money and the second in terms of time is construction money.

Figure 11 - Histogram of cost |

Question 13

EOT is the number one cause of claims leading to alternative dispute resolution. Do you; | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Disagree | 6 | 14.3 |

Somewhat disagree | 7 | 16.7 |

Neither agree nor disagree | 6 | 14.3 |

Somewhat agree | 9 | 21.4 |

Agree | 9 | 21.4 |

Strongly agree | 4 | 9.5 |

Table 17 - EOT claims

Mean | 4.4878 |

Standard Deviation | 1.59878 |

Variance | 2.556 |

Question 13 Descriptive statistics

Table 17 illustrates the most common trend, 52.3% in agreement, ranging from somewhat to agree to strongly support literature (Raj, 2009). Meanwhile, 14.3% of respondents remained neutral, implying they may have encountered the same claims frequently. Furthermore, the mean response of 4.48 indicates, on average, the response was between somewhat agree and neither agree nor disagree. Therefore, it can be stated that those respondents have experienced frequent disputes other than EOT; hence, they somewhat agreed and remained neutral.

Figure 12 - Histogram on EOT |

Question 14

Do you think the ever-increasing complexity of construction contracts has led to more contract complications and disputes? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Probably not | 8 | 19.0 |

It might or might not | 4 | 9.5 |

Probably yes | 18 | 42.9 |

Definitely yes | 12 | 28.6 |

Complexity of contract leading to disputes

Mean | 3.8095 |

Standard Deviation | 1.06469 |

Variance | 1.134 |

Question 14 Descriptive statistics

Table 19 illustrates a common trend of a total of 71.5% stated probably to definitely yes to question 14, implying respondents agreed that the increasing complexity of contracts has led to more complications, thus leading to more disputes. In addition, the mean response to this question was 3.80, suggesting, on average, the responses fall within probably yes and might or might not; hence, it can be interpreted that a portion of the study did not agree, but some portion also agreed on this statement. Therefore, it is determined there may be certain projects in which disputes occur due to the complexities of the contract, but this is not the case. On the other hand, professionals had mixed opinions that emphasized remaining neutral on the statement. Thus, the mean response also fell within that category.

Histogramon complexity of contracts

Question 15

Do you think Litigation is the better or worse way of dealing with disputes than ADR? | ||

| Frequency | %age |

Much worse | 16 | 38.1 |

Moderately worse | 4 | 9.5 |

Slightly worse | 13 | 31.0 |

About the same | 3 | 7.1 |

Slightly better | 1 | 2.4 |

Moderately better | 3 | 7.1 |

Much better | 2 | 4.8 |

Litigation vs ADR

Mean | 2.6667 |

Standard Deviation | 1.77608 |

Variance | 3.154 |

Question 15 Descriptive statistics

Table 21 illustrates the most common trend recorded: respondents thought litigation was much worse than ADR at 38.1%. A further 31% stated slightly worse, meaning a total of 69.1% overall implied ADR is a better option in solving disputes. However, a total of 14.3% believed litigation to be better. Therefore, it can be said the majority agreed litigation is worse than ADR, suggesting it is not as effective or efficient. Furthermore, the mean response for this question was 2.66 with a standard deviation of 1.77, implying that, on average, respondents stated litigation is slight to moderately worse than ADR. This is because ADR is cheaper and quicker in getting a settlement. In contrast, litigation is considered the worst-case scenario since it takes longer and incurs more costs, increasing losses for both parties.

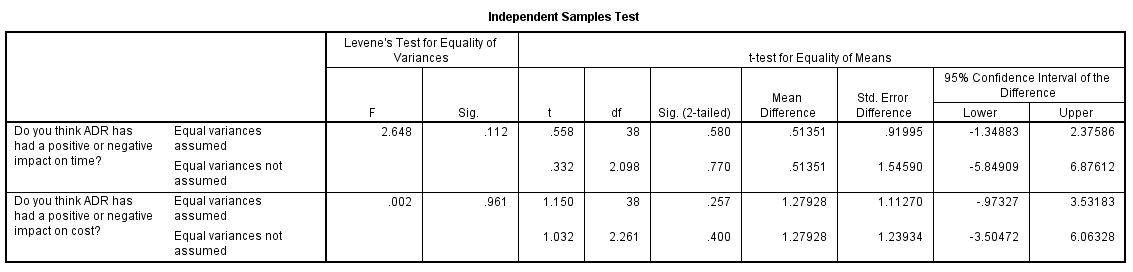

Independent Sample’s T-test

Independent Sample’s t-test is used to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the mean of the two groups. Through this, the opinion of professionals from the construction industry was determined over the positive and negative effects of ADR on time. It costs on their experience of more than 5 years and between 3-5 years. The results of the test are provided as follows:

Independent Sample's T-test

The null hypothesis of the Chi-square is that the first variable (positive effect on time) is independent of the second variable (positive effect on cost), whereas the alternate hypothesis is otherwise. The p-value of the chi-square is 0.00, implying that there is enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis that positive effects on cost and positive effects on time are independent; hence, the alternate hypothesis is accepted that the relationship between positive effects on time and positive effects on costs exists. Therefore, we can conclude that those respondents said that ADR has a positive effect on time and that ADR has a positive effect on cost. This also indicates the importance of time and cost in the construction industry and that if the time of the project increases, then the cost would also increase and vice-versa.

One-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance)

This section analyses variance (ANOVA) to determine if the population mean of multiple groups is significantly different across populations. The null hypothesis of the ANOVA is where the mean of all populations is the same, and the alternate hypothesis is that at least one of the group’s mean is not equal to the population of the other group’s mean. The figure below illustrates the result of ANOVA in which the difference over the most common method of ADR is determined across professionals with different experience levels in construction.

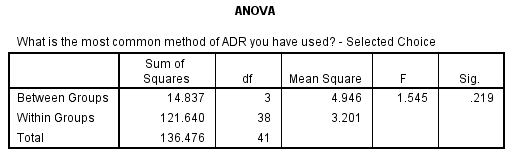

ANOVA Test 1

One-Way ANOVA test 1

Figure 14 above elucidates f=1.54 [Sig. 0.219] suggesting that the sig value of the ANOVA is greater than the selected significance 0.05 (5%); hence, there is enough evidence not to reject the null hypothesis and that all populations across the groups' means are the same. This implies that there is consensus among the industry professions to select the common method of ADR, and experience has no role in determining the method of ADR. It can be interpreted that the consensus among the professionals over the common ADR methods shows that ADR is the most common concept in the construction industry, and each of the professionals, irrespective of experience, prefers ADR to the traditional method of handling disputes.

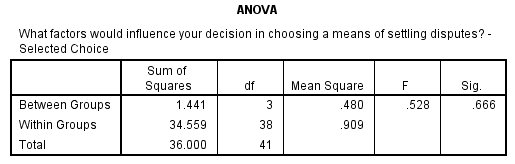

ANOVA Test 2

- One-Way ANOVA test 2

- One-Way ANOVA test 2

The figure above shows the results of the second ANOVA test, where it is tested that there is consensus among professionals in considering factors when choosing a means of settling disputes by differing experience levels. Since the sig value of the test is 0.66, which is higher than the significance level, it is evident that professionals have a consensus in considering the factors when choosing to handle disputes. No role of experience considers those factors. This also implies that experience has no role in choosing the dispute's methods.

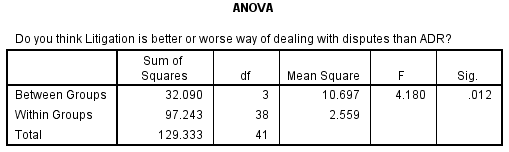

ANOVA Test 3

One-Way ANOVA test 3

One-Way ANOVA test 3

Discussion and Conclusion

Industry professionals have used ADR to solve disputes immediately to save costs and time. It has been discussed by Alaloul, Tayeh, &Hasaniyah (2019) that the construction industry is highly sensitive to time and cost because if a project is delayed, everything associated with it gets affected. However, it is nearly impossible to avoid disputes in the construction industry since the complexity of the contracts has increased, meaning the probability of dispute increases. In this regard, Malleson (2018) argues disagreements may differ in intensity and levels because various parties are involved in a construction project. The NCCLR 2018 has indicated that 19% of the contracts in construction have at least one dispute, and 4% of contracts have four disputes supporting these claims.

It has become common not to have a dispute about construction contracts. The emergence of disputes is not a major issue; conflict resolution between the parties is the major issue since time is money in the industry. In this regard, the literature suggests the most common causes of the disputes among the parties are EOT, final accounts valuation, valuation of variations and non-compliance to the contract obligations (Keane & Caletka, 2015)(Garner, 2015)(Iyer, Chaphalkar, & Patil, 2018)(Aryal & Dahal, 2018). Also, findings from the interview and questionnaire analysis suggested that EOT, valuation issues and non-compliance to contract obligations are the most common reasons behind the disputes.