Important Recent Developments in Power Train Designs

February 27, 2021

Project Report

February 27, 2021The term ‘green infrastructure’ can mean different things depending on the context in which it is used; it may refer to trees and vegetation that provide ecological benefits in urban areas e.g. Hyde park or refer to engineered structures e.g. green roofs designed to be environmental friendly. According to American Rivers, “Green infrastructure incorporates both the natural environment and engineered systems to provide clean water, conserve ecosystem values and functions, and provide a wide array of benefits to people and wildlife”.

Green Infrastructure is a concept which highlights the importance of a strategically planned and managed network of natural lands, working landscapes, and other open spaces that conserve ecosystem values and functions and provides associated benefits to human populations (Benedict & McMahon, 2006). Green infrastructure is a network of multi-functional green space, urban and rural, which is capable of delivering a wide range of environmental and quality of life benefits for local communities. Green Infrastructure includes parks, open spaces, playing fields, woodlands, open fields, grasslands, green roofs, porous/permeable pavements and green walls, etc.

This project is intended to explore the understanding of green infrastructure can be of benefit to developing countries such as Nigeria. In doing so this work will highlight the social, economic and environmental benefits of green infrastructure close to where people live and work if applied. This can be done by following the right polices and strategies, using developed countries such as the United Kingdom, Singapore and the United States of America as examples. Also, this project will be looking at the environmental benefits of green buildings, indoor planting, and ways of saving energy.

Green infrastructure can be used to contribute to the aims and objectives of several different national and regional strategies of developing countries to improve the environment such as (Forest Research, 2010):

- To provide a space and habitat for wildlife with access to nature for people.

- Climate change adaptation – The implementation of sustainable urban drainage systems to reduce flood risk.

- To reduce ambient heat and flooding in urban areas due to the cooling effects of trees.

- Local food production - in allotments, gardens and through agriculture.

- Improved health and well-being- improving air and water quality.

- Improved health and well-being –providing opportunities for the local community to exercise and carry out other physical/recreational activities.

Also, the green building brings together a vast array of practices, techniques and skills to reduce and eliminate the impacts of buildings on the environment and human health such as

- Providing insulation and helping to lower urban air temperatures and mitigate the heat island effect

- Green roofs – Absorbing rainwater and reducing water waste.

- Green roofs–Reduce the building's average temperatures during hot temperatures in an arid area.

- Reducing the effect of stormwater flow and erosion control.

- Green walls – vegetation cover can provide cooling in arid areas.

- Planting of trees and vegetation to prevent erosion.

About the future of green infrastructure, Mell (2010) states that:

“The rate of urban and urban-fringe reconstruction will potentially continue exponentially over the coming century. As a result, the rate of development and re-development will also rise. It has been argued that it is difficult to recover green infrastructure once it is developed. However, during this period of reconstruction planners, developers and landscape architects could be presented with a platform for integrating a greater proportion of multi-functional green spaces in developments that meet ecological, economic and social needs found in green infrastructure principles.”

Research Objectives

The Objective of this research and as follows;

- Identifying the areas that lack or require green infrastructure.

- Identifying ways how GI can be used to reduce and save energy.

- Identifying ways of incorporating green walls and green roofs into structural designs

- Identifying ways how GI can be used in managing water resources to prevent erosion.

- Identifying ways of managing and reducing high temperatures in urban areas.

- Analysing and comparing past projects that made use of Green infrastructure and finding out how it can be of benefit used to different countries.

Research questions

This project addresses the following questions:

- What is green infrastructure? Where can it be found?

- Why is it important? How to use it?

- Why do we need to plan and protect green Infrastructure?

- What are the environmental benefits of green building? How to integrate plants into a design can reduce energy use?

- What are urban heat Islands and their effects?

- The use of Sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS)?

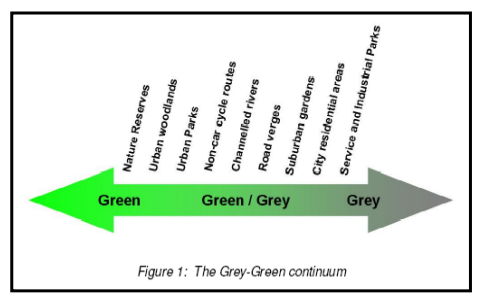

Furthermore, this study intends to find the balance and resolution of grey V green infrastructure in urban planning and development and investigation of micro aspects e.g. the planning and integration of trees and landscaping along with highways to provide flood protection and cut carbon emissions. How can GI be implemented, monitored and controlled? These are some of the questions that will form the body of this thesis and also provide an insight into how different user groups, academics and practitioners address and have used green infrastructure to the benefit of their community.

Chapter – 2; Literature review

The research conducted by various organizational groups and researchers will be presented in this section. The green infrastructure development in the UK, Europe and developing countries will outline, with special consideration to sustainability issues. Other important factors such as basic green infrastructure principles, fragmentation, landscape impacts, biodiversity of the subject technology, impact of multi-functionality, integration and interactions of policies, diversifications, resources important befits, environmental perceptions and special planning are presented in this section.

Green Infrastructure – Should it be termed green?

Although there has been significant development in the research for green infrastructure, questions are still asked about what green infrastructure actually is (MacFarlane, Davies and Roe, 2005)? Some authors claim that the concept is simply a redevelopment of old and existing technologies relative to green space planning. Some authors have even questioned the validity of the term Green Infrastructure as both these terms are known to have contrasting meanings. In the UK, however, the term is referred to landscape development projects that ensure sustainability along with a good physical environment.

Figure 2.1: The Grey-Green continuum (Davies et al., 2006)

Definition of Green Infrastructure

There are several definitions for Green infrastructure mainly because of the type of organizations and authors directly share a relationship with the idea of green construction (Ahern, 1995; Fábos, 1995). It should be noted that the definition used by conservationists is considerably different to the ones used by planners, infrastructure specialists and implementers (Benedict and McMahon, 2006). Although there are variations in terms of the definition of the concept, there are some common themes which are integral parts of all those definitions. The most comprehensive definition of green infrastructure as provided by Countryside Agency (2006) is given below:

“Green infrastructure comprises the provision of planned networks of linked multifunctional green spaces that contribute to protecting natural habitats and biodiversity, enable response to climate change and other biosphere changes, enable more sustainable and healthy lifestyles, enhance urban liveability and wellbeing, improve the accessibility of key recreational and green assets, support the urban and rural economy and assist in the better long-term planning and management of green spaces and corridors.”

Green Infrastructure Typologies

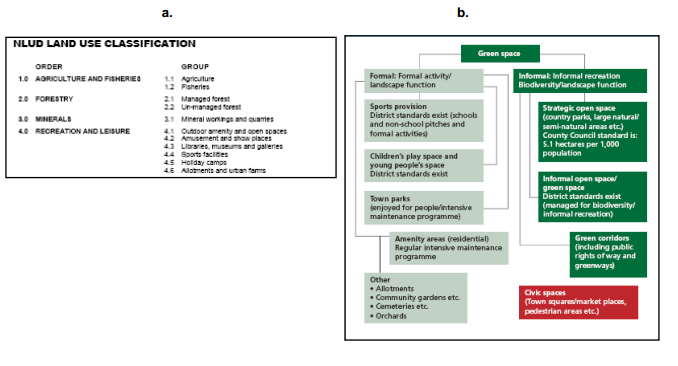

Space combination studies are vital within the studies on planning practices for green spaces. Green infrastructure typology was formulated by Davis et al, 2006, using the participation of the stakeholders and is a mirror of the classification system developed by Ahern regarding Greenways. The system is comprised of diverse landscape classifications and features proposing a green value. Ahern used planning strategy, landscape context, goals and scale as a basis of typology infrastructure classifications (Ahern, 1995).

The use of typology classification by Ahern highlights the limitations of such categorization. An example is a cemetery, a landscape element, which may constitute a place for spiritual residue but is located in a landscape which has high ecological value. Therefore, it is imperative to note the variations between land use and the classification of land to efficiently develop green infrastructure.

Royal Commission for Environmental Pollution, 2007, has furthermore developed a green infrastructure typology which categories green infrastructure into broad categories of public space, private space, sports grounds, informal, formal, strategic spaces and green corridors. There is a favourable comparison between this typology and that constituted by Davis et al. The classification by Royal Commission for Environmental Pollution is also in line with the categorization by National Land Use Classification systems. All these frameworks provide a specific element framework which helps in defining the elements of green infrastructure.

Figure 2.2 NLUD (a) and RCPE (b) land use and green space classifications

(Source: www.nlud.org.uk)

Without specific constituents of green infrastructure, the debate on the semantics and values of the concept is useless. The typology needs to be discussed in amalgamation with literature that uses a conceptual baseline for assessing the management practices of landscape, which includes looking into social, ecological and political influences on the development. This examination allows the assessment of connective multi-functional principles of the typology infrastructure.

Ahern, 1995, used three main classifications, namely, landscape functionality, spatial context and scale, which are inherent to the debate on green infrastructure and the assessment of the criteria for a wider benefit of ecology. Using the Ahern classification as a basis for research, the current studies classify the same elements as inherent. Benedict, 2006, TCPA, 2004 and TEP, 2005, all propose a typology based on a function-based approach whereas England RSS propose a spatial approach to the green infrastructure typology, which goes to suggest the overlap within the distinction of elements for the typology (Davies et al, Roe, 2004). Furthermore, it is pointed out by Owen and Kambites, 2007 that the integration of environmental, social and political policy in infrastructure planning invariably leads to its success. The typology proposed in the aforementioned essay highlights the amalgamation of green infrastructure with context, form and function along with social, ecological and economic review criteria.

The typology proposed shows a distinct similarity between the model used by Ahern and highlights the role played by space in the lives of people. The form used is prevalent in both the physical characteristics and the resources used in the space, but the distinction lies in the use of context as a source of classification through the use of cultural, economic, ecological and social influences on the landscape. This inherently allows the use of typology as a holistic view so it can encompass both the wider and the individual landscape.

Ahern, 2007, further points out that the infrastructure classification success lies with the supporters who are based on the notion of constant change in the existing infrastructure and the support for sustainable development which allows green infrastructure (Nelson, 2004).

The green infrastructure is a diverse set of elements which allows it to encompass various planning scenarios and a range of research studies. This flexibility allows the concept to be studied by various users and researchers who can incorporate it within their work. Given the diversity in the form, these ranges of elements of the landscape can be used and analysed as multi-faceted green infrastructure.

The historical development of green infrastructure

The aforementioned paragraphs have defined the typologies of green infrastructure, and the following paragraphs illustrate the historical development of the same specifically in Northern America and the United Kingdom in order to contextualize the literature provided by Howards, Greenways and Olmsted. The objective highlighted throughout the following section is to illustrate the development of green infrastructure through the influence of these particular programs in focused research and infrastructure planning.

Green Infrastructure Development in the UK, Europe and North America

Throughout the three countries, the United Kingdom, Europe and North America, the application of green infrastructure typology have varied substantially, which accounted for the difference in the planning strategies applied in each of the countries. Howard 1985, states that within the United Kingdom, the green infrastructure development has been primarily through the designation of either the protected area or through the notion of garden cities. OPDM, 2005, states that the notion of garden cities presented by Howard has been implemented within the nation's agendas in the form of urban renaissance and Thames gateway. Cervero, 1995, states that the vision promulgated by Howard includes an amalgamation of nature with the city by ensuring the sustainable promotion of living spaces by making urban areas into functional spaces. In contrast, within Europe, the development of green spaces has been integrated within the landscapes having a higher density to ensure the promulgation of urban green development schemes (Beatley, 2000; 2009).

In contrast to both Europe and the United Kingdom, green development within Northern America has been ensured through the conservation of landscape (Bendict and McMohan, 2006). The main difference that lies between the three green development infrastructure plans is in the proposed holistic approach to the development of green spaces. A comparison of the three systems illustrates that the North American system places importance on ecological benefits rather than economic or social benefits of green infrastructure development. The Environment Protection Agency

people have now begun to rectify this in the form of a conservation fund through recognizing the social value of the concept. The concept enunciated within the three aforementioned systems has been linked through research with various planning initiatives which include community forestry, urban renaissance, sustainable communities and smart growth. All these agendas and initiatives have been developed to ensure a functional landscape which takes into account the social, ecological and economic development of the said green infrastructure.

Sustainable communities

The Government of the United Kingdom, 2006, has defined sustainable communities to be places where people want to work and live not only in the present but also in the future. Hiding and Teunissen, 2002, state that because of the large number of people migrating towards the urbanised areas of the United Kingdom, there has been a large pressure on landscape development, and now it is being observed that this pressure has also shifted to the urban fringe where the availability for land development has lessened in terms of both industrial and residential polycentric network (Davis, 2006). The reason accounted for the increase in urban sprawl is the development of the communication and transport system which inherently allows people to commute over greater distances.

There has been a trend of people migrating towards urban areas in the United Kingdom, and also in many other urbanised nations. This has led to increased pressure on the landscape development process. This pressure is also building up at the urban fringe where there is a lack of land available for development due to the construction of residential and industrial infrastructure. The process has been named the global urban sprawl, which has been intensified by the advances in transport and communication infrastructure hence allowing people to travel across greater distances. As a result, there has been a greater demand for housing facilities, communication developments, transport, and other essential services. Thus, there is increased pressure on the land, especially the green and brownfield sites, to cope with the demands of this 'extra' population.

According to recent surveys by OPDM and DTLR, it has been suggested that the urban-based proportion of the nation’s population is now 80-90%. These statistics show a disproportional pressure on service as well as the green infrastructure in areas of growth. Also, traditional urban-rural problems have been pushed into the urban fringe. For a long time now, migrating to urban centres with the aim of gaining employment, housing, education, and health care has been associated with economic growth. It has been like this in the UK since the Industrial Revolution. However, it has been seen now that some people are moving away from urban centres to escape the population densities, pollution and stressful aspects of urban life. Thus, there has been a trend of moving away from urban centres in a portion of the urban population, which has raised questions regarding the quality and fragmentation of urban and urban fringe landscapes.

The aim of this literature is to investigate how the migration of people into and away from urban centres has affected both the physical and social landscape of the UK. Also, factors influencing community development have been discussed in order to make the places more sustainable.

“Sustainable communities” is an old idea in North America where it has been greatly promoted as Smart Growth. This idea suggests that we reinvest in existing landscapes and develop more efficient mixed-use communities. In the UK, the idea covers developing communities around integrated housing and commercial and essential infrastructure which can serve people belonging to different income groups.

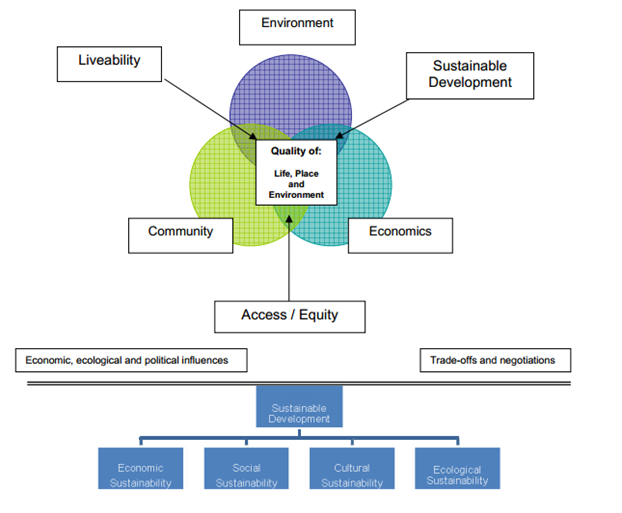

Figure 2.3: Components of what makes the quality of place system (based on Shafter et al., 2000)

To most effectively sustain the socio-economic health of an area, mixed-use landscape features and services can be connected. It is a good idea to keep in mind what the community needs the most before assessing how to best sustain that community in the long run.

The Sustainable Communities Plan is different from the traditional development plans because it acknowledges the fact that the community needs and the needs of the environment are equally important as economic influences. The combination of social, economic and environmental influences emphasizes the fact that each of the three has its role to play in the development of sustainable, equitable and liveable habitats. Meeting the needs of the existing as well as the future generations is a part of the plan, and so is the idea of the need to respect the lifestyle and needs of international or distant communities, hence creating more sustainable communities.

The benefits of green infrastructure

This section discusses how green infrastructure can help in carrying out many alternative functions and also suggests the areas where there is a need for further research regarding green infrastructure.

Health

Research has revealed that the greater the proportion of green space in the environment a person lives in, the more positive its effect on the perceived health of that person. Green space is enormously effective in relieving stress and fatigue. Ulrich (1984) showed in his research that the ability to move within or even view green space aided to reduce the recovery times of patients compared to those to whom green space was not available. People moving into green areas generally start considering themselves to be healthier than before.

Increased awareness about the benefits of green space on health has led to a drastic increase in the average number of visits a year to the countryside and seaside by the public. Since this shows that the mindset of the people has changed, it should be followed by the idea that green space should be the central element of urban and urban-fringe planning.

Exercise, recreation and leisure

Exercise is considered one of the main benefits that green infrastructures provide. The green spaces can be of various sizes depending on the location. But recently it has been seen that local authorities have been selling these green spaces like playing fields for financial and social reasons. The solution to this lies in green infrastructure planning, which provides green spaces of various forms and sizes which can be retrofitted into the already designed landscapes that currently exist.

The general population can be actively engaged with their environment using recreation in the green spaces. This requires good planning, but its benefits are manifold. The UK government promotes social interaction and exercise as vitals in the development of sustainable communities. Both of these can be achieved through well-planned recreational opportunities for the people in the green spaces. The Nature-Deficit Disorder (NDD) covers physical and psychological impairments which can lead to a lack of interest in outdoor environments and landscapes. NDD can be effectively countered using appropriate and innovatively designed recreational activities in green spaces. Thus, by helping rebuild the relationship between the community and their landscape, the effects of NDD can be minimized.

Education

The space a child plays in is of equal importance to its learning as the space in which it lives. The nature of the neighbourhood is one of the most important factors in the social and cultural development of children. Also, it has been found that when children are placed in a natural environment instead of a traditional classroom, they tend to learn a lot through exploration, interaction, reflection, construction, and understanding. This is known as discovery learning. Hence, discovery learning has been proven to be critical to better learning along with traditional classrooms.

This suggests that the landscape should be designed to provide a healthy green space for discovery and learning by the new generation. This is facilitated by green infrastructure, which will not only solve the current problem of lack of interaction between children and their environment but will also help in the long-term improvement of the relationship between the people and the landscape.

Regeneration and economic growth

Green infrastructures are known to provide high-quality environments. These can encourage investment, both economic and physical. In areas of economic decline, special importance is given to investment in landscapes. An example is that of the Durham Coalfield, which was once an industrial centre. Alternatively, green infrastructure can provide a new focus for employment or economic development.

Accessibility and social connectivity

Groome (1990) has stated that the physical environment can be enhanced by linking places, which also provides people with the ability to access alternative environments and thereby exchange cultures. Green infrastructure promotion is primarily motivated by the benefits of linking people. More opportunities are available for use by connecting people through a wider network of spaces. Moreover, this can aid other agendas like health and education.

Hence, green infrastructure holds many benefits which can be viewed in different aspects of daily life. Through the promotion of the ideas of multi-functionality, connectivity among people and strategic planning, green infrastructure can be seen to solve many issues being faced by the masses nowadays as well as improve the quality of life.

Spatial planning

Practitioners and planners who are going to attempt to develop green infrastructure, have been provided with a cautionary note by Davies et al. (2006), in which they write that professionals aiming to successfully develop green infrastructure must:

- know the basic concepts of environmental systems

- know the basics of multi-functionality

- have an understanding of how economic, environmental and social issues intermingle when developing sustainable communities and related agendas.

It must be clear from the above-given points that an understanding of all overarching influences is critical to the development of a space into a high-quality environment. Consequently, the planning policy should be such that it provides a framework where developers and planners can communicate as well as use the available knowledge and expertise. It is because of this importance, that an essential component for green infrastructure development in the UK is the planning system. This provides criteria for its integration into planning and policy. The National Audit Office and ODPM both have stated that planners need to make sure that the development of high-quality green space is in line with the statutory planning regulations.

To deliver green infrastructures at various scales, different areas of planning policy and practice can be put to work. This will be discussed in the following section.

We see from the review of Kambites and Owen (2007), we see the differences between green infrastructure planning and green infrastructure thinking. There is a need to develop a framework to allow the translation of achievable targets from green infrastructure thinking. Grounded guidelines for this framework are yet to be produced, but agencies like CABE Space and Natural England are currently working on it.

Several areas of spatial planning policy and practice have been included in the following chapter. These are in reference to the policies and practices in the UK.

Green infrastructure and the British planning system

Green infrastructure has enabled various ways to achieve planning and development goals. This has been done through the provision of multiple benefits for diverse user groups. There is a need to discuss the green infrastructure concept within a policy context. The policy must be such that green infrastructure planning should be given importance equal to other infrastructure planning. Doing this will ensure long-term sustainable planning.

According to Benedict and McMahon (2006) and Randrup (2006), in order to develop better living places, there is a need for a greater level of cooperative planning at different planning scales. The scale can be national, regional or even local.

The subsequent section describes how the planning of green infrastructure in the UK is incorporating the research of Benedict and McMahon.

Green space planning in the UK

As forerunners to the Sustainable Communities Plan of the UK Government, the Urban White Paper and the Rural White Paper, contain an outline of the agenda to develop better places set by the UK Government. The main theme was the creation of communities which were to be built upon innovatively designed public spaces. As a result of these reports, an ‘Urban Renaissance’ was achieved along with improved countryside. A more holistic approach to planning was adopted, which not only took into account the value of both grey and green infrastructures but also considered the social, economic and environmental agendas. This approach resulted in better-designed green infrastructures.

Hence we can see that the planning policy holds special importance in the process of delivering better places. This is done through the provision of a framework and the regulations adhered to by the planners.

Chapter 3: Green Infrastructure and the environment

There are several economic and environmental benefits associated with Green Infrastructure. However, it should be noted that these benefits mainly highlight urban and semi-urban areas where damage to the environment can be significant along with insufficient green space.

Reduced and Delayed Stormwater Runoff Volumes

The concept of green infrastructure utilises absorption capabilities of soils and vegetation as well as natural retention to reduce peak flows and storm water run-off volumes. The stormwater inflation rates can be increased substantially by simply enhancing the quantity of the previous ground cover. This further ensures that less volume of run-off enters separate or combined sewer systems including streams, lakes and rivers (Jongma et.al, 2004).

Enhanced Groundwater Recharge

The rate at which ground waters aquifers are recharged can be increased greatly, thanks to the infiltration capacities of green infrastructure and construction systems. This is a striking argument considering groundwater accounts for nearly forty percent of the water required to maintain the average flow of our lakes and rivers. The improved groundwater system can also improve the supply of drinking water to the public and private sectors in a country (Kiel et. al, 2003; 1998).

Stormwater Pollutant Reductions

Green Infrastructure helps prevent pollutants from entering nearby surface waters mainly by infiltrating runoffs close to the source. The microbes and plants can clean and break down a range of pollutants from stormwater as the run-off infiltrates into the soil.

Increased Carbon Sequestration

Carbon capture and removal from the atmosphere through the photosynthesis process, also known as the phenomenon of Carbon Sequestration, is a blessing to soils and plants that form the green infrastructure.

Urban Heat Island Mitigation and Reduced Energy Demands

Green infrastructure is also known to improve the quality of air by increasing the number of trees and vegetation in urban areas. A large number of pollutants including carbon dioxide are directly consumed by these trees and vegetation through contact removal and leaf uptake (Kiel et.al, 2003; 1998). Furthermore, when planted according to the plan these trees and vegetation can reduce the temperature of the air quite substantially. Human health, in general, can also improve from trees and vegetation and this argument has been proved true by several studies. According to research performed in the United States, reduced levels of violence and inner city crime have been observed in places with green space, plants and trees in addition to better academic performance (Mell, 2007).

An increase in wildlife habitat and recreational activities has also been observed under green infrastructure that supports urban forests, vegetated swales, greenways, wetlands and parks.

As the natural land cover is replaced by dense concentrations of buildings, pavements and other heat-absorbing surfaces in the cities, the urban heat islands continue to form and therefore the cooling effects of trees and vegetation are considerably reduced. Furthermore, tall buildings, factories, and narrow streets trap and concentrate waste heat from factories and buildings also play their part in increasing the temperature of the air. Green infrastructure can therefore provide valuable and much-needed cooling to tackle the effects of urban heat islands by reducing the overall energy requirements. It should be noted that green roofs and green walls and other similar green infrastructure can play a key role in reducing the energy demand of a society, which in turn lowers the emissions from energy sites (Pepper, 1996).

Increased land prices

Property values of surrounding areas are also increased greatly, various studies have confirmed. A programme that converted abandoned lots into a green and clean society that caused that resulted in improved land value. An increase of as much as 30 percent in the housing values in the surrounding areas was observed, thanks to the green retrofit programme that provided at least a $4 million gain for the investors.

Green Roofs

The idea of green roofs is simple but interesting. A vegetated landscape is prepared from a series of layers that are placed on the surface of the roof as modular blocks or loose-laid sheets. There are several reasons why engineers may decide to install green roofs.

A green roof may be used as a space for people to visit, as a sign of architectural beauty, to enhance the value of the property and gain certain environmental benefits including thermal insulations, stormwater handling and biodiversity. Vegetation on the roof is achieved by using a soil-like substance also known as growing substrate. The depth of this medium is usually 50mm or more and mainly depends on the design and capacity of the roof of the building. Most green roofs work best with irrigation although it is possible to create green roofs that work without irrigation (Ahern, 2007; Carter and Fowler, 2008).

Green roofs can be either intensive or extensive. Intensive green roofs are bigger and heavier compared to their counterparts. A deep layer of substrate that supports a range of plants is what adds to the weight of the roof. Extensive roofs, on the other hand, are smaller in size and lightweight because they have a very thin layer of substrate to support growing plants.

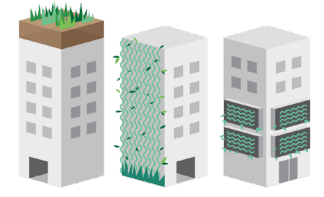

Figure 3.1: Green Roofs of Green Infrastructure

Green Walls

Green walls, as the term suggests, are walls of plants and vegetation grown vertically and attached to external or internal walls. The entire support structure is planted for a green wall. The irrigation and drainage system, vegetation and the growing medium are all incorporated into one system for a green wall. There are several benefits that can be obtained from a green wall system including attractiveness of the building, improved air quality, sustainability of vegetation and greenery and cooler microclimates.

Figure 3.2: Green Walls of Green Infrastructure

One of the key benefits of green walls and green roofs is the fact that the residents of the building are bound to experience reduced heating and cooling costs. In summers, green walls act as a key source of cooling, proving shelter and shading for people. The heat transfer in summer through walls and roofs can also be controlled significantly with the help of this valuable technology. The following are the factors that must be taken into account by designers to ensure energy savings as well as lower temperatures (Jim and Chen, 2003).

- The depth of soil substrate and type of vegetation used

- Roof to wall ratio

- Climatic conditions and microclimate of the building

- The thickness of insulation

- The area of the roof covered by vegetation

- The height of the building (upper floors are expected to benefit more)

- Improved efficiency of HVAC System

Much research has been completed in an effort to determine the best depth of soil substrate and type of vegetation for green walls but it should be noted that designers take several factors into account to reach the optimum value.

Green Infrastructure and sustainable urban development

In this section we will be discussing the green infrastructure as a component of sustainable urban development will be considered as the area of primary research. The application of green infrastructure in an urban area requires several factors such as transportation and road networks, economic development, high-density landscapes and population to be considered as a whole. Green infrastructure brings a lot to the table in this regard as it offers size, function and form of the landscape that can solve various issues such as space, capacity and supply (Beatley, 2000; 2009). Therefore several sustainable communities as well as world-class places have implemented the idea of green infrastructure and benefited greatly from its principles. The social needs of members of the society in an urban area can be met in long term by providing access to high-quality spaces as well as ensuring multi-functional spaces.

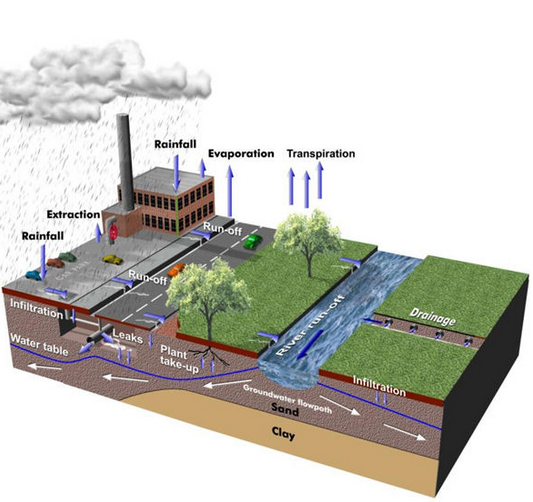

Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS)

The importance of green infrastructure in terms of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems is quite significant. The purpose of sustainable urban drainage systems is to somewhat form a balanced relationship between natural landscapes and human activities. Several ecosystem services that support improved irrigation, reduced pollutants, controlled runoff events and soil management can be achieved by implementing SUDs in the form of tricky techniques such as permeable pavements, habitat banking and bioswales (Ferguson, 2002; Kloss and Calarusse, 2006).

The effects of changing environment can be controlled to a certain extent with the help of ecological function provided by each of these techniques. Furthermore, compared to the typical structural building works, the cost of these intrusive processes of engineering is considerably less. By storing grey water and water from the rainfall for recycling, the SUDS can provide a valuable tool to control the additional resources needed for urban development to thrive. Much of the potable water, therefore, can be recycled as the pollutants and wastes are removed by the tiered drainage system and bioswales. However, it should be highlighted here that the use of SUDs technology in urban regions is very limited due to the lack of space and the land area required for setting up a SUD. Some researchers insist that SUDs can be incorporated into the design of existing infrastructure, thereby preventing additional costs and land takes. The water basin, which is a part of a SUD design, provides storage for the water and reduces the flood risk considerably.

Figure: 3.3 Sustainable Urban Drainage System (SUD) – Source: http://www.bgs.ac.uk/suds

Chapter – 4; Methodology

A multi-method data collection approach is being used to complete this chapter. Primary and secondary data were collected using various databases including the university library and online databases such as science direct. Case studies and practical implementation of green technology will be completed, and arguments will be presented in the form of discussion with respect to real-world applications. Spatial focus and justification for each review will also be presented.

A multi-method approach to data collection

As briefly highlighted above, a multi-method approach was adopted to complete the data collection process. The factors behind the completion of this methodology are briefly discussed under this heading. The mix of reference resources for the purpose of data collection allowed for reliable analysis and recommendations to be made. The purpose of this section in this report is to present the argument that the use of the multi-method in place of primary and secondary data collection methods provided a better understanding of the concept, the legal complications as well as applications, benefits and implications. It should be noted that a large effort has been made to focus on qualitative analysis to reach a greater understanding of the findings and results. The quantitative data is also used after conducting qualitative studies of green infrastructure including descriptions and discussions directly related to the development of green infrastructure.

The multi-method for data collection provided a range of options and therefore every aspect of the investigation was evaluated separately and then as a combination. Eventually, the methodology allowed for more reliable discussions, which are presented in the Results & Discussion section. In summary, the use of a multi-method for data collection improves the efficiency of the findings and results by obtaining information from several sources (Greene and Caracelli, 2003; Denzin, 1978). To be able to achieve a greater level of understanding and knowledge, the use of multiple reference resources was considered to be ideal as this technique bridges the gap between secondary and primary data collection resources. Furthermore, this valuable methodology helped in underlying principles and definitions of green infrastructure, its development and landscape that could be used by researchers and explorers in the future.

Documentary Analysis

It should be noted that documentary analysis was used as an important source of investigation when collecting valuable information directly related to the concept of green infrastructure. Ideas, information, themes and principles highlighted and outlined in various policy and practitioner documents were thoroughly reviewed. This helped in achieving a deeper understanding of how the principles relative to the topic are generally practised and implemented by key decision-makers and policymakers.

Academics, practitioners and groups with an interest

However, various academic sources such as books, journals, articles, papers, reports etc were used as the primary source of information when writing this dissertation. As discussed before, the authors of these academic articles presented arguments differently and the next chapter aims to discuss those arguments to come to concrete results. Furthermore, practitioners and groups sharing an interest in the concept and green infrastructure and its implications were also engaged as part of the data collection process in order to complete this dissertation. The academics and groups with interest were directly or indirectly involved in the evaluation of the idea of green infrastructure, planning and implications.

Chapter – 5; Discussion

This chapter introduces the results, discussion and analyses through the attainment of key information from the previous chapters. Qualitative and some parts of quantitative data are analyzed in this section. Based on the arguments presented, the future of green technology is assessed, and the subject technology policies/practices, planning and environmental impacts for the next few decades are evaluated and presented.

Looking at the definition from various authors, it will be fair to say that the definition of green infrastructure remains a bit unclear mainly because of the diversity in the focus of those researchers. It should be noted that only one definition of green infrastructure has been mentioned in this dissertation for the purpose of better understanding. The availability of numerous definitions shows the concept's diverse applications in terms of practical use. The UK's response to the green infrastructure differs considerably from the responses of Europe and North America. In the UK, the focus of researchers has remained on the economic, ecological and planning policy benefits of the concept. Concluding, the UK is determined to play its parts in the development of landscapes that meet sustainability targets such as human activities and lifestyle improvement, economy and ecological functions by initiating policy and planning coordination at the highest level.

The literature review chapter briefly discusses the elements that constitute green and grey landscapes and are briefly discussed here. Researchers consider the concept of green infrastructure as a green agenda or idea. From the research, it was concluded that the basic elements of green infrastructure mainly depend on conceptual and physical terms as well as landscape functionality. Since there are various connective elements of primary importance to the idea of GI, there can be different functions and forms of landscape. Just like the differences in opinions regarding the definition of GI, there are different opinions about the elements that constitute a green infrastructure. However, there is a clear vision among the researcher about how this technology will evolve shortly.

Green infrastructure is expected to become an influential engineering technology in an urban areas where there is insufficient space for further land development. There are a number of benefits that could be associated with the concept of GI but some of them were discussed in the literature review chapter. The green walls and green roofs are designed to consume pollutants such as carbon dioxide and the process eventually results in a better environment for human beings, thus improving the health of each individual. Green infrastructure supports exercise, recreation, leisure as well as education and further ensures economic growth of the landscapes.

Numerous environmental benefits can be associated with GI. The concept of green infrastructure utilises absorption capabilities of soils and vegetation as well as natural retention to reduce peak flows and storm water run-off volumes. The rate at which ground waters aquifers are recharged can be increased greatly, thanks to the infiltration capacities of green infrastructure and construction systems. Green Infrastructure helps prevent pollutants from entering nearby surface waters mainly by infiltrating runoffs close to the source. Green infrastructure is also known to improve the quality of air by increasing the number of trees and vegetation in urban areas. As plants and trees absorb pollutants such as carbon dioxide, the quality of air for living beings improves gradually. Hence, it will not be wrong to say that by supporting the n infrastructure technology, the living environment of the earth can be improved for in days to come. An increase in wildlife habitat and recreational activities has also been observed under green infrastructure that supports urban forests, vegetated swales, greenways, wetlands and parks. Wildlife habitat is known to thrive in environments that are rich in vegetation. Green infrastructure technology is designed to increase the quantity of vegetation and trees for wildlife to grow consistently. Another notable benefit of green infrastructure is the increase in the property/land prices of the surrounding areas. As human beings, we all want to live in a space that is close to nature. The attractive surroundings of green landscape attracts new buyers and investors and the process of price increase eventually results in considerable financial benefits for the residents as well as the investors.

Reduced and Delayed Stormwater Runoff Volumes, Enhanced Groundwater Recharge, Stormwater Pollutant Reductions, Increased Carbon Sequestration, Urban Heat Island Mitigation and Reduced Energy Demands, increase in wildlife habitat and recreational activities, Increased land prices, green roofs, green walls, Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) are expected to become influential factors in making the concept of green infrastructure success in the future.

Conclusion:

As discussed in the previous chapters, research in the United States, Australia, and other parts of Europe has shown that the concept of green infrastructure could be extremely beneficial in the future if the planning is executed to perfection. The technique can result in successful landscape management and planning for the planners and implementers. Taking into account various aspects of green infrastructure technology, it is assumed that this conceptual thinking has a range of applications and in diverse conditions. A number of government-based organizations in the UK and USA have now started to promote the use of green infrastructure after recognizing the role of green infrastructure technology under the umbrella of the green space programme. However, it should be noted that the key decision makers and policymakers will be required to continue their support for this concept to gain worldwide acceptance. Furthermore, there is a need to acquire appropriate funding to help planners and designers dig deep to improve the efficiency of the process. A substantial increase in the land value in the UK, USA and Europe has been forecasted, thanks to the use of optimum economic designs for development. Therefore, it will be fair to say that green infrastructure has a key role to play in the future in terms of providing a valuable approach toward economically viable and sustainable land development (CABE Space, 2005).

As the concept of green space supports natural and ecological resources and the efficiency of landscapes and buildings whilst keeping the cost of construction at acceptable levels, it has gained immense popularity in certain urban regions in the UK, USA, North America and Europe. The popularity is expected to grow considerably in the future as more and more such projects are completed successfully. Dunn and Stoner (2007) claim that the maintenance cost of green infrastructure compared to other similar projects is quite low in addition to the low revenue/budget requirements. Using connective green infrastructures, developers can now focus on building effectively within smaller spaces rather than requiring large pieces of land (Countryside Agency, 2006; Ahern, 2007).

References

- Antrop, M (2000) Background concepts for integrated landscape analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Vol. 77, No. 1. Pg. 17-28.

- Ahern, J (1995) Greenways as a planning strategy. Landscape and Urban Planning. Vol. 33., No. 1-3.

- Pg 131-155.

- Ahern, J (2007) Green infrastructure for cities: The spatial dimension. In: Novotny, V & Brown, P (Eds.) (2007) Cities for the Future Towards Integrated Sustainable Water and Landscape management. IWA Publishing, London. Pg. 265-283.

- A & Teddlie, C (Eds.) (2003) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioural Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- American Rivers (2013). What is green infrastructure? Available at: http://www.americanrivers.org/initiatives/pollution/green-infrastructure/what-is-green-infrastructure/#sthash.L4L6aSER.dpuf [Online accessed on the 16th October].

- Banks, M (2001) Visual Methods in Social Research. Sage, London.

- Beatley, T (2000) Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities. Island Press, Washington D.C

- Beatley, T (2009) Green Urbanism Down Under: Learning from Sustainable Communities in Australia. Island Press, Washington DC.

- Benedict, MA & McMahon, ED (2006) Green Infrastructure: linking landscapes and communities. Island Press, Washington.

- Blackman, D & Thackray, R (2007) The Green Infrastructure of Sustainable, Communities. England’s Community Forests. www.roomfordesign.co.uk, http://www.communityforest.org.uk/resources/ECF_GI_Report.pdf

- CABE Space (2003) Planning green infrastructure. CABE Space, London.

- CABE Space (2005a) Start with the park: Creating sustainable urban green spaces in areas of housing growth and renewal. CABS Space, London.

- CABE Space (2005b) What are we scared of? The value of risk in designing public space. CABE Space, London.

- CABE Space (2005c) Decent Parks? Decent Behaviour? The link between the quality of parks and user behaviour. The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, London

- CABE Space (2006) Does Money Grow on Trees?. CABE Space, London

- Cervero, R (1995) Planned Communities, Self-containment and Commuting: A Cross-national Urban Studies. Vol. 32, No. 7. Pg. 1135-1161.

- Davies, C, McGloin, C, MacFarlane, R & Roe, M (2006) Green Infrastructure Planning Guide Project: Final Report. NECF, Annfield Plain.

- Denzin, NK & Lincoln, YS (2000) Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research. In: Denzin, NK & Lincoln, YS (Eds. (2000) Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edition. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Denzin, NK (1978) The logic of naturalistic inquiry. In: Denzin, NK (Ed.) (1978) Sociological methods: A sourcebook. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Environment Agency and Countryside Agency (2005) Green Infrastructure and Sustainable Communities. Environment Agency and Countryside Agency, Nottingham.

- Ferguson, BK (2002) Stormwater Management and Stormwater Restoration. In France, RL (Ed.) (2002) Handbook of Water Sensitive Planning and Design. Lewis Publishing, New York. Pg.11-29.

- Forest Research (2010). Benefits of green infrastructure. Available at: http://www.forestry.gov.uk/pdf/urgp_benefits_of_green_infrastructure.pdf/$file/urgp_benefits_of_green_infrastructure.pdf [Online accessed on the 9th October].

- Groome, D (1990) ‘Green Corridors’: a discussion of a planning concept. Landscape and Urban Planning. Vol. 19, No. 4. Pg. 383-387.

- Howard, E (1985) Garden Cities of To-morrow. Attic Books, Eastbourne

- Howard, P & Pinder, D (2003) Cultural heritage and sustainability in the coastal zone: experiences in south west England. Journal of Cultural Heritage. Vol. 4, No. 1. Pg. 57-68.

- JIM, CY & Chen, SS (2003) Comprehensive greenspace planning based on landscape ecology principles in compact Nanjing city, China. Landscape and Urban Planning. Vol. 65, No. 3. Pg. 95-116.

- Jongman, RHG, Kulvik, M & Kristiansen, I (2004) European ecological networks and greenways. Landscape and Urban Planning. Vol. 68, No. 2-3. Pg 305-319.

- Kambites, C & Owen, S (2007) Renewed prospects for green infrastructure planning in the UK. Planning Practice and Research. Vol. 21, No. 4. Pg. 483-496.

- C. Chiadikobi , A. O. Omoboriowo , O. I. Chiaghanam , A.O. Opatola and O. Oyebanji (2010).Flood Risk Assessment of Port Harcourt. Available at http://www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com/advances-in-applied-science/vol2-iss6/AASR-2011-2-6-287-298.pdf [Online accessed on the 29th October].

- Kiel, R (2003) Urban Political Ecology Urban Geography. No. 24, Vol. 8. Pg. 723-738.

- Kiel, R, Bell, DVJ, Penz, P & Fawcett, L (Eds.) (1998) Political Ecology: Global and Local. Routledge, London.

- Kieron Doick and Tony Hutchings (2013). Air temperature regulation by urban trees and green infrastructure. Available at: http://www.forestry.gov.uk/pdf/FCRN012.pdf/$FILE/FCRN012.pdf [Online accessed on the 9th October]

- Mark Benedict and Edward T. McMahon (2006). Green Infrastructure, Linking Landscapes and Communities. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-558-4.

- Mark A. Benedict and Edward T. McMahon (2001). Green Infrastructure: Smart Conservation for the 21st Century. Available at: http://www.sactree.org/assets/files/greenprint/toolkit/b/greenInfrastructure.pdf [Online accessed on the 5th October].

- MacFarlane, R, Davies, C & Roe, M (2005) Green Infrastructure and the City Regions. Discussion Paper. NECF, Dunston.

- MacFarlane, R & Roe, M (2004) Strategic Planning for the Development of the North East Community Forest: A GIS Study. North East Community Forests, Dunston.

- Mell, IC (2009) Can Green Infrastructure promote urban sustainability? Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Engineering Sustainability Vol. 162 March 2009, Issue ES.1.

- Mell, IC (2007b) Can Green Infrastructure promote the Urban Renaissance and aid urban sustainability in the UK? Proceedings - International Conference on Whole Life Urban Sustainability and its Assessment. Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow. Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow.

- Miller, RW (1997) Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Green Space, 2nd Edition. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

- Miruna Dudau (2011). Green Infrastructure -Sustainable Investments for the Benefit of Both People and Nature. Available at: http://www.surf-nature.eu/uploads/media/Thematic_Booklet_Green_Infrastructure.pdf [Online accessed on the 12th October]

- Natural England (2013). Natural England. Available at: http://www.naturalengland.org.uk/ourwork/planningdevelopment/greeninfrastructure/default.aspx [Online accessed on the 9th October].

- Pepper, D (1996) Modern Environmentalism: An Introduction. Routledge, London.

- Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (2007) The Urban Environment: Summary of the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution. RCEP, London.

- Ryan, RL, Fabos, JG & Allan, JJ (2006) Understanding opportunities and challenges for collaborative greenway planning in New England. Landscape and urban Planning. Vol. 76, No. 1-4. Pg. 172-191

- Wildlife Trusts (2012). Planning for a Healthy Environment –Good practice guidance for green infrastructure and biodiversity. Available at: http://www.wildlifetrusts.org/sites/default/files/Green-Infrastructure-Guide-TCPA-TheWildlifeTrusts.pdf [Online accessed on the 9th October].

- Williamson, KS (2003) Growing with Green Infrastructure. Heritage Conservancy, Doylestown, PA

Get 3+ Free Dissertation Topics within 24 hours?