Technical details of runway layer works, compared to roads

January 28, 2021

Material Performativity for Biological Growth

January 28, 2021Learn about the UK's relationships with other countries for trade. Explore how the UK works with its trading partners.

The following text comprises the executive summary of the study.

Executive Summary

The international trading environment has been continuously changing since countries throughout the world have been recovering from the economic recession that hit 2008, as a result of the collapse of the Subprime bubble in 2006-2007. The United Kingdom is one of the world’s leading economies due to its rapid growth in 2014.

Various factors have impacted how the UK trades with its counterpart countries. Extensive research has shown findings of the UK’s trade trends being influenced by the New Trade Theory (NTT). This is thought to be the reason which its top ten trading partners include:

- USA

- China

- Switzerland

- Republic of Ireland

- Canada

- Belgium

- France

- The Netherlands

- Spain

- Germany

The top ten trading partners for the UK were selected based on most exports, imports, and foreign direct investment. The data was obtained from HM Revenues and Customs sheets analysing trends from 2011 to 2014. From the research, it is found that all trading partners are influenced mainly by tariffs, distance, and political & legal environments.

A great British hobby was predicting what the weather might be next, which was essential for many 19th-century traders. This was because trade winds would affect the number of ships that may be arriving at Britain’s ports, further influencing the money markets.

Introduction

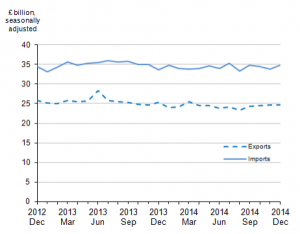

Trade had become such an important aspect of life at the time that even the Bank of England placed a weathervane on their roof to help in making market decisions. Like in the past, trade is just as important today. In 2013, the UK made up 3.0% of the world’s merchandise exports, about USD 549,030,000 exports 2013 (WTO, 2014: 24). According to the World Trade Organization (2013), in 2013 the UK ranked number 8 as a leading exporter in world merchandise trade, with a merchandise trade value of 542 billion USD, having an annual percentage change of 15%. The figure below illustrates the UK’s seasonally adjusted value of trade in goods, as per the Office National Statistics, 2014

Figure 1; Value of UK goods in trade (Source: ONS, 2014)

The method by which the UK interacts with its trading partners influences international trade. This study will examine factors and various trade theories that explain the trade patterns of the UK with its 10 main trading partners.

United Kingdom Trading Patterns

Based on IMF (2015) findings, the UK has the fifth largest national economy based on nominal GDP, and the ninth largest in the world, based on purchasing power parity. Today, the UK is considered one of the world’s most globalised economies, a dominating role it has played being the first to industrialize in the 18th century and playing a dominant role in the global economy in the 19th century. Like many world economies recovering from the 2008 recession, the UK experienced negative growth for two consecutive quarters in 2012. But by the close of 2014, it has become one of the fastest-growing G7 economies with employment rising to the highest figure since its recession period comeback (WTO, 2014).

The Office for National Statistics (2015) has asserted that UK trade is the key contributor to the overall economic growth in the country. In 2013, the UK was considered the leading country in Europe for inward foreign direct investment (FDI) of 26.51 billion USD, giving the country a 19.31% market share in Europe alone (FDI Intl., 2014). While for outward FDI, the UK has gained a 17.24% market share of Europe with 42.59 billion USD (FDI Intl., 2014).

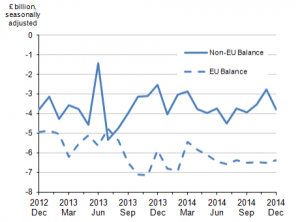

The UK’s trade with neighbouring European countries is necessary, with seven of the ten main export destinations of the UK being in the EU. However, non-EU countries are increasingly becoming more significant, as evidenced by the data obtained from ONS, 2014;

Figure 2; EU & non-EU country's balance of trade 2014 (Source: ONS, 2014)

Based on a country level, the UK’s leading destination for exports is the American market, with a large trade surplus coming from Ireland (The Economist, 2013). France is considered to be both a large exporter and an importer of the UK. Germany, the Netherlands, and China are countries that have developed the UK’s largest deficits. Based on the UK’s 2014 exports, Switzerland has also become a leading trade partner, along with Canada, Spain, and Belgium. The figure below illustrates the top ten trading partners based on exports and imports with the UK in 2014 (HM Revenue and Customs, 2014).

Figure 3; Trading patterns of the UK in 2014 (Source: HM Revenue and Customs, 2014)

Various factors influence trade between countries, with some factors encouraging trade and others deterring trade.

Factors Affecting UK Trade Patterns

UK has the advantage of being a member of WTO since 1995, GATT since 1948 and various RTA’s. Firstly, two factors which are interrelated with one other are political and legal factors that impact trade between the UK and its partners. Despite the globalization of businesses, firms must accept and act based on local rules and regulations of the countries to which they operate or export. Thus, global businesses need to observe and assess the political and legal climate in countries where they trade in, goods or services.

Based on the UK trade partners, all countries except for China are pluralistic regimes that practice democracy. China is more of an authoritarian government with its strong government and limited individual rights. However, over the past two decades, China has pursued a new balance between how much the state plans and manages the national economy. Today, China has been successful in merging state intervention with private investment to bring forth a robust, market-driven economy, while still using the communist form of government (Carpenter and Dunung, 2012).

Other factors that affect international trade between trade partners of the UK include relevant policy variables: tariff, inflation, exchange and capital control, gross domestic product (GDP), import duty, and foreign direct investment. According to Raballand (2003), foreign direct investment increases the host country’s exports, although the impact on imports is considered relatively weak. When tariff barriers are present, restrictions on FDI begin to increasingly distort trade. A tariff barrier in the importing country has a negative effect which is insignificant on the effect of exports to the country. Furthermore, per capita, GDP and population are factors that play a significant positive impact on exports. However, distance between countries hurts trade, as trade costs that include transportation and communication increase in regards to distance (Raballand, 2003).

Standard gravity variables of distance as an indicator of transport costs play an influential role with the UK and its trading partners. Countries that are the UK’s trade partners are those that are a shorter distance, comprising mostly EU countries, while non-EU countries US and Canada are also a short sea and air distance from the UK, with an average distance being 6,800km, and air distance equalling 4,200km. Commonly, neighbour countries have more integrated logistics networks which reduces trans-shipments. Furthermore, neighbouring countries are also more likely to have transit and customs agreements that decrease the transit time and lower shipping & insurance costs. Thus, distance affects trade volumes through transportation costs. Furthermore, there are low tariff rates between organizations of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

Trade Theories

International trade can be defined as the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. Based on the time in history, trade methods and theories have been expanding and adjusting themselves. The 15th and 16th century trade was defined by mercantilism which stressed that countries should simultaneously encourage exports and discourage imports; a common concept that still resonates in modern trade policies. It was Adam Smith who can be traced back to today’s standard theory of international trade with his Wealth of Nations, followed by David Ricardo’s Principles of Economics, published in 1951. Adam Smith’s absolute advantage argued that the wealth of a nation depends on goods and services available to its citizens rather than on the gold reserves of sovereigns. Maximizing the availability depends on putting all resources to use and then on the ability to obtain goods/services; to pay for them by production of goods/services produced more cheaply in the country, and costs measured in terms of direct and embedded labour inputs.

This principle fits the development of capitalist economies based on production through wage labour. Schumacher (2012) asserts that Smith’s theory was established as a predecessor to the theory of comparative advantage. Ricardo’s comparative advantage asserts the possibility of system-wide gains from trade occur even if the country has no absolute advantage in the production of no product. Helpman (2010) emphasized interactions of policies and regulatory frameworks with the specific needs of specific sectors of the economy having a comparative advantage over others. Furthermore, the Ricardian comparative advantage was implemented in the importance of financial institutions for development by Beck (2003) and Manova (2008) revealing that countries with better financial development export more in sectors that have a greater tendency to depend more on external financing, based on a study of OECD countries. Levchenko (2007) has also agreed with Ricardian comparative advantage with the study asserting that countries with better rule of law have been shown to export comparatively more in sectors that have lower levels of input concentration.

Although not a particular theory, the Heckscher-Ohlin model is used to evaluate international trade, specifically trade equilibriums between countries that have different features. The general principle of the model is; that by trading goods, countries are indirectly trading factors that are contained in the production of those specific goods. The model was tested for the USA by Baldwin (1971) based on the country’s commodity structure. The results of the factor content of US exports and imports in 1962 by Baldwin (1971) are summarised in the table below showing that K/L was higher in imports, however, the US was much more capital-abundant in 1962 than compared to the rest of the world.

Table 1; Import / Export primary factors (source: Baldwin, 1971)

Factor Content of U.S. Exports and Imports for 1962 | ||

| Imports | Exports |

Capital per million dollars | $ 2,132,000 | $ 1,876,000 |

Labour (person-years) per million dollars | 119 | 131 |

Capital-labour ratio (dollars per worker) | $17,916 | $14,321 |

Average years of education per worker | 9.9 | 10.1 |

The proportion of engineers and scientists in the workforce | 0.0189 | 0.0225 |

Lastly, the New Trade Theory (NTT) is a collective economic model in international trade that emphasizes the role of increasing returns to scale and network effects. The assumption of constant returns to scale is relaxed. An important source and destination for FDI has become high-income industrialised countries such as the UK. Just in 1997, the total outward FDI stock of the US, Japan, and the EU was equal to 1560 billion GBP with 63% of this amount concerned with FDI stock just within the EU, Japan, and the US (UN Intl Trade Stats, 1997; WIR, 1999).

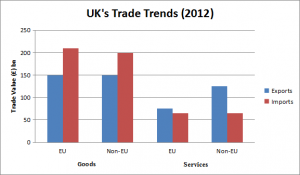

Since there has been an increase in both intra- and inter-industry trade between more developed and industrialised countries, the NTT has been increasing its effort to support the increased importance of trade between industrialised countries and the frequency of intra-industry specialisation between them. Using the NTT as a premise, Markusen and Venables (1998) develop a framework to analyse the increasing importance of FDI regarding trade in the world economy. Using a two-country model, Markusen and Venables (1998) assert that the convergence of countries in size and relative endowments moves the trend from national to multinational firms; known as the convergence hypothesis, in which multinational production displaces national firms and trade as the two countries converge either by relative size, relative factor endowments, or relative production costs. This is evident in the US-UK trade relationship with the UK comprising of 25% share of the American economy (The Economist, 2013). The leading importers of the UK’s Oxford-made BMW Mini are the USA, Germany, China, and France (The Economist, 2015). The same relationship can be seen with UK-EU countries. According to the chart below, by 2012 Britain’s exports and imports largely depended on goods and services from EU countries.

Figure 4; Trade trends of the UK in 2012 (Source: ONS, 2012)

It is an accepted idea that free trade benefits all countries in the world; although, hardly any country has practised free trade policies thoroughly. However, the UK believes in free trade as the economy is dependent on foreign trade making the government support unrestricted trade. Due to its dependency on trade, the UK has few restrictions on foreign trade and investment. Furthermore, the strength of the Great Britain Pound and its state economy has made the country an attractive investment place for foreign investors. The UK government has adopted numerous programs to promote and attract foreign businesses and investments. One of the key programs has been allowing local and regional governments to establish enterprise zones in which companies receive exemptions from property taxes and reimbursements for costs that are involved in the construction of new factories or business locations. The country also hosts free trade zones in the UK allowing goods to be stored for shipment without tariffs or import duties.

The UK and its top ten trade partners vary in relative size, trade policies, and population.

Conclusion

However, since 2014 the UK has been trading with these particular countries further strengthening its ties. The UK believes in free-trade and this idea is expressed with its trade policies and willingness to persuade other countries to promote such policies for themselves. This is evident from the countries current negotiation of international trade agreements such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and US (GOV UK, 2015). Furthermore, the UK is expanding using the EU’s free trade agreement with South Korea, allowing UK companies to do business there as well (GOV UK, 2015).

Based on UK’s top ten trading partner, it is evident that the trade policies associated with the country are more related to the New Trade Theory (NTT) as it is currently trading in terms of volume of import and export with fellow highly industrialised countries. This is due to factors of lower tariffs with EU countries, and relatively closer distance to trade in terms of communication and transport with these countries. All of UK’s trading partners are large democracies with pluralistic regimes, except for China. This aids in trading being carried out more smoothly due to commonality between laws and regulations. There is also strong political stability within these countries which decrease the change of risk that UK companies may face in countries with political instability.

References

Baldwin, R., 1971. ‘Determinants of the commodity structure of U.S. trade’. American Economic Review, 61, 126-145.

Carpenter, M. A., and Dunung, S. P., 2012. Challenges and Opportunities in International Business (Edition: 1.0). Creative Commons

Department for Business Innovation & Skills (BIS)., 2010. ‘UK trade performance’: Patterns in UK and global trade growth. BIS Economics Paper, No. 8. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32114/10-803-uk-trade-performance-growth-patterns.pdf. [Accessed: 18 August 2015].

FDI Intelligence (FDI Intl.)., 2014. The fDi report 2014. Available: http://www.fdiintelligence.com/Landing-Pages/fDi-report-2014/fDi-Report-2014-Europe#Main. [Accessed: 16 August 2015].

Government of United Kingdom (GOV UK), 2015. ‘2010-2015 government policy’: free trade. Department for Business, Innovation & Skills. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-free-trade. [Accessed: 16 August 2015].

Helpman, E., 2010. ‘Labor market frictions as a source of comparative advantage with implications for unemployment and inequality. NBER Working Paper, No. 15764.

International Monetary Fund (IMF)., 2015. Report for selected countries and subjects. International Monetary Fund. Available: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=83&pr.y=16&sy=2015&ey=2015&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=193%2C273%2C223%2C156%2C924%2C922%2C132%2C184%2C134%2C534%2C536%2C136%2C158%2C112%2C111%2C542&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=0&a=. [Accessed: 17 August 2015].

Levchenko, A.A., 2007. ‘Institutional quality and international trade.’ Review of Economic Studies,74, 791-819.

Manova, K., 2008. ‘Credit constraints, equity market liberalizations and international trade.’ Journal of International Economics, 76, 33-47.

Markusen, J. R., and Venables, A. J., 1998. ‘Multinational firms and the new trade theory.’ Journal of International Economics, 46, 183-203.

Morgan, R. E., and Katsikeas, C. S., 1997. ‘Theories of international trade, foreign direct investment and firm internationalization’: A critique. Management Decision, 35 (1) 68-78. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00251749710160214. [Accessed: 15 August 2015].

Office for National Statistics., 2015. ‘UK trade, June 2015.’ Office for National Statistics. Available: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/uktrade/uk-trade/june-2015/stb-uk-trade--june-2015.html. [Accessed: 16 August 2015].

Office for National Statistics. 2015. ‘UK Trade, December 2014’ [Accessed: 18 August 2015].

Office for National Statistics (ONS)., 2012. UK, trade, December 2012 Release. Office for National Statistics. Available: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-270799. [Accessed: 17 August 2015].

Raballand, G., 2003. ‘Determinants of the negative impact of being landlocked on trade’: An empirical investigation through the central Asian case. Comparative Economic Studies, 45, 520-536.

Schumacher, R., 2012. ‘Adam Smith’s theory of absolute advantage and the use of doxography in the history of economics.’ Eramus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, 5 (2), 54-80.

Sen, S., 2005. ‘International trade theory and policy’: What is left of the free trade paradigm?. Development and Change, 36 (6) 1011-1029.

The Economist (2013): An Island of Traders (Edition: May 2013, print). The Economist. Available: http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21578085-britains-fastest-growing-trade-links-are-really-re-emergence-old-ties-island-traders. [Accessed: 16 August 2015].

World Trade Organization (WTO)., 2013. ‘Fundamental economic factors affecting international trade.’ World Trade Organization. Available: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr13-2c_e.pdf. [Accessed: 16 August 205].

World Trade Organization (WTO)., 2014. ‘International trade statistics 2014.’ World Trade Organization. Available: https://www.wto.org/English/res_e/statis_e/its2014_e/its2014_e.pdf. [Accessed: 15 August 2015].

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?