Dissertation Interview Questions | Everything You Need To Know

August 29, 2024The Alchemy Of Found Objects

February 18, 2025 Download PDF File

Download PDF File

Abstract

This research project delves into the nuanced complexities of Spain's management of colonial history, highlighting the profound impact of regional historical and political factors. Initially aimed at a national-level examination, the project evolved to reveal intricate dynamics within Spain's seventeen autonomous communities, with a shared motivation to reclaim and preserve historical memory. Both Andalucía and Catalonia, despite distinct regional histories, overlook Native Latin American perspectives in their cultural institutions, perpetuating a one-dimensional colonial narrative.

Review Top Dissertation Examples in 2025

The project seeks to achieve several goals. Firstly, it aims to underscore the regional complexities in Spain's handling of colonial history. Secondly, it highlights the neglect of indigenous voices, showing that while both regions disregard these perspectives, they interpret and convey their nationalistic histories uniquely, shaped by their distinct contexts.

Moreover, the project recognises the need for alternative representation and proposes innovative approaches fuelled on the critique on case studies from Andalucía and Catalonia, compared with a New York exhibition. These comparisons provide valuable insights into representing colonial viewpoints within Spanish cultural institutions, drawing from substantial advancements in research made in the United States.

In summary, this research project navigates Spain's colonial history within its autonomous communities, emphasising the neglect of Native Latin American perspectives and the importance of preserving historical memory. By exploring regional nuances and drawing international comparisons, the project aims to offer fresh insights and strategies for enriching the portrayal of colonial history in Spanish cultural institutions.

Introduction

Spain is formed by seventeen autonomous communities, and recognises four official languages. The “strong geographical and cultural diversity within the country, together with other historical and political factors, have translated into the existence of numerous sub-state parties of a regionalist or nationalist nature.” Spanish cultural institutions are highly politicised, and used to portray certain historical perspectives and narratives. As David Carr states “Every person is, by definition, a part of a culture and so constituent of the institutions it sustains. Consequently, we should each consider these places to mirror in some way the human experience as we can know it, or as we might wish to understand it.”

This research project will analyse two case studies; two cultural institutions within different geographical, and cultural parts of Spain; Andalucía and Catalonia. It will investigate how each institution interprets and portrays Spanish colonial history with an aim to underpin why these regions ‘wish to understand’ the history through a different lens. In other words, how does each regions’ unique history impact the narrative of Spain’s collective colonial history.

Current literature investigating the correlation between Spain’s colonial memory and history within their cultural institutions, with regional nationalism as an ulterior motive is limited, however academic; Jean Monsod raises the argument that “history and memory are often considered as each other’s antithesis. But at certain critical junctures such as the end of colonisation, both become avenues for a return to the past, if only to determine how earlier times have shaped the present.” With an absence of literature discussing these challenging colonial topics in Spain, it can highlight the underlying neglect of historical responsibility, which is reflected in Spain’s cultural institutions.

Learn How To Do a Literature Review

Joseba Gabilondo provides evidence on why and how European countries my handle their colonial history through a sanitised lens. He delves into the concept of fundamentalism as a means of explaining the neoliberal shift in European states. This shift involves a reimagining of these states in neo-nationalist and imperialist terms, often characterised by a forgetting of their colonial past.

The author draws attention to a crucial aspect: the internal others within these European states become the focal point of racism and fundamentalism. This is exemplified by the rise of ultra-right politics in France under Le Pen and the xenophobia surrounding El Ejido in Spain. The author equates "fundamentalism" with neoliberalism, highlighting the ideological processes at play.

To provide a broader European context for this, the author cites French and German scandals. These scandals serve as a reflection of the emerging yet non-hegemonic nature of this new ideology. They reveal a collective desire or rejection that cannot be entirely embraced or renounced by the majority. These scandals are deeply intertwined with issues of memory and the past.

The text accentuates the elaborate relationship between historical memory, ideology, and the construction of identity within the European context, shedding light on the ways in which neoliberal fundamentalism influences historiographical discourse in Spain and beyond.

To further Gabilondo’s discourse on colonial fundamentalism in Europe and their handling of their colonial past, Gayatri Chakroavorty Spivak in Can the Subaltern Speak? addresses the systematic and structural limitations within society, which prevents marginalised groups from having agency over an unbiased and truthful representation and voice within society, which in turn affects how cultural institutions may seek to remember and portray indigenous voices and histories. As Graham Riach states: “It (Can the Subaltern speak?) sparked furious debate in the academic community about how intellectuals play a role in silencing subaltern voices. By speaking for subalterns, Spivak suggests, even well-meaning academics can do harm”. This is validated by academic writer Linda Tuhiwai, who describes that “the burden of history makes the positioning of an indigenous person as a researcher highly problematic.” To further exemplify this notion, she adds that “indigenous peoples have an “abhorrence and distrust of research.”

In Decolonising history, a Latin American perspective, the author explains that “the field of global history has been thriving for over two decades; however, unlike Europe, the United States, and Asia, which have witnessed a true “boom” in this area, there has been no such significant development in Latin America. In fact, there is even an attitude of rejection toward what many academics in the region consider an “Anglo-Saxon trend.” This argument can be used to further support Spivak’s perspectives on whether the subaltern actually have a voice within society, whilst simultaneously reflects what academic Tuhiwai describes as a ‘burden of history’ for indigenous peoples.

Spain’s contemporary history is especially complex, and it plays a vast role in the underrepresentation of its colonial history. It is a clear example that the systematic hegemony in Spain influences the narratives within their cultural institutions regarding colonialism.

Methodology

The chosen research methodology for this research entails in-person fieldwork at cultural exhibitions in Catalonia and Andalucía, Spain. This approach was selected to provide a first-hand experience and access to primary data sources. By physically visiting these exhibitions, I can engage directly with the curated materials, observe exhibition design, and gain a deeper understanding of how colonial history is portrayed. This immersive experience allows for a comprehensive analysis of the physical and visual aspects of the exhibitions. Additionally, fieldwork offers a contextual understanding of the regional dynamics at play in Catalonia and Andalucía, both of which have distinct historical, political, and cultural backgrounds influencing the representation of colonial history. The methodology also facilitates a comparative analysis between the two regions, highlighting regional disparities in the portrayal of this history. Furthermore, it allows for the observation of visitor engagement, adding a qualitative dimension to the research. Ethical considerations are integral to this methodology, enabling the evaluation of how these exhibitions address issues such as repatriation, indigenous perspectives, and the impact of colonialism on contemporary communities. In summary, in-person fieldwork serves as a robust and comprehensive method for examining the representation of colonial history in cultural institutions.

The research project initially set out to examine Spain's approach to managing its colonial history on a national level. However, as my research and fieldwork progressed, it became evident that the narratives surrounding this history were intricately linked to complex regional political and historical factors. These factors were underpinned by a shared motivation to reclaim and preserve historical memory. While both Andalucía and Catalonia share the common issue of neglecting Native Latin American perspectives and consequently depriving them of agency in cultural institutions, they each interpret and present distinct nationalistic historical narratives. These narratives are uniquely relevant to their respective regions. In essence, this research project seeks to achieve several objectives: To highlight regional complexities by acknowledging that Spain's management of colonial history is not uniform across the nation, emphasising the profound impact of regional historical and political intricacies. To exemplify the neglect of indigenous perspectives in both Andalucía and Catalonia, despite their regional disparities, share the common problem of overlooking Native Latin American viewpoints. This oversight perpetuates a multi-dimensional narrative of colonial history. Additionally, while both regions disregard indigenous voices, they interpret and convey their nationalistic histories in distinctive ways, shaped by their unique historical and political contexts. Finally, to explore alternative representation; the research project aims to propose innovative approaches for representing colonial perspectives within Spanish cultural institutions. It intends to draw insights from the two case studies in Andalucía and Catalonia, comparing them with an exhibition in the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. This comparison offers valuable lessons from the substantial advancements in research made in the United States, validated by academics G. De Lima and S. Schuster.

In summary, this research project delves deeply into the nuanced and region-specific complexities of Spain's handling of colonial history. It recognises the neglect of Native Latin American perspectives and underscores the significance of preserving historical memory. By drawing international comparisons, the project aspires to provide fresh insights and alternative strategies for representing colonial viewpoints within Spanish cultural institutions.

The Spanish Context

The trajectory of post-colonial Spain is a tapestry woven with historical intricacies and political transformations. As a nation that once wielded immense colonial power, Spain underwent a tumultuous journey in the 20th century that left deep-rooted marks on its socio-political landscape. The loss of colonies, left Spain in a national ‘depression’ , and in a state of insecurity and division. This is characterised by the essays of the famous 20th century Spanish traditionalist and philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset. In España Invertebrada (Invertebrate Spain) one can interpret his perspectives on Spain’s social, political and economic complexities within the post-colonial context. Ortega y Gasset places grand emphasis on where Spain failed to establish a central elite that will inspire the masses. As a solution, he writes about the necessity to unionise Spain. Ortega y Gasset presents Spain’s colonial history through a positive narrative, where he describes it as the ‘golden age’ of Spain, where all social classes, regional identities and political parties shared one common thing; the memory of empirical glory. However, the 20th century was a watershed era for Spain, characterised by significant shifts in power dynamics and political ideologies. The nation, which once held a vast global empire, saw its empirical dominion crumble, leaving it in a state of re-evaluation and introspection. Ortega y Gasset provides an insight into the post-colonial Spanish context in the turn of the 19th to 20th century, and the social instability which is validated by a contemporary 21st century historian, Simon Barton, who explains the failures of the Spanish Republic in reforming both the urban and rural working classes’ living and working conditions, led to a working class militancy. In addition, extremist political groups had begun to form which derived from “widespread disenchantment with parliamentary democracy”. Both sources concur with the notion of socio-political and economical divisions, eventually caused the eruption of the Spanish Civil War.

The twentieth century's legacy in post-colonial Spain is marked by the tensions between conservative traditionalism and progressive aspirations for democracy and modernisation. As Simon Barton describes it “a struggle between the Two Spains’ of progress and tradition, between anarchy and order”. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) stands as a pivotal moment in Spanish history. Francisco Franco's Nationalists triumphed over the Republican government, due to the overwhelming nationalistic support from European allies in Italy and Germany. This victory ushered in a decades-long fascist dictatorship that left Spain isolated from the international community, up until 1975 when Franco died along with his fascist Spain, de jure. However, the ghost of post-fascism continued to loom large in post-colonial Spain. His death in 1975 set the stage for a fragile transition to democracy, known as "La Transición" (The Transition) symbolised by a balance between maintaining stability and addressing historical injustices. The establishment of a constitutional monarchy, the reintegration of autonomous regions, and the acknowledgment of cultural diversity were fundamental components of this period. Despite its successes, the legacy of Franco's oppressive rule lingered, shaping the national discourse around historical memory and reckoning. Notwithstanding the reestablishment of democratic and liberal principles in Spain, the vestiges of fascism endure within Spanish society, thereby impeding its gradual process of reintegration into democratic ideals. Steps to address and change the narrative of Spanish historical and cultural heritage have not been made in order to restore vast historical justice to such a traumatic past, or as historian Paul Preston describes as a ‘Spanish holocaust’. For example, the negligence of historical reparations towards La Valle de los Caídos (The Valley of the Fallen), a controversial, grand monument which was built with the blood of enslaved forces that threatened the traditionalist Spain, whom died during its construction. For many Spanish citizens, the controversial heritage site is a “shrine to Francoism” and an “affront to the victims of Francoist repression and the country’s new democracy”. The Pacto del Silencio (Pact of Silence) in Spain, aimed at consigning the past to oblivion as a means to embrace the future , can be critically examined as a conduit through which the legacy and ideologies of Francoism endure within contemporary Spain.

The Dangers of Forgetting

Choosing to forget traumatic histories rather than confront them can give rise to a multitude of adverse outcomes. Firstly, it risks the recurrence of past errors, as the absence of comprehension and recognition of historical wrongs elevates the likelihood of similar events unfolding in the future. Moreover, it can perpetuate injustice by fostering a climate where accountability for perpetrators is lacking and justice for victims remains elusive, potentially nurturing a sense of impunity. For survivors, the failure to address past trauma can deepen psychological suffering, leaving enduring wounds on individuals and communities. Societies that decide to erase traumatic histories may find themselves ensnared in a state of collective amnesia, impeding empathy, understanding, and potentially fuelling division and strife. Simultaneously, the forfeiture of historical knowledge, an inevitable outcome of such forgetfulness, deprives societies of invaluable lessons for responsible and informed decision-making. Lastly, in certain instances, governmental or institutional encouragement of forgetfulness, as a tool to suppress dissent and maintain control, poses a threat to free expression and obstructs the progress of democratic principles. These adverse consequences underscore the vital significance of addressing traumatic histories as an essential step towards healing, enlightenment, and the nurturing of more educated and compassionate societies.

Racism and Prejudice in Spain

The presence of racism in Spain, though often overlooked, is an issue deserving of attention. Spain's colonial history left an imprint on its societal perceptions, contributing to deeply entrenched stereotypes and biases. The influx of immigrants from former colonies and other regions has led to the emergence of racism in various forms, ranging from xenophobic sentiments to structural discrimination. The Roma community, for instance, has been disproportionately marginalised and subjected to social exclusion. In recent years, advocacy groups and civil society have worked to spotlight and address these issues, prompting conversations about systemic racism and the need for inclusive policies.

Spain's journey towards post-colonialism and political transformation has been marked by a complex interplay of historical inheritance and evolving ideologies. The nation's transition from a colonial power to a modern European democracy required confronting its own dark past, engaging in a process of reconciliation, and striving to overcome deeply rooted biases. While progress has undoubtedly been made, the echoes of history and the challenges of the present continue to shape the nation's path.

In conclusion, the legacy of the 20th century and the shadow of post-fascism have left their marks. The nation's historical memory, shaped by colonial exploits and the Franco era, intertwines with contemporary challenges, including racism and social inequality. As Spain moves forward, it must respond to these complexities, fostering an inclusive society that acknowledges its historical baggage while paving the way for a more equitable future. The ongoing dialogue about its colonial legacy and the impact of post-fascism highlights the nation's resilience in navigating the complicated fragments of its own history.

Catalan and Andalusian Political Contexts

Catalunya and Andalucía, two distinct regions within Spain, both maintaining unique historical trajectories and identities that give rise to contrasting political contexts. These differences profoundly influence their perspectives on colonialism, historical representation, and their contemporary political stances. Analysing the intricate relationship of history, identity, and politics in Catalunya and Andalucía provides insight into the complexities of regional dynamics within Spain.

Catalunya, situated in the north-eastern corner of Spain, has long maintained a distinct cultural and linguistic identity. In the year 1150, the Count of Barcelona entered into matrimony with the Princess of Aragon, an event that marked the merging of these two kingdoms and the conclusion of Catalonia's separate identity. For the ensuing nine centuries, Catalonia remained a part of Spain, resiliently preserving its language, culture, and historical heritage. Each 11th of September, Catalans commemorate their National Day, known as La Diada Nacional de Catalunya, reflecting on distant occurrences that remain deeply etched in their collective memory. This anniversary is tinged with mixed emotions, primarily evoking the recollection of the loss of territorial autonomy and constitutional legacy. It all began when Philip V, the Bourbon claimant to the Spanish throne, concluded the War of Spanish Succession in 1714 by concluding a 14-month siege of Barcelona with a final, ruthless assault on the city.

The era of Catalan oppression under General Francisco Franco's dictatorship (1939-1975) remains vividly etched in the memory of the Catalan community. Those born in Catalonia during this period were not permitted to use their language or even bear a Catalan name. Following the fall of the dictatorship and the restoration of democracy, Catalonia grappled with deconstructing institutional biases against them. Although they regained regional autonomy, in the 21st century, they find themselves constrained from exercising their right to democratically vote for independence. The attempted referendum in 2017 was met with violent suppression, resulting in severe and lasting injuries for some Catalan individuals. Unpardonably, the Spanish Police even targeted the elderly, who were more vulnerable and wished to participate in the vote, exhibiting a level of brutality reminiscent of earlier forms of fascist repression and violence in Spanish history.

In contrast, Andalucía, situated in the southern part of Spain, holds a history marked by diverse cultural influences, including Moorish, Roman, and Phoenician. These layers of historical legacies contribute to Andalucía's vibrant cultural mixture. However, the region also experienced economic challenges and underdevelopment, which have contributed to a distinct political narrative. While Andalucía was not an independent entity like Catalonia, its historical experiences have shaped its political priorities. The region's political stance is often focused on economic development, social justice, and combating inequalities. The legacy of underrepresentation and socio-economic struggles has influenced how Andalucía views issues of colonialism and historical representation, with a lens that seeks to address present-day disparities more urgently.

Under the rule of General Francisco Franco, the region of Andalucía in Spain, like many other regions, experienced the imprint of fascism on its culture, history, and memory. Franco's regime sought to impose a uniform Spanish identity and suppress regional identities, including Andalucía's distinctive culture. Indifferently to Catalonia, where culture was oppressed, one of the strategies employed by the regime to achieve national cohesion was the appropriation of Andalusian culture and traditions, including the vibrant expressions of flamenco dance and music, which were leveraged to bolster the flourishing tourism industry. In light of the reality, Spanish flamenco and dance has a unique history; evolving from the Spanish Roman Gypsy community, with ancient musical and dance influences dating back to Moorish Spain. Franco's regime controlled historical narratives to glorify Spain's imperial past, while downplaying or ignoring aspects of its history that didn't fit the regime's ideology; ie, the Gypsy or Arabic past. This selective memory impacted how historical events, such as the diversity in Andalusian historical heritage, were remembered and taught in Andalucía.

Colonial Perspectives and Historical Representations in Spain

The post-colonial period in Spain has brought about significant changes in the country's political and social dynamics, which in turn have influenced the way historical events are represented in Spanish museums. This is evident in curatorial decisions, narrative structures, and the inclusion or exclusion of specific historical events and voices within these institutions. The legacy of colonialism, the Franco regime, and the quest for cultural diversity have all played a role in shaping the way history is portrayed in Spanish museums. Curators are challenged to balance the celebration of cultural exchange with a critical examination of the negative consequences of colonialism.

The narrative presented by museums, irrespective of their portrayal, frequently reveals the intrinsic contradictions and lingering colonial influences at the heart of what is commonly recognised as ‘Spanish culture’. Authors, Esther Gabara and Isabel Adey note the “Spaniards enjoy Andean potatoes in their tortillas and Mayan chocolate with their churros, without savouring the American bitterness that is their basic ingredient”.

The authors of this academic essay provide insight to the significance of the physical outdoor space of Madrid, and how colonial history is remembered outside of the museum space. They explain that, to reach the Prado (Colonial Museum in Madrid) from the eastern part of the city, one must cross the Buen Retiro Park, a green expanse that began taking shape when the colonial enterprise was in full swing. While strolling through the “meadows” (prados) from which Spain’s preeminent art institution derives its name, visitors follow the path along Paseo de Uruguay, veer right onto Avenida de Cuba, and subsequently turn left onto Paseo del Paraguay. Authors note that it is intriguing that, although these promenades and avenues bear the names of Latin American countries, there is a conspicuous absence of explicit references or depictions of these former colonies upon arriving at the museum itself. It is suggested that this absence is quite remarkable, especially considering that the abundance of natural and cultural riches from these colonies substantially underwrote the masterpieces showcased within the Prado. Furthermore, the essay argues that, Museums, such as the Prado, regularly reorganise artworks from their permanent collections for display in their exhibition spaces. However, what truly stands out is the stark absence of acknowledgment of the colonial project, especially within a museum celebrated for its compilation of art created during the peak of Spanish colonialism in the Americas. This situation highlights the intricate and frequently conflicting essence of ‘Spanish culture,’ which is infused with the echoes of colonialism. It underscores the imperative need for a thorough examination of the historical and cultural consequences embedded within this multifaceted narrative. Authors, Esther and Isabel go on to describe the curatorial decisions of colonialism as (an) “invisibility of the Americas in the Prado as a learned blindness”.

The same can be compared to Catalunya. When it comes to perspectives on colonialism and historical representation, Catalunya's historical memory is of cultural oppression. This patriotism of its history and culture, has now fuelled a desire for representation within the museum context. Concerning colonial memory, mirroring the spatial observations made by authors in Madrid, Barcelona's port still hosts an imposing monument of Columbus, resolutely gesturing toward the Americas. Additionally, drawing upon a past visit to the Museu Etnológic de Barcelona, which I visited in Spring 2023, I reflected on the curatorial decisions in the exhibition of ‘Barcelona cultures’. One of the main critiques of the exhibition, was that in the main exhibition space, objects relating to traditional Catalan culture were exhibited, which draws far more emphasis on a ‘preferred’ culture to be shown. Other colonial objects throughout the exhibition, where often grouped together in a manner that separated these cultures to the Catalan one. Similar to the essay of the Museum, Prado in Madrid, there was a clear acknowledgement of colonial history and culture, however the curatorial decisions had seemingly neglected to integrate and interweave the historical narratives together.

Andalucía's history has led to a more nuanced approach to colonialism and historical representation. While it acknowledges the impacts of colonisation, through exhibitions that are organised by the Latin American embassies, Spanish owned institutions often glorifies their empirical history, which is reminiscent of the appropriated Andalusian culture for tourism, which ‘unified’ Spain during the fascist dictatorship. Likewise in Sevilla, there are monuments around the city which hold vast colonial significance, and act as a societal insight into Spanish collective memory of its empire, and subsequent contemporary perspectives on it. Furthermore, it suggests that it may not be a Spanish priority to revisit colonial history and reinterpret it through an alternative lens. This is a matter I will expand on within my case studies. However, it is vital to mention this argument within more generalised context of Spanish colonial representation.

Having observed the curatorial decisions in the Barcelona exhibition, and having been to both Barcelona and Seville to witness the colonial memory entrenched in the physical spaces of the cities, coupled with the research on the Prado museum, the post-Franco transition to democracy ideology of ‘forgetting’ (Pacto de Silencio) came to my attention. Is simply acknowledging colonialism an appropriate perspective to have in a contemporary society, where visitors may seek for an unsanitised narrative?

In conclusion, post-colonial Spain's political and social dynamics have left a lasting impact on the way history is represented in Spanish museums. The complexities of Spain's colonial past, the legacy of the Franco regime, the pursuit of cultural diversity, and ongoing debates about regional autonomy all influence curatorial decisions, narrative structures, and the inclusion or exclusion of historical events and voices. As Spain continues to grapple with its post-colonial identity, museums play a vital role in shaping the nation's historical consciousness and fostering a more inclusive understanding of its past.

Case Study Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona

The Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona (The Ethnologic Museum of Cultures of Barcelona) offers a compelling case study that highlights the challenges of maintaining an impartial, ethnographic approach to history while navigating the intricacies of regional politics and historical contexts. During my visit to this museum in the spring of 2023, it became evident that this cultural institution reflects the broader conundrum faced by museums in Catalonia, wherein they must navigate and explore an array of cultural narratives under in one exhibition and institution.

At the heart of my analysis lies the contention that, despite its commendable endeavour to celebrate diverse cultures and preserve cultural heritage, the museum's ethnological approach inadvertently exposes an undercurrent of ethnocentrism. This issue becomes palpable when examining how objects are arranged and grouped within the exhibition. While it remains imperative for Catalonia to engage in discussions about its historical traumas and cherish its cultural heritage, there's a discernible tendency within the museum to present Catalonia's colonial history through a sanitized and idealised lens.

However, before delving into the specifics of particular objects within the exhibition, it's crucial to establish the foundational observations and reflections that framed my approach. This preliminary understanding lays the groundwork for a comprehensive analysis of how history is imparted through these objects, offering insight into whether these objects collectively construct a coherent narrative or, conversely, subtly harbour political and historical agendas.

My initial impressions upon entering the museum were marked by a sense of bewilderment. The vast array of cultural objects from diverse corners of the world seemed to lack a cohesive narrative thread. While the museum's brochure articulated its intent to celebrate the diverse cultures that have contributed to the making of the city and region over the centuries, the visitor experience felt less like a celebration and more like an oversight of the intricacies of these diverse cultures and their entwined histories.

This feeling was particularly pronounced when examining the artifacts of colonial nature on display. Questions about their provenance and the ethical considerations surrounding their exhibition began to surface. Notably, the spatial layout of the exhibition appeared to validate these initial impressions. The primary exhibition space, prominently showcasing traditional Catalan cultural objects from the Middle Ages to the present day, seemed disconnected from the colonial artifacts. This physical separation symbolically accentuated the notion of 'the Other,' reinforcing the subtle complexity of the museum's narrative.

Additionally, it is imperative to underline the undercurrents of Marxist historiography that subtly influence the exhibition at the Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona. The Spanish Civil War, a watershed moment in Catalan collective memory, holds a central place in this influence. Catalonia, being the epicentre of the Republican movement during the war, hosted numerous communists, including Russian allies. This historical backdrop is crucial to understanding the selection of objects in the exhibition.

Marxist historiography, rooted in Karl Marx's critique of positivism, emerges as a compelling lens through which to view the exhibition. During the 19th century, history had a marginal role in comprehending human society's past and present. This perspective evolved as a response to the limitations of hierarchical social structures and found resonance in various historical contexts, such as the French Revolution, the rise of the working class, and movements in Western colonies like Cuba and Central America. Notably, the objects related to Catalonia's working classes and peasantry within the exhibition can be seen as emblematic of centuries of oppression at the hands of the Castilian monarchy.

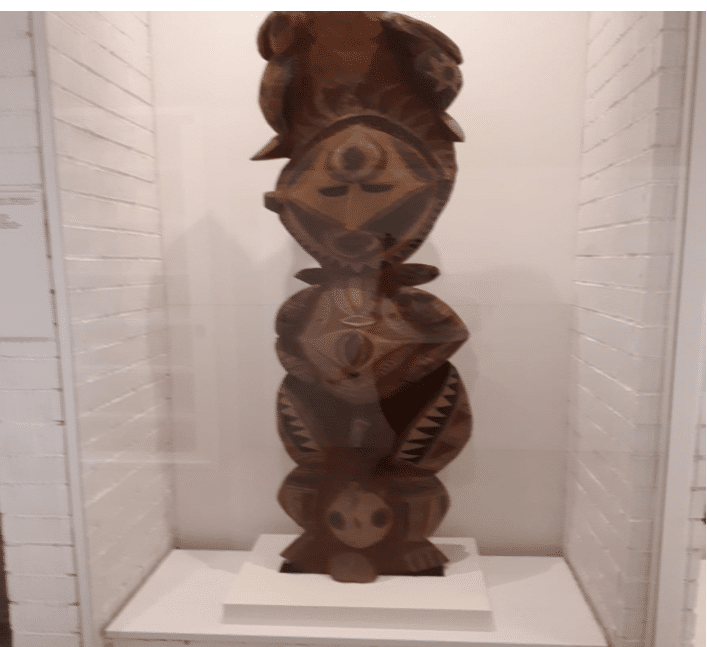

However, a critical dimension of the museum's collection lies in the presence of tribal artifacts with spiritual significance. These objects likely have complex histories, often involving means such as looting during the slave trade and colonialism or acquisition without full awareness of their implications. Notably, the display of these objects sparks crucial debates surrounding the repatriation of stolen artifacts.

In the Ethnologic Museum of Cultures of Barcelona, these objects find their place in the 'reserve collection,' distinct from the central exhibition focused on Catalan culture. This arrangement, while potentially a pragmatic organisational choice, carries deeper implications. It hints at the concept of the Other , a concept expounded by Reesa Greenberg, which revolves around recognising the existence of diverse cultural narratives within a shared space. While the museum's intention is to showcase Barcelona's cultural diversity, the separation of these objects raises questions about the sincerity of this portrayal.

Figure 2: Anna Albuixech, “Tribal Sculpture”, 2023, Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona

Figure 3: Anna Albuixech, “African Sculptures”, 2023, Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona

As Pamela McClusky says “what on earth is this, why is it here, how do I make sense of it?” were my initial thoughts upon observing the tribal figures above. With the absence of textual narrative to go with these specific objects, the more I realised there was a lack of emphasis on exploring the diverse ‘cultures’ in Barcelona, and more to do with ticking certain inclusivity boxes. Furthermore, I wondered how tribal African figures, I assumed that had been acquired through problematic means, were representative of contemporary cultures of Barcelona. I reflected on how any Spaniard of African descent could possibly view these objects as representative of their identity, and culture within a Spanish context, without bringing up traumatic colonial narratives. Additionally, the lack of textual analysis, which could have contextualised the placement of these objects within the exhibition, further promoted this sense of the othering, and additionally emphasised the preferred ‘culture’ within the exhibition to be focusing on; the Catalan one, where an range of textual narratives were offered. I wanted to know where these objects had come from, and what they meant, as I struggled to appreciate their significance, which ultimately highlighted the failure of this institutions’ ethical obligations to address forgotten histories, by creating more agency and voice to citizens whom had been directly affected by colonialism, or neo-colonialism. As previously mentioned, it reaffirmed this idea of the pact of silence. If silence is a method used in Spain to see past traumatic histories, it is removing historical agency to those who righteously deserve to have a voice in cultural and public spaces. Taking away agency, takes away the power of knowledge . Furthermore, to group black culture in this context undermines their journey past the slave trade, and integration into western culture. Therefore the display of these objects directly emit racial connotations. To further this idea, one of the statues in figure: appears to be wearing a small white cloth to cover its’ intimate parts, which is reminiscent of how black slaves have been depicted throughout history, wearing nothing but a cloth to cover.

In a wider Spanish colonial context, “subduing and narrowing the history of slavery is instrumental in the reproduction of national ideologies of mestizaje in Afro-Latin America” In the broader context of Spanish colonial history, the deliberate suppression and selective framing of the history of slavery serve as crucial mechanisms for perpetuating and reinforcing the national ideologies of mestizaje within Afro-Latin America. Mestizaje, which refers to the blending or mixing of different racial and ethnic groups, has been a central theme in the construction of national identities across Latin America. While mestizaje often highlights the fusion of Indigenous and European cultures, its portrayal tends to marginalize or even erase the significant contributions and experiences of Afro-Latin Americans, particularly those who are descendants of enslaved Africans.

The subduing of the history of slavery involves minimising its extent, brutality, and enduring impact on Afro-Latin American communities. By downplaying the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, the brutal conditions on plantations, and the systemic dehumanisation of enslaved people, national narratives can create an idealised image of mestizaje that conveniently sidesteps the uncomfortable truths of racial oppression and exploitation.

Furthermore, narrowing the historical focus serves to diminish the agency and resilience of Afro-Latin Americans throughout history. It reduces their multifaceted contributions to the development of Latin American societies, including their influence on art, music, religion, and culture. By narrowing the narrative, the broader public is denied a comprehensive understanding of the richness and diversity of Afro-Latin American heritage.

This deliberate narrowing of focus also reinforces a hierarchical racial order. By centring mestizaje as the dominant narrative, it reinforces the notion that racial mixing with European ancestry is the most desirable and legitimate path to national belonging. This can marginalise those who do not fit this ideal, particularly Afro-Latin Americans, and perpetuate racial hierarchies that continue to impact social and economic opportunities in contemporary Latin American societies. During the colonial era, the Spanish empire would “map out” the central ethnicities around the colonised land, and would also have a “casta system” , which “sought to determine access to certain rights, professions, and institutions on the basis of ancestry, also accounted for Africans, most of whom were brought to the New World as slaves by the Spanish”. Evidently, the Spanish were in the “top of the group….others were ranked below based on their percentage of Spanish blood. Th child of a Spaniard and indigenous person…was called a mestizo, while the child of a mestizo and a Spaniard was called a castizo” .

In summary, within the context of Spanish colonial history and its legacy in Afro-Latin America, subduing and narrowing the history of slavery is a powerful tool for constructing and preserving national ideologies of mestizaje. This process not only obscures the harsh realities of slavery but also perpetuates racial hierarchies and marginalises Afro-Latin American voices and contributions within the broader narrative of national identity.

In essence, the Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona presents a complex case study that vividly illustrates the convoluted challenges of decolonising an impartial historical perspective while operating within a politically charged regional context. Moreover, it sheds light on the ethical dilemmas inherent in the display of colonial artifacts within the context of a modern ethnological museum. This case study offers valuable insights into the complexities of historical representation within ethnographic museums and underscores the ongoing relevance of these conversations within cultural institutions worldwide.

Chapter 3 - Case Study Sevilla

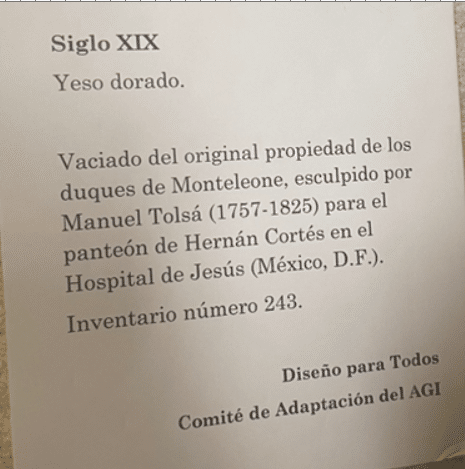

Figure 4: Anna Albuixech: “Busto de Hernán Cortés”, 2023, Archivos Generales de las Indias, Seville

Figure 5: Anna Albuixech: “Busto de Hernán Cortés text”, 2023, Archivos Generales de las Indias, Seville

Chapter 4: Introduction to the First Case Study Chapter

In the halls of the Archive of the Indies Museum, a collection of historical artifacts awaits museological and historical reflection. In this initial case study chapter, I will delve into the core of this esteemed institution with a dedicated objective: to meticulously analyse selected objects from its repository. These artifacts, preserved and curated, transcend their material existence to offer insights into an era marked by exploration, and will further my research in studying the regional history and politics which interplay with the production of Spain’s empirical history and memory.

The Archive of the Indies, situated in the historic city of Seville, Spain, has earned a reputation as a curator of colonial memory, the location as well as the institution; having been

a city used for colonial trade. Additionally, the institutions’ holdings comprise documents and artifacts that narrate the encounters between civilisations during the age of exploration and colonisation.

I will explore the intricacies of these objects, which I hope will evidence Spanish cultural, political and historical intricacies, which binds the representation and treatment of Spain's colonial history to the broader global narrative. I will be considering various contexts within history, their roles in facilitating cultural exchanges, and their implications for our comprehension of enduring colonial legacies. Through this analysis, I will aim to illuminate the complex narratives these objects convey—narratives that have indelibly shaped the course of human history.

Firstly, I will shed some light on my overall experience and initial thoughts as I walked around the institution in order to give context to the object I will be analysing as part of this case study. After having digested the collection on display at the archives, I felt rather disappointed with the sheer lack of indigenous voice and narrative included in the exhibition. Walking around the displays, it initially struck me as a shrine to the colonists, with paintings of every South American generals hanging from high ceilings around the buildings, along with objects and paintings of Conquistadors, when they discovered America. Marginalised groups were excluded from the narrative, and there were no artefacts or objects of historical significance relating to the story of colonialism depicted through their lens. This instantly reminded me of the Post-Francoist feeling of pride towards their colonial history.

Upon entering the Archives Museum, I turned to my left and instantaneously walked over to the corner of the room, where an illuminating gold object had caught my attention. It was on a tall plinth, and the object appeared rather important and significant. As I approached, I soon found out that it was the bust of explorer; Hernán Cortés. Hernán Cortés stands as a pivotal figure in Spain's colonial conquest and expansion in the Americas. His conquest of the Aztec Empire, Mexico in the early 16th century reshaped the course of history, marking a defining moment in Spanish colonialism. The bust had been labelled as an exact replica of an original bust created to be homed in The Hospital of Jesus, in Mexico between 1787-1825. The original bust is now being displayed in a Mexican museum of colonial history.

Upon close observation of the object in question, I reflected on the uncanny resemblance the 19th century object had, with similar busts of the Roman Empire dating back to the Neolithic period. The bust of Hernán Cortes is depicted wearing a toga, and the intricate curls in his hair, and the shape of his eyes are reminiscent of the busts created to monumentalise the Roman figures and Gods. The style in which this bust has been made, mirrors the grandeur of the Roman empire and therefore the Roman conquest, further monumentalising the Spanish empire, by almost offering a comparison to the viewer. Additionally, it romanticises European conquests, which arguably can be viewed to have a Eurocentric complex.

The material of the bust is described as ‘yeso dorado’, which is plastered gold. The decision to immortalise Cortés in gold is laden with symbolism. Furthermore, to create a replica a century after drives this idea of his immortality and popularity to be involved in narrating colonial history. The original, which was made entirely out of gold, a coveted and esteemed resource in the Americas, was central to Spain's colonial ambitions. It symbolises not only the wealth extracted from the New World but also the power dynamics of the colonial era. The use of gold to represent Cortés underscores the material and economic motivations behind Spain's colonial ventures, inviting reflection on the human and environmental costs incurred during the pursuit of these riches.

The object serves as a tangible historical representation of colonial attitudes and sentiments of the time it was created. To have such a fine object be crafted so intricately and meticulously in the 18th century, made from resources exploited from the land, proves the lasting legacy of this Conquistador, a century after Mexico was conquered. It is a symbol of power, importance and wealth, all of which are colonial legacies that contemporary historians are working towards to dismantle in order to reframe historical memory of colonialism through a non-western and glorified perspective. As evidenced in “The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History”, that many “museums now reinvent themselves by implementing policies of recognition for previously marginalised groups and attempt to repair historical wrong”.

Reflecting on the Complexity in Curatorial decisions on Colonial History

It is vital to reflect on the complex nuances in portraying colonial history. For example, placing the gold bust within the General Archives of the Indies is a strategic curatorial decision. This institution is dedicated to preserving and documenting Spain’s colonial history in the Americas, making it an appropriate context for displaying the representation of Hernán Cortés. However, considering how curators are attempting to shift the narratives of colonial museums to be more inclusive of marginalised groups, this bust quite clearly is an object meant to monumentalise a figure in history. The fact that the entirety of the collection on display in the Archives is focused on the stories of the conquerors, therefore questions the curators’ attempts in repairing any means of historical atrocities and wrongs. Furthermore, the fact that Spain is a diverse and multicultural country, which homes many native American citizens, displaying this bust questions the inclusivity of the narrative on colonialism that it is portraying. Despite it not being the original object, nor made out of exploited gold of the colonial era, the fact that a replica has been made, and chosen to be displayed on a plinth at the entrance of the collections on display, suggests a deeper societal and historical lack of awareness of the wrongs during the Spanish empire. Allowing the object to have such significance and power within the exhibit, allows the colonial narrative to continue to manifest. Further to this, the date which the object was created to replicate the original, was just as Spain had started to lose its’ colonies, marking an end of an era; an era of a global power, which has come to an end. One could interpret this reimagined object as an object that reminisces the old empire, as Spain contended with a national depression during the time it was created.

The background information that accompanied the object was limited. It only described, what it was, what it was made from, the fact it was a replica, and when it was made. There was no acknowledgement of the controversy or the complexity of displaying an object which monumentalises a figure, which South American people may find problematic. Curators of this exhibition, could have used the power of words to re-contextualise the bust to portray it in a perspective, where visitors can be invited to question its morality now, versus what it meant to society when it was created, to then compare the significance of it throughout time, and how that has changed. As mentioned previously, the lack of explanation and words, to me seemed very reminiscent of the Pacto del Silencio, a pact of silence, where perhaps the silence had also been applied to colonial history as well as the history of the Spanish Civil War. Without the presence of written context, it allows the object to symbolise power, wealth, exploitation and conquest. It is representative of the broader narrative of Spain’s colonial ambitions of the time. The object had potential and opportunity to overcome this by providing an element of educational value in its placement and description. For example, in this context, the bust can serve as an educational tool, helping visitors better understand the role of Hernán Cortés in colonial history. The General Archives of the Indies could have provided interpretive materials and contextual information to enhance visitors' understanding of the bust's significance within the broader colonial narrative. Furthermore, the bust may not have needed to be displayed on a plinth, which monumentalises it. It could have been chosen to be placed on a lower platform to draw less importance to it, which in turn would emphasise the controversy of its historical importance, which would engage the audience to question their perceptions and current knowledge of Spanish colonial history. I mention this due to the increasing cultural and historical awareness in dealing with colonial history. Curators often have to engage with ethical questions related to the representation of historical figures involved in colonisation and exploitation. The display of Cortés's bust may spark discussions about these ethical considerations and the legacy of colonialism.

In conclusion, the display of the 18th-century replica gold bust of Hernán Cortés within the General Archives of the Indies in Seville holds significant musicological value. It serves as a tangible link to Spain's colonial history, symbolises the colonial memory of that era, and offers educational and ethical dimensions for consideration. To further the relevance of this case study, it validated my research questions relating to how history is represented in Andalucía, and how the politics and regional history interplays with the production of history. As mentioned earlier in this paper, Andalucía is a region where Francoist nationalism still prevails. As known to my research, pride and glorification of the empire is directly related to Franco’s Spain. I found it thought provoking that the General Archives of the Indies, had no ‘indies’ collections, where diverse perspectives were explored, but the perspectives of those who had been glorified and remembered as historical legends up until 1975, when Franco died. This exhibition validated my initial enquiries on how this region would deal with the complexities of its colonial past.

Connect With Writer Now

Discuss your requirements with our writers for research assignments, essays, and dissertations.

Chapter 5 – Alternative Colonial Perspectives

Limitations

Creating unbiased historical colonial spaces in museums presents several formidable challenges. Firstly, one must question the production of history, therefore the implications that the production historiography poses on cultural institutions, where visitors with diverse perceptions, narratives and identities may portray history themselves. As Olena Mishalova says “these complicated situations clearly show us the close connection between history (its various versions) and the formation of our national, cultural and political identity. Thus, cultural and religious differences of various groups of the population and conflictual issues of the past – all this requires constant rethinking from the philosophy of history.

Drawing upon Michel Foucault's theory of history as an instrument of power and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's exploration of the subaltern's voice, we encounter the inherent flaws within historical production and the intricate complexities of crafting unbiased historical perspectives.

Foucault's perspective illuminates how history is not a mere objective recollection of past events but a construct that serves the interests of those in power. History, as a tool of the dominant discourse, is wielded to legitimise authority, reinforce societal norms, and often marginalise dissenting voices. It operates within a framework of ‘power-knowledge’, where those who control the narratives also control the truth. This dynamic perpetuates a skewed historical record that silences the experiences of marginalised groups, particularly indigenous peoples in colonial contexts.

Spivak's question, "Can the subaltern speak?" further unravels the complexities of historical representation. She highlights the structural limitations within society that prevent marginalised groups from having agency over an unbiased and truthful representation of their history. The subaltern, often voiceless and powerless, find themselves at the mercy of dominant narratives that perpetuate their erasure. Well-intentioned academics who attempt to speak for the subaltern can inadvertently do harm, reinforcing the existing power structures.

The combination of Foucault and Spivak's insights underscores that historical production is a fraught terrain where power dynamics and structural inequalities wield significant influence. Crafting unbiased historical perspectives requires dismantling these entrenched structures, challenging dominant narratives, and making space for the subaltern to reclaim their voice. It necessitates acknowledging the influence of power in shaping historical accounts and striving for a more inclusive and equitable representation of history.

In essence, the flaws within historical production lie in the inherent biases ingrained in the processes of knowledge creation. Addressing these flaws involves recognising the power dynamics that underpin historical narratives and actively working towards dismantling them. It entails listening to the voices that have been historically marginalised, allowing the subaltern to speak, and constructing historical perspectives that are more reflective of the diverse and multifaceted realities of the past.

In the Latin American context, Spivak’s theories of whether the subaltern really have a voice in society, is particularly relevant. Upon reflecting on the politics of Peru, those in hegemonic political positions of influence, rarely include native and indigenous perspectives and representation. During the 1980’s the Prime Minister of Peru, ordered a forced sterilization of women in indigenous communities in the Andes, where many women died during the dangerous procedure. Kwame Nkrumah writes; “Once a territory has become nominally independent it is no longer possible, as it was in the last century, to reverse the process. Existing colonies may linger on, but no new colonies will be created. In place of colonialism as the main instrument of imperialism we have today neo-colonialism”.

The post-colonial legacy, can therefore be re-interpreted as ‘neo-colonialism’, rather than post, which suggests the colonial society has ended, when one must reflect upon to what extent the colonial sentiments continued to manifest in Latin American communities. Peru only acts as one example of neo-colonial hegemonies in South America, however the reality is that racial subjugation is still prevalent in all corners of the old Spanish empire. These neo-colonial societies further validate Foucault’s theory of power and knowledge. Without indigenous representation and agency in higher positions of influence society, can cultural institutions and museums fairly tackle the idea of an ‘unbiased history’?

Museums often reflect the historical perspective prevalent when they were established, which in colonial contexts might glorify or justify colonialism, making it difficult to overcome this legacy of bias. The very artefacts displayed in these museums are often fraught with ethical issues, obtained through colonial exploitation, which is evident in my first case study in the Museu Etnológic de Cultures de Barcelona; where many stolen artefacts of spiritual and cultural significance are displayed for the public eye. Mary M Brooks highlights that “awareness of different traditions and concerns informing modern conservation theory and the problematic process of realising theoretical ideals in practice is part of the current discourse of conservation” within museums. Subsequently, questions of ownership and ethical display further complicate the matter. As … emphasises “who if anyone owns the past? Who has the right and responsibility to preserve cultural remains from the past? The role of curators is pivotal, as they wield significant influence over how narratives are presented, and their personal or institutional biases can significantly shape historical interpretations. In the case studies, it is clear that the underlying politics of each region overarches the wider perspective of representation, inclusivity and agency of the Latin American populations over their own stories. Moreover, the underrepresentation or absence of indigenous voices in the curation process perpetuates Eurocentric perspectives. Funding sources and political pressures can also lead to narratives that align with the interests of those holding the purse strings. Historical documentation itself is problematic, often reflecting the colonisers' viewpoint, side-lining or erasing indigenous histories, which was evident in the Archives Museum in Seville, where the history was represented through the coloniser’s perspective. As historical interpretations evolve, museums must remain open to re-evaluating their displays and narratives. Additionally, visitor expectations and limited resources pose further challenges, with museums sometimes feeling compelled to cater to existing biases and facing constraints in updating exhibits, as mentioned previously museums and other cultural institutions may have business and touristic pressures to adhere to.

Importance

(reference from books) The imperative of integrating indigenous perspectives into historical discourse cannot be overstated, as it represents a crucial step toward constructing a more comprehensive, ethical, and inclusive understanding of history. As illuminated by Robert Houle's poignant observation, colonialism persists as a contemporary reality for indigenous nations, highlighting the ongoing struggle for sovereignty and the inadequacy of labelling it as merely "postcolonial." This characterisation underscores the moral obligation to rectify

historical injustices and give due recognition to the enduring resilience and agency of indigenous communities.

Furthermore, the exploitation of indigenous histories, traditions, and monuments by the tourism industry, as elucidated in the statement "Their histories, traditions, and monuments are exploited by the tourist industry, however without payment of their due royalties," underscores the urgent need to incorporate indigenous voices. This incorporation ensures that indigenous narratives are not commodified for commercial gain but are instead respectfully and authentically integrated into historical narratives.

The acknowledgment of Latin America's unique historical context, as outlined in the statement "In Latin America, we are always bringing pieces together, collecting fragments, and melding races, many histories and diversified cultural experiences," is pivotal. It recognizes the intricacies of miscegenation, cultural diversity, and the lasting impact of colonization. To disregard these complexities is to perpetuate an incomplete and biased historical discourse that fails to encapsulate the richness and diversity of Latin American history.

Lastly, the establishment of institutions that both honour indigenous narratives and remain open to diverse influences is essential. Such institutions should not become isolated "ghettos" but rather dynamic spaces that empower indigenous communities to share their experiences and cultural heritage. In summary, the inclusion of indigenous perspectives is an ethical imperative that enriches historical discourse by acknowledging the ongoing struggles, cultural contributions, and complex histories of indigenous peoples.

In… states that native writer once said that “when someone else is telling your stories….in effect what they’re doing is defining to the world who you are, what you are, and what they think you are and what they think you should be” . Concurring with this notion is the idea that many tribal and native artefacts are “not meant for general distribution….The non-Indian (or in general western societies) does not have a right to examine, interpret nor present the beliefs, functions and duties’ of certain objects and artefacts on display” This argument can be applied to critique the Barcelona museum, where in fact many colonial objects from South America, and through the Transatlantic slave trade were looted and on display at the museum.

Despite these limitations, numerous museums are actively striving to address bias and promote inclusivity by collaborating with indigenous communities, reassessing artefact representation, and acknowledging the complex and painful legacies of colonialism.

During a recent visit to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City in 2023, I was able to reflect on some methodologies used in order to promote inclusivity. The concept of collaboration with indigenous communities was evident. Many of the artefacts on display had indeed been on loan to the museum from indigenous communities, who had given consent to displaying them. Furthermore, the exhibition acted as more of a ‘contact zone’ where the space was used to create this dialogue between natives and non-natives about the colonial legacy and how it transpires into the contemporary world. What I particularly found interesting was that on many of the information panels, were translations in specific tribal languages. Having researched the importance of linguistic variation, not only allows a greater means of promoting diverse nationalities and identities, but it also “allows for the consideration of diverse historiographic traditions and languages, preventing the provincialization or Anglicization of the global narrative.”. The exhibition became less of the traditional ‘cabinet of curiosities’ , where native communities were eroticised or othered, or where institutions converted these spaces “into ghettos where these groups exist and present themselves , but more of an activist exhibition, which aimed to educate the viewers’ and take them on a critical journey. This was evident at the end of the history exhibition, where it became an art exhibition of a contemporary Native American artist called Shelley Niro, where she challenged colonial dialogues which were executed through an array of thought provoking installations. By the end of the exhibition, I felt hopeful and empowered to be taking more active steps to decolonise the hegemonic system. This is the narrative Spanish institutions should be looking towards as inspiration to begin educating a highly hegemonic society, by addressing certain colonial, and subsequent neo-colonial themes.

Strategies for creating more inclusive colonial contact zones in cultural institutions

Drawing upon a recent visit to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City in 2023,

Creating more inclusive colonial contact zones within cultural institutions is essential for fostering a balanced and nuanced understanding of history while honouring marginalized voices, particularly those of indigenous communities. To accomplish this, institutions must adopt a multifaceted approach that actively engages and represents these communities. First and foremost, collaborative curation is paramount. This means involving indigenous communities and scholars in the decision-making processes of what artifacts to display, how to interpret them, and how to present their own histories. Authenticity is key; indigenous artifacts and narratives must be represented accurately and respectfully, avoiding the trap of romanticisation or exoticisation and instead portraying these cultures as dynamic and ever-evolving.

A critical element of inclusive colonial contact zones is the presentation of multiple narratives. Acknowledging the perspectives of both colonizers and the colonized allows visitors to critically engage with different viewpoints and fosters a more comprehensive historical understanding. Furthermore, critical interpretation should accompany exhibits, contextualising them within the broader power dynamics of colonial encounters.

Community engagement should be ongoing, with indigenous communities invited to host events, workshops, or performances within the cultural institution, fostering a sense of ownership and connection. Educational programs that challenge stereotypes and prejudices are also essential, including workshops, lectures, and school curricula that highlight the diverse and significant contributions of indigenous communities. Digital initiatives can provide a platform for indigenous voices, offering online exhibits, podcasts, or interactive experiences where these communities can share their stories authentically.

Transparency regarding the provenance of artifacts is vital. If objects were acquired through colonial violence or theft, institutions should openly acknowledge this history and explore potential avenues for restitution or repatriation. Diversifying the workforce within cultural institutions is equally crucial; hiring indigenous curators, educators, and administrators ensures that indigenous perspectives are integrated at all levels of decision-making.

Efforts to decolonise museum spaces should be a constant consideration. This might involve re-evaluating the physical layout, language, and aesthetics of exhibits to challenge colonial biases. It's also important to amplify indigenous voices by dedicating spaces for their stories to be heard through oral history recordings, artwork, or written narratives.

Establishing mechanisms for ongoing dialogue and evaluation with indigenous communities and visitors can help to continually refine the inclusivity of exhibits and programs. Collaborative exhibitions with indigenous artists and cultural practitioners can showcase contemporary indigenous art and culture, breaking free from static, colonial narratives. Highlighting the interconnectedness of colonial histories across different regions can further enrich the narrative, showing how colonialism had global implications and creating bridges between various colonial contact zones. Some institutions have gone as far as issuing formal acknowledgments or apologies for past wrongs as a significant step towards reconciliation and healing.

In summary, these strategies work together to transform colonial contact zones within cultural institutions into dynamic spaces that reflect a more inclusive, accurate portrayal of history. Such efforts not only promote social justice but also enrich our collective understanding of the complex interactions and legacies of colonialism, making them vital for fostering a more equitable and empathetic world.

Guaranteed Plagiarism-Free Work

Get 100% human generated plagiarism-free research content from our expert writers!

Chapter 6 - Conclusion:

In conclusion, this research project has undertaken an exploration of Spain's approach to managing its colonial history, uncovering an array of complexities which are woven into the fabric of its autonomous communities, and identities. Initially conceived as a study at the national level, the project took an unexpected turn, unveiling the profound influence of regional historical and political factors. Within Spain's diverse landscape, composed of seventeen autonomous communities, a shared desire to rekindle and safeguard historical memory emerges as a common thread. Yet, this unity is juxtaposed with a stark contrast in the interpretation and representation of colonial history in two distinct regions: Andalucía and Catalonia.

While both regions wrestle with the conspicuous absence of Native Latin American and Afro-Latin American perspectives within their cultural institutions, they do so through the lens of their unique historical and political contexts, which is driven by the Francoist legacy that predominates in Spain. Through the interplay of pact of silence, and the failure to confront traumatic histories in the 20th century, has overshadowed the narrative in cultural and historical institutions in contemporary Spain, whilst simultaneously neglecting colonial past and traumas which effect ancestors of the Spanish empire, whom form a part in Spanish society today.

These differences in both Andalucía and Catalonia underscore the pivotal role regional dynamics play in shaping narratives and maintaining a stranglehold on the colonial discourse. They also emphasise the need for a multifaceted approach to address the nuanced colonial legacy.

As mentioned, this research recognises the pressing need for alternative representation within Spain's cultural institutions. Drawing on inspiration from comparative case studies, including an exhibition in New York City at the Nation Museum of the American Indian, the project aspires to provide innovative methods for reimagining and revitalising the portrayal of colonial history, and Native American voice in contemporary society. These comparisons offer a glimpse into the transformative potential of enriching the colonial narrative, harnessing valuable lessons from the remarkable progress made in the United States.

It is also vital to exemplify the limitations within my own research; firstly, I mention the complexities of the hegemonic and structural functions of western society, and the subsequent ‘anglicization’ of this field of research. I wholeheartedly understand the contradictory notions that are of my western privileges in researching and providing my western narrative and perspectives on this research and on histories that are not mine to represent. However, with the utmost sensitivity, I have highlighted the absence of ethical considerations and appropriate inclusivity of cultural and historical production within Spanish institutions, which outline the limitations within its own societal and educational framework. I would therefore urge cultural institutions and non-profits to provide funding for ethnic minorities and marginalised groups to further this field of research, which will contribute to an increase of their agency on their histories, and provide alternative dialogues and conversations to densify the areas of research with academics who can provide a less western and Eurocentric stance. This would ultimately enrich current research. I would also urge current academics to continue their efforts in finding methods to collaboratively decolonise institutions and public spaces, in order to improve inclusivity.

In essence, this research project ventures deep into the intricate and region-specific dimensions of Spain's management of colonial history. It underscores the glaring oversight in recognising Native Latin American voices and the critical importance of safeguarding historical memory. By juxtaposing regional subtleties and drawing from international experiences, the project offers fresh insights and innovative strategies for reshaping the representation of colonial history in Spanish cultural institutions. Ultimately, this research contributes to the broader ‘Anglo-Saxon’ academia in promoting conversations on decolonising historical narratives and re-evaluating the complex interplay of regional and national perspectives in the retelling of a nation's history, when the nation (Spain) is already managing its own complexities of deconstructing a post-fascist society through its cultural and historical spaces.

Guaranteed AI-Free Work

Protect your degree from AI-Objectifying! Get 100% human generated research content!

Download PDF File

Download PDF File

Bibliography

Books, including e-books:

- Barton, Simon. A History of Spain. Red Globe Press, 2nd edition, 2009

- Borah, Woodrow Wilson. New Spain's Century of Depression. Vol. 35. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951

- Carr, David. The Promise of Cultural Institutions. London: Altamira Press, 2003

- Chambers, Iain, et al. The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History.Routledge, 2016

- Cooper, Karen Coody. Spirited Encounters: American Indians Protest Museum Policies and Practices.Rowman Altamira, 2007

- De Lima Grecco, G., and Schuster, S. "Decolonizing Global History? A Latin American Perspective." Journal of World History 31.2 2020

- Encarnación, Omar G. Democracy without Justice in Spain: The Politics of Forgetting. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014

- Gabara, Esther & Adey, Isabel. "The Bermuda Triangle of Madrid’s Museums: The Prado, the Museum of the Americas and the National Museum of Anthropology." Art in Translation 12.2 2020

- García-Álvarez, Jacobo, and Trillo-Santamaria, Juan-Manuel. Between Regional Spaces and Spaces of Regionalism: Cross-border Region Building in the Spanish ‘State of the Autonomies. Regional Studies 47.1 2013

- Gabilondo, Joseba. "Historical Memory, Neoliberal Spain, and the Latin American Postcolonial Ghost: On the Politics of Recognition, Apology, and Reparation in Contemporary Spanish Historiography." Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 7,2003

- Godreau, Isar P., et al. "The Lessons of Slavery: Discourses of Slavery, Mestizaje, and Blanqueamiento in an Elementary School in Puerto Rico." American Ethnologist 35.1 2008

- Hobsbawm, Eric. "Karl Marx’s Contribution to Historiography." In Ideology in Social Science: Readings in Critical Social Theory, edited by R. Blackburn 1972

- Impey, Oliver, MacGregor, Arthur.The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe.Oxford:Oxford University 1985

- Martínez, María Elena. "Social Order in the Spanish New World." PBS.When Worlds Collide 2010

- Messenger, Phyllis Mauch, ed. The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property: Whose Culture? Whose Property? UNM Press, 1999

- Mishalova, O. Naratyvna tolerantnist: vykhid iz labiryntu natsionalnykh istorychnykh naratyviv (Narrative Tolerance: Overcoming the Maze of National Historical Narratives).Actual Problem of Mind, p20 2019

- Monsod, Jean. "The Spanish Colonial Past in the Writer’s Memory: (Post)colonial Nostalgias in Enrique Fernández Lumba’s Hispanofilia Filipina." Transmodernity: Journey of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 6.2 2016

- Nkrumah, Kwame. Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism.1965

- Ortega y Gasset, José. "España Invertebrada." Austral, 2011

- Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts of the Contact Zone." In Ways of Reading, 5th edition, edited by David Bartholomae and Anthony Petroksky, 1999

- Riach, Graham. "An Analysis of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's Can the Subaltern Speak?" Macat International Limited, 2017

- Paul Preston, “The Spanish Holocaust” (HarperPress, 1st edition, 2013

- Rouse, J. "Power/Knowledge." In The Cambridge Companion to Foucault, edited by G. Gutting, Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, 2005

- Schwab, Gabriele. "Writing against Memory and Forgetting." Literature and Medicine 25.1 2006

- Sleeper-Smith, Susan (ed.).Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives, University of Nebraska Press, ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/leeds/detail.action?docID=452187. 2009

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books, London 2012

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. "Can the Subaltern Speak?" In Imperialism, Routledge, 2023

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples.Zed Books, London 2012

- Zytaruk, Maria. "Cabinets of Curiosities and the Organization of Knowledge." University of Toronto Quarterly 80.1 2011

Articles:

- Houle, Robert. "Vision, Space, Desire: Global Perspectives on Cultural Hybridity." Smithsonian NMAI, 2006

- Mesquita, Ivo. "Vision, Space, Desire: Global Perspectives on Cultural Hybridity." Smithsonian NMAI, 2006

- Pack, Sasha. Tourism and Dictatorship: Europe's Peaceful Invasion of Franco's Spain.Springer, 2006

Web Sources:

- G.M. Spiegel, Above, about and beyond the writing of history: a retrospective view of Hayden White’s Metahistory on the 40th anniversary of its publication. Rethinking History 17(4),492–508 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- G.M. Spiegel, The future of the past: History, memory and the ethical imperatives of writing history. Journal of the Philosophy of History 8, 149–179 (2014) [Google Scholar]