How National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) Can Contribute in Creating a Sustainable and Healthy Community

December 14, 2022

Determining/To Determine/Determine Employees’ Attitudes Towards Changing Amazon’s Prime Video Services

December 14, 2022 Download PDF File

Download PDF File

Nixon (2014) stated that cyberbullying had become an international public health concern among adolescents. The excessive use of the internet today as a mode of communication has created a potentially harmful yet unique dynamic for social relationships, which can also be called Internet harassment. It is evident to notice a more negative impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health. According to Fahy et al. (2016), there is a difference between cyberbullying and face-to-face bullying. Meanwhile, cyberbullying is predicted to have a greater impact on the mental health of teenagers. Furthermore, several factors, such as publicity, permeability and permanence of online messaging, cause cyberbullying, which is different from face-to-face bullying (Fahy et al., 2016).

159+ Latest Mental Health Dissertation Topics in 2025

These certain features have a significant effect on mental health such that the sharing of online messages and the intention to defame someone for revenge create psychological problems like depression, anxiety, self-injurious behaviour and suicidal thoughts are most common among adolescents (Skilbred-Fjeld, Reme and Mossige, 2020; Hellfeldt, López-Romero and Andershed, 2020). According to the study of Whittaker and Kowalski (2015), it can be difficult for someone who is cyberbullied to tell their friends and families about being bullied. Additionally, friends and families must adhere to the following factors to evaluate whether an individual is being bullied or not. These factors include becoming withdrawn as soon as they use their smartphone or computer, being afraid of going out or to any crowded social event and many other factors (Whittaker and Kowalski, 2015).

The following are the aims and objectives of the study.

Aim and Objectives

To investigate cyberbullying involvement and its effects on adolescents' mental health in the UK.

-

Objectives

- To comprehend the difference between bullying and cyberbullying.

- To identify the factors associated with cyberbullying that lead to cybercrimes

- To analyse the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health in the UK.

- To identify the emotional and social consequences of cyberbullying and their relative effects on mental health.

- To provide realistic recommendations in mitigating cyberbullying practices, especially from adolescents' perspective.

Research Rationale

According to Fahy et al. (2016), in the last decade, cyberbullying has emerged significantly as a new form of bullying. The media and researchers have focused a lot on the increased suicides due to mental depression and internet harassment. Additionally, Nixon (2014) stated that technological advancement has increased cyberbullying, thereby increasing the negative impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health and disturbing their psychological well-being as an intentional act of aggression. The initial work in this new construct was documentation on the identification of similarities and dissimilarities of bullying, its prevailing rates and the sex-related effects, but the establishment of a relationship between psychological disorders among adolescents and cyberbullying is an area of research needs to be explored (Skilbred-Fjeld, Reme and Mossige, 2020; Nixon, 2014). Therefore, this study will analyse the consequences of cyberbullying and its involvement in the mental health of teenagers to fill in the research gap.

Use of Psychodynamic Therapy in Treating Depression in Teenagers

Waasdorp and Bradshaw (2015) highlighted that cyberbullying affects adolescents' mental health in such a way that it induces depression, lowers their self-esteem and increases their chances of committing suicide. Patchin and Hinduja (2015) explain that 10% of adolescents commit suicide because of cyberbullying, and more than 30% have increased suicidal thoughts due to this phenomenon. Additionally, the study of Brewer and Kerslake (2015) elucidates the relationship between cyberbullying and adolescent mental health by stating that the former makes the latter feel exposed and humiliated. It is because these individuals acknowledge that once any information, picture, or video enters cyberspace, it stays there forever, which makes them feel exposed to the whole world. This is a fact that makes adolescents vulnerable and affects their mental greatly because they never feel safe anywhere they go.

The study of Aboujaoude et al. (2015) shows that cyberbullying has a positive relationship with causing depression in adolescents. The results indicate that higher levels of cyberbullying were related to adolescents having higher levels of depression. Furthermore, Barlett, Gentile and Chew (2016) conducted an open-ended survey in which the target audience was adolescents who had or were experiencing cyberbullying 93% of the participants reported having negative effects, and the majority of the participants reported having feelings of hopelessness, depression, sadness, and powerlessness. Another experiment conducted by Bottino et al. (2015) showed that there is a positive relationship between depression and cyber victimization in adolescents. Their results demonstrated that there were varying levels of depression within each adolescent. Brody and Vangelisti (2016) conducted a study in America to find out about cyberbullying in adolescents. The results obtained in their study showed that half of their sample size was not aware of the person bullying them through the internet. This aspect consequently increased their fear of living and affected their mental health.

The rationale of this research is that the effect of cyberbullying has been researched in adolescents in many countries of the world. The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health has been explored in Finland (Sourander et al., 2010), Turkey (Aricak et al., 2008), Germany (Katzer, Fetchenhauer and Belschak, 2009), USA (Wigderson and Lynch, 2013), Sweden (Slonje, Smith and Frisén, 2012), Australia (Hemphill et al., 2012), Canada (Bonanno and Hymel, 2013), and many other countries as well. However, limited research could be obtained on the effects of cyberbullying on the mental health of adolescents in the UK. Thus, this research contributes to the body of knowledge by researching the negative association between cyberbullying and adolescent mental health in the UK.

Research Methodology

A research methodology is known as a specific set of procedures and techniques used to identify, select and analyse the collected data to yield related information about the research topic. This section of the research allows the researcher to critically assess the data for the overall reliability and validity of the study (Kumar, 2019). The selected methods and techniques are explained below.

-

Research Philosophy

The philosophy that was adopted for this study pertains to the philosophy of Interpretivism. The philosophy of interpretivism was adopted for this study because it allowed the researcher to observe the phenomenon of cyberbullying and analyse its impact on adolescents' mental health (Caldwell, 2015). It also pertains to collecting qualitative data gained through observing real-world phenomena (Caldwell, 2015). Moreover, interpretivism is limited to collecting and qualitatively interpreting data to find patterns and ideas by making meaningful inferences from the observations made (Ryan, 2018). Therefore, the interpretivism philosophy was beneficial for this study. It allows the researcher to collect qualitative data by observing a real-world phenomenon and formulating findings because it provides a deeper understanding of the research topic as a humanistic approach.

-

Research Approach

Another research approach that was adopted for this study was the inductive approach. According to the study of Pandey (2019), the inductive approach in research pertains to the development of reasoning from a general aspect to a specific one. An inductive approach was adopted for this study because it allowed the researcher to develop a hypothesis targeted for developing a theory by finding similar patterns and ideas by observing real-world phenomena (Pandey, 2019). In this case, the inductive approach was employed to investigate the involvement of cyberbullying and its effect on adolescents' mental health in the UK. The advantage of employing the use of the inductive approach for this research is that it allowed for a greater understanding of the topic under research, induced greater flexibility in the study, evaluated the contexts of observations and research, and allowed for support for the generation of a new idea, phenomena or theory (Antwi and Hamza, 2015).

-

Research Method

A secondary research method was used in this research, in which the researcher reviewed the studies of past authors to obtain data for this study. The previous studies were examined by conducting a literature matrix which effectively identified the extent of the research analysed by key authors of the published articles related to the research objectives. The secondary method was employed because it allowed obtaining honest and trustworthy information by reviewing already available articles, books, journals, websites and other materials (Keusch, 2015). Additionally, the secondary research method was beneficial for the current study as it provides up-to-date information, better accuracy, a higher level of control, and addresses specific research issues (Thomas, 2015). The method is beneficial in collecting a huge amount of data on the key themes of the research. Also, the secondary method provides ease for the researcher because it is cost-effective and less time-consuming (Keusch, 2015). The databases, including Google Scholar, CINAHL, and Open Library, were searched to review the past data from studies published in books, articles, journals, newspapers, authentic websites and other relevant and authentic sources through which high-quality data were obtained.

-

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the current study were decided based on the research aim and objectives to ensure the quality of the research. In this study, the literature studies included in the research were from 2008 and onwards. Moreover, the research articles included in the study were narrowed down to three main themes: factors leading to bullying involvement, the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health, and the consequences of cyberbullying on mental health. The research studies that were not published in peer-reviewed journals were excluded from the research because only published studies provide authentic and valid results. Additionally, the data included in the research was focused on UK adolescents.

-

Data Collection Method

The data collection method adopted for this study pertains to the qualitative research method because it allowed the researcher to develop the aim and objectives of the study. The qualitative research method was adopted because it allowed for comprehension of the topic under research qualitatively by making observations, interviewing concerned personnel and inferencing patterns from the observations done (Inoue et al., 2015). According to the study of Hartas (2015), the qualitative data collection method is the process employed in research to obtain insight into the research problem and aids in the development of ideas for the study. This methodology also helps to gain a deeper grasp of the fundamental reasons, opinions and motivations. The benefit of employing the qualitative method is that the data obtained through this method is valid, authentic, trustworthy and reliable, which aids a researcher in developing a high-quality research document (McCusker and Gunaydin 2015). Thus, a qualitative method was adopted because it allowed the researcher to gather qualitative data on the concept of cyberbullying and its impact on the mental health of adolescents. Moreover, it enabled the researchers to collect data quickly and with minimal human interaction to obtain authentic and reliable data.

-

Data Analysis Method

The data analysis method employed for this research pertains to content analysis, whereby content analysis was employed to analyse the data obtained through the secondary data collection method. A research tool which is used to determine certain themes, words or concepts with some collected qualitative data is known as content analysis. It allows the researcher to analyse the available data by analysing the content and adding content that matches the themes of the study related to assessing the results for the research objective in an efficient manner (Neuendorf, 2016). The employment of content analysis allowed the researcher to analyse the patterns in the content being added to the research and analyse the social phenomena being discussed in this research from various perspectives.

-

Ethical Issues

It was ensured that the researcher executed this study free from plagiarism and gave appropriate credit to authors whose study has been referred to for data collection, which is also necessary to show the credibility of the collected data. All materials employed for this study were cited and included in a list of references at the end of the study, and credits were given to the authors. Furthermore, the researcher avoided the employment of any unpublished data or data from unauthentic sources, which would diminish the quality of this study. All data obtained was only used for this study and in no form or manner employed for other purposes.

Thematic Literature Including Findings and Analysis

According to the study of Navarro, Yubero and Larrañaga (2015), bullying of an individual can be described as an act of inflicting pain or damage to other individuals in a manner not seemingly appropriate for society.

-

Difference Between Cyberbullying and Bullying

Bullying or traditional bullying is done physically, whereby the perpetrator threatens the victim in an aggressive and threatening manner (Zaborskis et al., 2018). The main aim of bullying is to cause pain to the victim, and the perpetrator is fully aware of this fact and intentionally performs such an activity. Similarly, Aricak and Ozbay (2016) explain that cyberbullying does not have much difference from traditional bullying because in both cases the aim is to damage the victim's reputation and cause them harm. However, González-Cabrera et al. (2017) highlight that the only difference between cyberbullying and traditional bullying is that the perpetrator is not face-to-face with the victim and causes them harm through cyberspace.

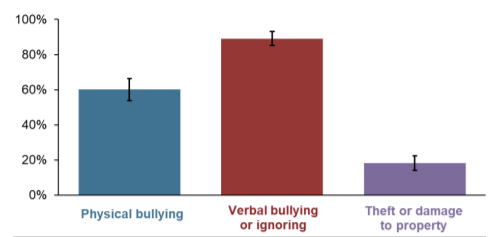

Similarly, it has been analysed that bullying is defined as repetitive harassment, threats, mistreatment or making fun of other people; however, cyberbullying is different from bullying in that it is harassment done using electronic devices and the internet (Patchin, 2016). Therefore, it can be evaluated that cyberbullying is disadvantageous for the victim because they are not aware of their perpetrator and live in constant fear of others. However, in traditional bullying, the victim is aware of their perpetrator and, thus, with enough confidence and the power of will, can face their perpetrators. Moreover, bullying can be classified further, for example, physical bullying, such as pushing, hitting, and harassment, verbal bullying, such as teasing, insulting or name-calling, and bullying in a relationship etc. Cyberbullying is mostly related to using social media sites to defame someone, such as spreading rumours, exposing secrets, etc. (Patchin, 2016). A survey reported the estimated results from April 2017 to March 2018, in England youngsters aged between 10 and 15 were bullied, and verbal bullying was the most commonly reported behaviour to those living in deprived areas, having any disability and having a non-British ethnic background (APS UK, 2018).

Bullying in England (APS UK, 2018)

Verbal bullying was the most common type of bullying (APS UK, 2018)

Fahy et al. (2016) investigated 2,480 teenagers participating in the Olympic Regeneration in East London between 12 and 13. The results presented that at baseline, 14% of teenagers were cyber victims, and 8% were reported as cyberbullies. Furthermore, the 2014 HSBC study identified that girls are bullied twice as boys, and the most prevalent age of being cyberbullied in the UK is 15, and these young people mostly belong to affluent families (APS UK, 2014). The outcomes of traditional bullying and cyberbullying on adolescents are the same for the victim because, in both cases, the victim feels depressed and lonely, their eating and sleeping patterns change, and they lose interest in most activities (Zsila et al., 2019). However, according to the study of Wegge et al. (2016), although the outcome of both bullying methods is the same, cyberbullying has a much greater and deeper impact on the adolescent victim than traditional bullying.

This is because, according to the study of Fahy et al. (2016), the victim is knowledgeable of their perpetrator in traditional bullying. At some point in life, they can take their revenge or, in some cases, completely take a separate path so that they do not have such encounters again. Nonetheless, the same cannot be said for cyberbullying because the victim and the perpetrator are both present in cyberspace, and there is no method of completely avoiding the perpetrator (González-Cabrera et al., 2018). Moreover, anything uploaded into cyberspace by the bullying person cannot be deleted from the internet, and the victim has no choice but to accept the reality of the situation (Kim et al., 2019).

Another main difference between traditional bullying and cyberbullying is that the internet offers the offender an extra layer of protection in the sense that they can remain completely anonymous and still bully their victims (Coyne et al., 2017). Even though some methods can allow the victim to know their perpetrators, they fail in most cases (Wright, Harper and Wachs, 2019).

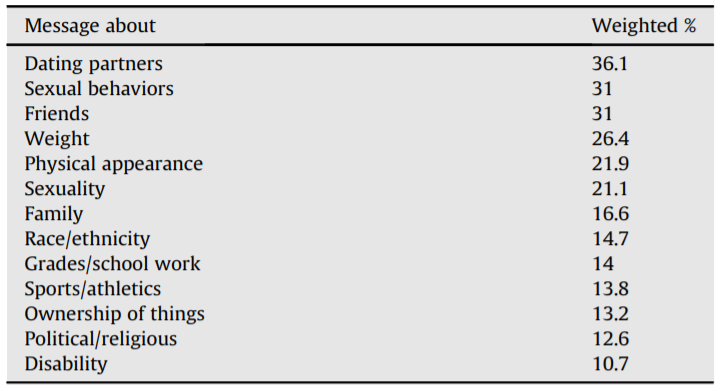

Internet Censorship in the UAE

According to the study of Hase et al. (2015), cyberbullying can happen anytime and anywhere as long as the offender has access to the internet. In the research by Waasdorp and Bradshaw (2015), it has been investigated that the rise in cyberbullying among adolescents is due to less online supervision and easy access to electronic devices. The results were examined from 28,104 high school adolescents in grades 9-12. 23% of them were resulted to be suffered from verbal, relational and physical bullying, whereas 25.6% were victims of cyberbullying. The most common behaviour for cyberbullying identified was dating partners (Waasdorp and Bradshaw, 2015).

What was the cyberbullying message about? (Waasdorp and Bradshaw, 2015)

Furthermore, Wachs et al. (2017) differentiate cyberbullying from traditional bullying because the latter is more isolated, whereas cyberbullying, in a sense, is more public. The study of Del Rey et al. (2016) explains traditional bullying does not facilitate the path of the incident becoming popular. Still, cyberbullying can cause the incident to go viral over the internet, ruining the individual's life completely. Hence, in light of the previous statement, Graham and Wood Jr (2019) elucidate that although individuals can be hostile both offline and online, the major difference between the two bullying methods is that information, videos or pictures can be easily shared on the internet, which could potentially create a chain reaction of sharing the post consecutively to the whole world.

-

Factors for Cyberbullying Involvement Effecting the Mental Health of Adolescents

Machackova and Görzig (2015) state that involvement in cyberbullying involves vulnerable groups such as individuals having psychological difficulties, being a girl and social disadvantages in the UK. Moreover, resilience factors were identified as self-efficacy, sensation seeking, lack of social support and internet use. Further, cultural factors such as crime rates and attitudes towards equality were identified. While through a broad perspective, three categories of factors of involvement in cyberbullying that affect mental health are individual, social and cultural factors (Machackova and Görzig, 2015). Additionally, individual-level factors include demographic variables (ethnicity, gender and age), psychological variables (self-efficacy, sensation seeking, psychological difficulties and ostracism, internet activities) and usage variables (online activities, excessive internet usage and online persona).

Moreover, other important one include internet skills variables (receiving and sending sexual messages, digital skills, meeting new online contacts, personal data misuse and seeing sexual pictures) and offline variables (missing school, getting in school trouble or with the police, and getting drunk) (Machackova and Görzig, 2015). Social factors include: being a member of a discriminative group, having socio-economic status, and being considered to have a disability such as mental, physical or learning. Moreover, parental factors were also identified (Machackova and Görzig, 2015). For example, according to Cowie (2013), UK college students had more anxiety, depression, paranoia or phobic anxiety, affecting their mental health due to being involved in cyberbullying. Moreover, these students said they do online bullying because they feel isolated, unsupported by teachers and parents, and sometimes unsafe emotionally at home and school.

In the study of Li (2010), in the UK, 45% reported that various factors cause involvement in cyberbullying: feeling insecure, jealous, angry having family issues. 64% reported that they do it for “fun”, and 1 in 5 people perceive bullying as an act of being “cool”. For example, students in the UK who were involved in cyberbullying had fewer friends, were mostly pessimistic, and had lower social acceptance. One of these students said that he bullies other people online, which means nothing to him (Betts, Spenser and Gardner, 2017).

In demographic factors, 6% of participants reported being a victim of cyberbullying, while 3% reported that they had bullied other people due to age or gender. In offline bullying, 56% reported that they bullied other people face to face, while 55% reported that they bullied others online (Machackova and Görzig, 2015). Moreover, almost 60% reported being bullied by others either offline or online. Individuals who bullied others were themselves bullied, and the ratio was found to be 10% (Machackova and Görzig, 2015). In social factors, 6% of adolescents and parents reported online bullying of the youth. Of those adolescents who were bullied online, 29% of their parents knew about their online bullying, 56% of parents stated that their kids were not bullied online 15% reported that they did not know or doubt it, and 8% of parents of non-victimised adolescents indicated that their kids had been bullied online (Machackova and Görzig, 2015).

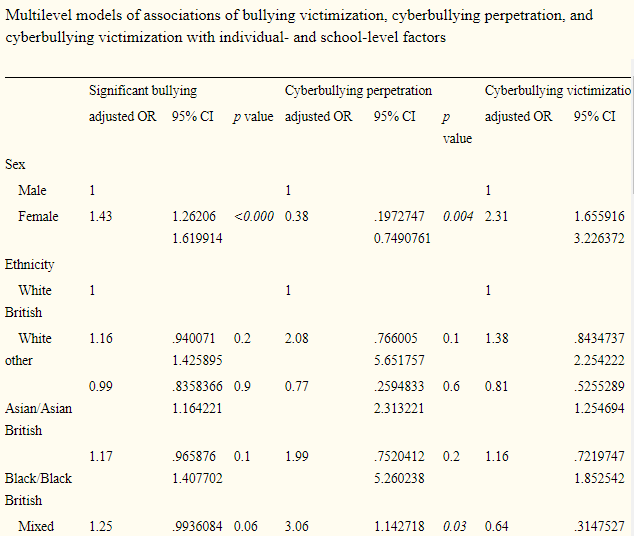

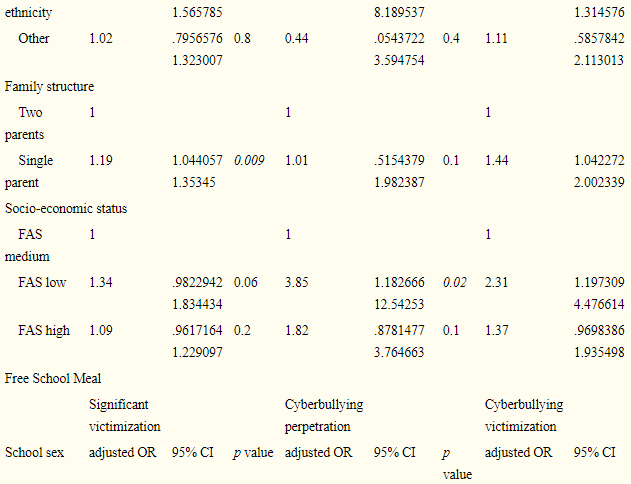

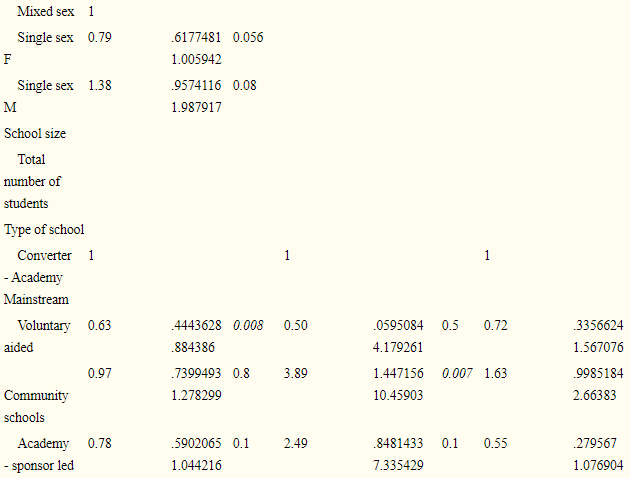

According to Gaffney and Farrington (2018), the factors for cyberbullying involvement are psychological and cognitive factors, including loneliness and low self-esteem in the UK. Similarly, Shin and Ahn (2015) added that psychology, school, demographic and media-related factors affect adolescents' involvement in cyberbullying. Bevilacqua et al. (2017) state that factors associated with an individual, such as ethnicity, family composition, gender and SES, relate to cyberbullying outcomes and affect the mental health of youth in the UK. School-level factors were also identified. 10% interaction was found between all school-level and individual-level factors (Bevilacqua et al., 2017).

(Bevilacqua et al., 2017)

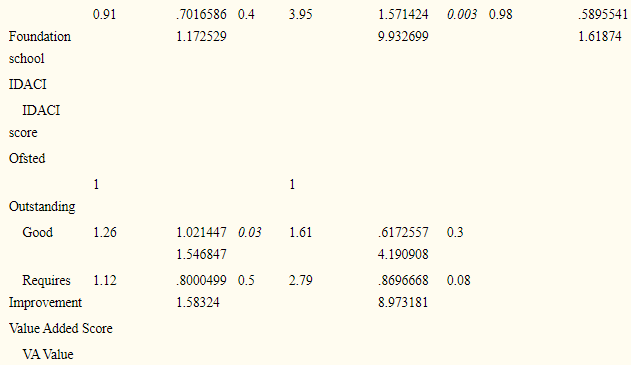

Hellfeldt, López-Romero and Andershed (2020) have identified the lack of social support as a cause of cyberbullying involvement and affects the mental health of young adolescents in the UK. Moreover, factors related to involvement in cyberbullying in the UK are recognised at levels of the socio-ecological system: cultural, individual levels, and social environment. The statistics are shown below:

(Hellfeldt, López-Romero and Andershed, 2020)

-

The Impact and Emotional and Social Consequences of Cyberbullying and Its Relative Effects on Mental Health

The research of Routledge. Heiman, Olenik-Shemesh and Eden (2015) contemplated that involvement in cyberbullying negatively impacts the mental health of adolescents in the UK. A similar author elaborated that one of the major impacts of cyberbullying involvement on adolescents' mental health is suicidal tendencies; victims of cyberbullying consider it as mental torture (Routledge Heiman, Olenik-Shemesh and Eden, 2015). At the same time, the research of Nixon (2014) indicated that the effect of cyberbullying involvement on adolescents' mental health in the UK has resulted in poor academic performance. In the study of Hamm et al. 2015, the author provided a good example of one of the respondents in the UK who indicated that he began to face the issue of anxiety and depression after getting involved in cyberbullying because he has a fear of being caught and getting a lawsuit. The study by Gualdo et al. (2015) experimented to determine the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health. Within their selected participants, they found that 86% per cent had access to the internet via their cell phones, while the rest used the internet on their PC and only for a short amount of time. According to a study by Navarro et al. (2015), the perpetrators who indulge in the habit of cyberbullying cosset themselves with increased substance use, higher levels of aggression and aberrant behaviours. Furthermore, there is a variance in cyberbullying prevalence rate ranging from 4% to 72%, with average reports of victims ranging from 20% to 40% in adolescents (Albdour et al., 2019). Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be devised;

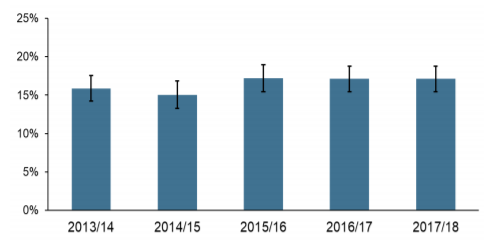

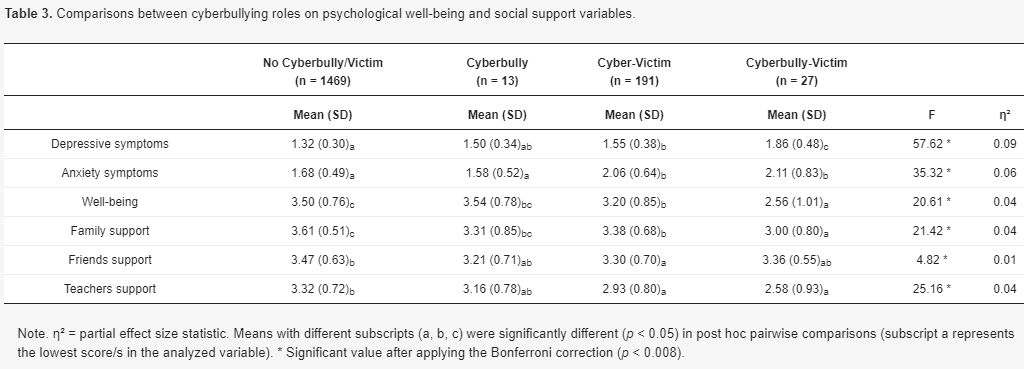

According to the study by Muhonen, Jönsson and Bäckström (2017), cyberbullying is one of the major threats that can affect an individual's mental health. A similar author elaborated that cyberbullying makes a victim feel humiliated due to a person's mental health, such as losing confidence (Muhonen, Jönsson and Bäckström, 2017). Similarly, the studies of Gualdo et al. (2018); and Meter and Bauman (2018) asserted that the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health in the UK had restricted teens from participating in co-curricular activities such as sports, debates and other activities. Furthermore, the studies of Fahy et al. (2016) presented the following figure to highlight the prevalence of cyberbullying in the UK. Additionally, the research of Miller (2016) contemplated that cyberbullying has been a primary cause of making an individual vulnerable, consequently affecting their self-esteem.

Furthermore, the studies of Mishna et al. (2016); and Menesini and Spiel (2013) stated that cyberbullying results in making victims hopeless towards life; the victims begin to find their lives meaningless as the incident of cyberbullying has negatively affected their mental health. Similarly, the studies of Miller (2016) highlighted that cyberbullying results in harmful mental diseases such as depression and anxiety, due to which the victim loses their self-confidence. However, the research of Menesini and Spiel (2012) indicated that cyberbullying is one of the reasons that inclines a victim towards suicide as such event leads to extensive tormenting from peers and fellows via text messages and social media platforms.

Cyberbullying (McCarthy, 2018)

The above figure illustrates the prevalence of cyberbullying across the globe to support the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health in the UK. The figure presented that 17% of children across the UK experienced cyberbullying in the year 2018 and shared it with their parents (McCarthy, 2018). In addition, the studies of Nixon (2014) contemplated that the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health in the UK has prevented individuals from going to school due to stress from the event. However, the studies of Fahy et al. (2016) identified that cyberbullying involvement could affect adolescents' mental health by inclining them to commit violence as revenge for the cyberbullying event. Also, the study of Meter and Bauman (2018) indicated that self-harm is one of the major impacts of cyberbullying on the mental health of children in the UK. A similar author added that the young victims of cyberbullying face extensive mental pressure from society and friends after the event, which results in self-harming behaviour such as bruising themselves with unkind words or self-harming physically (Meter and Bauman, 2018).

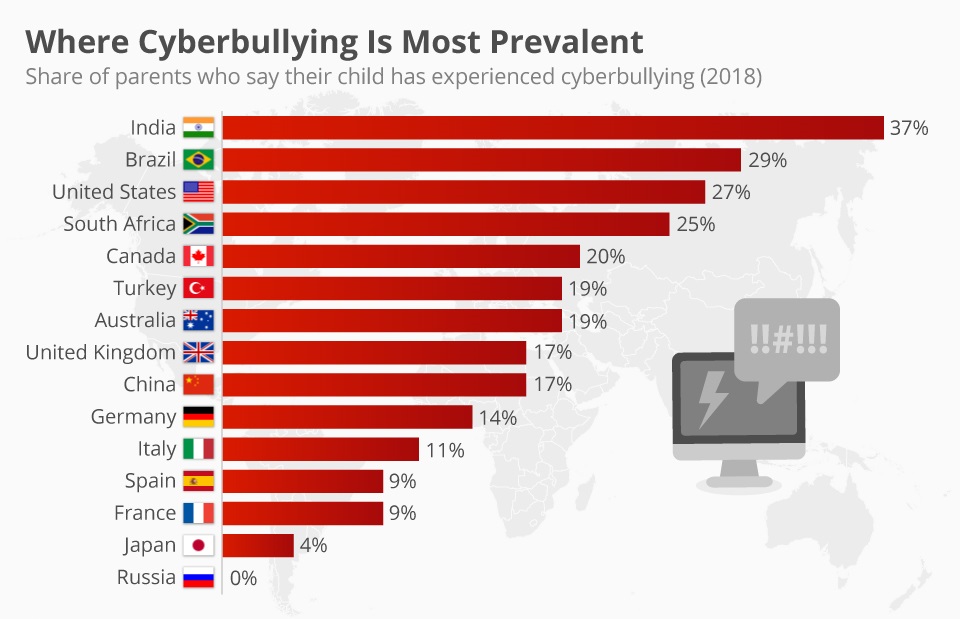

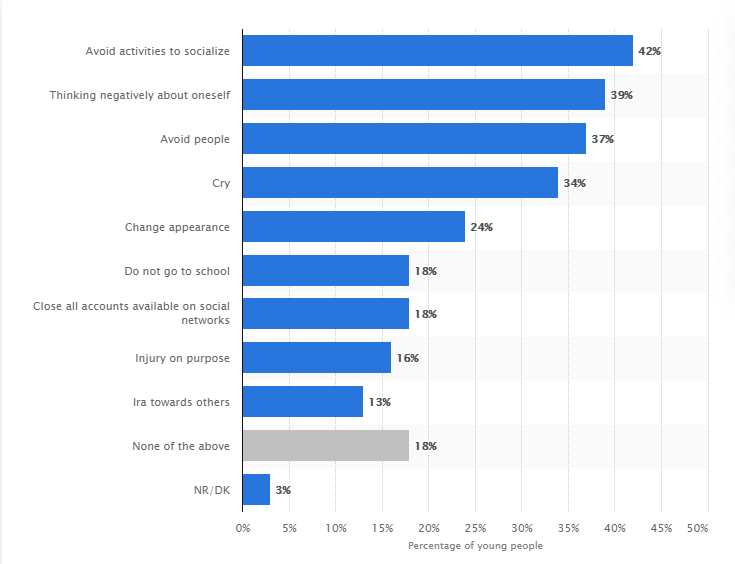

Consequences Experienced By Young Victims of Cyber Bullying (Statista. 2015)

The above figure highlights the consequences of cyberbullying faced by young victims. The statistics revealed that approximately 42% of individuals become dissocialised, 39% lose self-esteem, 37% avoid meeting people, and 34% cry due to cyberbullying (Statista. 2015). The above-indicated consequences can be evaluated as an effect on mental health due to the event of cyberbullying among young individuals.

The study of Muhonen, Jönsson and Bäckström (2017) identified that cyberbullying makes an individual feel ill and withdraw their focus on other elements of their life such as well-being, education and healthcare. Furthermore, the studies of Menesini and Spiel (2013); and Pingault and Schoeler (2017) stated that cyberbullying makes the victims angry and vengeful, due to which they get involved in unethical activities such as crimes and threats to take revenge. According to Spears et al. (2015), cyberbullying has many adverse consequences on the victim that could continue for a longer period than what is attributable to the involvement of traditional bullying. The study of Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton (2015) explains that there is plausible evidence that cyberbullying adversely affects mental health. For instance, loneliness, depression and social anxiety have been identified as common risk factors in victims.

Another relative mental effect of cyberbullying found by Wachs et al. (2016) study is the effect of anxiety and depression. Since in cyberbullying, the interactions are not occurring in the real world, and these interactions are through the internet, offenders tend to say things that they would not be able to communicate face-to-face under normal circumstances. This leads them to social anxiety and depression, and since this information is on the internet, they can't delete it (Brewer and Kerslake, 2015) completely. Furthermore, Varghese and Pistole (2017) elucidate that 58% of adolescents in the UK suffer from social anxiety when cyberbullied, and nearly 53% have increased levels of depression and develop mild social passive-aggressive behaviour. Such adverse mental effects of cyberbullying are long-lasting and leave a permanent impression on their lives. Due to these factors, they are still unable to live normally even after the bullying has stopped (Wolke, Lee and Guy, 2017). In the study of Zezulka and Seigfried-Spellar (2016), the author explains that the Pew Research Centre conducted a survey in the USA, and the results showed that nearly 75% of teenagers and adults have witnessed cyberbullying. More than 40% have themselves become victims.

Emotional Consequences

By the study of Selkie et al. (2015), many studies present a positive relationship between cyberbullying and the occurrence of emotional and behavioural problems in individuals, especially adolescents. Additionally, Kim et al. (2018) explain that the consequence of both traditional bullying and cyberbullying is more severe in individuals who experience both types of bullying simultaneously. In other words, they are being harassed physically and through cyberspace. The consequence of cyberbullying and its relative effect on mental health has a positive relationship, as explained by Miller (2016). Moreover, victims perceive behavioural and emotional problems, reduced self-respect, and increased substance use. According to the study of Giumetti and Kowalski (2016), the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health is more severe if they have already been emotionally abused due to other circumstances and not bullying.

Social Consequences

The findings of the study of Palermiti et al. (2017) depict that cyberbullying has a significant association with the reduction of self-confidence in the victim. Along with lower levels of confidence, victims of cyberbullying try to exclude themselves from others, meaning they prefer loneliness rather than socialising with others (Extremera et al., 2018). Along with the mental health effects of loneliness, depression and social anxiety, cyberbullying is also associated with reduced self-confidence, making it difficult for the victims to interact with other people in their lives and make new friends (Mishna et al., 2016). Moreover, the factor of loneliness is associated with the victim when the perpetrator successfully manages to bully them through cyberspace and ensures that the victim is also being rejected in their social gathering (Hamm et al., 2015). Further in their research, the cyberbullied victims reported that they were being bullied on multiple social platforms and received personal messages on their number that included derogatory sentences. Many of these participants reported that they were unaware of their perpetrator and constantly feared something happening to them, so they reduced all contact with their social group (Gualdo et al. 2015). The research of Pingault and Schoeler (2017) contemplated that cyberbullying frequently forces an individual to go in isolation and that negatives harm a person's mental health as their social need do not get fulfilled.

HO: There is no significant impact of cyberbullying involvement on adolescents' mental health.

H1: There is a significant impact of cyberbullying involvement on adolescents' mental health.

Conclusion

The emerging form of bullying and threatening is cyberbullying, in which the electronic means the victim is harmed and he is not even aware of the perpetrator. The difference is also identified from the research findings that traditional bullying is more isolated. In contrast, the sense of cyberbullying is more public as cyberbullying incident goes viral and ruin the life of a person at the next level than bullying because of the sharing of personal information, videos or pictures publically.

Further, the research explored the factors associated with cyber-involvement, such as permeability, publicity, and permanence of online messaging, which is a significant reason for cyberbullying and affects adolescents' mental health. In addition, the factor of loneliness in the victim makes the perpetrator significantly involved in bullying through cyber-space. Additionally, factors related to cyberbullying involvement in the UK are analysed at different levels of the socio-ecological system: cultural, social environment and individual levels.

The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health was also the research's major objective to investigate. The research evaluated that if the adolescents have already been suffering from severe emotional abuse, they are more about the mental health problems caused by cyberbullying and most likely to have increased levels of extreme anger, dissociation, and depression. The negative consequences of cyberbullying that affect mental health are investigated as a reduction in self-confidence, difficulty in socialising, and loss of meaning in life. Moreover, these consequences cause some mental health effects of cyberbullying on adolescents, such as loneliness, depression and social anxiety. Additionally, cyberbullying is mostly from anonymous perpetrators. This fear of the unknown harming an individual hugely impacts adolescents' mental health, and the rates of substance use and suicides become prevalent. Therefore the hypothesis for the research proved to be true that cyberbullying involvement has a significant impact on adolescents' mental health.

Cyberbullying has become a serious threat to adolescents in the last decade and has become a major concern of researchers investigating the overall effects and impact of cyberbullying on young people. Therefore, this study has analysed the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health and investigated the effects and negative consequences of cyberbullying. The research has highlighted the difference between traditional bullying and cyberbullying. It was explored that the increased cyberbullying significantly affects adolescents’ well-being, and its higher rates are growing psychological problems among young people, such as depression, anxiety, self-injurious behaviour and suicidal thoughts. Moreover, it proved a hypothesis made after evaluating the research objectives through secondary analysis that cyberbullying involvement significantly impacts adolescents' mental health. Further, it has been highlighted in the research that the role of parents and schools is essential in creating awareness regarding cyberbullying among adolescents to decrease its high rates. Technological changes can also be beneficial as a mitigation practice for cyberbullying.

Guaranteed AI-Free Work

Protect your degree from AI-Objectifying! Get 100% human generated research content!

Recommendations

Cyberbullying in the UK is prevailing, especially among adolescents and has adverse effects on the mental as well as physical health of adolescents. Therefore it is essential to raise awareness among healthcare professionals, educators, parents and, most importantly, adolescents related to the serious nature and impact of cyberbullying to reduce it. Following are a few recommendations for mitigating cyberbullying practices, especially from adolescents' perspective.

- Bullying mainly starts in school; therefore, there should be cyberbullying prevention and intervention programs at school targeting teenage students in particular. It can be done by addressing adolescents’ beliefs at both individual and classroom levels around cyberbullying. The student should also be trained in effective coping strategies for cyberbullying and its negative effects.

- Parents can play an effective role in preventing their children from being victims or perpetrators of cyberbullying by providing them with emotional support and awareness regarding the negative consequences of cyberbullying. Further, they can use some prevention efforts related to cyberbullying, such as enhancing their children’s self-esteem and empathy, promoting warmth, reducing their time spent online and nurturing their relationships with their children. Most adults are likely to hide their cyberbullying experiences from their parents. However, an effective connection and check on children by parents can reduce the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health.

- The schools, districts, governments and legal institutions are recommended to introduce new laws addressing cyberbullying in specific and electronic harassment, which can surely be effective in reducing the risk of increased cyberbullying activities associated with social media. They should also create awareness among individuals that they should report these incidents without being threatened if they face cyberbullying.

- Some technological advancements can also help reduce cyberbullying, such as firewall blocking services, mobile parental control, online reporting facilities, slanderous email blocking, IP address tracking applications, online service rules, etc.

Guaranteed Plagiarism-Free Work

Get 100% human generated plagiarism-free research content from our expert writers!

Future Implications

The current research has investigated cyberbullying involvement and its effects on adolescents' mental health in the UK. It has also evaluated the factors associated with it and the mental health problems faced by adolescents who suffer from cyberbullying. The current research benefits adolescents and youngsters as it can create awareness among them about the prevailing rates of cyberbullying. Further, the research has provided some useful recommendations that can help parents know that cyberbullying can be more adverse than traditional bullying and they might not even be aware if their children are suffering. The research has provided strategies for parents to support their children and teach them how to be secure from harmful acts of cyberbullying.

Moreover, this research is also helpful for the schools, government and communities to know the fact that the negative consequences of cyberbullying require strong implications for adolescents especially. Lastly, the current research is also beneficial for future researchers interested in investigating the related research area. The current research could be carried out using primary methods by collecting data through interviews or questionnaires to assess the individual experiences of cyberbullying and bullying. In future, the current study can be analysed with extended objectives, such as the difference between bullying and cyberbullying based on gender, cultural and social aspects.

Connect With Writer Now

Discuss your requirements with our writers for research assignments, essays, and dissertations.

Download PDF File

Download PDF File

References

Aboujaoude, E., Savage, M.W., Starcevic, V. and Salame, W.O., 2015. Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. Journal of adolescent health, 57(1), pp.10-18.

Albdour, M., Hong, J.S., Lewin, L. and Yarandi, H., 2019. The impact of cyberbullying on physical and psychological health of Arab American Adolescents. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 21(4), pp.706-715.

Antwi, S.K. and Hamza, K., 2015. Qualitative and quantitative research paradigms in business research: A philosophical reflection. European journal of business and management, 7(3), pp.217-225.

APS UK. 2014. Cyberbullying: An Analysis Of Data From The Health Behaviour In School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey For England, 2014. [Online] Available at: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/621070/Health_behaviour_in_school_age_children_cyberbullying.pdf> [Accessed 15 April 2020].

APS UK. 2018. Bullying In England, April 2013 To March 2018. [online] Available at: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/754959/Bullying_in_England_2013-2018.pdf> [Accessed 15 April 2020].

Aricak, O.T. and Ozbay, A., 2016. Investigation of the relationship between cyberbullying, cybervictimization, alexithymia and anger expression styles among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, pp.278-285.

Aricak, T., Siyahhan, S., Uzunhasanoglu, A., Saribeyoglu, S., Ciplak, S., Yilmaz, N. and Memmedov, C., 2008. Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology & behavior, 11(3), pp.253-261.

Barlett, C.P., Gentile, D.A. and Chew, C., 2016. Predicting cyberbullying from anonymity. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(2), p.171.

Betts, L.R., Spenser, K.A. and Gardner, S.E., 2017. Adolescents’ involvement in cyber bullying and perceptions of school: The importance of perceived peer acceptance for female adolescents. Sex roles, 77(7-8), pp.471-481.

Bevilacqua, L., Shackleton, N., Hale, D., Allen, E., Bond, L., Christie, D., Elbourne, D., Fitzgerald-Yau, N., Fletcher, A., Jones, R. and Miners, A., 2017. The role of family and school-level factors in bullying and cyberbullying: a cross-sectional study. BMC pediatrics, 17(1), p.160.

Bonanno, R.A. and Hymel, S., 2013. Cyber bullying and internalizing difficulties: Above and beyond the impact of traditional forms of bullying. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(5), pp.685-697.

Bottino, S.M.B., Bottino, C., Regina, C.G., Correia, A.V.L. and Ribeiro, W.S., 2015. Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Cadernos de saude publica, 31, pp.463-475.

Brewer, G. and Kerslake, J., 2015. Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in human behavior, 48, pp.255-260.

Brody, N. and Vangelisti, A.L., 2016. Bystander intervention in cyberbullying. Communication Monographs, 83(1), pp.94-119.

Caldwell, B., 2015. Beyond positivism. Routledge.

Cowie, H., 2013. Cyberbullying and its impact on young people's emotional health and well-being. The Psychiatrist, 37(5), pp.167-170.

Coyne, I., Farley, S., Axtell, C., Sprigg, C., Best, L. and Kwok, O., 2017. Understanding the relationship between experiencing workplace cyberbullying, employee mental strain and job satisfaction: A dysempowerment approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(7), pp.945-972.

Del Rey, R., Lazuras, L., Casas, J.A., Barkoukis, V., Ortega-Ruiz, R. and Tsorbatzoudis, H., 2016. Does empathy predict (cyber) bullying perpetration, and how do age, gender and nationality affect this relationship?. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, pp.275-281.

Extremera, N., Quintana-Orts, C., Mérida-López, S. and Rey, L., 2018. Cyberbullying victimization, self-esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescence: does emotional intelligence play a buffering role?. Frontiers in psychology, 9, p.367.

Fahy, A.E., Stansfeld, S.A., Smuk, M., Smith, N.R., Cummins, S. and Clark, C., 2016. Longitudinal associations between cyberbullying involvement and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), pp.502-509.

Gaffney, H. and Farrington, D.P., 2018. Cyberbullying in the United Kingdom and Ireland. In International Perspectives on Cyberbullying (pp. 101-143). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Giumetti, G.W. and Kowalski, R.M., 2016. Cyberbullying matters: Examining the incremental impact of cyberbullying on outcomes over and above traditional bullying in North America. In Cyberbullying across the globe (pp. 117-130). Springer, Cham.

González-Cabrera, J., Calvete, E., León-Mejía, A., Pérez-Sancho, C. and Peinado, J.M., 2017. Relationship between cyberbullying roles, cortisol secretion and psychological stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, pp.153-160.

González-Cabrera, J., León-Mejía, A., Beranuy, M., Gutiérrez-Ortega, M., Álvarez-Bardón, A. and Machimbarrena, J.M., 2018. Relationship between cyberbullying and health-related quality of life in a sample of children and adolescents. Quality of life research, 27(10), pp.2609-2618.

Graham, R. and Wood Jr, F.R., 2019. Associations between cyberbullying victimization and deviant health risk behaviors. The Social Science Journal, 56(2), pp.183-188.

Gualdo, A.M.G., Hunter, S.C., Durkin, K., Arnaiz, P. and Maquilón, J.J., 2015. The emotional impact of cyberbullying: Differences in perceptions and experiences as a function of role. Computers & Education, 82, pp.228-235.

Hamm, M.P., Newton, A.S., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Sundar, P., Ennis, H., Scott, S.D. and Hartling, L., 2015. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: A scoping review of social media studies. JAMA pediatrics, 169(8), pp.770-777.

Hartas, D. ed., 2015. Educational research and inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hase, C.N., Goldberg, S.B., Smith, D., Stuck, A. and Campain, J., 2015. Impacts of traditional bullying and cyberbullying on the mental health of middle school and high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 52(6), pp.607-617.

Hellfeldt, K., López-Romero, L. and Andershed, H., 2020. Cyberbullying and psychological well-being in young adolescence: the potential protective mediation effects of social support from family, friends, and teachers. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(1), p.45.

Hellfeldt, K., López-Romero, L. and Andershed, H., 2020. Cyberbullying and psychological well-being in young adolescence: the potential protective mediation effects of social support from family, friends, and teachers. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(1), p.45.

Hemphill, S.A., Kotevski, A., Tollit, M., Smith, R., Herrenkohl, T.I., Toumbourou, J.W. and Catalano, R.F., 2012. Longitudinal predictors of cyber and traditional bullying perpetration in Australian secondary school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(1), pp.59-65.

Inoue, J.I., Ghosh, A., Chatterjee, A. and Chakrabarti, B.K., 2015. Measuring social inequality with quantitative methodology: analytical estimates and empirical data analysis by gini and k indices. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 429, pp.184-204.

Katzer, C., Fetchenhauer, D. and Belschak, F., 2009. Cyberbullying: Who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in Internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of media Psychology, 21(1), pp.25-36.

Keusch, F., 2015. Why do people participate in Web surveys? Applying survey participation theory to Internet survey data collection. Management review quarterly, 65(3), pp.183-216.

Kim, S., Colwell, S.R., Kata, A., Boyle, M.H. and Georgiades, K., 2018. Cyberbullying victimization and adolescent mental health: Evidence of differential effects by sex and mental health problem type. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(3), pp.661-672.

Kim, S., Kimber, M., Boyle, M.H. and Georgiades, K., 2019. Sex differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), pp.126-135.

Kumar, R., 2019. Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage Publications Limited.

Li, Q., 2010. Cyberbullying in high schools: A study of students' behaviors and beliefs about this new phenomenon. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(4), pp.372-392.

Machackova, H. and Görzig, A., 2015. Cyberbullying from a socio-ecological perspective. Media@ LSE Working Paper, 36, pp.1-37.

McCarthy, N., 2018. Infographic: Where Cyberbullying Is Most Prevalent. [online] Statista Infographics. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/chart/15926/the-share-of-parents-who-say-their-child-has-experienced-cyberbullying/> [Accessed 16 April 2020].

McCusker, K. and Gunaydin, S., 2015. Research using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods and choice based on the research. Perfusion, 30(7), pp.537-542.

Menesini, E. and Spiel, C. eds., 2013. Cyberbullying: Development, consequences, risk and protective factors. Psychology Press.

Menesini, E. and Spiel, C., 2012. Introduction: Cyberbullying: Development, consequences, risk and protective factors. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), pp.163-167.

Meter, D.J. and Bauman, S., 2018. Moral disengagement about cyberbullying and parental monitoring: Effects on traditional bullying and victimization via cyberbullying involvement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(3), pp.303-326.

Miller, K., 2016. Cyberbullying and its consequences: How cyberbullying is contorting the minds of victims and bullies alike, and the law's limited available redress. S. Cal. Interdisc. LJ, 26, p.379.

Mishna, F., McInroy, L.B., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Bhole, P., Van Wert, M., Schwan, K., Birze, A., Daciuk, J., Beran, T., Craig, W. and Pepler, D.J., 2016. Prevalence, motivations, and social, mental health and health consequences of cyberbullying among school-aged children and youth: protocol of a longitudinal and multi-perspective mixed method study. JMIR research protocols, 5(2), p.e83.

Muhonen, T., Jönsson, S. and Bäckström, M., 2017. Consequences of cyberbullying behaviour in working life. International journal of workplace health management.

Navarro, R., Ruiz-Oliva, R., Larrañaga, E. and Yubero, S., 2015. The impact of cyberbullying and social bullying on optimism, global and school-related happiness and life satisfaction among 10-12-year-old schoolchildren. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 10(1), pp.15-36.

Navarro, R., Yubero, S. and Larrañaga, E., 2015. Psychosocial risk factors for involvement in bullying behaviors: Empirical comparison between cyberbullying and social bullying victims and bullies. School Mental Health, 7(4), pp.235-248.

Neuendorf, K.A., 2016. The content analysis guidebook. sage.

Nixon, C.L., 2014. Current perspectives: the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 5, p.143.

Palermiti, A.L., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M.G. and Costabile, A., 2017. Cyberbullying and self-esteem: An Italian study. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, pp.136-141.

Pandey, J., 2019. Deductive approach to content analysis. In Qualitative Techniques for Workplace Data Analysis (pp. 145-169). IGI Global.

Patchin, J. and Hinduja, S., 2016. Summary Of Our Cyberbullying Research (2004-2016). [Online] Cyberbullying Research Center. Available at: <http://cyberbullying.org/summary-of-our-cyberbullying-research> [Accessed 15 April 2020].

Patchin, J., 2016. New National Bullying And Cyberbullying Statistics. [Online] Cyberbullying Research Center. Available at: <https://cyberbullying.org/new-national-bullying-cyberbullying-data> [Accessed 15 April 2020].

Patchin, J.W. and Hinduja, S., 2015. Measuring cyberbullying: Implications for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, pp.69-74.

Pingault, J.B. and Schoeler, T., 2017. Assessing the consequences of cyberbullying on mental health. Nature human behaviour, 1(11), pp.775-777.

Routledge.Heiman, T., Olenik-Shemesh, D. and Eden, S., 2015. Cyberbullying involvement among students with ADHD: Relation to loneliness, self-efficacy and social support. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(1), pp.15-29.

Ryan, G., 2018. Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse researcher, 25(4), pp.41-49.

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. and Hamilton, H.A., 2015. Social networking sites and mental health problems in adolescents: The mediating role of cyberbullying victimization. European Psychiatry, 30(8), pp.1021-1027.

Selkie, E.M., Kota, R., Chan, Y.F. and Moreno, M., 2015. Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students: a multisite study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(2), pp.79-86.

Shin, N. and Ahn, H., 2015. Factors affecting adolescents' involvement in cyberbullying: what divides the 20% from the 80%?. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(7), pp.393-399.

Skilbred-Fjeld, S., Reme, S.E. and Mossige, S., 2020. Cyberbullying involvement and mental health problems among late adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(1).

Slonje, R., Smith, P.K. and Frisén, A., 2012. Processes of cyberbullying, and feelings of remorse by bullies: A pilot study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), pp.244-259.

Smith, P.K., 2012. Cyberbullying and cyber aggression. In Handbook of school violence and school safety (pp. 111-121). Routledge.

Sourander, A., Klomek, A.B., Ikonen, M., Lindroos, J., Luntamo, T., Koskelainen, M., Ristkari, T. and Helenius, H., 2010. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(7), pp.720-728.

Spears, B.A., Taddeo, C.M., Daly, A.L., Stretton, A. and Karklins, L.T., 2015. Cyberbullying, help-seeking and mental health in young Australians: Implications for public health. International journal of public health, 60(2), pp.219-226.

Statista. 2015. Cyber Bullying: Consequences For Young People 2015 | Statista. [online] Available at: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/765105/consequences-of-the-cyberbullying-in-the-young-boys-spanish-people/> [Accessed 16 April 2020].

Thomas, J.A., 2015. Using unstructured diaries for primary data collection. Nurse researcher, 22(5).

Varghese, M.E. and Pistole, M.C., 2017. College student cyberbullying: Self‐esteem, depression, loneliness, and attachment. Journal of College Counseling, 20(1), pp.7-21.

Waasdorp, T.E. and Bradshaw, C.P., 2015. The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), pp.483-488.

Waasdorp, T.E. and Bradshaw, C.P., 2015. The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), pp.483-488.

Wachs, S., Bilz, L., Fischer, S.M. and Wright, M.F., 2017. Do emotional components of alexithymia mediate the interplay between cyberbullying victimization and perpetration?. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(12), p.1530.

Wachs, S., Jiskrova, G.K., Vazsonyi, A.T., Wolf, K.D. and Junger, M., 2016. A cross-national study of direct and indirect effects of cyberbullying on cybergrooming victimization via self-esteem. Psicologia educativa, 22(1), pp.61-70.

Wegge, D., Vandebosch, H., Eggermont, S. and Pabian, S., 2016. Popularity through online harm: The longitudinal associations between cyberbullying and sociometric status in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(1), pp.86-107.

Whittaker, E. and Kowalski, R.M., 2015. Cyberbullying via social media. Journal of school violence, 14(1), pp.11-29.

Wigderson, S. and Lynch, M., 2013. Cyber-and traditional peer victimization: Unique relationships with adolescent well-being. Psychology of Violence, 3(4), p.297.

Wolke, D., Lee, K. and Guy, A., 2017. Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup?. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 26(8), pp.899-908.

Wright, M.F., Harper, B.D. and Wachs, S., 2019. The associations between cyberbullying and callous-unemotional traits among adolescents: The moderating effect of online disinhibition. Personality and individual differences, 140, pp.41-45.

Zaborskis, A., Ilionsky, G., Tesler, R. and Heinz, A., 2018. The association between cyberbullying, school bullying, and suicidality among adolescents. Crisis.

Zezulka, L.A. and Seigfried-Spellar, K., 2016. Differentiating cyberbullies and internet trolls by personality characteristics and self-esteem.

Zsila, Á., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M.D. and Demetrovics, Z., 2019. Gender differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and perpetration: the role of anger rumination and traditional bullying experiences. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(5), pp.1252-1267.

Appendix

Systematic LR Matrix

S. No. | Citation | Qualitative | Quantitative | Bullying and Cyberbullying | Factors for cyber involvement | Impact of Cyberbullying Mental Health of Adolescents |

| 1 | Navarro, Yubero and Larrañaga (2015) | X | X | |||

| 2 | Zaborskis et al. (2018) | X | X | |||

| 3 | Aricak and Ozbay (2016) | X | X | |||

| 4 | González-Cabrera et al. (2017) | X | X | |||

| 5 | Patchin (2016) | X | X | |||

| 6 | Fahy et al. (2016) | X | X | |||

| 7 | Zsila et al. (2019) | X | X | |||

| 8 | Wegge et al. (2016) | X | X | |||

| 9 | González-Cabrera et al. (2018) | X | X | |||

| 10 | Kim et al. (2019) | X | X | X | ||

| 11 | Coyne et al. (2017) | X | X | X | ||

| 12 | Wright, Harper and Wachs (2019) | X | X | |||

| 13 | Hase et al. (2015) | X | X | |||

| 14 | Waasdorp and Bradshaw, 2015) | X | X | |||

| 15 | Wachs et al. (2017) | X | X | |||

| 16 | Del Rey et al. (2016) | X | X | X | ||

| 18 | Graham and Wood Jr (2019) | X | X | |||

| 19 | Machackova and Görzig (2015) | X | X | X | ||

| 20 | Cowie (2013) | X | X | |||

| 21 | Li (2010) | X | X | |||

| 22 | Betts, Spenser and Gardner(2017) | X | X | |||

| 23 | Bevilacqua et al. (2017) | X | X | |||

| 24 | Hellfeldt, López-Romero and Andershed (2020) | X | X | |||

| 25 | Routledge.Heiman, Olenik-Shemesh and Eden (2015) | X | X | |||

| 26 | Nixon (2014) | X | X | |||

| 27 | Gualdo et al. (2015) | X | X | |||

| 28 | Navarro et al. (2015) | X | X | |||

| 20 | Albdour et al. (2019) | X | X | |||

| 30 | Muhonen, Jönsson and Bäckström (2017) | X | X | |||

| 31 | Gualdo et al. (2018) | X | X | |||

| 32 | Meter and Bauman (2018) | X | X | |||

| 33 | Menesini and Spiel (2013) | X | X | X | ||

| 34 | Miller (2016) | X | X | |||

| 35 | McCarthy (2018) | X | X | |||

| 36 | Jönsson and Bäckström (2017) | X | X | |||

| 37 | Pingault and Schoeler (2017) | X | X | |||

| 38 | Spears et al. (2015) | X | X | |||

| 39 | Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton (2015) | X | X | X | ||

| 40 | Brewer and Kersla (2015) | X | X | |||

| 41 | Varghese and Pistole (2017) | X | X | |||

| 42 | Zezulka and Seigfried-Spellar (2016) | X | X | |||

| 43 | Selkie et al. (2015) | X | X | |||

| 44 | Giumetti and Kowalski (2016) | X | X | X | ||

| 45 | Palermiti et al. (2017) | X | X | X | ||

| 46 | Extremera et al. (2018) | X | X | |||

| 47 | Mishna et al. (2016) | X | X |

Get an Immediate Response

Discuss your custom requirements with our writers

Get 3+ Free Custom Topics within 24 hours;

Free Online Plagiarism Checker For Students

We will email you the report within 24 hours.

Upload your file for free plagiarism