Exploring the Significance of Change Management in Construction Projects

December 19, 2020

Exploring BIM in Design Coordination Along With Integrated Project Delivery

December 20, 2020Economics is the study of how societies manage their limited resources to meet diverse needs and desires. It delves into understanding production, distribution, and consumption to navigate the complexities of global markets and individual decision-making. In a world where economic landscapes can change in the blink of an eye, individuals, businesses, and governments must develop strategies for financial resilience. Economic uncertainty, brought about by various factors like global crises, political events, and market volatility, can pose significant challenges.

However, by understanding the dynamics of economic uncertainty and implementing sound financial practices, you can better weather the storm and come out stronger on the other side. Adapting and preparing for the unexpected is key in this fast-paced economic environment. Businesses must be agile, individuals must be financially savvy, and governments must enact policies that promote stability and growth. This blog explores the nature of economic uncertainty and offers strategies for achieving financial resilience in a world where change is the only constant.

Question 1: What Role Does Persuasion Play in Helping Parties Capture the Median Voter?

Andrew Hindmoor (2005) posits that Anthony Downs's (1957) Economic Theory of Democracy offers more than its widely recognized assumptions and predictive analysis pertaining to the median voter theorem. While the median voter model has made significant inroads in political frameworks, its success in capturing the median voter and securing the majority can be better understood beyond the quantitative assumptions and calculated predictions at the core of the theorem. Hindmoor (2005), in his 2005 article titled "Reading Downs: New Labour and an Economic Theory of Democracy," contends that New Labour's actions and policies held a more profound significance than what can be discerned from the voter theorem alone.

The median voter model suggests that political parties can secure the median voter and maximize their votes by adjusting their ideological priorities and influencing the voters' perceptions. In 1997, New Labour won the election after four consecutive defeats under the Thatcher government, marking a significant shift from a left-wing philosophy to a more moderate, centrist approach. By realigning their political stance toward the centre of liberalism, the political party achieved dominance by effectively aligning their policies with the voters' beliefs. This demonstrates a broader perspective than the assumptions outlined by Downs for the median voter model, which typically reveals only one dimension of New Labour's political approach.

In his theory, Downs (1957) discusses the power of persuasion in gaining voter confidence, and these arguments, though not explicitly stated, can be extended to support New Labour's political trajectory. It is essential to first clarify Downs' assumptions for the median voter theorem and how they relate to New Labour's political ideology and strategy, indirectly underscoring the role of persuasion in securing the majority vote. Downs (1957) primarily argues that political parties and voters, operating in conditions of uncertainty and incomplete information, have the opportunity to use persuasion and influence to bring about paradigm shifts and alter voters' ideological preferences.

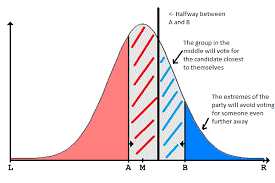

Today, the empirical and theoretical aspects highlighted by the median voter theorem are applied to political strategies and electoral contests, focusing on elements like candidate convergence and proximity voting. Downs' (1957) assumptions clearly emphasize the need for parties to adopt a more centrist approach to influence voters' mindsets and reshape their priorities. According to him, in an electoral contest with two parties, voter preferences can be mapped onto a one-dimensional left-right scale. Political parties, aiming to maximize votes, can position themselves at any point along this spectrum. Voters typically opt for the party closest to them on the political spectrum, with their preferences anchored in the information available about party policies and ideologies.

This aligns with the more straightforward and optimistic Rational Choice model that assesses and predicts political voting behaviour, akin to established economic models for evaluating or predicting consumer behaviour. These aspects shed light on voter psychology dynamics and the use of influence and persuasion by political parties to capture the median voter. Thus, a median voter is defined as a voter with an equal number of people to their "right" and "left." As described by Downs (1957: 114-141), the median voter model is a framework that primarily concerns the behaviour of political parties, rather than the feasibility of competition. It delves into areas of voter behaviour and party actions that can enhance voting efficiency. These core areas are elucidated through seven assumptions concerning party behaviour and voter preference dynamics.

The first assumption posits that "A political party is a 'team of men seeking to control the governing apparatus by gaining office in a duly constituted election" (Downs 1957: 25). In this view, there is no individual choice, as each party member shares common beliefs and goals. The second assumption reflects the voter's inclination to choose a particular party, suggesting that voter preferences are single-peaked and diverge monotonically from the party's ideology. Voter assessments of parties are grounded in the proximity of their beliefs to the policies of political parties, and as such, voter beliefs are considered exogenous to the actions of the party. Further assumptions assert that voter turnout reaches its maximum potential relative to eligible voters, parties are free to position themselves anywhere in the political landscape, and parties possess complete information about voter preferences and trends. Lastly, parties assume positions in parallel with other political parties without knowledge of their location, and they are motivated by the maximization of votes, which directly impacts their utility.

Figure 1: Median Voter Theorem (G-static, 2015)

Based on these seven assumptions, the predictive result of a two-party election will be convergence at the median of the voter preferences diaspora.

Although Anthony Downs's assumptions revealing elements like voter preferences, candidate policies, and candidate location significance above have been disputed following his work, they tend to highlight salient aspects of how political parties should behave and the actions to be undertaken for winning an electoral contest. According to Andrew Hindmoor (2005), the success of new labour in 1997 was attributed to their transition into a more centrist approach that bonded with the voter's beliefs and significantly influenced voting preferences. This transition did not require a major shift in policy as opposed to Downs theory since they maintained most of their policies. Their persuasive acts and the application of the new ideology, augmented through a successful electoral campaign, facilitated the shuffling of voters’ 1st and second-level preferences. Hindmoor's (2005) preferences formation reflects three levels of prioritized voter preferences that the political parties can use to capture the median voter through persuasion and policy formation. Following is the order of the preferences:

- 1st order: ideology, conception of the good society

- 2nd order: preferences over policies

- 3rd order: preferences between parties

Parties can persuade voters regarding their policies and how they transcribe to societal goals and community welfare, influencing their preferences between parties and preferences regarding policies. New Labor was able to persuade their voting pool about the merits of their policy. It achieved electoral success by applying aspects from the median voter's theorem, including adopting a more centrist approach and persuasive strategies.

Although the approach is effective, Downs's (1957) theorem nevertheless lacks predictive capacity. Then there are aspects like Asymmetric information regarding the median voter, voter turnout not exactly 100%, rational ignorance by voters, exogenous change of values or moving voter preferences and vested party members interested that are more self-centred. Further, Hindmoor's (2005) arguments overlook other aspects significant to electoral success, like the media's role and propagation's benefits relative to the election campaign. He also tends to overlook who the information supplier is and what are the vested interests.

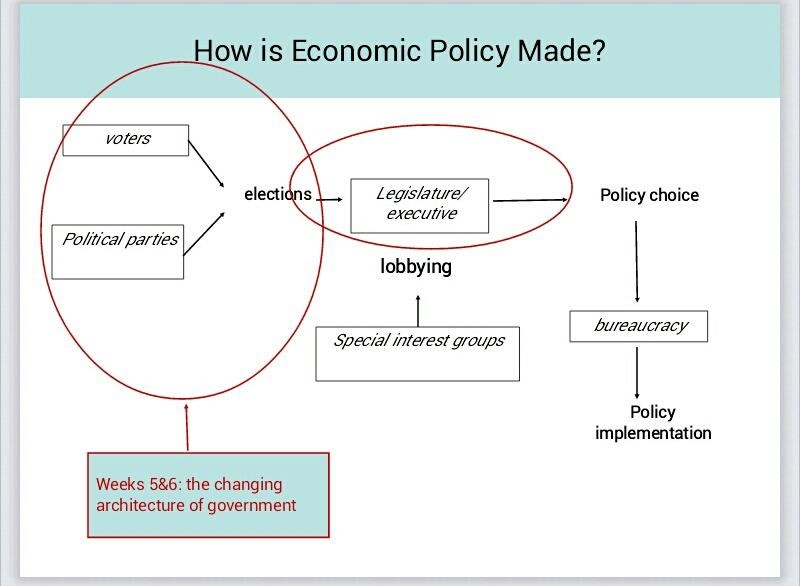

Question 2: To What Extent Do Formal Constitutional Rules Affect Government Spending, Taxation, and Corruption?

When it comes to studying the influences of economic and political outcomes relative to the various underlying political and institutional bodies in the community, the primary intention is to study and analyze the transformational impact of policies and related institutional legislation on economic development or prosperity. This study specifically aims to outline how the various forms of government and electoral rules directly impact economic dynamics. The empirical study by Persson and Tabellini (2003) emphasizes the effects of electoral rules and forms of government on fiscal policy (expenditure, taxation, deficits) and corruption.

Using a calculated empirical strategy, the study focuses on the impact of the types of government forms and their policy formation on economic entities such as taxation, spending on development, community welfare, including other arenas and the impact on corruption. The study uses a sample of 85 democracies and countries in the 1990s, shedding light on government spending and how the various electoral rules impacted the economic aspects, surveying the public choice theory to support arguments. It also uses a data panel set to analyze how nations change over time.

The study highlights the various voting systems, primarily the Majority Election System and the Proportional representation system. To understand the impact of constitutional rules, it's mandatory to get an insight into the forms of government and voting systems as they directly influence economic decisions.

Voting Systems

In the Parliamentary elections, there are two types of voting systems.

- The Majority Election System

- The Proportional Representation System.

Each system has its advantages and weaknesses, hence the economic impact. The core elements, however, to be considered are the equality in the individual impact of each vote on the electoral consequence and the political framework stability.

Majority Election System

In this particular system, only one member is elected as the member of the Parliament relative to each constituency where the voter count residing in the area and the location are considered election system units. Generally, the most apt and qualified candidate is selected to become the member of parliament to represent the constituency.

Proportional Representation System

With the proportional representation system, multiple members of the parliament are elected for each constituency. The process involves every political party presenting a candidate's list, and voters can choose a list, which technically means they indirectly vote for a political party. Political Parties are then allotted parliamentary seat representation proportionally to the number of votes they obtain. In this particular form, competing parties play a pivotal role in developing political concepts and defining situations (Bill et al., 2010).

Identification of Political Economies

In their particular study, Persson and Tabellini (2003) have highlighted the causal effects of the various factors of constitutional rules that also tend to impact economic dynamics. The basic idea is to understand the differences in policies for each form of government and how they tend to influence government spending. This is because various political institutions will have differing policies so the economic outcome would vary depending on the decision-making and relative legislation. Hence, political and economic agents or variables should have transformational or induced preference over political institutes and policies, clearly understanding the implications of both entities.

The study considers political parties as endogenous entities in political economies as supported by empirical theories and comparative politics. According to Charles Beards' (1913) study, the constitutions and government's prime concern is ensuring economic harmony for political power entities.

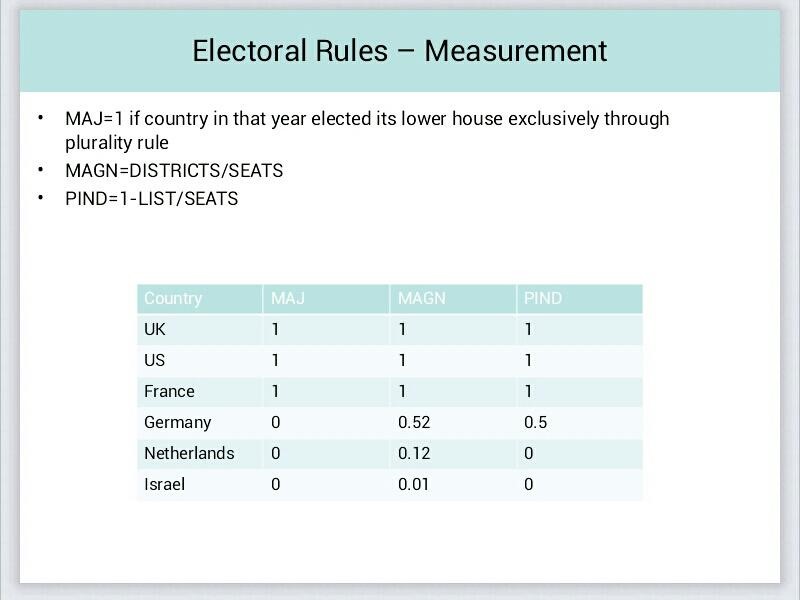

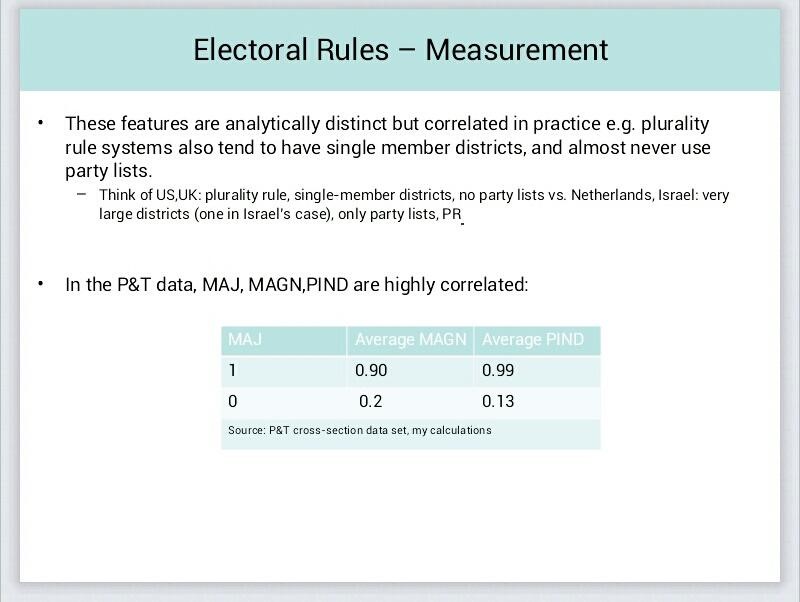

Figure 3: Electoral Rules Measurement. (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

As highlighted by the figure above, the study took into consideration aspects like:

- How many candidates were elected from each district? (District magnitude)

- How vote shares are converted into seat shares (electoral formula): plurality rule or proportional representation.

- With plurality, usually k=1: single-member district plurality or SMDP

- Also, plurality is possible with k>1 member districts; candidates are sequentially elected based on several votes.

- Pure PR: Party seat shares in an electoral district are proportional to votes.

- Districts tend to be large to make this work, but still “integer problems”: various formulae to deal with this (e.g. D’Hondt method)

How voters cast their ballot, e.g. single individuals or for party lists (ballot structure) (Ben Lockwood, 2015).

Figure 3: Electoral Rules Measurement. (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

Analysis of Presson and Tabellini's Study

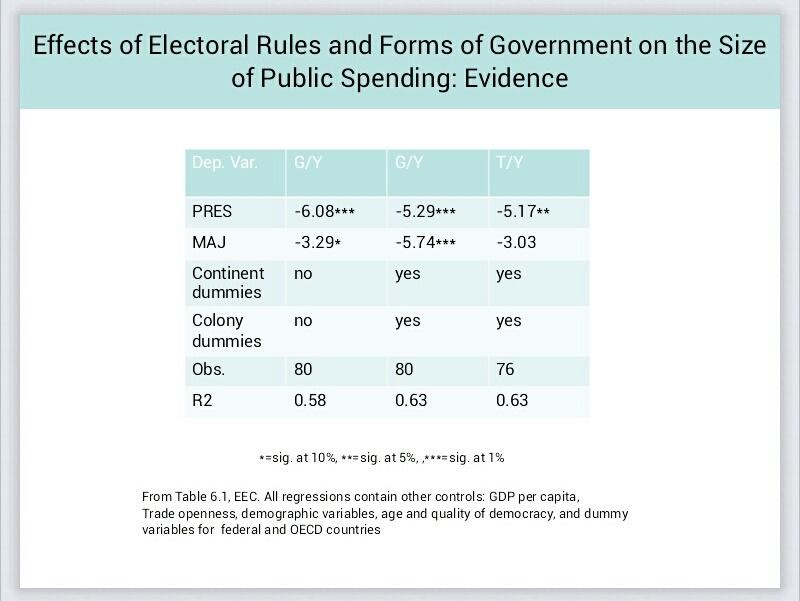

Based on all four strategies, Presson and Tabelleni (2003) deciphered several results that highlight a broader and more consistent image. The most important results are:

- Majoritarian and presidential systems have comparatively small governments compared to proportional and/or parliamentary representational systems. The Majoritarian systems, also termed MAJ, are considered to have lesser budget deficits and state welfare spending.

- Although the presidential (PRES) or majoritarian systems typically may not have an aggressive impact on political rents, corruption and collective productivity, certain aspects of the electoral system, essentially, the amounts of districts and whether or not the potential voters would cast their votes for individual politicians or would they vote for the parties, do have important

- Nations with parliamentary systems have more consistent fiscal results than those with a presidential system. Generally, in parliamentary systems, enhancements in governmental budgets during downward trends are not upturned during the upward trend. There is a related but weaker trend for countries with proportional representation (compared to those with majoritarian elections).

- Lastly, proportional representation also tends to increase welfare spending in the immediacy of elections, which matches the expected results of the political business cycle models. This is highlighted in the figure below.

Figure 5: Effects of Electoral Rules and Forms of Government on Public Spending (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

Figure 6: Effects of Electoral Rules and Forms of Government on Public Spending (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

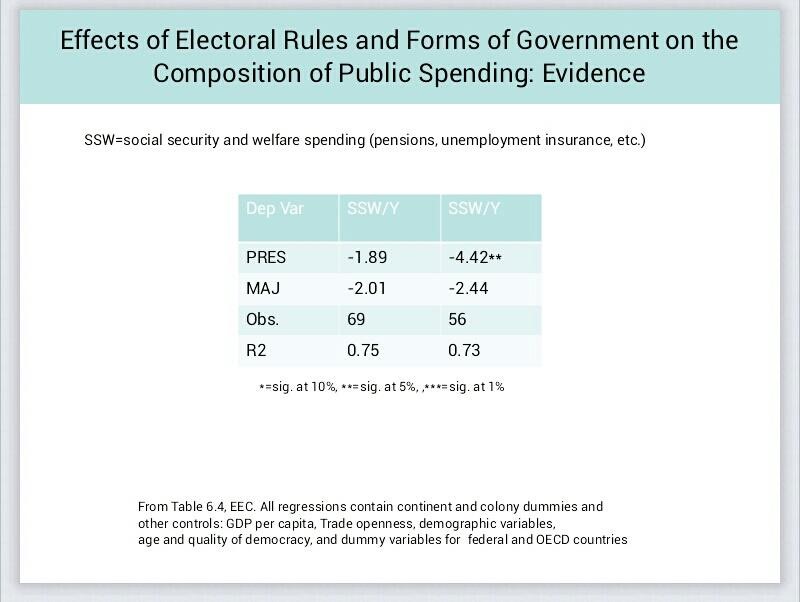

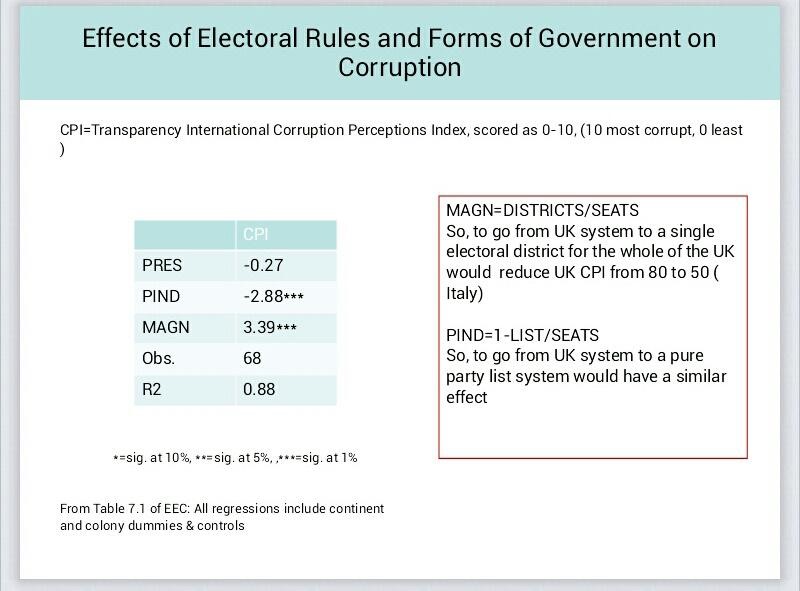

Trends show that small districts plus plurality imply spending targeted at small groups (local public goods), whereas large districts plus PR imply spending targeted at large groups. Empirically, the study evaluates broad spending by analyzing social security and welfare spending. Some theoretical models, like Milesi-Ferretti et al. (2002), predict smaller total spending with small districts plus plurality. As per the study, the following are the effects of Corruption:

- Corruption (specifically rent extraction) is likely to be higher with party lists, as individual legislature members are less directly accountable.

- It also highlights the Free-rider effect, reflecting that winning is based on the total number of votes for the party list, not the individual member.

If party leaders define lists, then factors like party loyalty and nepotism will favour the presence of a name rather than competence.

Figure 7: Effects of Electoral Rules and Forms of Government on Corruption (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

Predictions

Trends reflect that separation of powers (between president and legislature) is stronger in presidential forms of government because of the greater concentration of powers in parliamentary rules, as it is easier for politicians to collude at the voters’ expense. When formally modelled, the prediction is that this will lead to higher overall expenditure, increased taxes and more corruption in parliamentary systems. (Bill Lockwood, 2015). Confidence requirement in parliamentary systems promotes party discipline and legislative augmentation or cohesiveness. The effect is that spending is directed towards broader programs for most voters, such as social security programs. Comparatively, lack of legislative cohesion in presidential systems reflects trends like spending in the constituencies of dominant office-bearers, e.g. heads of congressional spending committees in the US (An example is pork barrel spending).

Proportional Representation vs Plurality Rule: Election Rules in a Downsian Model with Probabilistic Voting

As per PT's study, below is an explanation of the Proportional representation vs Plurality Rule for PR vs MAJ election rules.

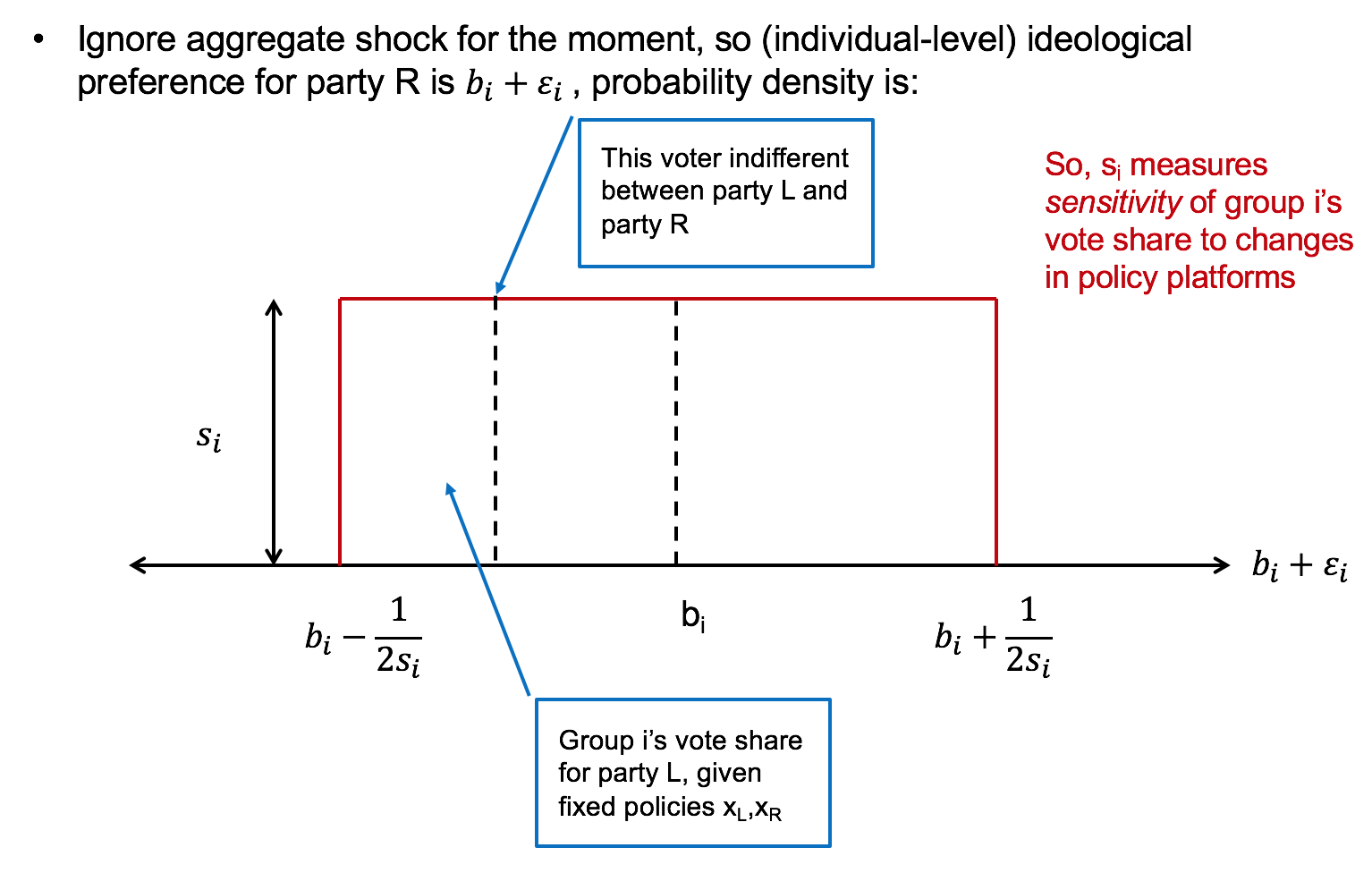

The following scenario is to be considered:

- There are 2 parties.

- Downsian assumes that the parties compete based on platforms. Parties must implement what they promised when in office.

- There are three groups of voters i= L/M/R, where each is 1/3 of the entire population.

- Group 1 gets party platform payoffs as highlighted below

- Group 1 has an ideological preference for party R that can be evaluated as

- Preference is group bias.

- A uniformly distributed individual-level preference.

- An aggregated shock that is uniformly distributed on [-1,1].

The Figure 8 below highlights the ideological preference and the distribution;

Figure 8: Ideological Preferences (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

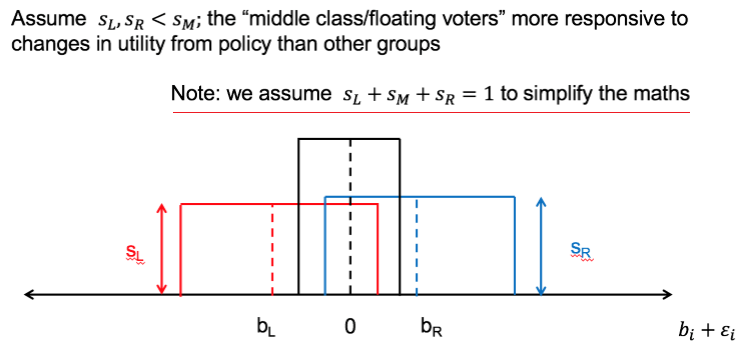

Now, considering the middle class or floating voters, it can be further characterized as;

Therefore, the probability calculations can be undertaken as below;

Figure 9: Distribution of Ideological Preferences within and across groups

(Ben Lockwood, 2015)

The following aspects are hence applicable in equilibrium:

Figure 10: Equilibrium Aspects (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

The figure below provides the algebraic dynamics relative to the Maximization of utilities by the party.

And;

Figure 11: Algebraic Explanation (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

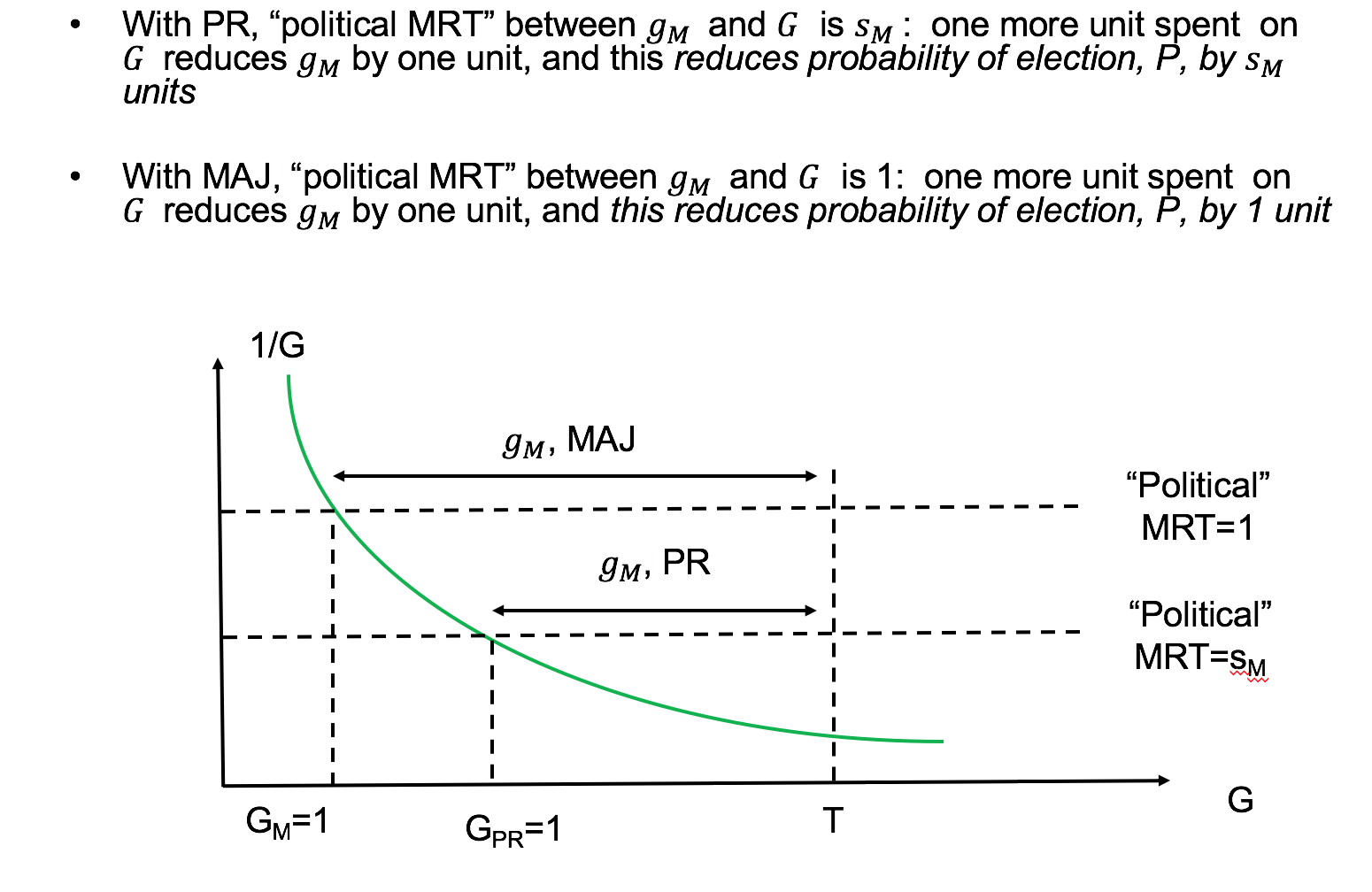

Similarly, the relationship between political MRT and MAJ can be outlined below;

Figure 12: Algebraic Explanation (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

Since now the parties are corrupt, they are concerned with winning the election and rent and D (diverted taxes). The objective is P (E+D), as they can only get rent when they win, where E is Rogoff's Ego Rent. This evaluates intrinsic satisfaction from the office. Furthermore, the consideration is how P's probability of winning the election decreases with D. The higher the response, the lower the rent will be in the political equilibrium. Moreover, it is also important to;

Figure 13: Algebraic Explanation (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

As per the figure above, there is more 'Bang for the buck' in the M system relative to the tax revenue; hence, it is more expensive to divert rent.

Conclusion / Executive Summary

The study reveals that PR and MAJ systems deliver too much targeted public goods and too little global public goods compared to the defined effective benchmark. Highlighting government failure, the electoral returns to targeting benefit the politically privileged median voters who exceed their shares in the population. This bias is worse for a majoritarian system of governing. However, the trends show that the MAJ system is likely to imply lower levels of corruption than the PR system. This is consistent with Presson & Tabellini’s (2003) evidence on electoral rules and corruption. Also, let's consider universal public good G as Presson and Tabellini’s SSW (social security and welfare spending). SSW is predicted to be lower with the MAJ system, which is consistent with the study's empirical findings. This is stretching the model a little too far. Still, in their literature on Political Economics, P&T show that if G is replaced with an explicit model of the demand for unemployment insurance, the same conclusions persist. (Ben Lockwood, 2015)

References:

Bawn, K. 2012. A Theory of Political Parties: Groups, Policy Demands and Nominations in American Politics. Available from:<http://www.vanderbilt.edu/csdi/TheoryofParty.pdf/>. Accessed [25 November 2015]

Besley, T.- Case, A. (1995): Does electoral accountability affect economic policy choices? Evidence from gubernatorial term limits, Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics, 110, 769-798.

Besley, T.- Coate, S. (1997): An economic model of representative democracy, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 85-114.

Bill, Stephen, Hindmoor, Andrew and Mols, Frank (2010) Persuasion as governance: A state-centric relational perspective. Public Administration, 88 (3): 851-870.

Democracy Building, (2014). Elections Voting Systems, Democracy Building 2004. Available from: <http://www.democracy-building.info/voting-systems.html/>. Accessed [25 November 2015].

Downs, Anthony. 1993. "The Origins of An Economic Theory of Democracy." In Bernard Grofman, ed., Information, Participation, and Choice: An Economic Theory of Democracy in Perspective. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 197-200.

Harrington, J.E. (1993): Economic Policy, economic performance, and elections, American Economic Review, 83, 27-42.

Hindmoor, Andrew (2005) Reading downs: New Labour and an economic theory of democracy. British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 7 (3): 402-417.

Median Voter Theorem, G-static 2015. Available from:<https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTdKnnRJs5uu4_0tRzzxJYGF7IASY4qfVkhmDSwcS0EEEUzIZ0SJ56WVGSD/>. Accessed [25 November 2015

Larcinese, Valentino. (2015). Models of Electoral Competition: EC260 The Political Economy of Public Policy. Available from:<https://www.google.com.pk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://personal.lse.ac.uk/LARCINES/Summer_Sch/election_models.PDF/>. Accessed [25 November 2015].

Persson, T.- Tabellini, G. (1998): The size and scope of government: comparative politics with rational politicians, mimeo.

Persson, T.- Tabellini, G. (2003): The Economic Effects of Constitutions. MIT PRESS, Cambridge.

Plott, C.R. (1967): A notion of equilibrium and its possibility under majority

rule, American Economic Review, 57 (4), 787-806.

Riker, W. H.- Hordeshook, P. (1968): A theory of the calculus of voting, American Political Science Review, 62 (1), 25-43.

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?